In the Land of the Non-Buddhas

A story of disappearance in the Afghani mountains

Edoardo Albinati

From 7 April to 31 July 2002, Edoardo Albinati volunteered as a Community Services Officer in Kabul, Afghanistan, for the United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR). His responsibilities entailed providing assistance to the most bereft category of refugees, those identified as Extremely Vulnerable Individuals (EVI). In the extract from his diary reproduced below, Albinati is on his way to Bamiyan, the home of the Buddha statues destroyed by the Taliban regime in March 2001.[1]

Long stretches of desert but even there, out of nothing, an old man materializes walking down the road, or a soldier, his Kalashnikov decorated with fluorescent tape.

Hazara women with flame-red shawls bent over in the fields, pulling weeds. Their faces are uncovered.

It’s less of a problem here; the requirements of work come before everything else. Often a man comes up the path leading a donkey ridden by a woman, a Mongolian-eyed baby wrapped in her shawl, nursing. The shawl has fantastic tonalities of blue and red. The baby’s eyes are lined with kohl all the way to the temples.

With the chief of mission (an Italian), the obligatory iconographic references are: The Rest on the Flight into Egypt and Night Song of a Wandering Shepherd, when stark against the desolate land stands out the tiny figure of a nomad lying on the ground by his flock. But the most-cited character is Wile E. Coyote. No kidding! Many canyon peaks culminate with that type of flat rock or towering mass destined to crash down on his head as a result of his experiments with Acme products—the slings, the jet-propulsion rockets, the crossbows, glue, ostrich-feed, etc.

We are using a map drawn in pencil by our driver’s father; it’s more trustworthy and precise than the printed ones, and Waisuddin sprinkles it with facts about the locales we pass through. For example, the village of Chekali features the most beautiful girls in the province. All the Hazara bachelors come to Chekali to look for wives. For now all we see are little girls, truly stupendous, Mongol faces and gaudy little dresses.

We cross paths with a convoy coming back, amazingly beat-up tourist buses with German and English writing on the side: Modernreisenbus, Have a Nice Trip, Wellcome!

A half-hour before Bamiyan, we cross a valley with the most extraordinary collection of rocks of every imaginable color: ochre, grey, blacks dripping like ink from the peaks, slate blue, dusk, and pink, though the dominant is red, a red gorge and halfway up the mountainside a dead city, also red, with castles and dead towers, everything dead and eternal, and down at the bottom where the valley spreads out in the distance, the usual barrier of snowy peaks with sunlight sparkling off them. Everything here was destroyed by Genghis Khan 800 years ago. The inhabitants killed his favorite nephew during a siege—he took revenge by exterminating every living thing in the valley. Abrupt end to the millenarian civilization of Bamiyan. All that remained were the mute Buddhas 50 meters high. Until the Taliban used them for shooting practice (March 2001).

From far off, when I recognize the two huge empty niches, I hold my breath. From now on I’ll call them the non-Buddhas, because the negation of something still in a certain way affirms its presence. Those niches are not really “empty”; they have been “emptied” of something. I can’t resist an almost admiring comment on the fanatic gesture of the Islamic students. A destructive and perfect faith that doesn’t step back even before senselessness.

“What are you talking about?!” yells my chief, outraged. “It was just a scheme to blackmail the international community: the Buddhas used as hostages in negotiations to obtain political recognition for the Taliban government.”

The last stretch of the journey is of vertiginous beauty. I suddenly stop making comparisons. We are at the feet of the red rock wall where until last year there were two giant statues of Buddha. First they mined them with great care, then they amused themselves shooting rockets at them from below, and finally they blew them up. The UNHCR compound is up on a plateau; from its roof you can see (turning 360 degrees clockwise): the walls of the non-Buddhas; the old city—a small, conical mountain the color of yellow ash perforated with caverns and habitations—a dead, mined city; the brilliant pinnacles of the gorges we passed through to get here; then a stretch of bare hills behind whose silhouette are mountains crowned with dark clouds; and to the west a far distant saw-edged row of peaks on which the sun is setting. The wind is fluttering the blue UN flag against the dazzling white of the snow. From November to March this post is covered with snow. We are at 2,400 meters.

