By the Numbers: An Interview with William L. Bird, Jr.

Painting a picture of the middle class

Sasha Archibald, David Serlin, and William L. Bird Jr.

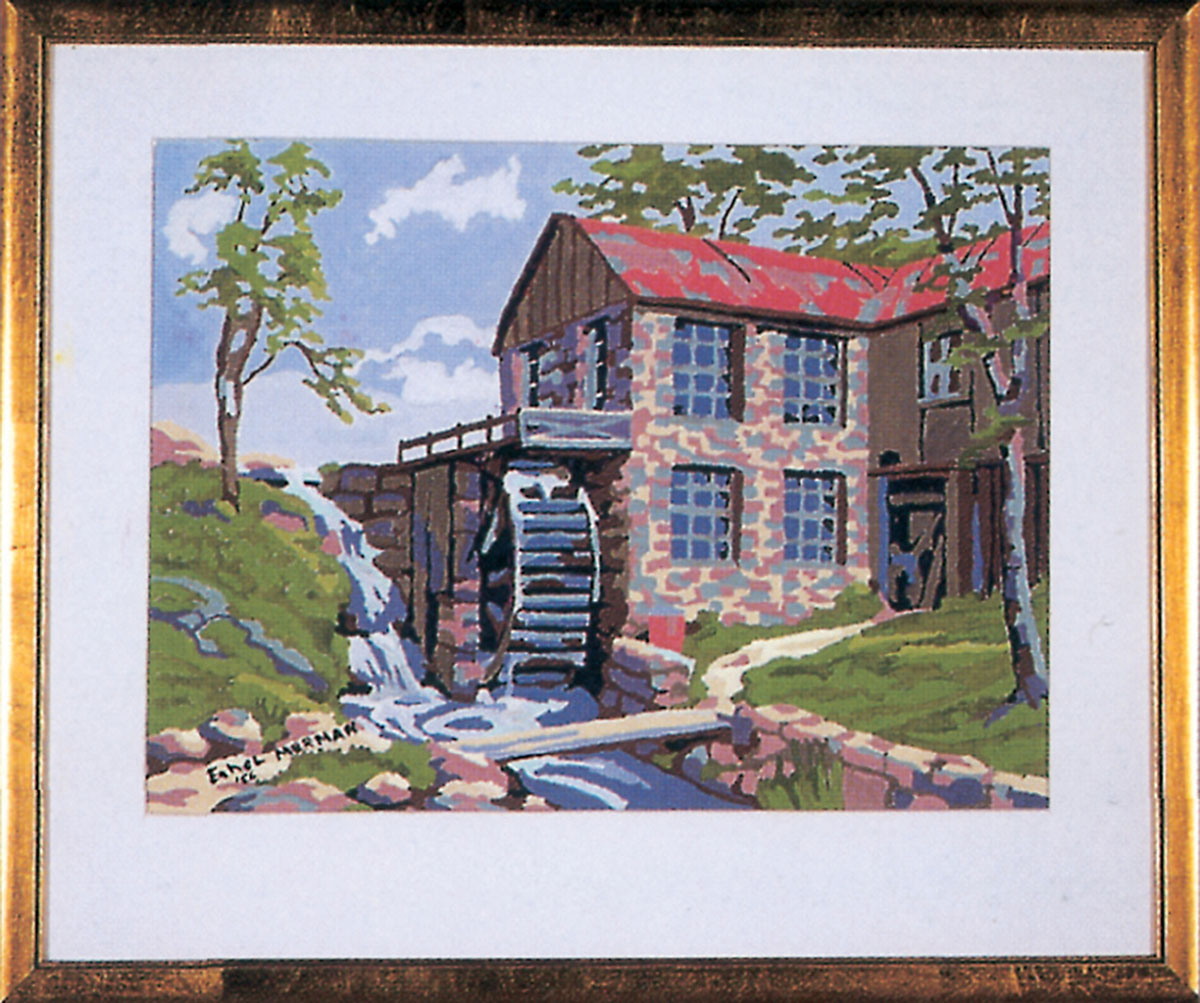

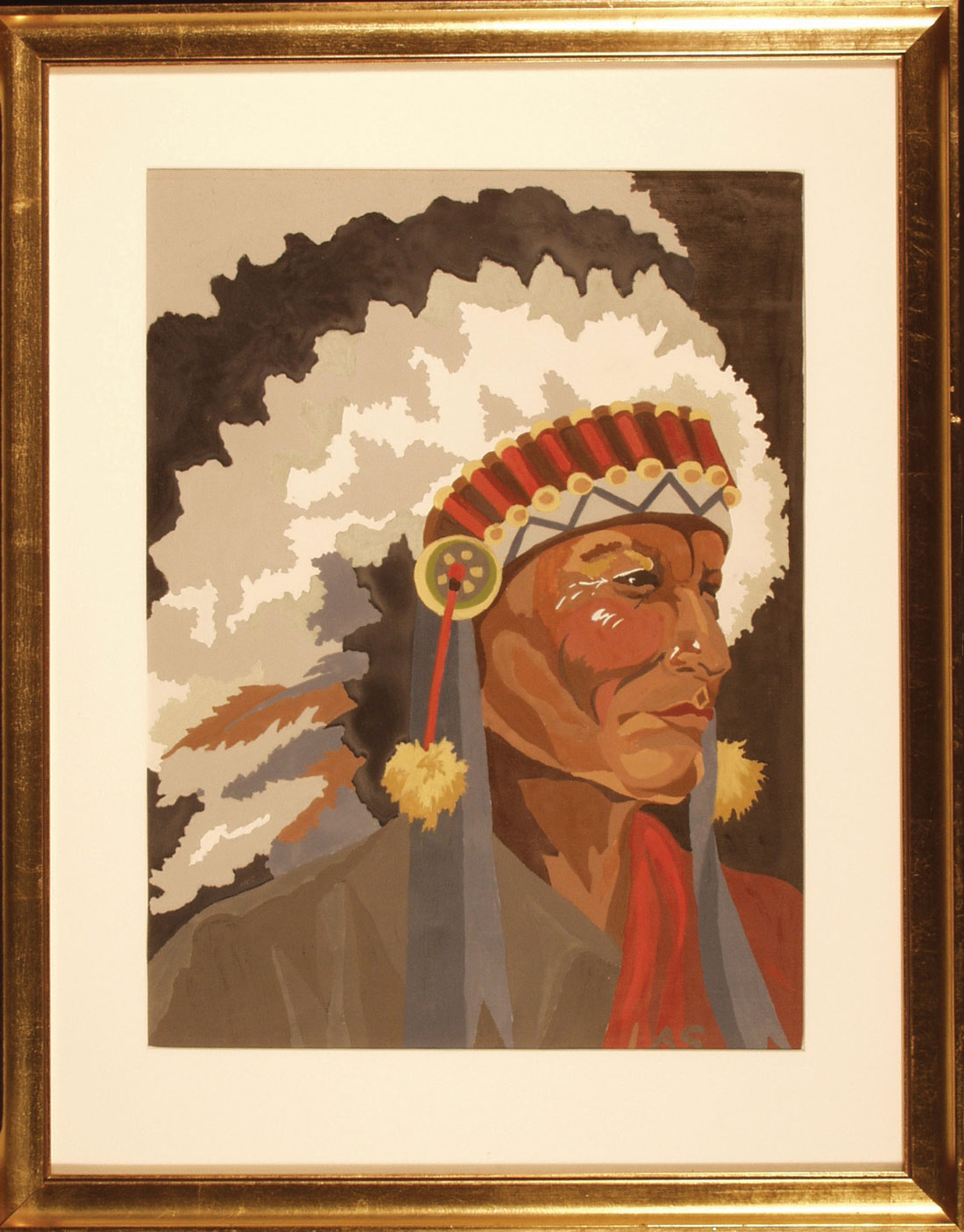

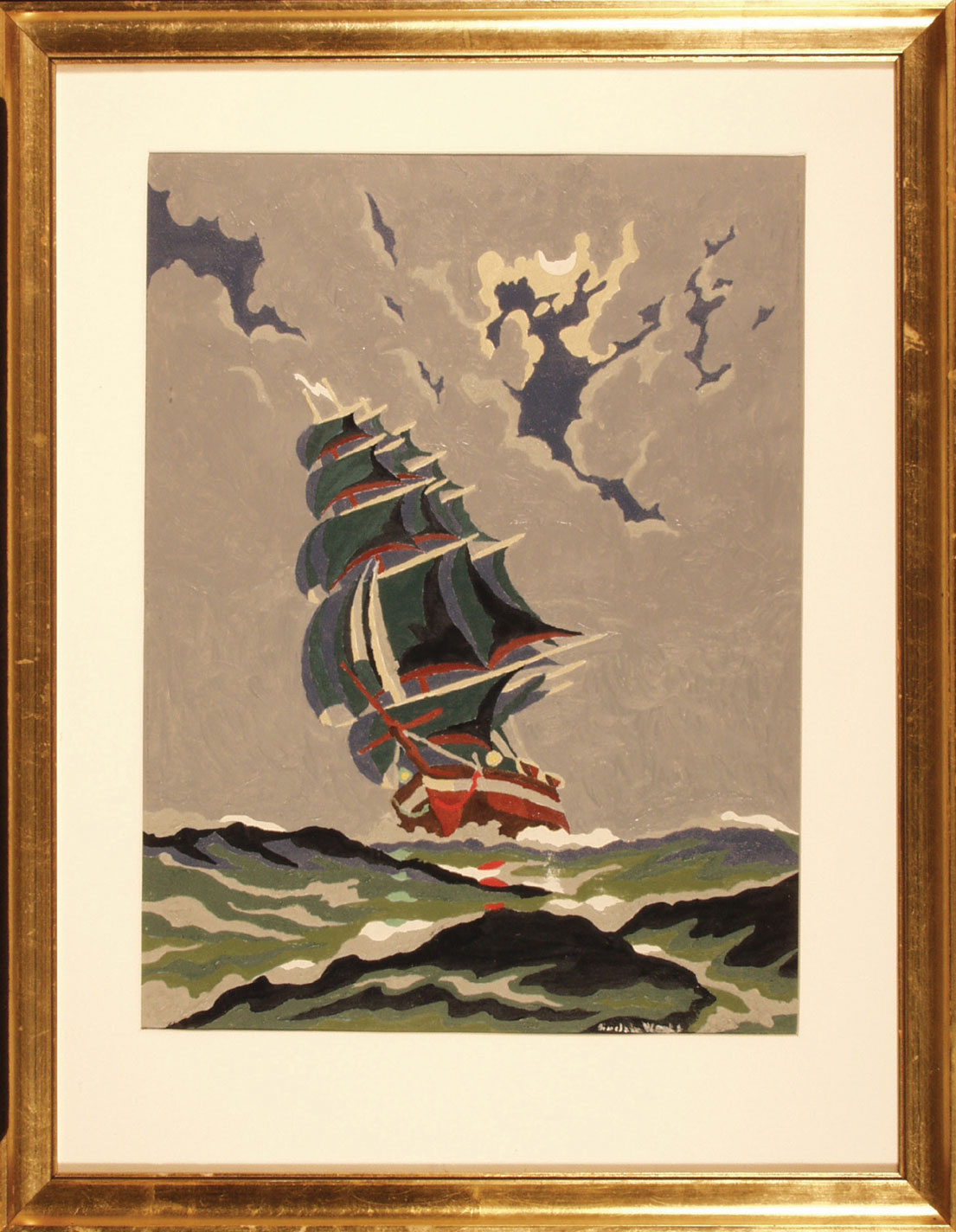

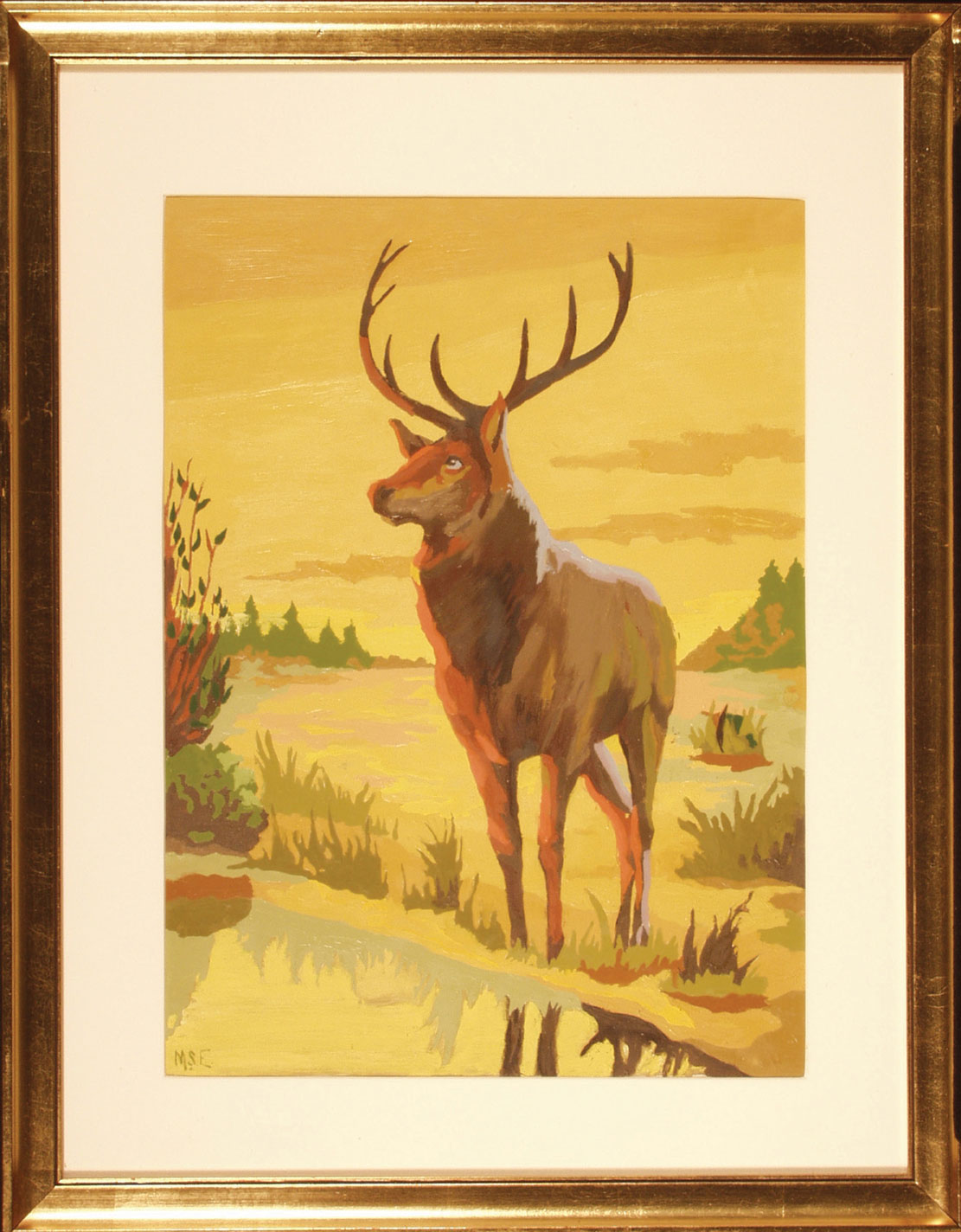

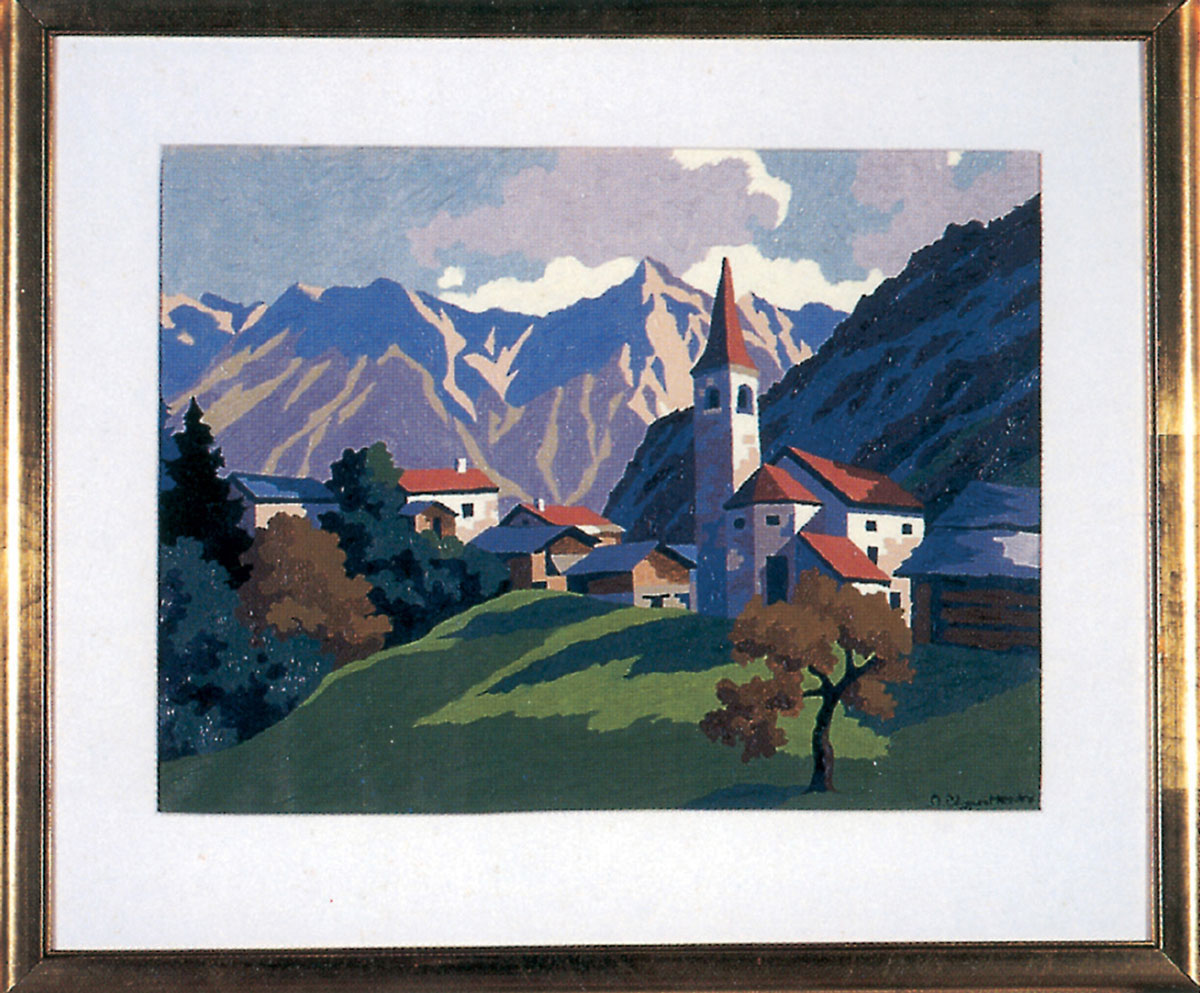

Paint by numbers was an immensely popular leisure activity that occupied middle-class Americans in the early to mid-1950s. Paint by number kits, cheaply purchased at drug stores or art and craft supply stores, were sold as a boxed set that included paints, brushes, and a canvas printed with a blue line drawing; the