National Insecurity

A. C. Hobbs and the Great Lock Controversy of 1851

Jeffrey Kastner

I cordially concur with you in the prayer, that by God’s blessing this undertaking may conduce to the welfare of my people, and to the common interests of the human race, by encouraging the arts of peace and industry, strengthening the bonds of union among the nations of the earth, and promoting a friendly and honourable rivalry in the useful exercise of the faculties which have been conferred by a beneficent Providence for the good and the happiness of mankind.

—From Queen Victoria’s remarks at the opening of the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry of All Nations, 1 May 1851

Delivered on a fine spring afternoon before an audience of some twenty-five thousand, Victoria’s brief inaugural oration for the Great Exhibition marked the official opening of one of the grandest and most ambitious peacetime endeavors of the nineteenth century, and what was to become a watershed event in the history of the burgeoning modern age. Over the next five months, more than six million visitors would pass along the soaring allées of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace—a sunlit citadel of iron and glass erected over twenty-one acres of London’s Hyde Park—to view over one hundred thousand displays of artistic, commercial, scientific, and mechanical achievement submitted by some fourteen thousand exhibitors from Britain and her colonies, from continental Europe, and from the United States. The first “world’s fair” for a world then becoming aware of its increasingly global character, the Great Exhibition was foremost a prideful celebration of the British Empire’s cultural and industrial superiority. Yet even as it served to physicalize the host nation’s longstanding preeminence on the world stage, the exposition also offered early glimpses of its denouement. It enacted the “friendly and honourable rivalry” between Britain and her economic competitors in a broadly public context, as spectacle and even a kind of entertainment, and with the real (if generally thought to be unlikely) risk that she might be judged by that public to be inferior to her upstart rivals for technological and economic dominance.

Accounts of the day do not record whether Alfred Charles Hobbs was among the crowd assembled for the Queen’s dedication speech, but the young American locksmith would no doubt have heard in Victoria’s words an invitation to just the kind of challenge he had hoped to find on his first trip abroad. Hobbs had come to London as a representative of the New York firm of Day & Newell, which was exhibiting as part of the exposition’s American department. (Located in a prominent spot at the far western end of the building’s central nave, the US display was an elaborate affair that featured, among other things, a life-sized section of Nathaniel Rider’s new suspension truss bridge, a twelve-foot-high ziggurat fashioned from Charles Goodyear’s vulcanized India rubber, and, to serenade visitors, a grand pipe organ draped with an American flag and surmounted by an enormous sculpture of a bald eagle.) For his part, Hobbs had brought with him a more modest, if no less extraordinary artifact: his boss Robert Newell’s celebrated Parautoptic lock, a piece of machinery designed to compete with, and surpass, the security devices available at the time in Britain, generally agreed to be the finest in the world. Hobbs’s plan was not only to promote the benefits of Newell’s lock, but to do so by publicly demonstrating the insufficiency of its competitors. As it turned out, his method for accomplishing this goal became one of the most talked-about subplots in the story of the Great Exhibition.

• • •

Public excitement over the Exhibition did not abate following its grand debut and the major London newspapers dutifully covered the comings-and-goings in Hyde Park on a regular basis, and in exacting detail—announcing various daily events associated with the fair; recording the opinions of important personages; noting the arrival of visitors from abroad; and even cataloguing the contents of the Crystal Palace lost-and-found (“3 umbrella cases, 4 rings, 8 fans, 1 silver watch and guard, 1 operaglass, 2 toothpicks, 1 thimble…”). Four months into the show, the 7 September 1851 edition of the News of the World still devoted nearly five thousand words to the news from Crystal Palace, trumpeting everything from the visit of “1000 workmen from Sunderland … accompanied by the Mayor of that town,” to the arrival of an expedition of “Piedmontese artisans” come to inspect the “wonders of the Crystal Palace,” and sneeringly reporting the opening of several “packages of articles … recently arrived from India” the contents of which, “being of the rudest possible manufacture, are extremely interesting as illustrating the state of society among the hill tribes in the province of Bhangalhore.”

Near the top of the day’s digest was an item headed “The Success of the American Lockpicker,” regarding the contentious activities of none other than Mr. A. C. Hobbs of New York:

The lock controversy continues a subject of great interest at the Crystal Palace, and, indeed, is now become of general importance. We believed before the Exhibition opened that we had the best locks in the world, and among us Bramah and Chubb were reckoned quite as impregnable as Gibraltar—more so, indeed, for the key to the Mediterranean was taken by us, but none among us could penetrate into the locks and shoot the bolts of these masters. The mechanical spirit, however, is never at rest, and if it is lulled into a false state of listlessness in one branch of industry, and in one part of the world, elsewhere it springs up suddenly to admonish and reproach us with our supineness. Our descendents on the other side of the water are every now and then administering to the mother country a wholesome filial lesson upon this very text, and recently they have been “rubbing us up” with a severity which perhaps we merited for sneering at their shortcomings in the Exhibition.

