Harnessing Niagara Falls

Lighting the Path of Progress

Sasha Archibald

Thus is the force of Niagara transformed into electricity, which is carried to Buffalo by a cable no larger than a woman’s wrist should be.

—Hartley Davis, “The City of Living Light,” Munsey’s Magazine, 1901

General Electric’s corporate history, Men and Volts, includes a long chapter devoted to the moment in the late nineteenth century when “electrical men awaken[ed] to the possibilities of the giant working in their whirling dynamos” —the “giant” being Niagara Falls and the “whirling dynamos” the hydroelectric power generators installed there in 1896.[1] Even before Niagara was supplying energy for the nearby city of Buffalo, New York, GE was keen to announce its control over the resource; they were, of course, equally eager to acclimate the American public to electric light. An opportunity presented itself on both accounts in the form of a world’s fair. With financial backing from GE, it was decided that the 1901 Pan-American World’s Exposition would be held in Buffalo, and its explicit raison d’être to “show the force of Niagara Falls conquered by the commanding thought of man.” As covered by the national press, the story of the Pan-American Exposition was also “The Wonderful Story of the Chaining of Niagara,” “The Slavery of Electrical Energy for Man,” or, as Men and Volts put it, “Niagara’s First Harness.”

The exposition’s eight million visitors proceeded through a monumental arch, the Triumphal Causeway, to find themselves on a 15,000-foot esplanade that stretched the length of the fair. The esplanade was designed as an allegorized Path of Progress, meaning that the location of various pavilions depended on their contents. The horticulture building, for instance, representing the Fruits of Nature, was closer to the fair’s entrance than the theater building, representing the Fruits of Man, while the mineralogy pavilion was closer still. The color of each pavilion underscored this narrative. C.Y. Turner, Director of Color, determined that the percentage of white in a given color indicated that color’s level of cultural refinement and painted buildings accordingly, such that the Path of Progress grew progressively more pastel in hue.[2] If visitors were perhaps not attentive to the symbolism of the fading colors, the esplanade was lined with 500 plaster sculptures tirelessly telling the story of Progress in figurative allegory.

The endpoint of the Path of Progress and the apotheosis of the entire exposition was the Electric Tower, a 390-foot edifice painted in ivory, gold, and pale green—darker shades at the base and lighter at the tip—and topped with a sparkling white Goddess of Light statue. The base of the tower housed a mini-Falls, a seventy by thirty-foot aperture that gushed 11,000 gallons of water per minute, while the cupola offered a glimpse of Niagara itself. From the top of the Tower a spotlight shone straight into the air. Identical to those that adorned the 1889 Eiffel Tower and the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Tower, the spotlight was the most retrograde element of the exposition’s illumination scheme. In fact, as its planners hoped, the distinguishing characteristic of the Pan-American was its illumination: not only larger in scale and a hundred times brighter than any previous light display, the exposition pioneered the use of light as an aesthetic rather than purely utilitarian medium.

GE Engineers Luther Stieringer and Henry Rustin’s method was deceptively simple. Every possible edge of each building, walkway, cornice, and window was lined with relatively dim incandescent lamps, meticulously spaced at three-foot intervals. While the darkness obliterated form, the small white lights reiterated line, transforming the exposition into a series of perfect geometric shapes. The direct descendant of this kind of illumination is suburban homes decorated with Christmas lights, but it would be a mistake to make the comparison. Even the best Christmas light displays cannot be described as “a paralyzing, deadening drug,”[3] or a “modern miracle that conveys something of the ecstasy of the sun-worshiper.”[4]

