Rock Books

Richard Sharpe Shaver’s lapidary fantasies

Brian Tucker

Richard Sharpe Shaver (1907–1975) was a Pennsylvania-born author, artist, and theorist of the secrets of human existence. He believed that a super-sophisticated civilization once thrived on Earth, eons ago, and left pictorial records of their history and lore embedded in small stones. Many of these ancient “rock books” survive today, scattered across the face of the world. According to Shaver, a rock book can be distinguished from an ordinary stone by its exterior “cover,” where vividly embossed pictures will still be visible if the wear is not too great. Rock books provide the sole available record of the true history of intelligent life on earth.

In the years just after World War II, long before he discovered rock books, Shaver gained an ardent following in response to a series of stories he had published in the pulp science-fiction magazine Amazing Stories. Shaver insisted that his tales were fundamentally true; they were presented in the guise of fiction only because the underlying reality he described was too outlandish to be published as fact by the mainstream press.

According to Shaver, human society is manipulated by a group of sadistic creatures who live inside the Earth. Known as “Dero,” these are mentally impaired descendents of Earth’s once-glorious ancient peoples. Those ancients built fabulous underground cities before they ultimately abandoned Earth in favor of a more accommodating planet. A few of them were left behind, and some of their powerful machinery remained underground as well, including the mind-controlling “ray” devices that the Dero use to project disturbing thoughts into the psyches of contemporary surface-dwellers.

Touted as “The Shaver Mystery,” Shaver’s stories provided an explanation for those who were tormented by voices or antisocial impulses. Thousands of readers wrote to verify Shaver’s claims and to attest that they had heard strange voices or encountered malevolent Dero themselves. Shaver Mystery Clubs and Shaver Mystery fanzines sprang up in a number of cities. This success soon met with opposition; a resolution was presented at the 1947 World Science Fiction Convention condemning “the Shaver Mythos and related absurdities” as “a serious threat to the mental health of many people” and a “perversion of fantasy fiction.” The controversial “Shaver Hoax” received attention in general circulation magazines, including Life and Harper’s. In response to the criticism, the publishers of Amazing Stories ended the Shaver series.

By the late 1950s, the fan clubs had disbanded and Richard S. Shaver was largely forgotten. Living in rural Wisconsin before settling finally in Summit, Arkansas, his continuing search for physical artifacts of the antediluvian civilizations led to his discovery of rock books. He postulated that the ancients had developed equipment to embed multi-dimensional imagery in stone; they also produced “penetrative light” viewing devices that would project these rock pictures into three-dimensional scenes, somewhat akin to a modern hologram. The pictorial content that Shaver identified in these rocks is dense and complex. Different images reveal themselves at every angle of view and every level of magnification; pictures mingle with ancient graphic symbols and typography in what he called “the most fascinating exhibition of virtuosity in art existent on earth.”

Frustrated that people seemed unable or unwilling to recognize the images, Shaver devoted the final decade of his life to creating visual aids for the proper understanding of rock books. Lacking the technologically advanced device needed to fully decipher the stones, Shaver improvised methods to extract at least a small part of the information packed into the rock books. He sliced the rocks with a saw to expose a cross-section of the embedded imagery; he considered this a regrettable act of mutilation that obscured or confused images even as it revealed them. “Cross-sections of Venus de Milo would be confusing even if you knew what it was,” Shaver wrote. The problem was compounded because “in the case of rock-book cross-sections, no one knows what the original looked like.”

Shaver employed a toy opaque projector to enlarge the stone patterns onto a surface where he traced the rock imagery with paint, pastels, soap flakes, wax, and dyes. Discouraged by critics who charged that the figures pictured in his paintings were mere fabrications from his own imagination, he eventually abandoned painting in favor of the relative objectivity of photographic documentation. In an unpublished manuscript, Shaver writes, “If I hadn’t been an artist most of my life, I would have realized that people will believe photos, and won’t believe drawings or paintings […] The camera wins, by being honest … which doesn’t say much for artists’ honesty, I guess. We try … but people think we lie.”

