A Brief History of String

From the eruv to the quipu

Sabrina Gschwandtner

A tactile line with innumerable uses, string is a modest material that has also been tied, hung, and otherwise handled in order to express abstract thought. String has delineated religious space, described narratives, denoted mathematical data, and possibly even delivered language.

A timeline of three principal ways in which string has been used to embody ideas also reveals a history of contested or suppressed information. A brief history of string is thus a record of attempts to break or recover links between meaning and its material.

The Torah prohibits certain kinds of work in public domains during the Sabbath, but allows that work to be done in an enclosed private area.

The Hebrew word eruv means “to mix” or “join together”; an eruv serves to integrate a number of private and public properties into one larger private domain. Within the space delineated by an eruv, certain work, like carrying an umbrella or pushing a stroller, becomes permissible.

There are currently over 150 eruvim in communities throughout the world. The Washington DC eruv includes the White House. The Strasbourg eruv encompasses the European Court of Human Rights.

There are numerous regulations concerning the placement of an eruv. Those who use one have an obligation to ascertain, each week, whether the eruv is functional. A weekly inspector traverses the line of the eruv to ensure it is intact. And a hotline or website reports on its status. I called several eruv hotlines:

Today is April seventh. For this Shabbos, the eruv is up and operation.

—Chicago, Illinois

Friday afternoon, July the fourteenth, the eruv is kosher.

—Baltimore, Maryland

May fifth: Shabbat is at 7:35. The Skokie eruv is kosher.

—Skokie, Illinois

I met with two rabbis in Brooklyn Heights, New York, near where I live. The eruv in my neighborhood is a series of strings tied from telephone poles running parallel to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, through Cadman Plaza, up Jay Street, across Livingston Street, then along Hoyt Street until it hangs down from a tree branch on Second Street. An eruv is supposed to form a closed loop, but the rabbis told me that their eruv is being combined with its neighboring Park Slope eruv, which is probably why the Hoyt Street line is broken. The Brooklyn Heights rabbis referred me to an eruv inspector in Park Slope. We spoke several times by phone, but he ultimately declined to take me on his weekly eruv walks, saying that he preferred not to publicize the eruv because of a history of controversy.

Eruvim have provoked numerous acrimonious conflicts over definitions of public property and religious space. In 2002, for example, a New Jersey town claimed that the eruv constituted an improper government endorsement of religion. A local court sided with the borough, which ordered the eruv be removed. That decision was later overturned on an appeal; the new decision was upheld in subsequent court rulings. In 2003, the Supreme Court refused to hear the New Jersey municipality’s appeal, keeping the eruv legal.