drawing’s numbered sections corresponded to specific paint colors. Although paint by numbers varied in size and detail, the genre came to denote a fairly standard color palette (the same muted shades as the era’s living room décor) and set of subjects: pets, barns, ballerinas, landscapes, clowns, flowers, and variations on cross-cultural themes such as Parisian street scenes, Indian chiefs, Latin guitarists, and Oriental maidens.

Paint by numbers seems to have been conceived by two companies simultaneously in the late 1940s. The kits were eventually marketed by 35 competing companies, the largest and most prolific merchandiser being Palmer Paint with their brand name Craft Master. Under the direction of president Max Klein and art department director Dan Robbins, the Palmer Paint plant in Detroit, Michigan, abandoned their business in flesh-tone mannequin paint and bulk tempera powders in 1951 and began producing paint by number kits. In 1953, only two years after Craft Master made its debut at Macy’s annual New York Toy Fair and a year in which the American hobby industry did some $80 million total in retail—most of which was paint by number sales (and that at $2.50/kit)—Palmer Paint employed no less than 65 artists. Klein built a second production factory in Canada in 1954 and began marketing paint by numbers in England, Japan, and Australia, although the kits’ international sales never approached their domestic success. The trend, however, even in America, was short-lived; by the close of the 50s, popular culture was on to other things. Max Klein left Palmer Paint near bankruptcy in 1956, only five years after the first paint by number sales.

The commercial success of paint by numbers provided early evidence of the purportedly despondent state of American mass culture; the charges leveled against paint by numbers in the 1950s—formless, mindless, didactic— are still habitually replicated in contemporary critiques of mainstream American culture. Tellingly, paint by numbers initially inflamed cultural critics not so much on the basis of its formal qualities but by the claim, made by consumers and producers alike, that the numbered paintings actually qualified as art. The aggressive hostility voiced in protest of this presumption, as William L. Bird, Jr. suggests in Paint By Number: The How-To Craze that Swept the Nation (2001), can be interpreted as the reaction of an intellectual elite threatened by the expanding middle class after World War II—specifically, a middle class with its own cultural aspirations. Paint by numbers, he writes, “became a vessel for anxieties about mass culture’s intrusion in to the well-cultured world of taste and social class.”