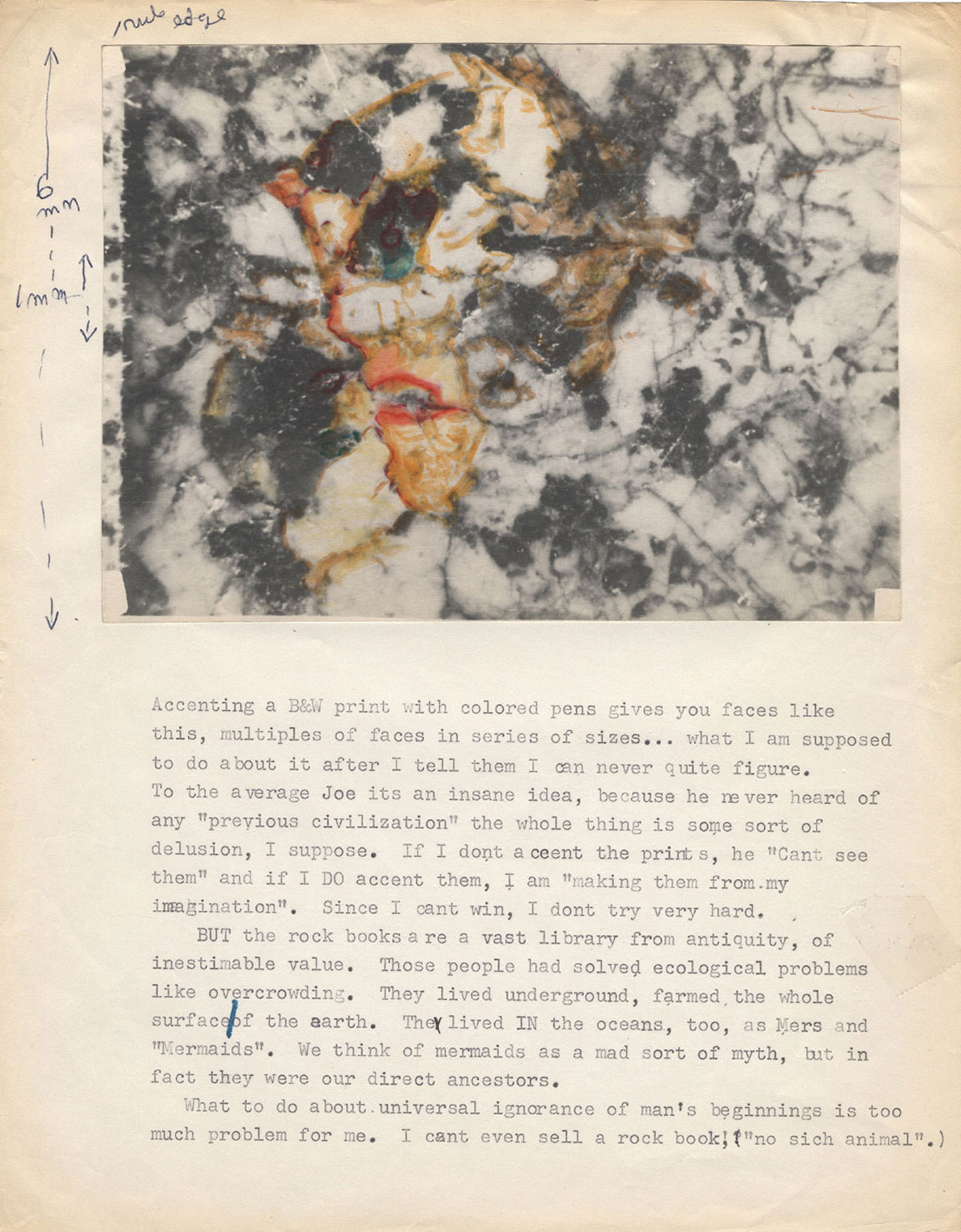

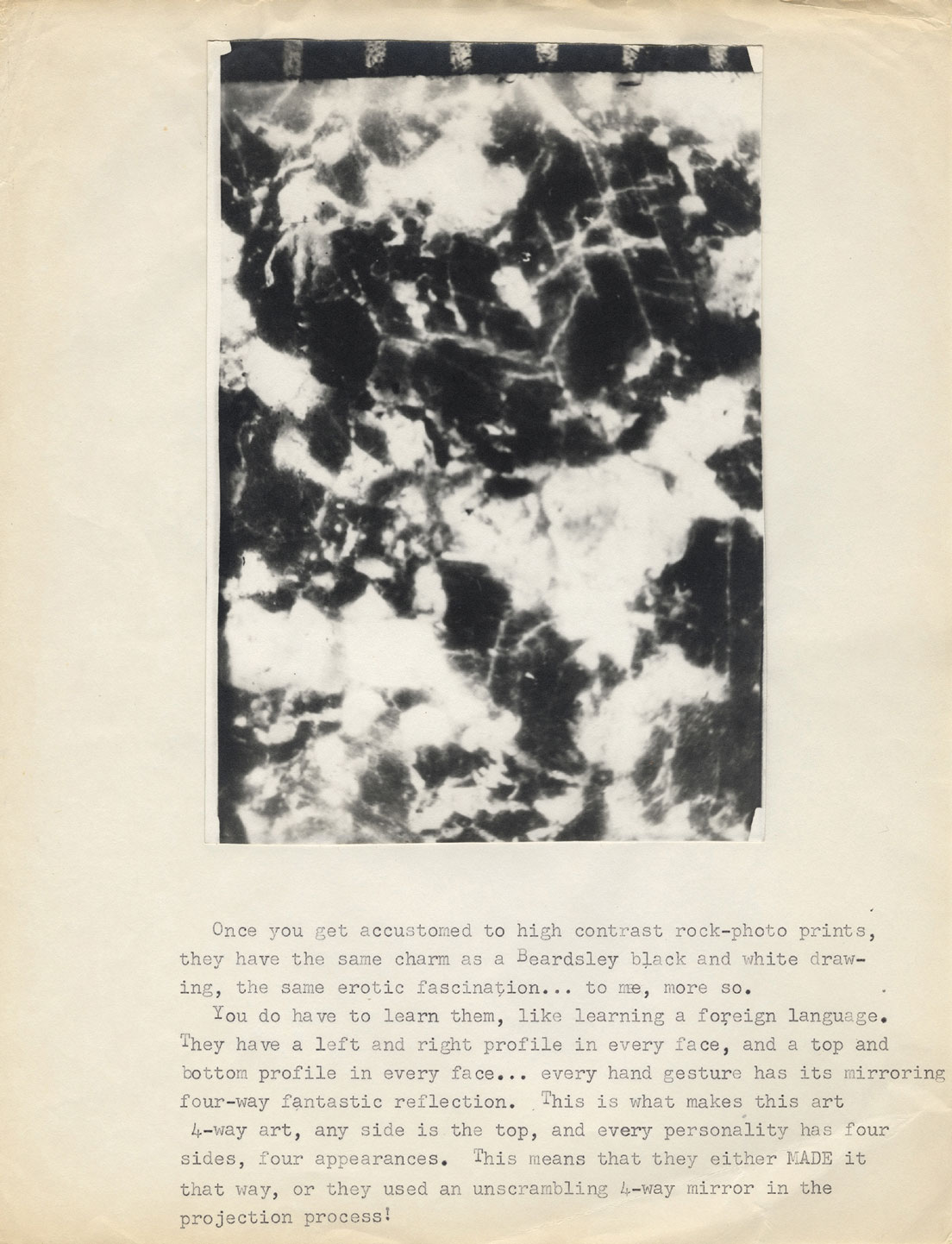

He mostly shot black-and-white photos of cross-sections of rock, occasionally highlighting details by hand-coloring the prints with felt pens. Some photos were annotated with typewritten explanations of the images, descriptions of his photo techniques, or commentary on the reception of his efforts. Few of Shaver’s pieces are precisely dated—the annotated photos reproduced with this article appear to have been made between 1967 and 1972. Despite poverty and virtually unremitting scorn, Shaver continued this work until his death in November 1975.

The Secret World by Ray Palmer (Amherst, Wisconsin: Amherst Press, 1975) includes a richly illustrated section by Richard Shaver about rock books. Information about Shaver can also be found at the online zine Shavertron (www.shavertron.com).

Brian Tucker is an artist and writer who lives in Los Angeles. His narrative exhibition about Richard S. Shaver, The Hidden World, was first presented in 1989. He is currently preparing a book about Shaver. Tucker is the former managing editor of the art journal X-Tra, and has taught in many studio art programs, most recently at the University of California, Irvine.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.