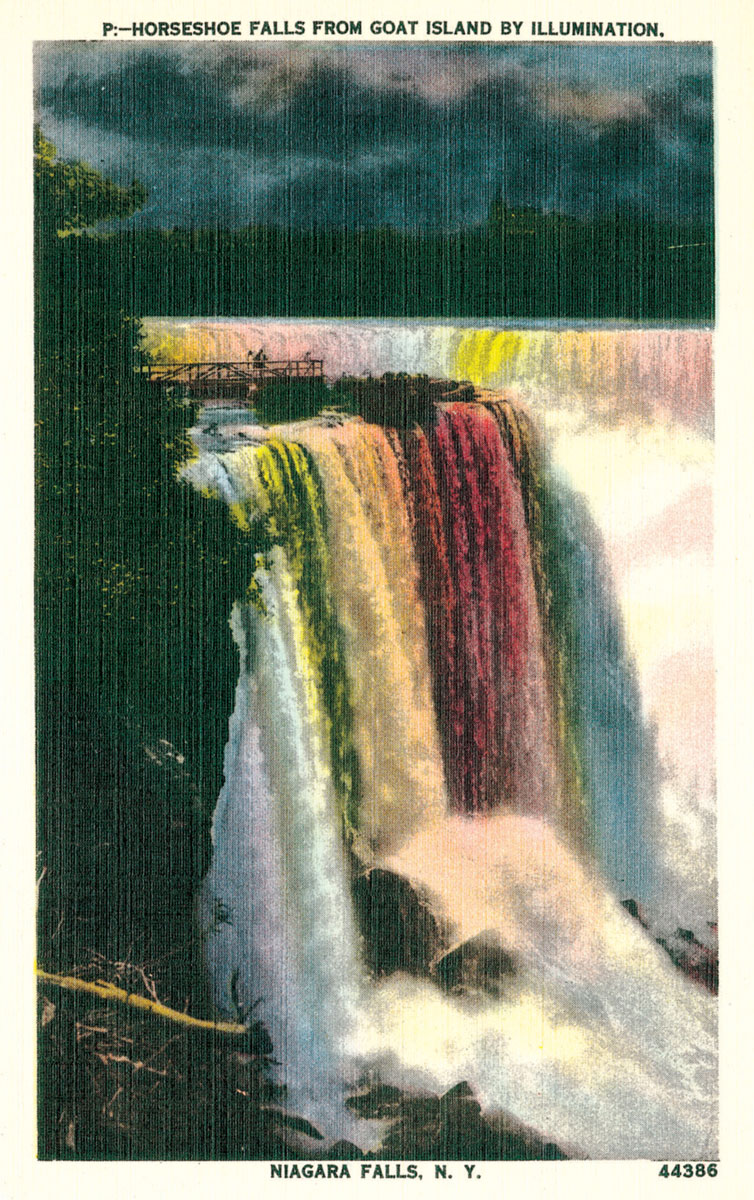

One especially omniscient critic noted the way the lights simplified and sanitized the exposition landscape and hailed the birth of “nocturnal architecture.”[5] Indeed, in the next twenty years, electric signs, skyscraper floodlights, illuminated shop windows, and street lighting would revolutionize nighttime urban landscapes, and a few rural landscapes as well—including that of Niagara Falls. In the summer of 1907, a young GE engineer named William D’Arcy Ryan installed thirty-one thirty-inch colored searchlights under and above the Falls’ swirling currents. Perhaps inspired by the landscape painter Albert Bierstadt, who in 1884 had lit heaps of gunpowder beneath the Falls, Ryan softened the spotlights’ 1,110,000,000 aggregate candlepower (nearly twice the brilliance of the midday sun) with exploding smoke bombs. Despite the smoke and voltage, viewers found the final effect soft, ethereal, and romantic. Although electricity was everywhere associated with the technological promise of the future, and although improving upon natural wonders with artificial light was a profoundly new idea, Ryan’s treatment managed to evoke nostalgia. Nostalgia for what? For the moment before Niagara’s electrification: “For the first time since a factory was erected to draw its power from the rushing water [of Niagara],” The New York Tribune wrote, “the garish outlines of the bleak brick buildings were gone and in their place ... were the falls in their old glory.”[6]

- John Winthrop Hammond, Men and Volts, (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1941), p. 234.

- With one reviewer at least, Turner’s color scheme backfired. Hartley Davis, whose rave review of the illumination is cited in this article’s epigraph, wrote, “Mr. Turner tries to tell the story of man’s progress in the colors, as I understand it. It is a sad, faded story, if the colors are to be credited. The washed out blues and yellows would indicate that poor, feeble man was discouraged the greater part of the time.” See Hartley Davis, “The City of Living Light: The Wonderful Illumination that is the Most Striking and Beautiful Feature of the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo—The Predominance of the Spectacular Element in the Display,” Munsey’s Magazine, October 1901, pp. 122, 128.

- Ibid., p. 116.

- David Gray, “The City of Light,” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, September 1901, p. 673.

- Ibid.

- The New York Tribune, 5 September 1907. Cited in the 1925 General Electric company report “Beginning and development of illuminating engineering,” General Electric Co. Archives, J. W. Hammond File L:1038; Schenectady Museum, Schenectady, NY.

Sasha Archibald is associate editor of Cabinet.