Bird is a historian and curator at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, where in 2001 he organized an exhibition on paint by numbers on which his book is based. He spoke to Sasha Archibald and David Serlin from Washington D.C. by telephone in September 2003.

Cabinet: How did you become interested in paint by numbers, and when did you conceive of the idea for the exhibition?

William L. Bird, Jr.: I grew up in a subdivision in Hyattsville, Maryland, a suburb of Washington, D.C., and I’ve always remembered the paint by number hobby. When I was a kid, I saw one in a friend’s basement; I can’t remember the friend and I can’t remember the basement, but I remember this half-completed canvas on an easel. Years later, in the early 1990s, I started noticing that people had begun to collect paint by numbers but that there seemed to be some confusion as to whether it was art or kitsch that was being collected. Around this time I read an argument by Michael O’Donoghue in House and Garden that if you enjoy looking at things like paint by numbers, you shouldn’t have to apologize for it. This opened up all kinds of cultural tensions that I found in my own work in the museum. When the museum was offered a wonderful collection of paint by number trade materials and pamphlets by Jacquelyn Shiffman, the daughter of Max Klein, who was the owner and president of Palmer Paint, they asked me if I was interested.

Are there any historical precedents for paint by numbers?

Dan Robbins, the art director of Palmer Paint, came from a vocational art training background in Detroit but started at Palmer Paint in package design. When the company was brainstorming new products, Robbins recalled the story of Leonardo de Vinci who assigned numbered portions of artwork to his students and assistants to complete. After Robbins conceived the idea, Klein paid for a patent search and the patent attorneys told them that the process had been patented in the 1920s.

The actual technique?

The method of keying a composition in a set, with numbered or lettered sections. They found several patented varieties but the earliest example I’m aware of is the Tom Sawyer paint by numbers set marketed in 1923, a children’s storyboard that could be painted. Even without a patent, Klein decided to take the risk and Palmer Paint began production. Although no one came after them, you quickly had dozens of companies flooding the market. What made Palmer Paint a success was the high quality of Robbins’s and his staff’s work. The other half of the equation was Klein’s genius for marketing. Paint by numbers débuted at the Macy’s Toy Fair. Robbins has this story about how before the fair, Klein passed out some petty cash to strangers to come in and purchase sets. The sets flew off the shelf and Macy’s was impressed but Robbins never knew whether the sales were all part of Klein’s gimmick, if people had actually purchased them on their own, or a little bit of both.

You’ve described Dan Robbins as this seminal figure, but were there others with high reputations? Anyone who was regarded as the Picasso of paint by numbers?

Adam Grant, the first artist that Robbins hired, was a Polish émigré and a Holocaust survivor who had been spared in the camps for being the camp artist. As a concentration camp artist, Grant was asked to draw portraits of the camp commanders, a fruit still life on the wall of the prison dining room, and birthday cards and valentines for the Nazi officers. Grant actually wasn’t Jewish, he was Catholic. He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. After the war, Grant came to Detroit. He quit his assembly line job at Ford when Robbins hired him.

The thought of this Holocaust survivor creating these banal, iconic scenes during the Cold War period is surreal.

Well, wait a second. If you look at what Grant did, how much people loved his designs, it’s really quite amazing. His paint by number masterwork was replicating The Last Supper, which for him, a Polish Catholic survivor of a Nazi concentration camp—as well as for the people who paint it—was a quasi-religious experience.

I heard that Grant’s Last Supper is still in production. They tried to pull it off the market a few years ago but there was such an outcry that it was reinstated.

It’s the all-time most popular subject. Grant was the lead artist at Palmer Paint and stuck with it the longest, even after the business changed hands. People who saw him work talk about how much skill is actually required. The artist can specify their color set but each color has to be reused to make the picture come out just right. Other employees were just inkers—the drawers of detailed lines and numbers. Palmer Paint employed about 35 artists at one time, half of whom were painting compositions, while the other half were breaking them down. Another group of some 30 artists created “personal portrait” kits from snapshots supplied by customers.

Were they art school graduates?

That was true of Peggy Grant (who married Adam Grant), a woman from Baltimore who answered a classified ad she saw in the New York Times. If you were an artist, this was one way to make a living.

You describe in your book how Palmer Paint did some casual market research that shaped Klein’s marketing scheme. Is this how the paint by numbers subjects were ultimately chosen?