That a controversy over locks would have “become of general importance” in Victorian England was more than a fluke—the mid-nineteenth century was a renaissance moment for the development of locking devices as an emerging middle class, increasingly congregated in population-dense urban areas, sought more efficient and reliable means to secure their homes and effects. In a sense, the issue of personal safekeeping was a microcosm of larger political concerns about security as well—a nation like Britain that had used its superior ingenuity to acquire vast wealth also had to be able to effectively protect it.

Though the first wooden pin locks (in which upright pegs on a toothbrush-like key lifted a set of matching pins on a simple bolt attached to the door) had appeared as early as 3000 BCE in Egypt, it was the Romans who began to use metal for lock-making, and who introduced the concept of the “warded” lock—situated around the keyhole on the interior of the lock, a series of elaborate projections, or “wards,” required a given key face to have a set of matching slots in order for it to turn freely within the housing. Pin locks and warding patterns dominated lock design up through the end of the eighteenth century, when predominantly English inventors like Robert Barron began to experiment with more complicated multiple-action tumbler locks; these used an advanced system of levers that had to be raised in their slots by the user’s key to exactly the right level for their bolts to be released.

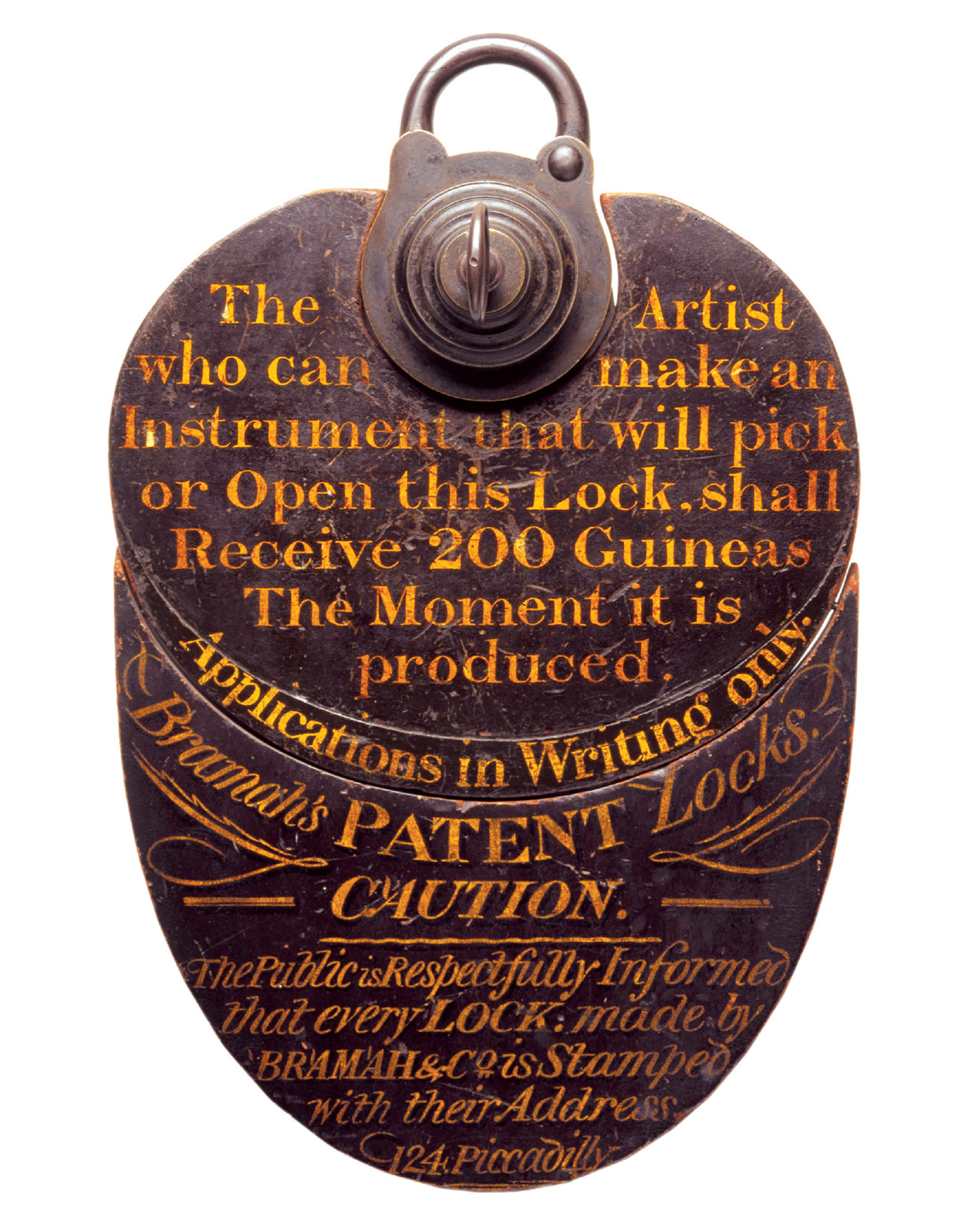

The names Bramah and Chubb hardly needed further introduction for the readers of the News—Jeremiah Chubb of Portsmouth, England, and Joseph Bramah of London were the Empire’s two most eminent lockmakers. Chubb had gained fame in 1818 for the “Detector” lock that he devised with his brother and partner, Charles, which incorporated an ingenious spring device that grabbed any tumbler lifted too high (as by a false key or lockpicker’s implement) and held it in place, simultaneously rendering the lock inoperable and preserving evidence of tampering. Meanwhile, Bramah, a successful engineer who in 1778 had patented the first flush toilet—featuring the float and valve system still used today—had turned his attention to lockmaking and with his assistant Henry Maudslay (a great engineer in his own right, whose pioneering work with machine tools was invaluable to his mentor’s work) devised an altogether different sort of device. It was circular, and featured a small tubular key whose end was incised with a series of longitudinal slots that, when inserted into the lock, depressed a configuration of slides to a set correct depth to release the bolt. The eighteen-slider lock Bramah patented in 1787 was calculated to have more than 470 million possible permutations and was widely considered unpickable. Indeed, in 1801, Bramah made a public challenge to advertise his handiwork’s impregnability, placing in the window of his shop at 124 Piccadilly a barrel-shaped padlock version of his patent lock, made specially by Maudslay and bearing the legend: The Artist who can make an Instrument that will pick or Open this Lock, shall Receive 200 Guineas The Moment it is produced.

