A Wing and a Prayer

Pigeons and the history of battlefield communication

Tom Vanderbilt

One morning not long ago as I sat in New York’s Bryant Park, savoring the first searching wisps of spring, I spied a man with a large bird perched on his shoulder, tethered to his wrist. He was, I was to later learn, a falconer from upstate New York; his charge, a Harris hawk named Starbuck, was being employed as a tentative measure to reduce the number of Columba livia that were gathering in the park to the dismay of its many noonday congregants.

I could not linger to witness nature, red in tooth and claw, enact its dramas on this metropolitan stage. Bryant Park is one of the most rigorously managed outdoor public spaces in the world, with daily pedestrian tallies, thus this attempt to restrict the avian “user mix” of the park through hawkish annexation should have come as little surprise. And pigeons, nestled as they are at the tail-end of urban bird sighting desirability—ubiquitous, ever flocking and scuttling at one’s feet, defacing building facades, these fallen forebears of noble racing pigeons perceived as winged harbingers of the city’s very filth and claustrophobic mania—who, who apart from some popcorn-distributing superannuated park denizen tinkering with the food chain, could mourn pigeons?

Let us, however, go to another city, another time. Paris, the autumn of 1870. A city under siege. With Napoleon III fallen at Sédan on September 2nd, a mere month and a half following the commencement of the Franco-Prussian war, Paris was encircled. Civic strangulation ensued: supply conduits, railway lines, and telegraph wires were choked. The initial nervous brio of life during wartime yielded to grim resignation, the capital of gastronomy reduced to a diet of cats and rats. Paris was brutally severed from anything beyond, turning in on itself. As one Parisian described it, “We were absolutely cut off from the world, not knowing what they did in the provinces, whether or not they were coming to our aid, abandoned by the universe, deprived of all spiritual consolation, reduced to the most frightful extremities. All that was nothing besides this anguish, this waiting ever deceived.”[1]

Paris, being a city of what historian John Fisher calls a “turbulent, Zola-esque, Verne-esque modernity—the gas-lamps, the bridges, the railways and the iron-clads; Baron Haussmann’s boulevards and the de Lesseps’ canal,” had a cunning response to its isolation: The balloon. The nascent field of aeronautics, led by the brothers Montgolfier, had been a French invention. Now balloons, launching from the Solferino Tower in Montmartre, offered a rather invincible medium of communication, sailing over and out of reach of the Prussian lines, whose officers included, ironically, Captain Count von Zeppelin and Lieutenant Paul von Hindenburg.

Balloons, however, offered only one-way delivery. The vicissitudes of winds and the proximity of Prussian forces made pinpoint navigation back into Paris nearly impossible. The first method of return mail to Paris entailed floating zinc balls down the Seine. None were found until well after the siege, and indeed as late as 1954 they were being retrieved from the river. And so this paragon of 19th-century modernity turned to an ancient method of communication: les pigeons voyageurs. Pigeons carried via balloons to Tours and other free French outposts could then be outfitted with messages and sent back to their Parisian lofts.

The “pigeon post” was a hoary medium: Pliny had written how Hirtius, the Roman Consul, had employed pigeons to send messages to Deciumus Brutus, surrounded in Modena. “Of what use were all the efforts of the enemy when Brutus had his couriers in the air,” Pliny declared. It is said that the caliphs of 13th-century Syria and Egypt created an entire institutionalized pigeon post, with a central citadel in Cairo and a bureaucratic department for establishing pigeon lineage. Towers housing dovecotes stretched from Cairo to Damascus, and penalties were set on pigeon killing, while bounties were placed on potential birds of prey. By 1572, the pigeon post had been exported to Europe and was used in Holland during the Spanish invasion. By the 19th century, messenger pigeons, as well as the sport of pigeon racing, were the national obsession of Belgium.