The stone wall that enclosed the gigantic Buddhas is punctured with hundreds, possibly thousands, of grottoes. It’s like an anthill. Families of IDPs (internally displaced persons) live there. The authorities want to drive them out, in theory to protect the archeological zone (let’s hope the insane idea of rebuilding the Buddhas doesn’t fly). They’ve been given an ultimatum to leave. Otherwise they will be evicted by force. We are trying to determine where these internal refugees come from, why they are there, and how we can help them. Once upon a time these caverns were inhabited by monks who built them before Buddhism was extirpated by Islamization, after which the holes were occupied for centuries by every sort of homeless unfortunate. In the Bamiyan area, successive waves of war and ethnic cleansing compelled practically every group to flee, return, flee again, and try to return again, in rotation—but, like neighbors of the opportunistic cuckoo bird, they often find their nests destroyed or occupied by others uninclined to clear out. We climb gasping up the limestone ledges to the mouth of the grottoes marked by recent human presence: walls blackened by smoke, fresh animal shit. No one seems to be around today; the little doors of the grottoes (minuscule, like in fables or Grimm tales) are barred shut, and it must be because of the gathering we notice a kilometer away, near the junction between the rock facades of the male Buddha and the female Buddha. Something is happening that has roused the cavern people from their warrens. Finally someone comes slogging up from below, and we follow behind him ascending. It turns out to be a little old man with a pair of bright, brand-new jogging shoes under his arm, together with his granddaughter, her eyes frighteningly blue. They graciously open their residence in the rock for us, a dark, low hole with irregular, curving walls, like the inside of a fairy-tale pumpkin or an animal den. The old man, an elementary school teacher who has wandered without fixed abode for over ten years now, tells us nine people live here, but I can’t imagine nine bodies asleep in these few square meters, not even fitted in like a jigsaw puzzle. The old teacher puts the shoes down in a sooty corner, lined up neatly.

We interview other families living in the grottoes and I have a picture taken to send home of me with two little Hazara brothers, beautiful and runny-nosed. They have blond hair that grows right back after being shaved bald and their eyes are two narrow fissures between cheekbone and eyebrow. I ask the bigger one how old he is—he looks six or seven, but answers that he doesn’t know, and doesn’t know his little brother’s age either.

The rock walls containing the non-Buddhas are like a huge stone book splayed open, two rectangles leaning on their long sides and joined at a 140-or 150-degree angle. This makes the daylight strike them at various slants, like asynchronous sundials. The black holes of the caverns embroider the surface; the towers stripe it vertically. When the shadows are accentuated and dramatic on one side, on the other they shorten and are absorbed in orange and red.

About halfway between the niches of the two non-Buddhas, which must be about a kilometer apart—no, maybe less, six or seven hundred meters—we see people gathered around a pile of big boxes. A distribution of humanitarian aid must be underway; that explains the empty caves. Everyone has gone running down. Curious, we draw close to the crowd.

Pieces of clothing are spilling out of the already-opened, upturned boxes, the kinds of things you’d find in open-air markets in Italy: jogging and basketball shoes with fancy soles, jackets loaded with zippers, military-cut pants. There is no order or line-up to receive the donations; the people stand in a circle around the boxes, the women as usual held at a distance, which makes you think it’s unlikely they’ll receive anything. The distribution is being run by four or five persons of uncertain nationality. One is sitting inside one of the huge boxes talking on a satellite phone. Every so often he fishes a pair of shoes from the nearby box and tosses it into the air. When they fall in the middle of the crowd, the shoes provoke a scramble, a skirmish. The boys fight over them. This seems to amuse the guy who repeats his launch, a parabola, as you would toss breadcrumbs to geese in a pond.