On that question we just have anecdotal information. Robbins initially thought that adults would be interested in painting an abstract still life. He designed Abstract #1 and showed it to Klein who said, “I hate it, but I love the idea.” So Robbins came back with a landscape and that’s where it took off.

Kittens, puppies, and horses—these subject ideas came from customers. This was Klein’s genius: each kit included a customer comment card. Customers filled out and sent in these cards with their requests. Keyed advertisements had been used before—these were small ads urging readers to clip and send in for something free that were coded to indicate the publication in which the ad appeared—but Klein’s customer comments cards functioned as a true consumer feedback device. Eventually, Palmer Paint expanded the comment card into a four-color pamphlet that doubled as a catalogue.

Of course, the legacy of paint by numbers is the business of building tools for predictive modeling of consumer reception, whether it’s a Nielsen box cranking out consumer viewing habits or focus group testing. These days, a sample audience has been built and tested for just about everything. This has been around at some level throughout the 20th century but has really come to the fore in our contemporary culture. In part, my exhibit was about investigating the evolution of these predictive modeling techniques. If the show had been larger I would have included Nielsen boxes. The story of paint by numbers’ marketing reflects the struggle to figure out what people want—what they like to look at, what they like to think about, what they like to do—and to create a formula for prediction.

Was there something in the subject matter—the kittens, puppies, and horses—that corroborated cultural critics’ charges that paint by numbers were not art? I’m curious about the relationship between Abstract Expressionism and paint by numbers. It seems that simultaneously you have these two sides, if you can call them that, both pointing to each other and saying, “That’s not art!”

You can read this in a number of ways, but I think the most telling example is the failure of abstract subject matter as a popular line. Anyone, perhaps like Robbins, or perhaps like you, who would be interested in having Abstract #1 as a composition, really isn’t going to do a paint by number. On the other hand, someone who would want to do a paint by number would perhaps rather paint a landscape or a still life with a banjo, a bird, and a cup. That’s what Klein sensed when he initially rejected Robbins’s Abstract #1. Later, of course, Abstract #1 was thrown back into the line; occasionally you find them around. At a thrift store, I found an Abstract #1 in the frame, beautifully completed, sitting right next to one of those paint by number rolling seascapes. True, the seascape was much bigger, but the store had priced the representational painting at $25 and the abstract at $1.95.

Were nudes a requested subject? Was there a subgenre of paint by number pornography?

Well, porn is in the eye of the beholder. Still life nude scenes were quite popular designs. They were advertised in the catalogue by a blank frame and a number.

Your book argues that the target consumer was an adult, but you also mention that there were kits designed to correspond to the abilities or sensibilities of different family members. The Deluxe Craft Master, for example, was geared toward the mother, the mural-size canvas toward the father and simplified paint sets for the children. Were people really painting together as families, or in more isolated circumstances?

I know more about this now because of the reminiscences people have posted on the website.[1] In fact, people often talk about the memory of painting with their parents—the smell of the paints and painting together being a time when the whole family seemed happy and together. The hierarchy of kits was something Klein picked up from his marketing background at General Motors. Not unlike different car models, paint by number kits were arranged by the complexity of the canvases to suit people of different skill or patience levels.

In your book, you describe the exhibition of paint by numbers paintings in the White House during the Eisenhower administration. Could you talk a little more about that?

The museum had accessioned the Palmer Paint collection of trade materials but you couldn’t get the museum, conservative as it is, to collect the actual paintings. So, I received a little research money to contact and meet with paint by number collectors. At the end of the traveling, I made one last call to a friend in Wichita, Kansas, at the Eisenhower Library—I had some questions about Eisenhower as an amateur painter—and as I told him what I was doing, he said, “Well, you might want to know that we recently received 22 paint by numbers that were done by Eisenhower’s cabinet.” The story was that Eisenhower had an appointment secretary named Thomas E. Stephens. Stephens was a lawyer active in the Republican Party who had come to Washington. At the same time, Eisenhower had a portrait painter by the same name, Thomas E. Stephens, who painted all of the heroes of World War II. The two Stephenses had actually known each other in New York. They both lived in Greenwich Village and they used to meet to exchange misdelivered mail. For a while I thought it was just one guy and thought, “Wow, what a talented guy.”

