The Clinical Orgasm

A medical history of the vibrator

Rachel P. Maines

In laws that are little known and seem antiquated yet bafflingly were introduced only recently, the sale of vibrators and dildos is outlawed in Alabama, Texas, and Georgia. Owning more than five sex toys is illegal in these states because such possession indicates intent to sell. Rachel P. Maines, historian and author of The Technology of Orgasm, wrote the following affidavit in 2001 as part of an attempt by the American Civil Liberties Union to challenge Alabama’s anti-obscenity law.

In the affidavit, extracted below, Maines shows that the vibrator long ago became one of the nation’s first and most popular domestic electrical appliances. The use of the vibrator, she shows, was an essential—if misogynistic—physician’s tool for the cure of nervousness and hysteria in women.

In 2004, despite Maines’s efforts to oppose the ban, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the Constitution did not include a right to sexual privacy and the Alabama law was upheld.

Rachel Maines, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1746, hereby makes the following declaration in support of Plaintiff’s Motion for a Preliminary Injunction: Rachel Maines, Ph.D., declares and states:

Hydriatic massage technologies were available at spas that began operating in Pennsylvania in the 1760s and in Virginia in the 1770s (Fishwick 1978:17). A steam-powered vibrator was invented in 1869; the electromechanical vibrator, immediate predecessor of the devices now at issue, was invented in 1883 (Legget 1874: v.2: 912; Mortimer-Granville 1883; Snow 1912: ch.1). The vibrator became available in the United States as a consumer appliance in 1899, becoming the first personal-care electrical appliance (Hutches 1899:64e; Lifshey 1973:28 1). No Federal law has ever prohibited or restricted the sale of vibrators, and no state did so before 1973. Thus Alabama’s statute § 13A-12-200.2(a)(1) (Supp. 1998) and similar measures in other states represent a departure from a tradition that had been established more than two hundred years before its passage.

Vibrators were and are included in its oversight. Ordinary massage vibrators were made Class I devices in 1996, exempting them from pre-market notification requirements, although manufacturers must still register with the FDA (FDA CDRH Nov. 2000). Before 1996, manufacturers were required to fill out a form that asserted the device’s compliance with standards of performance (that is, that they operated as advertised), of electrical and radiation safety, and of branding and labeling (FDA 1995). The FDA has acted against misrepresentation in the advertising and labeling of vibrators, as in cases where they were promoted as effective therapies for polio and arthritis, but not against the devices themselves unless they were an electrical or radiation hazard (Lent 1904:225; US Food and Drug Administration 1963:11–23). The FDA explicitly recognizes massage of the human genitalia as a legitimate therapeutic use of vibrators, including vibrating dildos for Kegel’s exercise. Genital vibrators and vibrating dildos are Class II products for which manufacturers must complete a performance standards report on FDA form 3500A (FDA 1995; FDA 1998). The devices are listed in the FDA’s classification scheme with other technologies that do not require medical supervision or intervention for proper use, including condoms, breast pumps, and tampons (FDA 1998). Non-powered dildos are not regulated at all, and never have been, presumably because there are no electrical, fraud, or other consumer hazards associated with them. The FDA’s documentation of its policies on these devices and its record of interventions clearly indicate that its only concerns are consumer safety and protection from fraud. There is no indication of any FDA interest in regulating public morality or in restricting consumer access to vibrators or vibrating dildos through the mediation of prescriptions and/or medical supervision of their use.

Hysteria/anorgasmia was regarded as a very common disease, second only to “fevers” in its incidence, according to the famous 17th-century physician Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689). Since the common cold was medically classified as a “fever,” this made hysteria a very widespread disease indeed. As in the case of the common cold, self-treatment was common, as was treatment by alternative practitioners such as midwives. Although physicians in all historical periods have routinely grumbled about patients’ insistence on self-treatment for common and non-life-threatening ailments, no law or custom, then or now, required sufferers from hysteria/anorgasmia to seek medical guidance for treatment.

