The Reified Lozenge

The semiotics of pill geometry

Frederick Gross

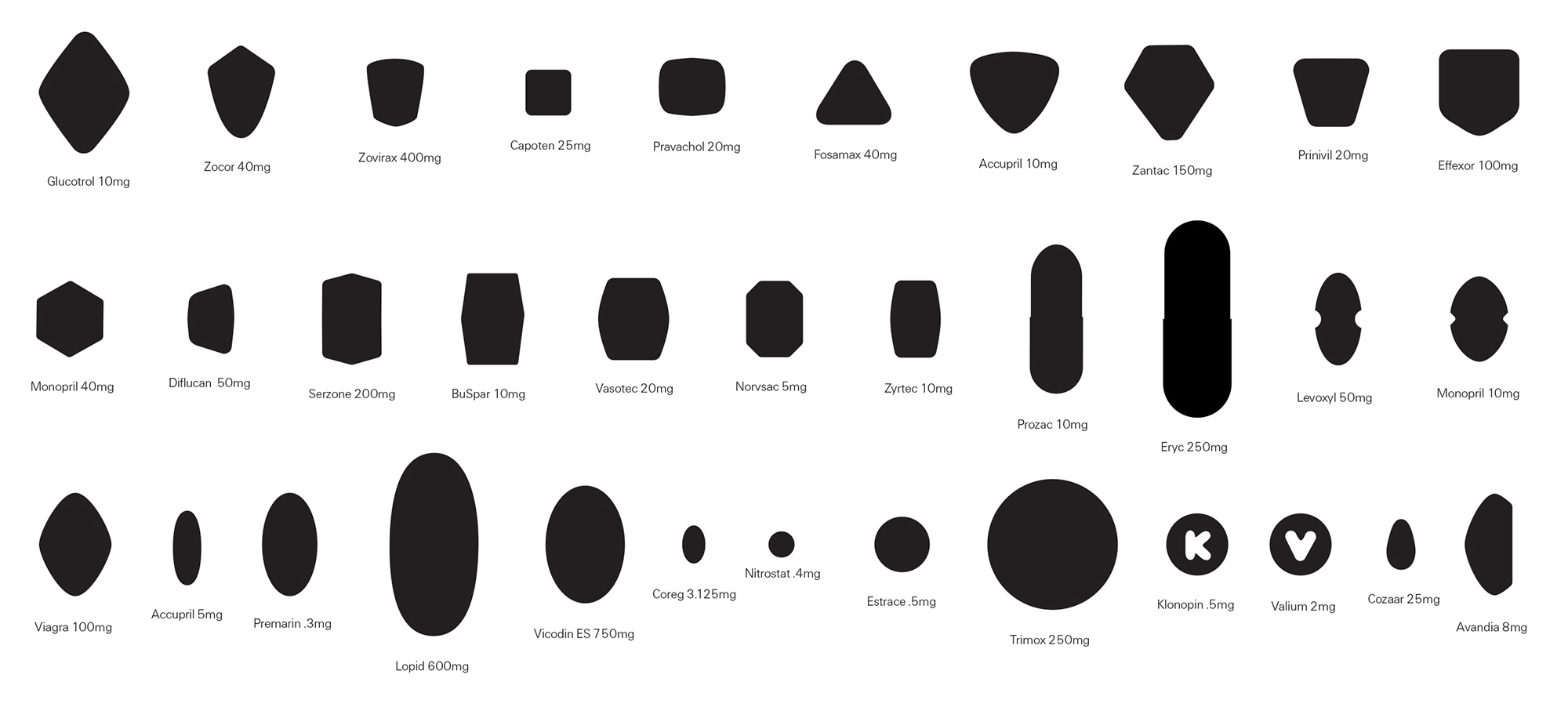

Pharmaceutical advertisements on TV aim to guide those with relatively harmless physical and mental symptoms to the quick self-diagnosis of a condition that can only be cured by a colorful pill. The aerodynamic shape and slick coating of these pills suggest the practical—ease of swallowing—and the technological—we are ingesting a small, precisely engineered capsule that will enter our unknowable interior recesses and make the necessary repairs. The colors of these pills are considered with great care. Nexium’s sexy purple with three yellow stripes offers a perfect blend of space-age style and edibility. Purple obviously signifies grape, a cool color that will soothe your chronic heartburn. But purple also intimates the offbeat and quirky, the chosen color of the individual with a touch of creative talent, while the three yellow stripes give the sporty appearance of military rank. The periwinkle-blue Viagra opts for a more geometrical design, a diamond shape indicating that a mathematical clarity is being applied toward ending the heartbreak of erectile dysfunction.

Every time we witness one of these commercials with yummy pills floating in the angelic skies of mental health, the pill seems to be infused with the air of divinity. Why is that? The answer may lie in the history of the ornamental lozenge form. By virtue of its advertisement, the pill retains the conceptual signifiers of the lozenge, but is reified as a commodity. The term “reified lozenge” represents the historical passage from lozenge to pill.[1]

Webster’s definition of the lozenge locates diverse references. Geometrically, the lozenge is a figure with four equal sides and two acute and two obtuse angles: a diamond or rhombus. The lozenge entered the popular visual lexicon in medieval heraldry as a diamond-shaped form on a shield, or the shape of the shield itself—a shape that, besides protecting its owner from harm, was adorned with the signifiers of that person’s identity. The lozenge was soon incorporated into architectural ornamentation, usually within an ecclesiastical context. In the tympana of cathedrals, Christ judged the living and the dead in an ovoid lozenge form called a mandorla. Borromini engaged the lozenge in the cylindrical aedicule of his famous S. Carlo alle Quattro Fontane (1665–67) in Rome. This form was the focal point of the undulating façade, giving the illusion of forward thrust. In each cathedral, the lozenge appears to the viewer at a crucial juncture between exterior and interior, between secular and sacred space.

