Paper Bullets: An Interview with Herbert A. Friedman

On the history of airborne propaganda

John Peffer and Herbert A. Friedman

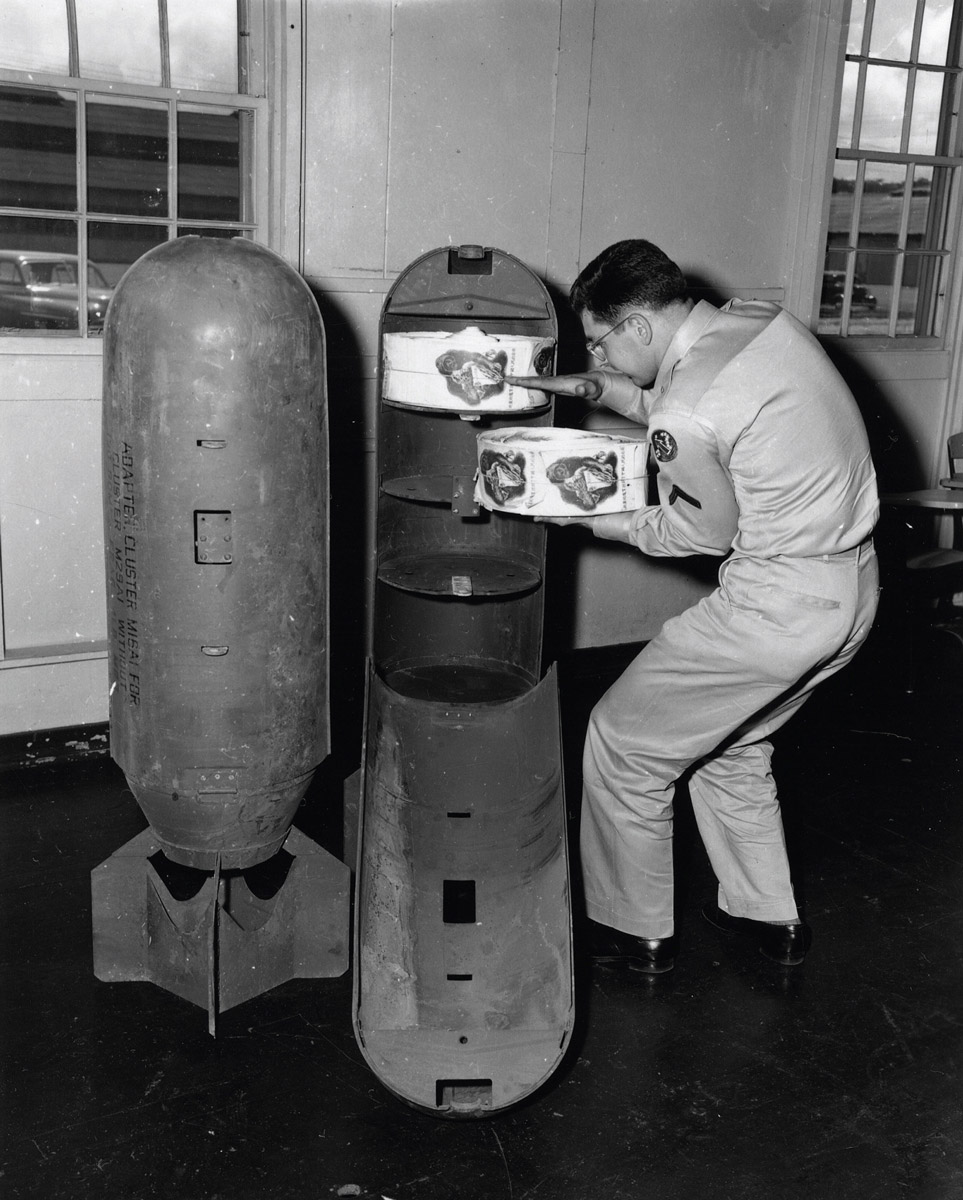

Nickels, paper bullets, falling leaves, and bullshit bombs. These are some of the nicknames given to war propaganda delivered by air in the form of printed flyers. One of the earliest recorded uses of such propaganda was in China in 1232, when kites were used to airlift notes into an enemy prison, inciting inmates to riot. During the American War of Independence, windblown leaflets were used to undermine the morale of British soldiers in Boston, and during the US Civil War messages promising money in exchange for arms and horses were floated behind Confederate lines with kites. Balloons carrying packs of leaflets, in limited use already during the Civil War, were equipped with timed fuses and employed extensively during both World Wars. In the 1960s, China and Taiwan were involved in a major propaganda balloon exchange over the Taiwan Strait, and leaflets are ballooned and fired across the DMZ in Korea on a daily basis. But it was during the World Wars that the modern form of aerial propaganda bombardment began to take shape as a critical tool of armed conflict. Bags, boxes, bombs, and missiles packed with paper messages were flown or shot into enemy territory by both the Allies and the Axis. The “Monroe Bomb” used in World War II was a paperboard cylinder adapted from a cluster-type bomb to contain several thousand leaflets. It was an early precursor of the fiberglass M-129 bomb, used in Vietnam and still today, which splits apart in mid-air over target areas.

