On One Lost Hair

The final voyage of Horatio Nelson

Gregory Whitehead

eBay item # 928841754: a single hair from the head of Lord Horatio Nelson, Hero of Trafalgar, Vice Admiral of the Royal Navy, and savior of Great Britain. After parrying briefly with another bidder known as Lady Jahara, I placed a maximum bid of $52.50. A few hours later, I received the email, CONGRATULATIONS GREGORY WHITEHEAD, YOU ARE THE OWNER OF ONE NELSON HAIR, which arrived by priority mail two days later, together with an odd assembly of photocopied images and documents.

Anxious to learn more about the strange history of my fragmentary artifact, and to secure an expert review of its provenance, I asked my BBC collaborator, Neil McCarthy, to arrange a meeting with Dr. Colin White, the distinguished editor of The Nelson Companion, and an authority on the vast compendium of Nelson relics and memorabilia, many of which are now housed at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. The three of us met in a small conference room on an upper floor of the museum, where he scrutinized my tiny bit of the Vice Admiral with a mixture of mirth and disbelief:

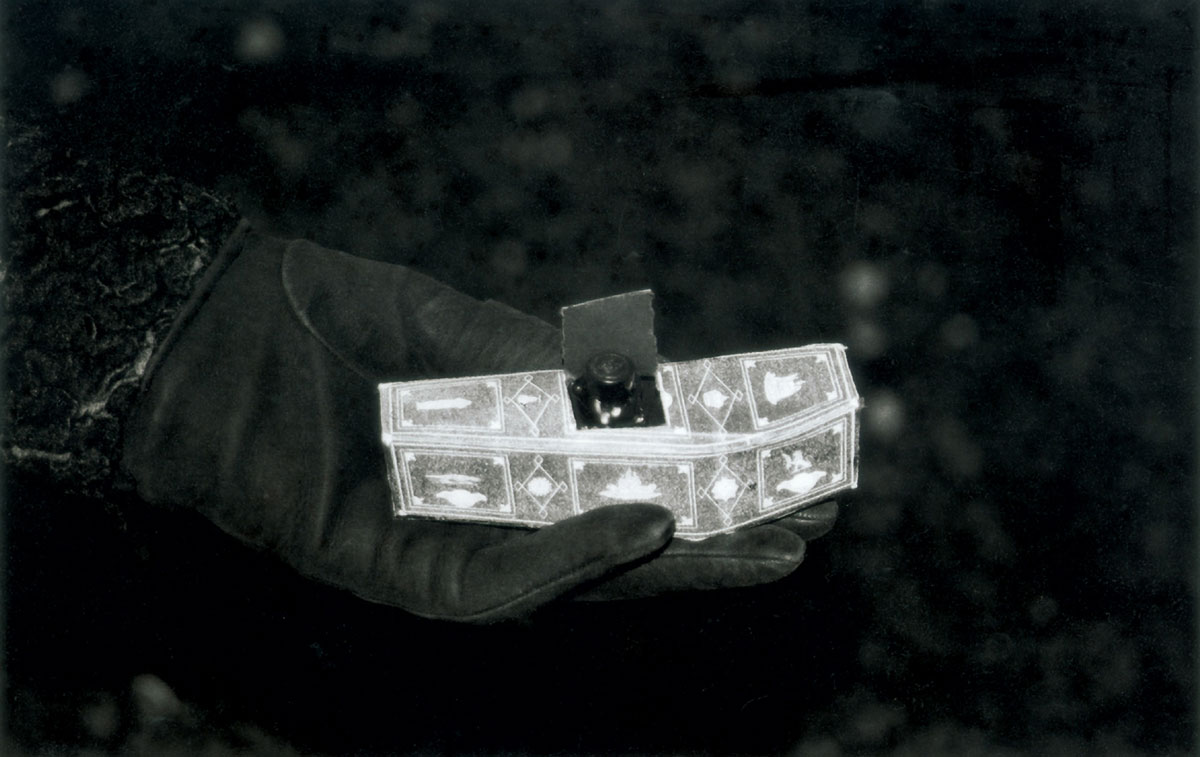

Well I have to say my first reaction is that somebody has presented it almost as a holy relic. I have never quite seen anything like this before. Somebody has managed to extract what looks like a single thin strand of hair and put it inside what could only be described as a monstrance; the sort of device they use for displaying the host in Anglo-Catholic churches, thus emphasizing the point that this is an extremely important item. It is the thinnest possible, tiniest piece of hair. Quite fascinating.We asked Dr. White if the provenance attributed to the relic, tracing it back to Nelson’s daughter Horatia, seemed at all plausible. He responded by recounting the details of Nelson’s death during the Battle of Trafalgar, picking up the action shortly after Nelson’s ship, the Victory, cut a vicious gash into the line of the French and Spanish Armada which, under the command of Villanueve, was attempting a hasty retreat to the relative safety of Cadiz:

The shot that killed Nelson was a musket ball fired from somewhere in the mizzen rigging, from the rearmost mast, possibly from the fighting top, although we can‘t be absolutely sure, and it struck him on the left shoulder and broke his collar bone and then cut through his lung, severing a pulmonary artery along the way, broke his back and lodged under his right collar bone; a very severe and very nasty wound. The sheer force of it threw him to the deck almost immediately. He was then taken down, as was the custom, right below the water line to the cockpit. Nelson was conscious that he was dying, and asked to see Captain Hardy, his flag captain, because he wanted to give him some final orders. When Hardy eventually came, Nelson gave him his last instructions, and one of the things he said was, “Pray let my dear Lady Hamilton have all my hair and everything belonging to me.” It is quite clear that Hardy kept some for himself, but most of the hair