As it happened, such an artist was now in their midst. Working to promote Newell’s Parautoptic lock (so called because its design, which featured a kind of shutter around the keyhole, preventing inspection of the lock’s interior by any would-be picker), Hobbs decided on a dramatic gesture, first boldly announcing one day to a group of scientific men gathered at the Crystal Palace that even the very finest British locks were eminently pickable—to prove his point, he produced one of Chubb’s famous Detector locks and, in only a few minutes, picked it on the spot. As the story of Hobbs’s conquest of the Chubb lock circulated, doubts were voiced by critics who were not present at the demonstration. Undeterred, the American issued a formal invitation to Messrs. Chubb, writing a letter on 21 July to inform the great lockmakers that he was to again pick one of their locks, this time in the presence of several important and impartial judges, including a former Secretary to the Board of Trade. A letter, issued the following day and signed by the eminences, made the results a matter of public record:

We the undersigned hereby certify that we attended, with the permission of Mr. Bell, of No. 34 Great George-street, Westminster, an invitation sent to us by A. C. Hobbs, of the City of New York, to witness an attempt to open a lock throwing three bolts and having six tumblers, affixed to the iron door of a strong-room or vault, built for the depository of valuable papers, and formerly occupied by the agents of the South-Eastern Railway; that we severally witnessed the operation, which Mr. Hobbs commenced at 35 minutes past 11 o’clock A.M., and opened the lock within 25 minutes. Mr. Hobbs having been requested to lock it again with his instruments, accomplished it in the short space of 7 minutes, without the slightest injury to the lock or door. We minutely examined the lock and door (having previously had the assurance of Mr. Bell that the keys had never been accessible to Mr. Hobbs, he having had permission to examine the keyhole only). We found a plate on the back of the door with the following inscription: “Chubb’s New Patent (No. 261,461), St. Paul’s Churchyard, London, Maker to Her Majesty.”

Hobbs had used a series of specially designed tools and small weights to undo what Chubb’s advertisements called the “perfect security” of his lock in less than a half-hour, and the ease of his feat sent shockwaves through the British locksmithing community. No one from Chubb’s firm had accepted Hobbs’s invitation to attend the demonstration, but the British lockmaker eventually accepted Hobbs’s success, announcing that his locks would in future be updated and improved to prevent the methods Hobbs employed. And even as Hobbs was picking Chubb’s lock, he had already set his next and greatest test, the defeat of Bramah’s famous challenge lock, in motion. A committee of learned men was organized to supervise the arrangements and the lock was removed from its half-century-long perch in the Piccadilly window and taken to an upstairs room at Bramah’s shop (which was now operated by his sons as Bramah & Co., Joseph having died in 1814), where it was sealed within a kind of wooden box so that only the keyhole was accessible. The room was given over to Hobbs’s exclusive use and the American was allowed thirty days to complete his task. Work began on 24 July and, after being suspended for several weeks during a procedural disagreement, resumed on 16 August. On 23 August, Hobbs called in the committee to announce he had broken the challenge lock, and in several demonstrations over the next few days, repeatedly picked and restored Maudslay and Bramah’s device in the presence of witnesses. In all, it took him fifty-one hours, spread over sixteen days, to accomplish his goal.[1]