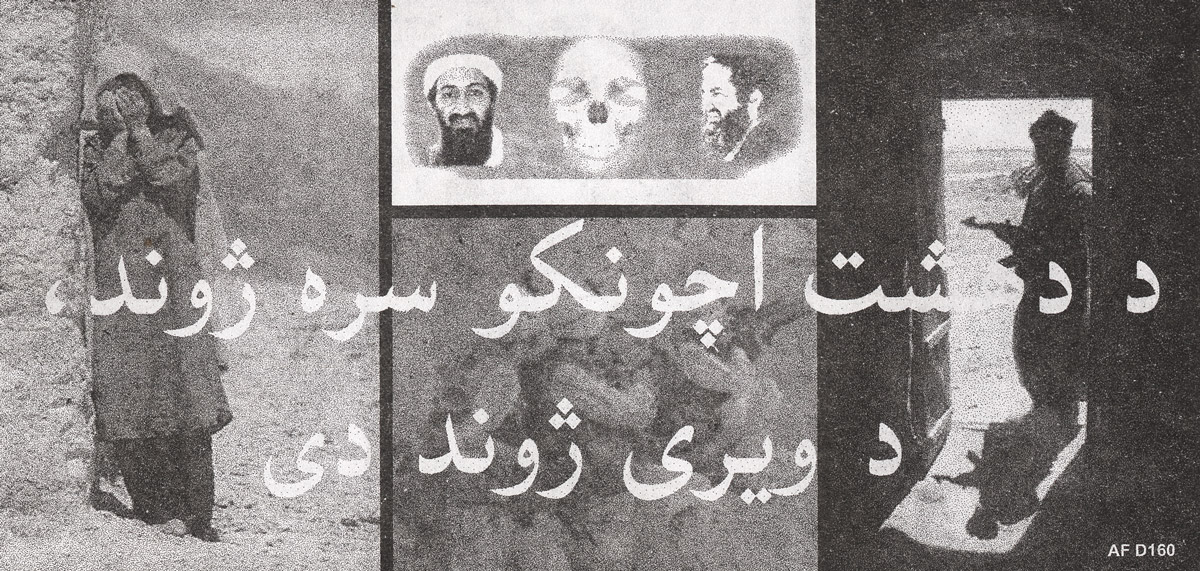

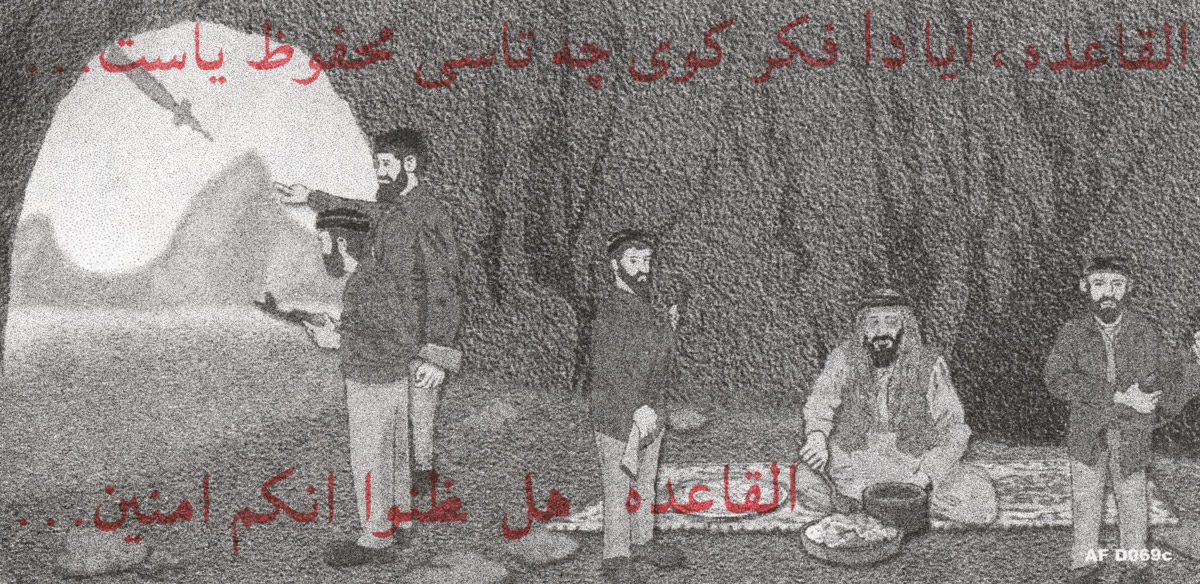

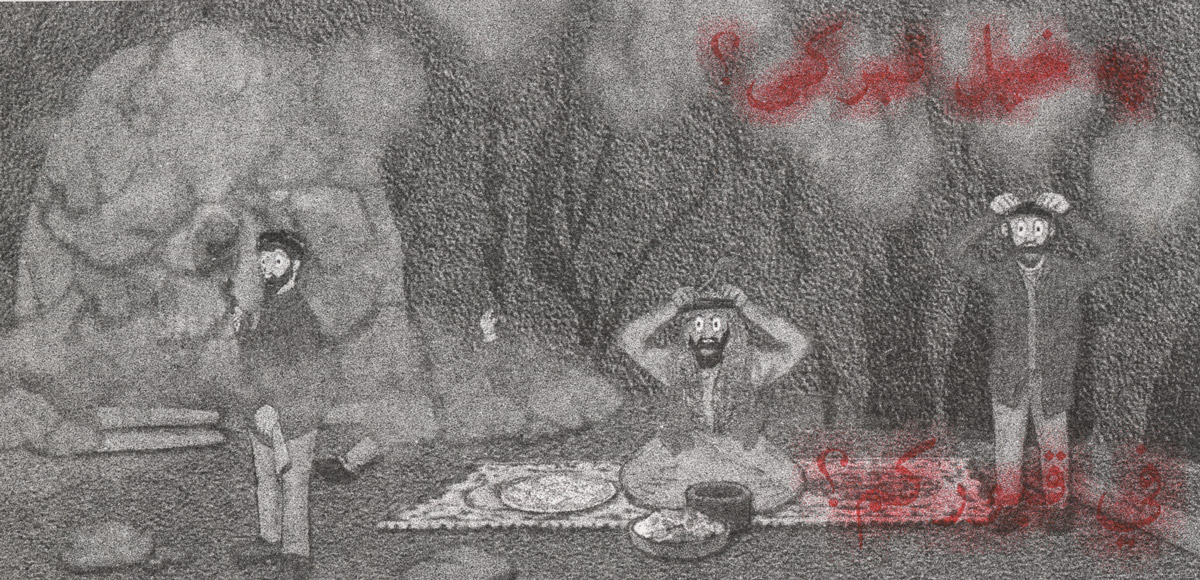

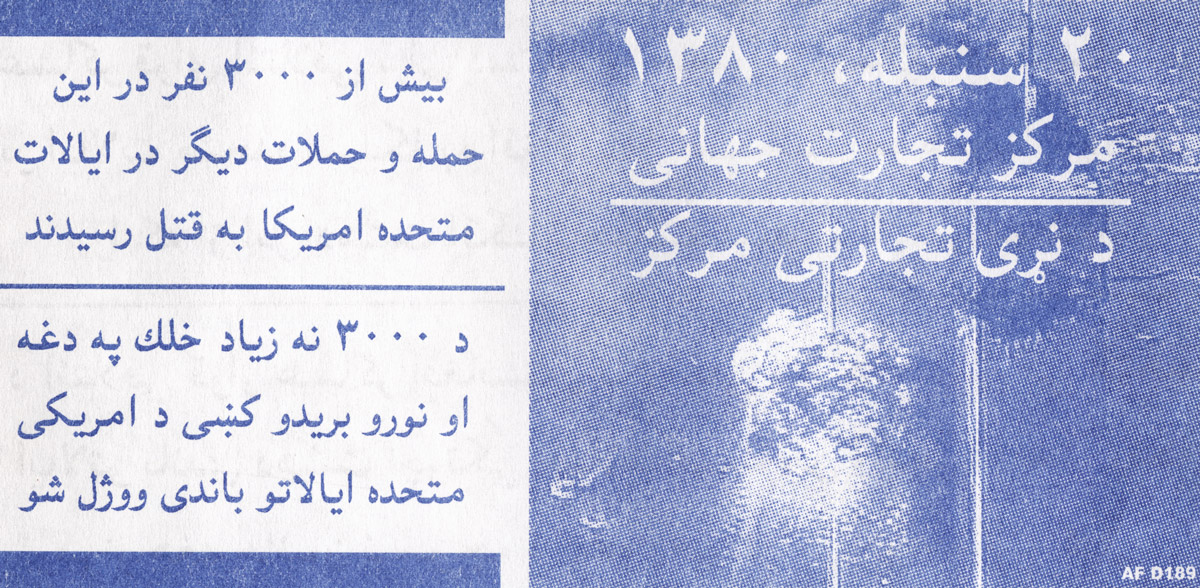

The United States Army’s 4th Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Group at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, has been responsible for designing the propaganda flyers dropped by air during the recent invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Coincident with the growing emphasis on the use of “Special Operations” soldiers and their increased public visibility in the press, the numbers of paper bombs produced during these operations have also risen dramatically. During the entire first Gulf War, the Army dropped over 29 million leaflets, of over 100 different types. Using tons of paper, the Army littered the Kuwait and Iraq landscapes with images favorable to the United States. In contrast, more than 150 million such flyers have already (by early July 2003) been designed at Fort Bragg and spread over Afghanistan and Iraq. In some ways, PSYOP resembles an advertising agency for US military objectives. They conduct marketing studies and “focus groups”—often composed of exiles and enemy prisoners of war from the target country—and carry out post-production analyses of the efficacy of their campaigns. Attention is devoted to clarity of message, given the unique cultural preferences of the intended recipients. Leaflets used in Afghanistan use green text to indicate peaceful intentions, and red lettering to indicate danger or aggression. The image of the Afghan nation in outline, or the national flag, are included to signal allegiance with collective local interests. As with the texts, written in Pashto or Dari using Arabic characters, the images in the Afghan flyers read from right to left. In Iraq some flyers have contained plain Arabic text framed, like a formal greeting card, by a decorative border. In both conflicts, the denotation of meaning has been dominated by the detonation of propaganda bombs littering the landscape from above.

The following interview was adapted from email correspondence between John Peffer and Sergeant Major (ret.) Herbert A. Friedman, a PSYOP historian and specialist, between 23 June and 29 July 2003.