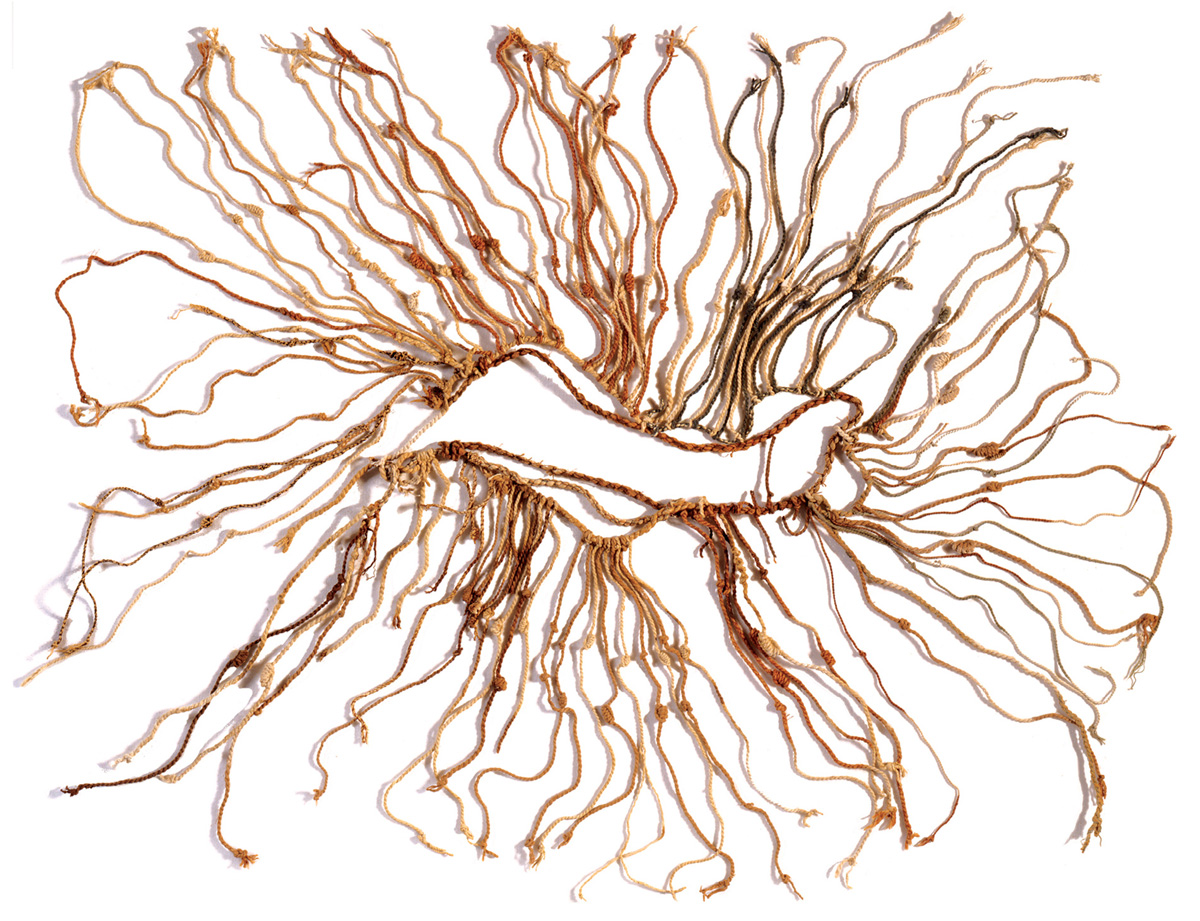

Quipus were presumably read by touch and sight. Knots were continuously tied and retied, an unfixed means of inscribing.

Only about 600 pre-Columbian quipus survived the Spanish conquest and are preserved in private and museum collections. The Spanish destroyed quipus in order to establish the new law of writing. The ancient knowledge that the Andean people kept within their quipus is long lost.

While quipus are generally believed to contain genealogical, bureaucratic, economic, and astronomical information, some researchers are working to translate them into language. Professor Gary Urton, a leading anthropologist in this field who has compiled an extensive quipu database, claims that quipus can be read as a kind of three-dimensional binary code. This would be similar to the way computers translate eight-bit ASCII into letters and words.

Last August, Dr. Urton and his associate Carrie Brezine (a mathematician, spinner, and weaver) reported that they may have decoded the first word: Puruchuco, a place name.

Quipus also provided a visual form for the concept of place. As Cecilia Vicuña, a Chilean poet and artist based in New York who has been making artwork based on the concept of quipu for over forty years, told me, “In Andean thought … they conceptualized themselves—the totality of their humanness—as one huge quipu. And the core of that quipu would be [the Incan capital] Cusco. From this city, virtual straight lines would set out in all directions, just like a quipu. And the knots would be sacred sites … place[s] where transformation and passing from one dimension to the next occurs.”