Although women suffering from hysteria and chlorosis were often directed to water-cure resorts by their physicians, it was by no means a requirement for treatment that the sufferer be under a doctor’s care (Bell 1855: 1–13; Irwin 1892:246–248). As noted above, many visitors to spas had no health excuses at all (Nicklin 1835; Fishwick 1978). Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams and mother of John Quincy Adams, spent some time at Bath in England in January 1787, enjoying two weeks of treatment in addition to what she called “amusement and dissipation” (Levin 1987:233–234). According to Adams, some women went to spas simply from “wantonness” (Levin 1987:237). Despite complaints from Protestant clergy echoing those of ancient Rome about the gambling, drinking, and general atmosphere of immorality that were thought to prevail at spas and watering places, the respectable and elite, including Thomas Jefferson and George and Martha Washington, continued to visit them (Fishwick 1978:41 and 170; Bridenbaugh 1946:160–161; Juvenal 1958:63–90).

Alabama’s hot springs were developed as resorts before the mid-19th century (Sulzby 1960:59). Before 1823, when the Cedar Hotel opened at Alabama’s Valhermoso Springs (Morgan County), most affluent valetudinarian Alabamians seeking physical therapy for hysteria and other disorders traveled north to Virginia (now West Virginia), where the hot springs over which Greenbrier now stands were already in use as a resort by 1780 (Greenbrier 2000). The “pelvic douche” was offered at nearly all of these establishments; orgasm would incur in most women after about four minutes of such treatment (Fishwick 1978: 59; Halpert 1973: 526). By the middle of the 19th century, hundreds of such spas had appeared in all parts of the country (Pond 1978: 64–73; Roark 1974: 28–38; Stone 1875: 161–171; Thorne 1970/71: 321–359; Woodlief 1954: 159–164; Irwin 1892: 85–134; McMillan 1985: 36–49.)

There was no state or federal regulation of these spas nor of their methods of treatment, until a few states and municipalities in the early 20th century took action, not to protect the morality of spa-goers, but to preserve the purity of the water that attracted this exceptionally lucrative form of health tourism (Sigerist 1942:141; Ant and McClellan 1943: 695–699; Fishwick 1978: 205).