went to Emma, including the biggest piece of all, which is Nelson’s pigtail. That pigtail passed into the hands of Horatia Nelson, the daughter of Nelson and Emma. She would respond to requests from people asking her for a relic of her father, and the provenance that is with your relic is a letter from Horatia to one of her correspondents. So it is quite clear she sent this correspondent a chunk of hair from which this one tiny little strand has been extracted.From Captain Hardy to Lady Hamilton; from Lady Hamilton to Horatia; from Horatia to a friend; from the friend to an eBay entrepreneur; and from the eBay entrepreneur to me. But what next? A few minutes later, I stood in one of the main exhibition halls of the museum, directly in front of the case holding the “mother” pigtail, tucked into its cloth queue and deposited rather casually, it seemed to me, at the foot of Nelson’s Victory uniform, with its blackened hole in the left shoulder. Surely, it was not right to return my tiny hair to this sad queue!

I took the next water taxi back to London for a dinner meeting with my friend Jane Wildgoose, curator of the remarkable Wildgoose Memorial Library and a designer of memory theaters. Wildgoose had also recently convened an Oxford conference on the business of the flesh, and had thus become fluent in both the poetics and the ethics of private body parts. After a close examination of the monstrance and its many documents, she suggested we pay a visit to the crypt at Saint Paul’s Cathedral. The next morning, we stood next to an immense sarcophagus, in the company of the genial and learned Canon John Haliburton:

We are now directly under the dome, and what you see in front of you here is a monumental tomb. On top of it there is a black marble sarcophagus, which is surmounted by Nelson’s Viscount’s Coronet. Legend has it that he is not actually in the sarcophagus; he’s somewhere in the middle there.Though I knew from other sources that Nelson’s body had been shipped back to England from Trafalgar inside a cask of navy brandy, I resisted pressing the good Canon for details regarding final dispensation of the corpse, and instead inquired if the sarcophagus had ever been opened since the interment. He assured me that it had not. Sensing my hesitation over plunging headlong into the meat of the matter, Wildgoose ventured the story of my purchase, and asked whether there might be some procedure or protocol whereby we might restore our hair to the rest of Nelson’s remains. Canon John looked quite ashen at the mere suggestion, and hastened to educate us regarding church thinking as it pertains to the care and preservation of relics:

Relics of the saints are scattered all over the world. We distinguish in the church between primary relics, which are parts of their body, a bone, bits of hair, and secondary relics, which are bits that belong to them—a handkerchief or something like that. The belief in the relic is, somehow, to have a little bit of somebody; well, it gives you the presence of the saint. It’s sort of like a lover wanting a lock of your hair—just like that.