Anyway, it was Stephens the painter who had given Eisenhower his first paint set and that’s how Eisenhower, after Churchill, became the world’s most famous amateur painter. Fast forward to 1953 or 1954. Eisenhower is painting up a storm of his own stuff and Stephens the lawyer is sitting in his West Wing office beside a portrait of Eisenhower, signed by Thomas E. Stephens. People come in and they get confused. Stephens is described as a witty guy; he has some pluck. He buys a bunch of paint by number kits and at the next cabinet meeting, he passes them around to cabinet members who are under the impression that Eisenhower himself is asking them to paint them—an impression Stephens does little to dispel. Stephens hangs the finished paintings up outside his office in the West Wing. At the time, this was the area where guests and dignitaries were received. Stephens’s gallery actually had a mixture of things in it: pictures of the president painting, the president’s actual paintings, a watercolor portrait of a black child by [US diplomat, playwright, politician and journalist] Clare Booth Luce and the cabinet’s paint by numbers, including one by Herbert Hoover that’s lost now. People like [band leader] Fred Waring and [Broadway star] Ethel Merman would visit the White House and later send in paint by numbers to add to the gallery. Of course, the exhibition didn’t get any notice in the mainstream press.

Really? It surprises me that the press wouldn’t make an issue of it. By exhibiting paint by numbers in the White House, wasn’t Eisenhower making a stand on one side of this cultural debate between whether paint by numbers were a totally useless, mind-numbing kind of thing, or a fun way to become an artist and decorate your house?

At that time, nobody was making that kind of judgment. Not until the late 1950s does paint by numbers get caught up in cultural criticism. By the 1960s though, the critics have pronounced it to be completely worthless.

Is that why paint by numbers began to decline as an art form? People attribute it to the rise of television but do you think it’s a more complicated story?

It’s true that there are a growing number of claims on leisure time in the late 1950s. But the decline of paint by numbers also has to do with changing cultural values; eventually, our notion of “authenticity” totally rejected this kind of allegedly assembly line, cookie-cutter activity.

When I visited your exhibit, I remember enjoying three or four paint by numbers from identical kits that each artist had modified. One person had painted a tree out and somebody else had painted in a dog. Maybe I’m putting too much on it, but do you think the notion of artists individualizing their paint by numbers is a kind of quiet dissidence?

Yes, even more so when critics express objections and the artists reply, “To hell with that. I enjoy this. I couldn’t care less what you think.” You can look at paint by numbers as a metaphor for 1950s stay-within-the-line conformity—this argument has been made over and over—but I hope to introduce a deeper look at the phenomenon, especially at these people you mention, painters who are blending, shaping, and in some cases, continuing the subject out onto the frame. By expressing preferences and making choices, these painters are taking the first steps toward art. I think you can charitably argue that in these cases it was art.

You state in your book that by “doing what art was not supposed to be one could learn what it was.” Did you truly find that there were children or teenagers who were introduced to art through paint by numbers and eventually “progressed” to less didactic forms?

What paint by numbers did, it often did it in quite unanticipated, unexpected ways. First of all, it democratized art supplies. If you were a little kid in a small town in Alabama someplace, you may have never seen anything like this before, but all of a sudden you had twelve colors of paint and a brush. For $2.50 (which was still an exorbitant amount of money for some), people of rather modest circumstances could have access to the apparatus of art. The reminiscences on the website really confirm this; there was one story from a woman that especially touched me. As a child, she wanted to paint a picture for her grandparents’ anniversary. She begged her drug- and alcohol-dependent parents for the money to go to the store and finally walked to the store alone to buy the kit. But she was too young to know anything about tax, so then she had to walk back home and beg her parents for the extra pennies. First they refused, but they finally grudgingly handed her the pennies and she went back to the store and bought the paint by number. Then she read the instructions and learned that you needed linseed oil to keep the paints from drying out. Her parents refused to give her more money but without linseed oil, try as she might, she barely got the picture completed. To finish it, she resorted to gluing the dried up paint fragments onto the picture. Can you imagine that? And the whole time her parents are saying things like, “You’re worthless,” that kind of thing. When she finished, she wrapped it up, gave it to her grandparents, and they proudly displayed it. Now she’s an artist. To me, that story’s the most illustrative of what the meaning of this stuff really was. It exposed people to something they might want to try, but was otherwise completely unavailable. This is what eluded the era’s cultural critiques, and I think it eludes most people even today.

Sasha Archibald is associate editor of Cabinet.

William L. Bird Jr. is a historian and curator at the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, where in 2001 he organized an exhibition on paint by numbers on which his book is based.

David Serlin is an assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of California, San Diego, and an editor-at-large for Cabinet. He is the author of Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America (University of Chicago Press, 2004).