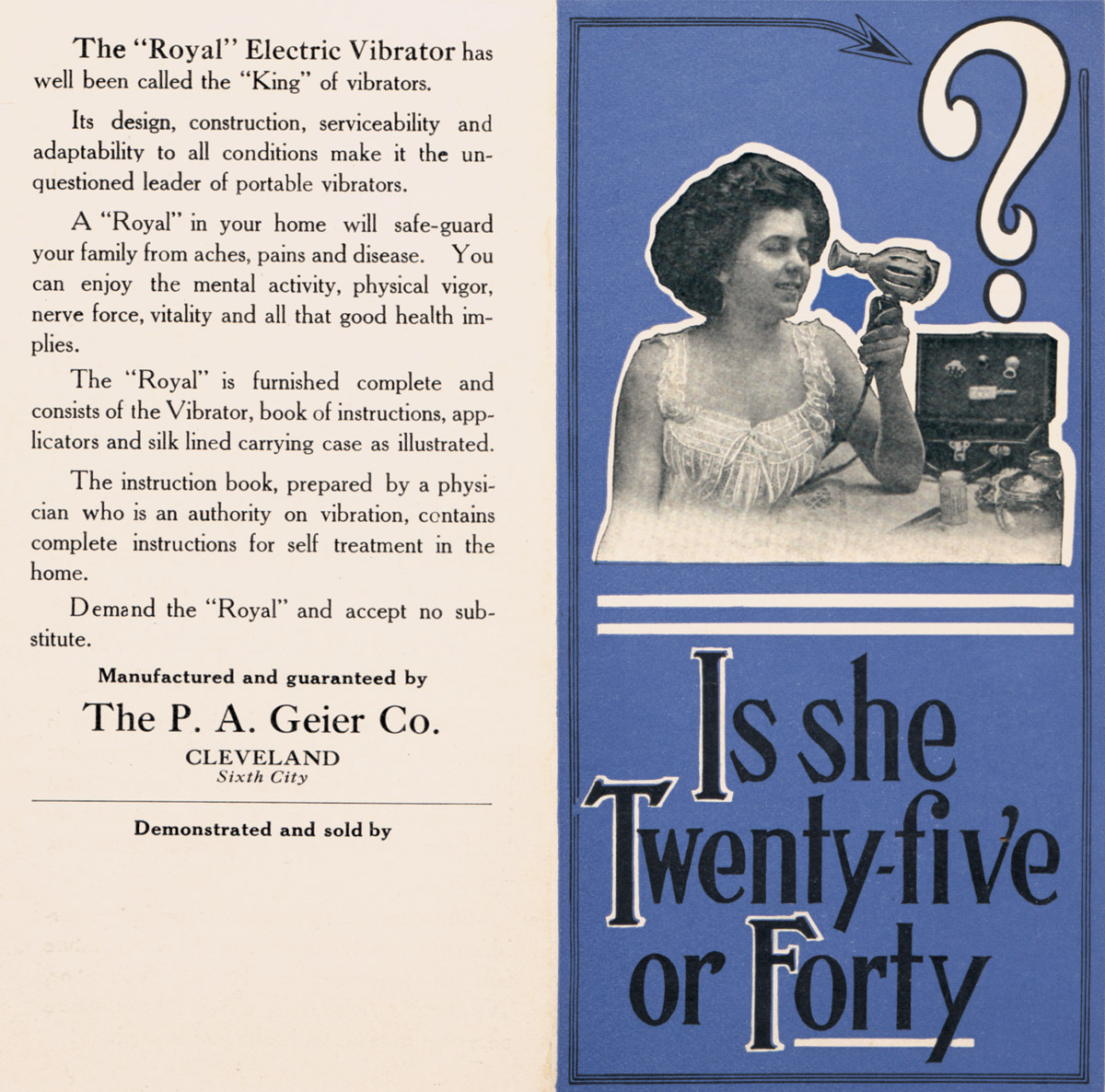

In 1899, however, a battery-powered model was introduced into the consumer market, which was soon followed by other devices marketed to consumers that used line electricity, which resemble modern vibrators. Some had dildo-shaped attachments, or “vibratodes,” as they were then called. Some of the advertising for early vibrators overtly suggested sexual uses, such as that of Lindstrom Smith, which described the action of its vibrators as “thrilling” and “penetrating,” promising that “the pleasures of youth will throb within you” (Lindstrom Smith 1908:15, 1910:27, 1913:75, 1915:45, 1916:154). These devices were marketed in household magazines and mail order catalogs until the late 1920s and early 1930s, when they began to appear in stag films and other pornographic materials, such as cabinet cards, examples of which are held in the collections of the Kinsey Institute (American Vibrator Co. 1906:42; Blake 1968:33–34 and 46; Maddocks 1916:126; Monarch Vibrator Company 1916:159; Sears, Roebuck and Co. 1918:4 and 8–9: Star Electrical Co. 1922; Swedish Vibrator Co. 1913:60). At the same period, physicians dropped the vibrator from their therapeutic armamentarium (Maines 1998:20). Vibrators remained legal throughout this period, and were mailable matter under the Comstock laws of 1873–1914. Although Anthony Comstock himself may have seized and destroyed some dildoes in his notoriously warrantless raids on retailers and manufacturers of rubber contraceptive devices, the evidence from primary sources, including cases, indicates clearly that enforcement of the Comstock laws was directed against contraceptives, abortion, and sexually oriented writings and pictures. There are no references to cases involving dildos and vibrators in either the annotations to the US Code for 18 USC 1461 or in Federal Cases (Broun 1927:92; Comstock 1967:137; Beisel 1997:158–198; Sanger 1915; D’Emilio and Freedman 1988: 156–167; and Federal Cases 1896 v.24 case 14,751:1093–1107).