And just like that, we were reminded that my hair was indeed once a precious possession of Nelson’s lover, Emma Hamilton. Were we not in a position to play some small hand in fulfilling Nelson’s original dying wish that Emma should retain ownership of all of his hair? Wildgoose made a quick phone call and we soon found ourselves in the company of Dr. Ruth Richardson, author of a brilliant ethical and philosophical study titled Death, Dissection and the Destitute. Dr. Richardson assured us that we were on terra firma, ethically speaking, when probing Canon John for an ultimate sanction to return our tiny bit of pigtail to the whole of Nelson:

The belief system associated with integral burial comes from a quote in the Bible that says, “Not a hair on your head should be lost.” You know it’s like God regarding every sparrow that falls, that every part of you is somehow you and somehow special, and God knows where it is. Nelson knew his hair was going to be cut off, and even if he hadn‘t consented to it, he would have known anyway because it was a very common thing. In the 18th century, all sorts of things were made out of people’s hair; it was the one incorruptible part, apart from the skeleton, and people don‘t want to keep skeletons, which are rightfully allowed to decompose, but hair was one thing that people did keep. So he would’ve known that his would’ve been used but he didn’t know that it would be used like this, and it’s this that I think is really quite vile.How then, could we set the story right? Dr. Richardson suggested a resolution that would launch us back to the water’s edge:

I would certainly like to liberate it from this plastic packet. I think that is probably the most important thing to do with it. Something appropriate; something romantic. Bury it at sea, you know, some wonderful appropriate gesture.Inspired by her counsel, and following a long night of meticulous preparations conducted inside the Wildgoose Memorial Library, we ferried back to Greenwich the following afternoon to a pub named after the Battle of Trafalgar so as to prepare the hair for its final journey. As Wildgoose arranged Nelson’s memory theater upon a corner table inside The Trafalgar, she described the scene, for the record:

We are sitting beneath a reproduction painting of Horatio in his uniform, wearing his medals, and wearing what looks like a portrait of Emma, as well. It‘s quite dark and I have set out a little shrine to Horatio and Emma. I have lit a pair of candles and between the candles is a semi-circular white marble slab. On the slab is a little miniature reproduction of Horatio‘s coffin, painted and decorated. I‘ve opened the lid of the miniature coffin by cutting into the area that carried the deposition describing who Nelson was, and into that opening I‘ve inserted a small bottle. This bottle will be the receptacle for the hair when we send it on its way. Laid out in front of the coffin are postcards: one of the Schmidt portrait of Horatio and the other one of the Schmidt portrait of Emma, which Horatio kept in his cabin and described as his guardian angel.

We then set to work with a sharp utility knife, aiming to liberate the strand from its wretched plastic monstrance. Using small tweezers, we dipped the hair into a glass of house brandy and deposited it inside the bottle, which was then nestled inside the miniature coffin. Following a brief toast—that this one lost hair might soon be reunited with the spirit of Horatio’s beloved Emma—we each drank from the brandy and proceeded to the edge of the River Thames. Wildgoose then placed the coffin into the water and set Nelson loose upon one last voyage:

Right down here on the edge of the Thames,

where so many bits of detritus land at every tide,

we are going to set this little boat on its way.

I‘m just lowering the little coffin down to the water

and as the next wave comes up I‘m going to let it go.

Here it comes. ... It’s off! And it has capsized!

But it’s going ... on its way.

Oh look! The coffin is about three yards out.

Floating freely on this cold tide.

The little door that I made in it, where the deposition was…

It is almost like a little sail, as it floats away. (...)

So peaceful.

Author’s Note

It was the keen eye of Jane Wildgoose that first uncovered the anagram ON ONE LOST HAIR in the name Horatio Nelson, among such other finds as HALT NO EROSION. I should also commend the audio trickster Neil McCarthy for his skillful recording of the above

journey for a BBC broadcast version of our tale (excerpted on www.gregorywhitehead.net), and Harry Willis Fleming for his exceptional photographic documentation. The year 2005 marks the bicentennial of Nelson’s death at Trafalgar, and one might expect the market to be flooded with hair of uncertain provenance.

Gregory Whitehead is the author of numerous essays and broadcasts recounting his forays into the murky world of celebrity necrobilia. For more information, visit gregorywhitehead.net.