John Peffer: A friend of mine who has visited Afghanistan sent me some examples of the propaganda leaflets which have been air-dropped by the United States Army before, during, and after the official military campaign. I recently read an article of yours about PSYOP flyers dropped by United States military planes during “Operation Enduring Freedom” and I’m interested in how these types of flyers are put together. I am also fascinated by the way in which an “enemy” is constructed through propaganda without pinching the sensibilities of the local people.

Herbert A. Friedman: Understand that there are no definite answers. Things are done differently to fit the mission. Leaflets can be designed in the field or at Ft. Bragg, and sent by satellite to the front. The paper can be stock or purchased locally. The leaflets can be in color or black and white, according to how many are needed and how soon. The military is performance-oriented. The successful completion of the mission is all that counts.

There seems to be more aboveground work by the PSYOP folks in recent years. This switch to visibility intrigues me. What was once something to be embarrassed about now seems to be something to take pride in.

No. In the military magazines and newspapers (such as Military Review and Army Times) PSYOP has always been well publicized. PSYOP first came to the attention of the popular press in Panama with the loudspeakers playing music in front of the Vatican compound. Later, during the Gulf War, with the large number of Iraqi personnel surrendering and waving leaflets, the press renewed their interest in PSYOP. And once again, for some reason the reporters just got interested back about the start of the Afghan campaign and I was getting calls daily to appear on BBC, CBC, and the like. The Army changed nothing. They operated exactly as they always did. It was the press that got all excited. They had nothing to write about during the build-up to the war and this stuff filled a lot of columns.

As for things becoming more “overt” in the public’s perception, the difference has perhaps to do with different sections of government operations—for instance, between the traditional covert methods of the OSS, CIA, and NSA and the sort of massive information-generating campaign that the army conducts when it drops these flyers. Do I misunderstand a fundamental difference between the two?

The CIA still keeps quiet. There’s a vast difference between black and white propaganda. The Army practices white propaganda. The messages are clearly from the USA and truthful (insofar as they meet national objectives). Black propaganda pretends to be from others, disguises its origin, and generally is not held to high standards of truthfulness.

I presume the Afghanistan flyers picked up for me are declassified, that is, if anything air-dropped by the thousands could be “classified.”

You hit on an interesting point. During World War II, most leaflets were classified even as we dropped two to three million a night on Germany. Nobody ever explained that one to me. The present leaflets are classified very low until dropped, and then they are more or less public property.

Many of the ones I have are the same as those you have published online, but are much cheaper in appearance, mostly in black and white, and in some cases hard to read. Is it possible that they were run on local presses?

Yes. Without getting specific, we can produce anywhere from two to four times the number of leaflets in black and white on speed presses than we can using the slower color presses that require multiple runs. For the purposes of the test, everything is beautiful, well centered, in full color on high-quality paper. In reality, when we need nine million tomorrow at 0600, they will jam them through in black and white.

When printed in the field, does that mean on presses already used for local, non-Army purposes like bookmaking? Or do you mean presses transported overseas by US forces?

The PSYOP companies have mobile presses and can produce product in the field. Production is also done at sea, on aircraft carriers. They can also take over and occupy, or contract, a local printing firm to produce product. It all depends on many different things; time, money, material, and the need to support the local economy all come into play.

Some of the Afghanistan flyers have a kind of chintzy fantasy look to them, similar to my eye to the posters of “martyrs” used in Palestine and elsewhere—the same garish color combinations, the same awkward Photoshop montages. Others look cartoonish, as if imitating a video game or an episode of South Park. Are these intentional aesthetics, or are they the product of either the software or the on-the-spot method of desktop publishing used in the field?

If we are dealing with a Third World nation with illiteracy, there is no point in going to great pains to produce a first-rate leaflet. Not that this applies, but in Bosnia we dropped leaflets showing big food crates coming down in parachutes and begged them to not stand under the crates (as had happened in Somalia, causing a few deaths). The other answer is that with all the fancy computer software around these days we no longer need to use real artists. Most of the drawings are computer-generated images. You lose a lot when you go CGI.

Are there no professional artists on staff to produce these kinds of flyers?