In besieged Paris, inspired by the petitions of the burgeoning pigeon clubs, the experimental means of communication was normalized as a “special interchange of correspondence.” A decree was issued: “Every person residing within the republic is permitted to correspond with Paris by means of the messenger pigeons belonging to the Administration of Telegraphs and Posts, the charge being 50 centimes a word.” (the maximum was 20 words). By November 16th, the service has been extended to England. “Pigeongrams” were announced by the London Post Office, with several restrictions: “The letters must be written entirely in French, in clear, intelligible language. They must relate solely to private affairs and no political allusion or reference to the war will be permitted.”[2]

The birds that made it to Tours were returned via train, typically to Blois—some 100 miles from Paris—and released. Estimates vary wildly, but the most widely cited note that 363 pigeons were transported from Paris during the siege, with some 200 returned; of these, about 73 returned with messages. There were many hazards, including the winter weather and the tactics of the Prussians, themselves accomplished in the arts of martial pigeonry, who reputedly employed hawks to intercept the pigeons (it is said that one Parisian boffin proposed equipping pigeons with whistles to scare away their predator). Like all forms of communication, the pigeon post was subject to the duplicity of espionage. In one episode, several pigeons that had been captured by the Prussians, along with the fallen balloon the Daguerre, were returned to Paris with news of false Prussian advances, “messages calculated to dismay Paris.” (One giveaway was that the messages were tied with normal thread, whereas the Parisians typically employed waxed thread).