We ask who’s in charge of this gang. It’s a little guy with mirrored glasses and acne scars, Asiatic but not necessarily Afghan; no, wait, he could even be Latino, the type who bodyguards Al Pacino as a Cuban gangster. He has a heavy American accent, that’s for sure. He says he expected to find someone here to handle the distribution—he was only responsible for transport to Bamiyan, and by now his other trucks are back on the road to Kabul. He’d be perfectly happy if we took charge of all the stuff (it would certainly be in safer hands ...), but how can we? We have no means to transport it. An Afghan from our group whispers in my ear that he knows these guys—they pocket most of the money and almost nothing gets to the “supposed beneficiaries.” The money gets lost along the road. In the meantime, more shoes are flying. Boys with Kalashnikovs chase off other boys who look almost the same, whipping them with leather straps. The women sit, immobile, and don’t dare ask.

In the confusion I go talk to a Filipino unloader wearing gloves and a wool beret. He’s opening the boxes with a box cutter. The cartons are stamped with the initials of an American Protestant organization. I picture the pious ladies making the collection on Sunday, after services or at tea. The Filipino is from California. “The shoes are from California too and they’re really good shoes,” he says, and bursts out laughing. Then he disembowels more boxes. The fact that all this confusion happens at the foot of the sacred mountain makes the whole scene much clearer. The cries are lost in space. By now it’s impossible to interrupt this ceremony. The crowd would go wild. We leave it at our backs.

The smallest Buddha is a woman. I don’t know what that means, but everyone calls it the woman Buddha. It is 35 meters tall. On both sides of the immense niche in which it stood before they blew it up, shafts are tunneled that permit ascent alongside what were the giant’s flanks, with landings at various levels. I crouch down and thread myself inside the shaftway. The spiral stairs carved into the rock have extremely high steps. You have a long stretch from one up to the next, and we will pay for this later with cramps in our thighs. The first flight leads to a rock terrace facing a chapel that was once decorated with statues and frescoes. The paintings have been scraped away with maniacal care. Now there are only the names on the wall of those who have passed by and want to be remembered. Another flight carries us up another 20 or so meters, and at this altitude my head is already starting to spin. On one side there are large oval windows for observing the statue and I suffer from vertigo; furthermore, the rock—which doesn’t deserve the name because it looks like a friable, clayey impasto of crumbled stones—is riven with cracks, and it’s impossible not to think of the kilos of dynamite used to blow away the Buddhas and shake the whole mountain. (Parenthesis for explosives experts and anyone who appreciates a job well done: The removal of the statue succeeded 100 percent. It seems to have been detached by a huge knife, leaving a scar on the rock.) This second ramp, which we ascend grasping the rock with our hands and trying not to look out the window openings, leads to another grotto that looks over the valley and includes a second, round chapel, whose vault is covered with smoke-covered reliefs in triangle and lozenge shapes. Five or six of us have made it up this far and some are beginning to rub their thighs.

It’s not only the disproportionate stairs that play this nasty joke; I think it’s also a question of nerves. We are tense and excited, and so make uncoordinated movements that waste energy. I think I’ll stop here on this intermediate terrace. Vertigo impedes me from going any higher. I know how it works and it’s useless to try to overcome my fear—I just can’t handle it. I lose equilibrium; I feel like I’m falling, and it’s still worse when I see someone else on the brink of a precipice, like the last time I was at Chartres and watched my children stroll along the walkways on the outer flanks of the church, even though they weren’t even halfway up the cathedral. But after a few moments I convince myself that this time is different, and I set out to follow the others up the third flight, which climbs above the head of the non-Buddha. Two turns of the spiral and I find myself in front of another window that opens on nothingness. The sudden light blinds me, and this time the aperture is dug all the way down to the step my feet rest on, so it’s impossible not to look down. I do. I’m paralyzed. If I keep looking down I’ll fall forward right through that hole; if I turn toward the inside I’m afraid of stepping wrong and sliding in it anyway. I lean both hands on the stone and keep going up until I notice that the entire body of the staircase is separated from the rocky wall by a vertical fissure about a palm wide, as though it were getting ready to break away all at once. It’s completely idiotic, this. This whole thing is senseless. I’m going to die in Afghanistan as a tourist. I want to rush back down, but I’d have to pass by that two-meter hole where I’m sure to be sucked down like a ball in a pinball game—useless to work the flippers, you’re already gone. So I turn and go down backward on my hands and knees, testing each crumbling step.