There are no absolutes. A fellow joining the military with an artistic background would be a prime candidate for PSYOP. With all the programs available now, it is far more likely that the images will be computer-drawn rather than hand-drawn. What you lose in beauty and technique you gain in speed.

Do you have any personal favorites, in aesthetic or practical terms, from the era of hand-drawn propaganda?

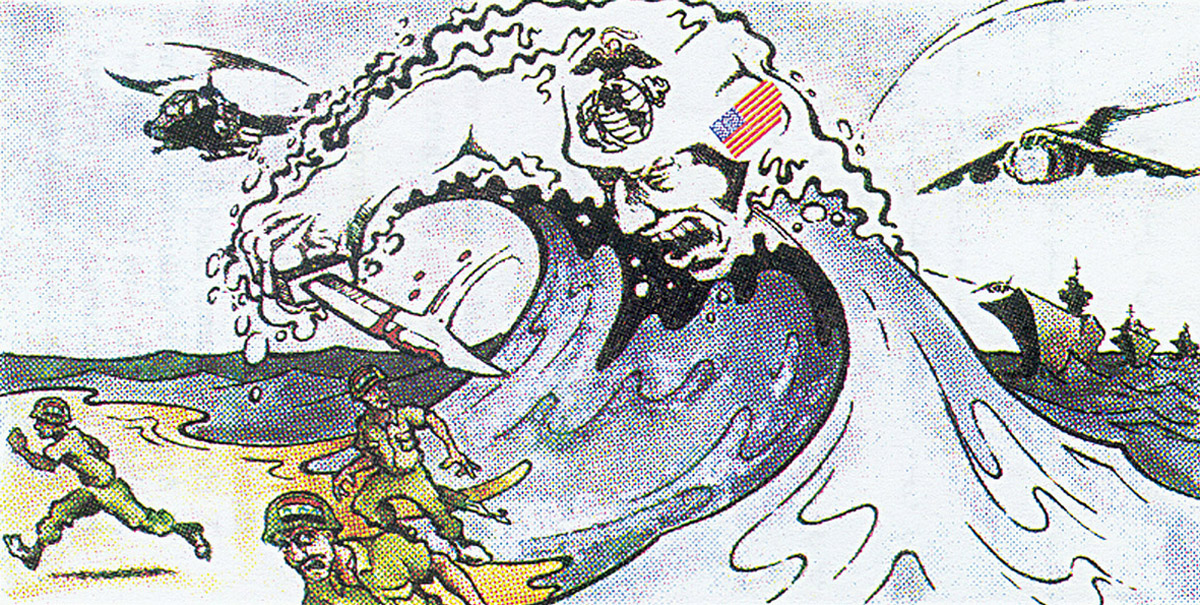

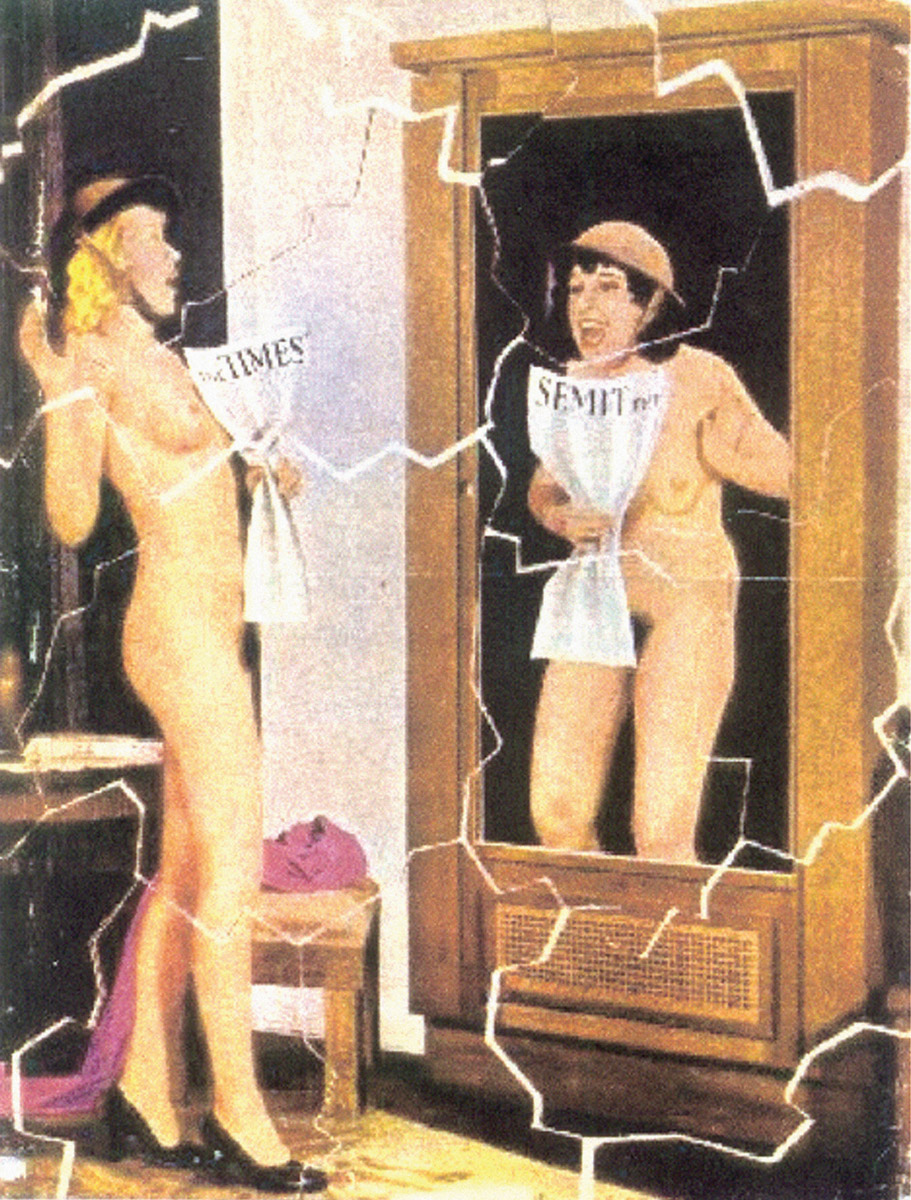

I love the German leaflet in my sex article that shows a British woman looking into the mirror while holding the “Times”; she sees her reflection inverted as a Jewish woman holding the “semiT.” It is a great piece of propaganda. I like the two Arabs walking into the moonlight from Desert Storm, and also the Marine in the waves. A great disinformation leaflet.

Some flyers have the look of money, especially the ones which offer rewards for captured enemies.

Money falling from the sky, or money on the ground, gets attention whether out of greed or just basic curiosity. People are going to pick it up to check it out. I have written about a dozen technical articles for the International Banknote Society on this very subject. Some of the banknotes were excellent. They were so good that the natives of Vietnam, for instance, used them as counterfeits. As a result, these days we “blur” them a little to make them less spendable. We produce both forgeries and parodies. The parodies are not supposed to fool the enemy or attack the economy, because if we prepare them too well they do just that, leading to us being branded a criminal nation as we were by the North Vietnamese.

Most leaflets I have seen have the flat dimensions of paper currency, even if they don’t mimic money in their imagery. Is this intentional? Are these the standard dimensions for flyers—the shape and size of dollar bills—or are there others?

There are mathematical formulas that determine how a leaflet will fall and drift according to size and weight. Leaflets can be any size. Production costs come into it when the paper buyer has to get the most leaflets out of a standard ream. (It is always about money.) These days, for the most part—I hate generalizations—the standard US leaflet is about 3 × 6 inches. In Afghanistan we did drop stationery-sized leaflets showing Mullah Omar and a banknote about three times the normal size.

Do the makers of these flyers take into consideration the look of local propaganda when they produce pro-US images for that foreign “market?”

Yes and no. We use PhDs and native citizens to design many of the leaflets. We still occasionally err. In Iraq in 1991 we showed the soldiers thinking within those little bubbles that we use in comic books. In Iraq that had no meaning. Ditto the ace of spades in Vietnam. No meaning to the locals.