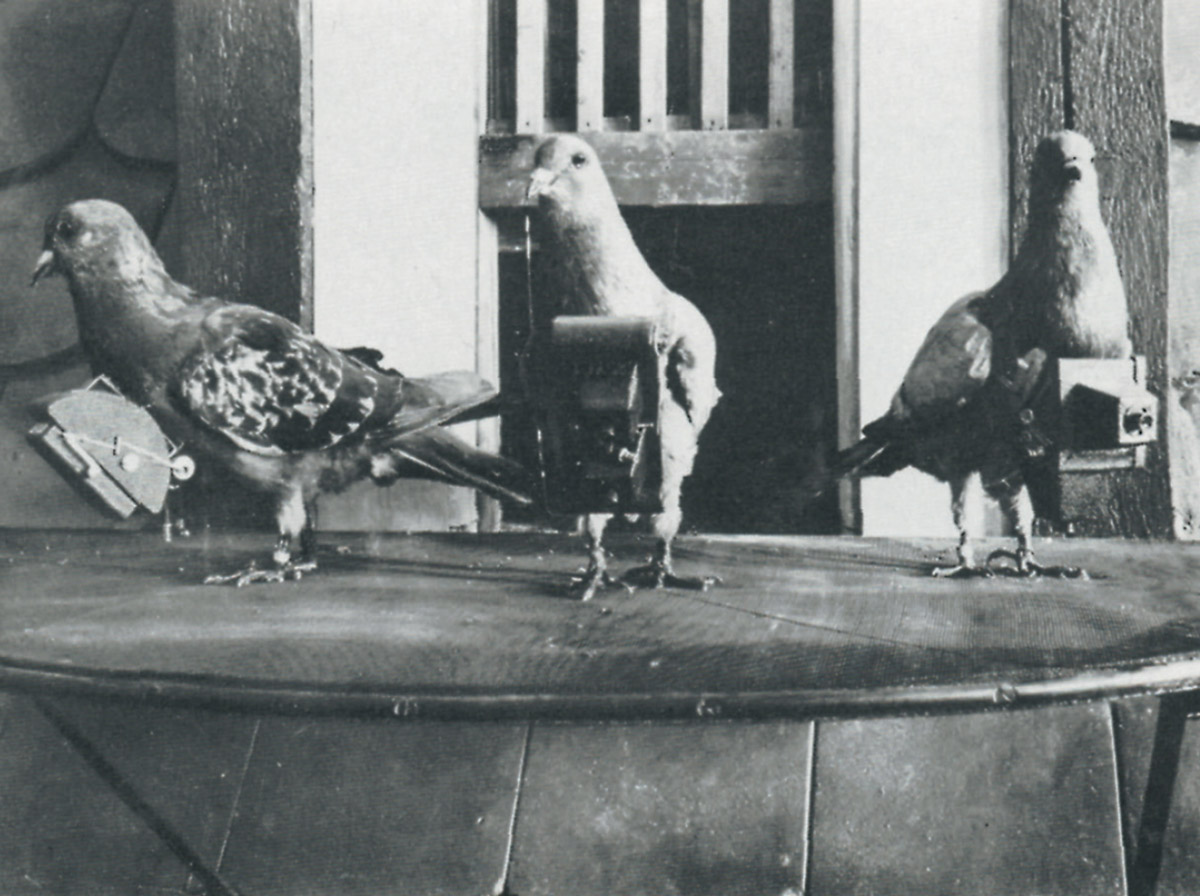

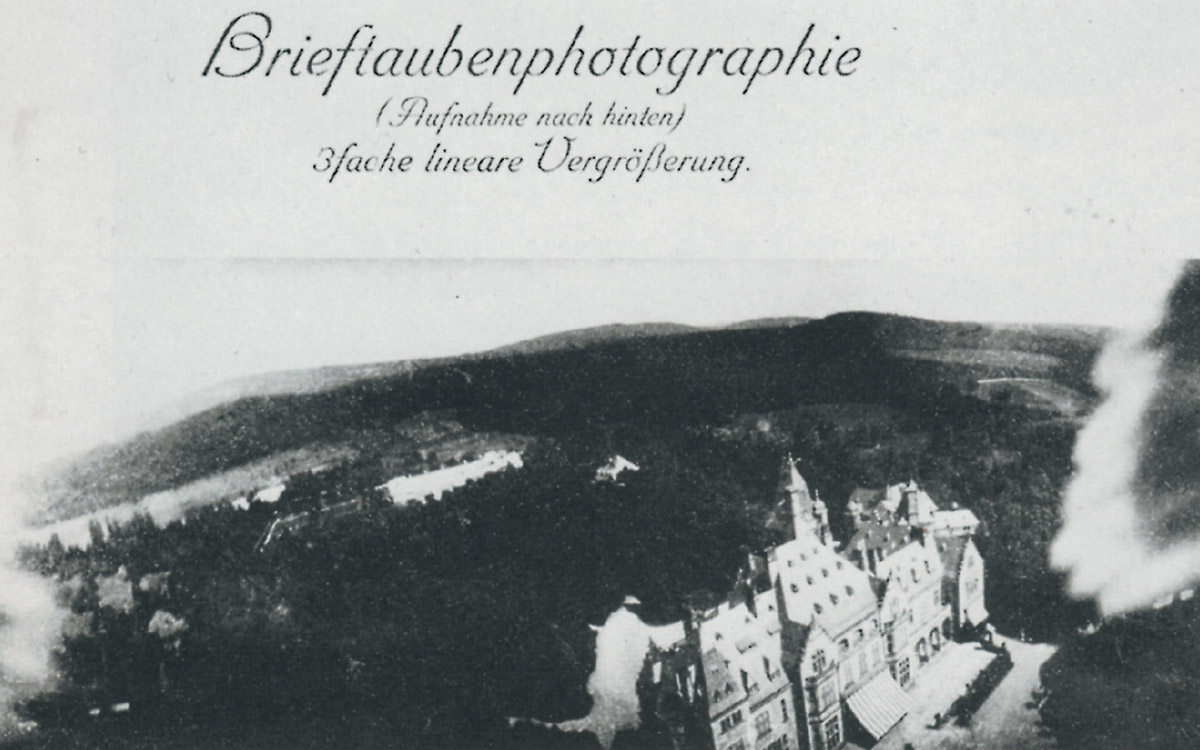

The Parisian pigeon post also marked another stunning technological advance, that of microphotography. The authorities in Tours soon realized that even the smallest conventional handwriting allowed for only a small number of messages to be returned. A Tours chemist proposed a novel solution: Writing messages on a wall in large letters, and then photographing them at a vastly reduced proportion; in Paris, the messages would be read via a kind of magic lantern. Printed on collodion membranes, several tens of thousands of messages—virtually entire books—could be freighted by a single pigeon. The system was nothing if not rigorous: every tenth bird took copies of those carried by the nine before it, and serial numbers identified the dispatches.

Despite the curtailed rate of success, the fact that the pigeons allowed any form of communication caused a sensation in Paris. Paul de Saint-Victor rhapsodized about the Pigeons of the Republic: “They are the doves of the immense ark, which the waves of fire and blood are dashing against. ... The heart of the country palpitates beneath their tender wings. How many tears and kisses, how many whispers of consolation and hope drop from their plumage, moistened by the snow or torn by the bird of prey! Paris ought to collect their broods together and shelter them beneath the roof of one of her temples. ... Their flittings in our streets and gardens would remind us of the day when the wings of a dove were dearer to us than all else.” In 1871, the London Times printed a series of entries that Léon Gambetta, the minister of the new French government headquartered at Tours who had escaped Paris via balloon, made to Parisians: “Pigeons are our only mode of correspondence with you; by letting them leave Paris in the hands of people to whom they are said to belong, you would deprive us of our so necessary communications, and you expose yourselves to receiving false news. Please remember that we never have enough pigeons. ... It is urgent that you seize all the available pigeons in Paris, so that not one shall remain at the disposal of private persons.” The pigeon had been nationalized.