After a great deal of disputation about the condition of the lock, the American’s methods, and the precise terms of the challenge—much of it played out in the pages of daily newspapers like the Observer, which published both panicked letters from a banking community who had seen the vulnerabilities of their security publicly exposed and the rationalizations of the lockmakers trying to defend their now suspect products—a panel of arbitrators appointed to settle the affair finally ruled in favor of Hobbs. And so in early September, Bramah & Co. grudgingly paid the American £210 (the equivalent of two hundred guineas). Yet the lock controversy had not yet quite played itself out. The week after Hobbs was paid, a certain Mr. Garbutt—a respected locksmith who had been responsible for the locks at the Crystal Palace cashier stations—announced that he would attempt to defeat the Newell Parautoptic lock, which like the Bramah had also been made available for public challenge at Crystal Palace.

The Newell lock was removed to a private home at No. 20 Knightsbridge, where it was secured within a wooden box like the one that had enclosed the Bramah lock the month before. At the end of the thirty days Garbutt had been allotted, he returned the lock, having failed to open it. (Trying to pick the Newell lock had by this point become something of a sport, as British engineers sought to restore some sense of national pride. Indeed, in early 1852, following a presentation of a paper by Hobbs at the Royal Society of Arts, it was claimed by an audience member that the Parautoptic lock had in fact been picked by a London locksmith. The newspapers began circulating the rumor until Hobbs went public with the full story, eventually acknowledged by the locksmith who had supposedly defeated the Newell device, that he had in fact simply taken an impression of the key and copied it. This copy, wrote Hobbs in the Observer with not a little bit of sarcasm, was, not surprisingly, “found to lock and unlock the lock as readily as the original key.”)

• • •

By the spring of 1852, the lock controversy had finally begun to ebb. In due course, the Jury Reports of the Great Exhibition were issued. Functioning in effect as the final scorecards for the “honourable rivalry” that had played out in the various departments of the Exhibition, these reports were prepared by prominent judges; Berlioz, for example, wrote the assessment of the musical instrument competition. Much to everyone’s surprise, the jury on locks declared itself “not prepared to offer an opinion … on the comparative security afforded by the various locks” that had come before it. Of this opinion, a leading magazine of the day observed, “The jury seems to have consisted of the only persons in England who did not hear of the famous ‘lock controversy’ of last year; for one can hardly imagine that, if they had heard of a matter of so much consequence to the subject they were appointed to investigate, they would have altogether abstained from saying anything about it.”

Yet by then all the rhetoric was of increasingly little consequence. The Bramah and Chubb companies continued to thrive in their businesses with newly improved technologies inspired by Hobbs’s handiwork. Both firms are today still mainstays of the British security industry—Chubb is a multinational manufacturer of safes and surveillance devices, and Bramah, which still maintains a shop in central London, is primarily a maker of specialty locks for use in high-end furniture and residential design applications. Meanwhile, Hobbs took his prize money and instead of returning to New York and his bosses at Day & Newell, decided to stay in London, patenting his own lock, based on the design of the Parautoptic, and opening Hobbs & Co. at Cheapside in the heart of the City of London’s banking district.

Hobbs remained in London for nearly a decade before returning to the US in 1860, where he worked as an engineer and designer for the Howe Sewing Machine Company and later at the Remington Arms Company. There is no record of Hobbs’s involvement in lockmaking after his return. In any event, new talents had by then begun to emerge in the field, including Linus Yale, who as a young locksmith in upstate New York—far from the bright lights of the Great Exhibition—had picked the Day & Newell lock, it was said, using only a wooden stick. Hobbs’s firm, which he sold but which retained his celebrated name, continued to operate for over ninety years at its original location in the City of London, and in 1954 was itself acquired—by the Chubb Group.

- While the challenge lock itself had reportedly never been broken, Hobbs acknowledges in his accounts of the “lock controversy” that his was not in fact the first time someone had picked a Bramah lock. In 1817, an employee of the Bramah firm by the name of Russell apparently devised a means of picking his boss’s locks and even took out advertisements touting his services to owners of Bramah locks who had lost their keys. See A. C. Hobbs, Construction of Locks and Safes, ed. Charles Tomlinson (Bath, UK: Kingsmead Reprints, 1970).

Jeffrey Kastner is a New York-based writer and senior editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.