You have mentioned in your writing that there was some resistance to gory depictions of war casualties in Iraq, and possibly even Afghanistan—that maybe such flyers backfired.

I have often heard verbally that such images did not work and should not be used. However, when I started checking my references for a recent article, I could find no prohibitions against such propaganda in writing. In both Vietnam and the Arab countries we were told that brotherhood was the best PSYOP. We are all (Vietnamese, Arabs, etc.) brothers and must live together in peace once the war is over. The idea is that showing dead and disfigured bodies seems to be “bragging” by the bullies, and is certainly not brotherly.

I notice that no flyers from the Gulf War use the most horrific images, such as bomb victims burned to a crisp in their cars. There are ones that show an iconic outline of the feared BLU-82 “daisy cutter” bomb, but not what it did on the ground.

Interesting. Along the highway of death there were numerous Iraqi bodies melted in the seats of their stolen limos, hands still grasping the steering wheel. Again, we had people like Colin Powell worried about the public relations of such photos if published. Most of the GIs had such photos, but few made the magazines.

Perhaps these “Death and Disfigurement” flyers, in their way, play hide-and-seek with really gory war violence, by referring to it figuratively but avoiding too-graphic depictions.

I suspect you are dead wrong here. The idea of the D&D leaflet is to show the enemy soldier (not necessarily the civilian) the horror of battle and motivate him to desert. We did not want to hide it. We wanted to shout it from the rooftops. Again, most of these were classified at the time so the average citizen had no idea what was being dropped on the enemy. In the past the public had little knowledge of what was printed. Now that we are more open, there was really only one leaflet that showed dead bodies in this latest war. In Vietnam there were dozens.

Back to my earlier question: It seems that some marketing research is done to determine the effectiveness before and after flyer drops. How is this done? Are the kinds of flyers posted by the opposition taken into consideration, in a sort of dialogue?

Interviews. POWs are routinely questioned. Have they seen a leaflet? Did they use it? What did they think of it? What was their first impression, etc. No enemy in recent wars has been able to use flyers against us. We own the sky. It is death to take to the air. The flyers we found were either captured in bunkers, or hand-carried from person to person. In general, they are laughable.

How are the US flyers distributed? Is there some kind of “cluster bomb” that is retrofitted, so that the many individual bomblets are replaced by paper leaflets? Or are they handed out on the ground?

Yes and yes. We have plastic bombs that split open to drop the leaflets. We have experimental pods that hold the leaflets in racks and fire them out pneumatically. We have artillery shells that hold leaflets. And, of course, we hand them out to the locals.

Don’t the locals simply laugh at these things and toss them over their shoulders?

Maybe. Arthur “Bomber” Harris said during World War II that all we did with our leaflets was supply Europe with toilet paper for 100 years. However, if you are handing out $5 million reward leaflets, or warning the locals that they will be shot after midnight curfew, they will probably read the leaflets carefully.

Do you think propaganda by air has been successful so far in the recent wars?

We feared CBR [chemical, biological, radiological] attacks. Numerous leaflets warned against using those agents. None were used. Coincidence? Probably, but can you prove it? We wanted those oil wells intact to support the economy of Iraq and possibly help pay for the cost of the war. We dropped numerous leaflets telling them not to destroy the wells. They were mostly captured intact. Coincidence? We told the generals not to support the regime. They didn’t. See what I mean? We can never prove that the leaflets were important, but they were used for specific purposes that the public is often not even aware of. Every report I ever read said that it is impossible to determine success. Was it the bombs or the paper? Desert Storm: 100 hours. Baghdad: 21 days. I think we can assume some success.

Herbert A. Friedman is a psychological operations historian and specialist. A member of the Psychological Operations Veterans Association (POVA) and the Psychological Operations Association (POA), he has been the psychological operations history editor of the POA’s journal Perspectives since 1990. He has written over a hundred articles on the subject of psychological operations.

John Peffer is visiting assistant professor of art history at Northwestern University.