Following the siege, the pigeon was to be lionized in a series of commemorative stamps, as well as in Auguste Bartholdi’s monument to aeronauts at Porte des Ternes (no word if this serves as a roost for pigeons today). The siege of 1870–1871, however, hardly marked the last use of pigeons for communication, during war or peace. An 1886 account in the magazine The Century remarks on the myriad uses of pigeons in America:

“And even the New York brokers promise to follow the example of Mr. A. De Cordova, who says, ‘I use my birds to bring the reports from Wall street to me at Chetolah, my summer residence near North Branch.’

Mr. R. D. Hume of Fruit Vale, California, claims to use pigeons with complete success between his factories, some three hundred miles to the north. Years ago certain of the Wells-Fargo agents in the mountains of Nevada used pigeons to bring them the news from the nearest station the same day, that by regular means would not have reached them until the third following.”[3]

In 1891, the New York Times observed a dawning in military affairs: “News comes from England that the British admiralty have at last awakened to the necessity for using homing pigeons as carriers of messages, and experiments on a massive scale are about to be conducted.” By World War I, all the great powers had their own pigeon corps; an account from 28 October 1916 notes that “a German carrier pigeon was captured by the French at Fort de Douaumont during the fighting in the region of Verdun on Tuesday.” The American pigeon “Cher Ami,” which carried news of the whereabouts of stranded soldiers from the 77th “Liberty” division back to HQ despite having taking an enemy bullet, was commemorated and is today displayed in the Smithsonian. Pigeons, of course, do not choose sides in war. In England, two years prior, a pigeon service carrying compromising messages from British “neutrals” to Germany had been discovered on the North Sea coast. On 16 November 1914, The New York Times reported “The bird shot at Framlingham, a short way inland from the Suffolk coast, on Tuesday has been definitely identified as a foreign pigeon, and the police are following up information which has come into their hands.” To counter the German pigeons, which bore the earmark of noted pigeon fancier Heinrich Himmler, British MI5 countered with their own falcon brigade. The intelligence service reported an action off the Cornish coast: “This was a great success. The falcon flying high above the Scillies could watch not only a part of one island, but the whole group, and any pigeon flying over them would be attacked.”[4]

As late as World War II, pigeons were still playing a significant role in war. The US Army Signal Corps, like other armed forces, had its own Pigeon Service. The birds were even deployed in seaborne planes, to aid in recovery efforts should the plane go down at sea. This raised the question of how to release a “feathered fighter” from a cockpit at 250 miles an hour. The method was thus described: “Airmen use a launching cage fitted with a device set to go off in the number of seconds it will take the cage to fall from the plane’s altitude to below 10,000 feet—the bird’s ceiling. There the cage bursts open and the pigeons come out with their wings beating. A quick wheel about to reconnoiter and to start their mysterious homing instinct working, and they settle down to the job of getting home as fast they can.”

In the same war that invented radar, the internal guidance mechanisms of pigeons were a seemingly anachronistic presence. But as the Bryant Park episode revealed, nature often offers the best design solution, particularly against itself. In the Indian state of Orissa, on the flood-prone coast of the Bay of Bengal, a police pigeon service, inaugurated in 1946, survived to the very end of the century—in fact proving invaluable during periods of severe flooding, when more modern means of communication were severed (the birds also carried post and election results). In 2000, the Belgian-bred pigeons of Orissa were finally superceded by radios, leaving the longest-running airmail service in history grounded.

- Theophile Gautier writing to Carlotta Grisi in Switzerland. All quotes taken from John Fisher, Airlift 1870: The Balloon and Pigeon Post in the Siege of Paris (London, M. Parrish, 1965), unless otherwise noted.

- J. D. Hayhurst, The Pigeon Post into Paris, 1870–1871 (Ashford: J. D. Hayhurst, 1970).

- The Century, July 1886.

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/special_report/1999/01/99/wartime_spies/263333.stm

Tom Vanderbilt is author of Survival City: Adventures Among the Ruins of Atomic America. He lives in Brooklyn.