Returning to the distribution site, the scene is still more confused. A truck has arrived and they’ve loaded half the boxes onto it, with three or four people to hold them in place, but when the truck heads away toward the road, it hits a curve and the boxes start to tip off and bounce down the hill. A couple of the armed local boys who are rather simplemindedly trying to keep the cargo in place by putting their arms around it have to jump down before they fall. At the sight of the lost boxes, a few people rush out of the crowd to loot them, and the soldiers whip them on the face and arms, though this doesn’t discourage them. They seem accustomed to such treatment; now the whole group closes in on the truck, waiting for something to fall off. Losing pieces on both sides, the retreating soldiers barely fend off the crowd, which dodges away just before ending up under the wheels, until finally the truck makes it onto the road that leads down to the base of the valley.

Over there the de-miners are at work. Only a few strips have been cleared, but people are running all over the place after the truck. Our chief goes to their chief in the mirrored glasses and says he’s going to report this squalid affair. “Go ahead,” the man snorts.

At the end of the day, a short trip to the third missing Buddha. We ride a stream bed right up under the rocky hillside fantastically riddled with caves and surmounted by ancient towers, when the sunset’s rays suddenly illuminate it with yellow against the white of the snowy mountains and the violet sky.

M. makes tagliatelle while listening to the radio broadcast old hits by the Police, Spandau Ballet, Huey Lewis (“I Want a New Drug”). I help him by sifting the flour through a sieve that catches little stones, fibrous splinters, and balls of some pink paper we’d rather not think about, since there’s only one thing in Afghanistan that’s pink ... We use it but no one speaks its name. While M. forcefully rolls out the dough with his farmwife arms, I surf video music channels on the satellite.

On the way to visit the third non-Buddha, Rafiq asked me about that Roman king who fought against the Moslems. Wait a moment, let’s see... you’re sure he was king of Rome? He strains to remember the name of this famous warrior... he was called... Iraches, Iralches... and finally it comes out that he means Herakles, Hercules. Sure, Hercules Against the Moslems could have been a plausible film in the 50s. He confuses the historical epochs of my part of the world in the same way as I confuse the epochs of his. I tell him that Hercules comes before Rome, before history—he’s the link in the chain between the world of the gods and the history of men. But for Rafiq there are no gods and history begins with the Prophet. Rafiq is a rather intransigent fundamentalist. In the office, he oversees the habits of the Afghan women clerks: how they dress, how they conduct themselves with us internationals, we who carry the germs of corruption—in fact we are the germs. He went to complain to his superiors because there was a girl wearing “sticky pants,” meaning tight pants.

Hazara women, small, robust, and full-breasted, carry bundles of sticks on their heads.