In the mid-1960s, physicians and sex therapists began to recommend the use of vibrators, massagers and soft-bristle electric toothbrushes to their anorgasmic female clients (Dengrove 1971:7–8). Betty Dodson began educating the then-nascent women’s movement in the late 1960s in the importance of orgasm to female sexual health, recommending the vibrator and related technologies as a balancing influence to the androcentricity of many heterosexual relationships, a problem frequently encountered by sex therapists (A. Ellis 1963:136; Dodson 1978 and 1987; Francoeur 1982:588; Hite 1976; Kaplan 1984:34; Knox 1972:23–25; Landers 1985:85 and 132–136; Reuben 1971; Safran 1976:85–88 and 136).

Despite the apparent absurdity and tardy appearance of these legislative measures, Massachusetts retains on its books a law against the sale of “an instrument or other article intended to be used for self-abuse” (General Laws § 272-2 1), passed in 1879. The fossil character of this statute is evident both in its antiquated language and in its clauses prohibiting the sale of contraceptives, which were nullified by the Supreme Court’s decision in Griswold vs. Connecticut (1965). South Dakota included in 1968 vague warnings in its anti-obscenity act SD Code § 22-24-27 regarding unspecified “equipment, machines or materials” that might appeal “to the prurient.” The following year Kansas drafted legislation now comprising KS § 21-430 1, which in its present (amended) form prohibits the sale of “a dildo or artificial vagina, designed or marketed as useful primarily for the stimulation of human genital organs, except such devices disseminated or promoted for the purpose of medical or psychological therapy.” This Kansas statute did not withstand challenge in 1990, nor did Colorado’s Rev. Stat. § 18-7-1-101, 102, passed in 1981 and overturned in 1985. Georgia passed § 16-12-80 (c) on this question in 1975. The Texas statute § 43.2 1, passed in 1977 and upheld in 1985 and 1994, prohibits the sale of “a device designed and marketed as useful primarily for stimulation of the human genital organs,” making it an offense to possess “six or more obscene devices or [sic] identical or similar obscene articles” because such possession indicates intent to sell. In the same year, Nebraska legislated against any “article, or device having the appearance of either male or female genitals” (Nebraska Code § 28-808), clearly reacting to the appearance rather than the function of sexual devices. In 1983, two more states weighed in, Indiana with a statute (IC § 35-49-1-3) as vague as South Dakota’s and probably copied from it, and Mississippi with what was already becoming the standard wording for this new type of legislation, prohibiting the sale of any “device designed or marketed as useful primarily for the stimulation of the human genital organs” (Mississippi Code § 97-29-105). Louisiana passed LA Code § 14.106.1 in 1985, struck down as “arbitrary and capricious” in 2000, prohibiting the sale of “an artificial penis or artificial vagina, which is designed or marketed as useful primarily for the stimulation of human genital organs” [State v. Brennan 772 SO 2nd 64 (LA 2000)].

In these legislative novelties, appearance, packaging, and marketing rather than functionality seem to be the decisive factor in whether or not a device is “obscene.” Other than these, all of the states plus Guam currently define obscenity in some way that includes only media of communication such as books, pictures, and films, which vibrators and dildoes clearly are not.

Executed on April 30, 2001

Rachel P. Maines, Ph.D.

Rachel P. Maines holds a doctorate in Applied History from Carnegie-Mellon University and is a Visiting Scholar at Cornell University’s Science and Tech-nology Studies Department. She is the author of two books, The Technology of Orgasm (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999) and Asbestos and Fire (Rutgers University Press, 2005), plus a number of articles on material culture and the history of technology.