For Louis Sullivan, the ornamental lozenge appears in the shape of the seed, or what he called the “germ.” The metaphor of organic growth central to Sullivan’s architectural epistemology was most fundamentally articulated in the winged seed of the Sycamore tree. The germ was featured on the first page of Sullivan’s A System of Architectural Ornament According with a Philosophy of Man’s Powers, published in 1924, the year of his death. Under the image, Sullivan placed a Nietzschean caption: “The Germ is the real thing: the seat of identity. Within its delicate mechanism lies the will to power, the function of which is to seek and eventually to find its full expression in form.”[2] By incorporating the lozenge into architectural ornamentation, Sullivan wanted to draw a comparison for the viewer between the seed and humankind’s potential for creativity.

In the more streamlined, aerodynamic modernist consciousness, the diamond-shaped lozenge-seed lost some of its direct referentiality as organic metaphor, becoming an abstraction that alluded to a higher state of awareness. Its planar geometry gives structure to Suprematist paintings by Malevich and the Neo-Plasticism of Mondrian, whose lozenge forms and canvases echoed shapes both artists had seen in churches. For Malevich and Mondrian, the lozenge was part of a larger messianic system of representation connecting religious forms of the past with abstract compositions of the present.

The spiritually uplifting connotations of the lozenge were questioned during the cultural revolutions of the 1960s. There were ironic and even sinister consequences of the lozenge to be explored. In Edward Gorey’s surreal, alphabetically organized “The Fatal Lozenge” (1960), the “Fetishist, the “Governess,” and the “Hermit,” to name a few, are part of a group of 26 illustrations, each accompanied by a quatrain of verse which ostensibly refers to the moment in which the subject’s demise is either contemplated or affirmed in the mind. For example, “The GOVERNESS up in the attic / Attempts to make a cup of tea; / Her mind grows daily more erratic / From Cold and hunger and ennui.”[3] Each line of the quatrain comprises a side of a textual lozenge which, in typical Gorey fashion, suggests the quaintly diabolical.