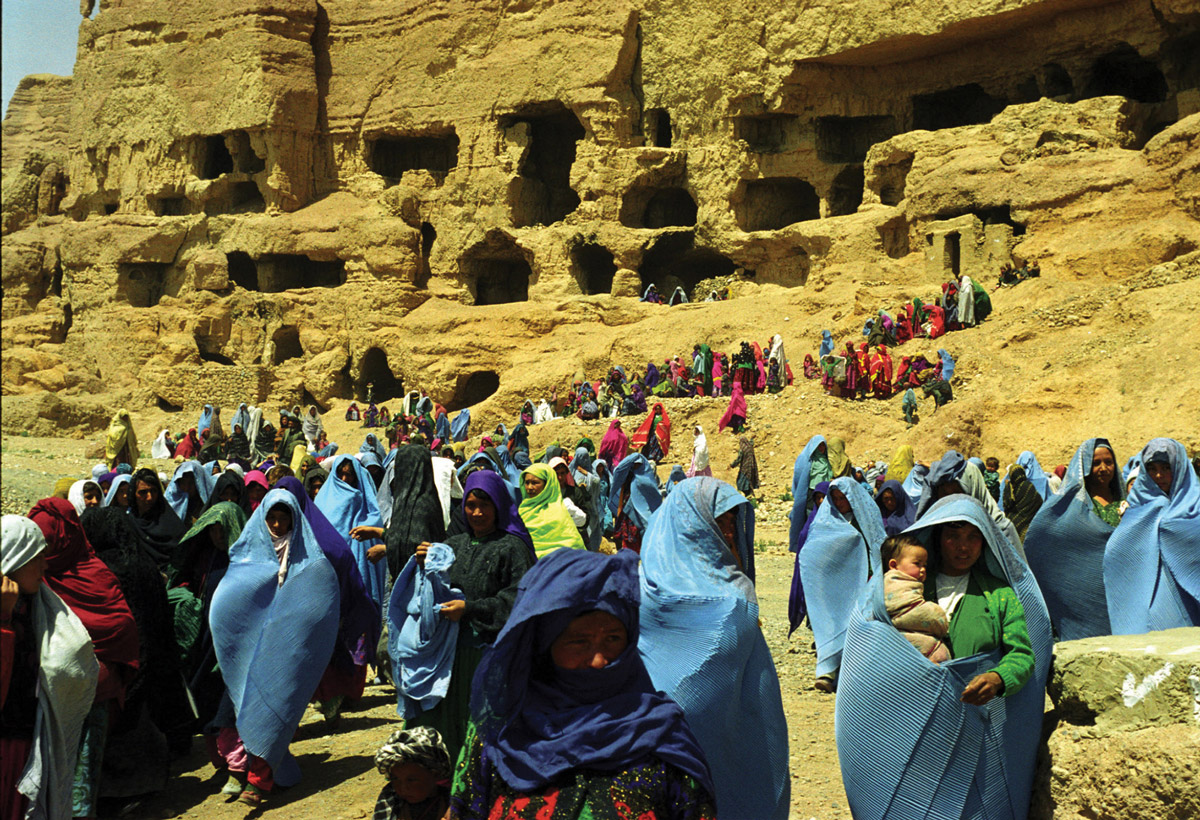

The Italian Ambassador arrives in Bamiyan. He’s a handsome man with white hair combed back, something of the sport sailor about him. With some apprehension we watch his plane emerge from the clouds and drop hard onto the gravel airstrip parallel to the white profile of the mountains. That’s the same little nine-seater that’s taking us back to Kabul this afternoon. The Ambassador is escorted by two big handsome athletic carabinieri with little backpacks and the relaxed air of guys who have the situation under control. We accompany them to meet the governor we saw yesterday. While the Ambassador is inside, we catch sight of a colorful crowd thickening below the niche of the Greater Buddha. It’s the preparatory gathering for the Loya Jirga, the great tribal parliament that will convene in a few days in Kabul. We head down there in our cars. I stay toward the rear and end up in a human river of women and children pouring into the valley to take their places before the men, aligned in formation on a rise perpendicular to the non-Buddha. At their backs stand the dozens of trucks that brought them to Bamiyan. These mass movements are accompanied by loudspeakers blaring orders and music. The government representative to the Loya Jirga tells us that the Tajiks (not all of them, only one part) have boycotted the assembly because their chief prohibited them from attending. Here the divisions follow not only ethnic but also religious borders (Shi’ite and Sunni), with further subcategories according to village, mountain versus valley people, etc. The spectacle below the niche of the non-Buddha is glorious: donkeys without masters running all over, adolescents with Kalashnikovs stretched out in the grass, women with exposed faces, children laughing and jumping ditches, we who don’t understand what’s going on. A video crew with a long fuzzy microphone fishes for comments from the people, and above this crowd sit pyramidal groups of women who have clambered up the mountain’s flanks, dozens of immobile, colorful women coming from the lateral grottoes within the colossal dark hole, the shadow of the Missing Buddha.

Not to pose as a negative theologian, but the presence of the Enlightened One can be perceived still more powerfully in the darkness of the niche. That emptiness attracts the whirling forces of the valley and reabsorbs them.

Translated by Thomas Simpson

- Albinati’s diary was published in Italy in 2002 as Il ritorno. An English translation of the entire text will be published in the UK by Hesperus Press in Fall 2003.

Edoardo Albinati was born in 1956 in Rome. He has published several books of fiction and poetry. He won the Alberto Moravia Literary Award in 1999 for his book Maggio selvaggio (Wild May), inspired by his experience as a teacher at Rebibbia, Italy’s largest prison.