In the late 1960s, Richard Artschwager’s “blps” (pronounced blips) alluded to the lozenge form, but in a more generic way that echoed Pop’s emphasis on the banal, the repetitive, and the mass-produced. For Artschwager, the “blp” was a pixel or Benday dot separated from its photographic context. Appearing on buildings and floating on gallery walls, Artschwager’s “blp” referenced the architectural lozenge, but its rounded edges suggested a pill. For Artschwager, the “blp” was a punctuation mark in space linked to other Artschwager “blps,” creating a “realm of absolute, arbitrary space embedded in contingent, accidental space. Where the two coincide (at each blp) they reveal each other paradoxically as both absolute and contingent.”[4] On the façades of buildings the “blp” became a floating signifier, suggesting the architectural lozenge but ultimately confounding the viewer’s expectations. Artschwager’s obtuse conceptualist meanings stripped the architectural lozenge of its spiritual connotations.

But the lozenge would not lose its connection to religion. Gerhard Richter’s recent “Abstract Picture (Rhombus)” series of 1998—six rhomboid canvases of slightly varying dimensions—were originally intended for a Catholic church. Their warm, orange-red monochrome surfaces, painted over blues, blacks, greens, and yellows, have a meditative, almost mystical quality attained through the careful layering and dragging of color. They float in the space of the gallery wall and transmit color in discreet, repetitive planes, like individual sheets of stained glass in a row of clerestory windows.

The transformation of lozenge to pill is also located in the process of naming. A brief pharmacological etymology links the pill of TV commercials with the history of the architectural lozenge. Pax, the root of Paxil (paroxetine), is Latin for “peace.” According to Webster’s, Pax was also a word for a tablet or board decorated with a figure of the Virgin Mary or a saint that was, in medieval times, kissed before the communion by the priest and then by the people. It symbolized “a kiss of peace.” The spiritual aura of the Pax was transmitted to the lips of the believer. The name Paxil, then, suggests a quasi-religious relationship between tablet, or lozenge, and mouth.[5] Zoloft (sertraline) makes use of the Greek root Zo, for animal life. With Zoloft, apparently, the human animal is lobbed aloft into the clear skies of psychic well-being. The connection of lozenge to pill, then, is in the pill’s retention of the lozenge’s auratic connotation. Take it and your soul will be saved.

- Reification is a term with many contestable shades of philosophical and theoretical meaning. My use of the term alludes to Marx’s connection of reification with commodity fetishism, and Lukács’s consideration of reification as indicative of an incomplete or false consciousness. I am also interested in Bakhtin’s use of the term: For Bakhtin, reification takes the form of monologism (one prevalent, authorial voice), which prevents novels from doing justice to the multiplicity of human experience and otherness. As with monologism, the pill quells symptoms that do not fit the socially contingent rubric of “normal behavior.” For an in-depth analysis of reification according to Lukács and Bakhtin, see Galin Tihanov, “Reification and Dialogue: Aspects of the Theory of Culture in Lukács and Bakhtin” (The Bakhtin Center Papers Online: The Bakhtin Centre), 1995, www.shef.ac.uk/uni /academic/A-C/bakh/tihanov.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture, A Critical History, 3rd ed. (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1992), p. 56.

- Edward Gorey, “The Fatal Lozenge” in Amphigorey (New York: Berkeley/Windhover Books, 1978).

- Artschwager quoted in Richard Armstrong, et al, Richard Artschwager’s Theme(s), exh. cat. (Buffalo: Albright-Knox Gallery, 1979), p. 18.

- In Pills-a-Go-Go (Venice, CA: Feral House, 1999), Jim Hogshire compares the pill to the Holy Eucharist: “In this analogy the pill—or host—is capable of miraculous things but only if it is treated in a certain ritualistic way. Thus, a high priest (your doctor) must first authorize its use in accordance with proper canon. It must be further consecrated by another level of priest (your pharmacist) who will place it into your outstretched hands from a counter three feet above your head.” p. 11.

Frederick Gross is an art historian living in Fort Greene, Brooklyn. He is writing a dissertation in the Department of Art History at the CUNY Graduate Center.