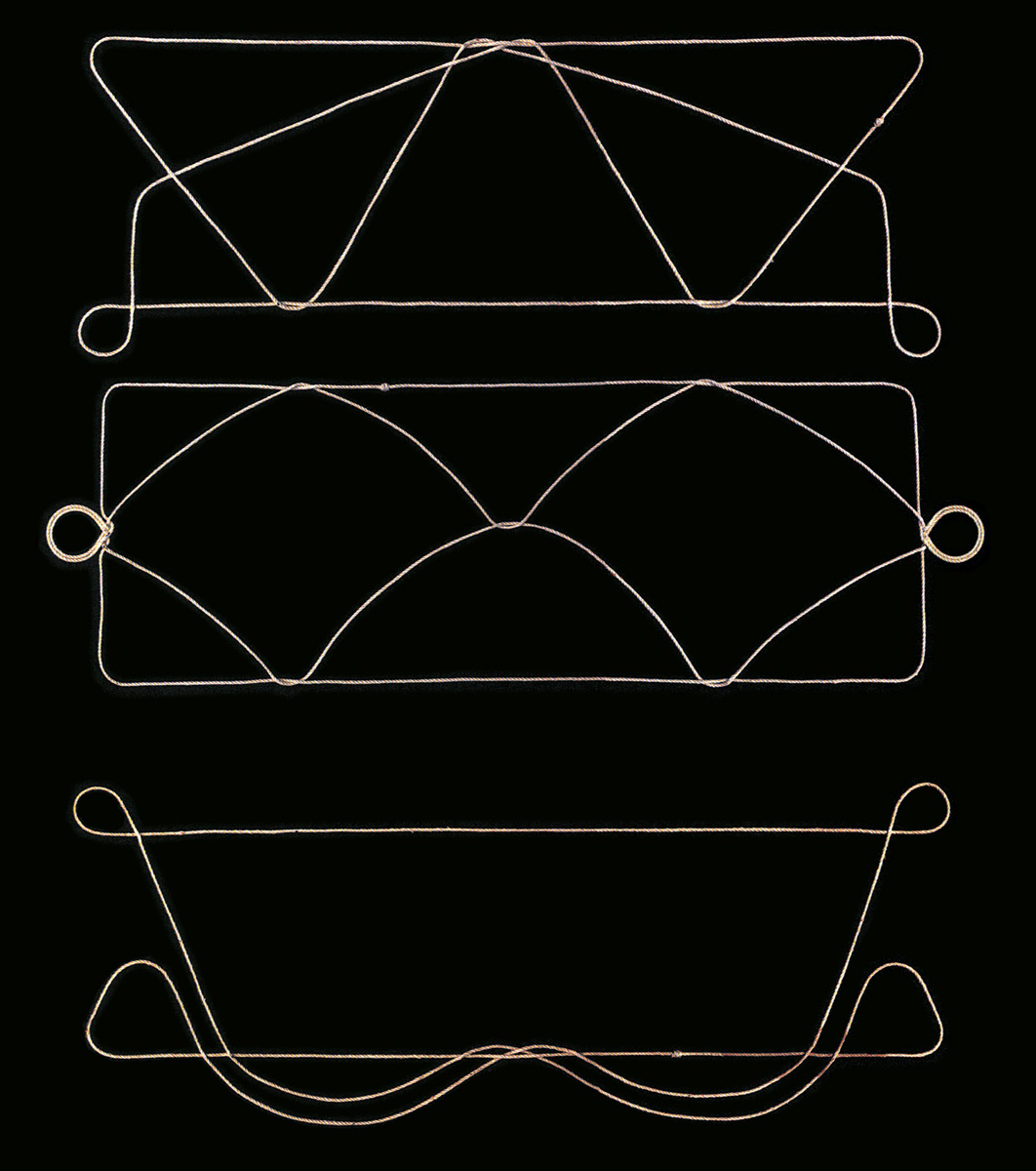

Though string figures have probably been made for thousands of years, the history of collecting them is only about a hundred years old. Alfred C. Haddon, a zoologist, is credited as the first person to devise a scientific language for recording how a string figure is made. Anthropologists avidly collected string figures in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The first two decades of the 1900s were known as “The Golden Age of String Figures” because so many were notated during that period.

Perhaps because missionaries who viewed string figures as a pagan holdover exerted pressure on practitioners to stop making them, the meaning of the various forms is still largely elusive. Evidence exists that some early collectors suspected that string figures might possess a significance that escaped them. As anthropologist Franz Boas wrote in 1888:

It would seem that as yet there is no substantial evidence that the construction of string figures is other than a recreation. I say “as yet” for new discoveries may at any time alter our views on this question.

Anthropologists still classify string figures as a pastime: something that prevents boredom. Mark Sherman, director of the International String Figure Association, spoke about the kinesthetic feeling of producing a string design as he showed me several ornate figures. “String figures, once completed, are dissolved within seconds. The wonderful thing about string figures is the process of making them … the feel of the string on your fingers. The kinesthetic sense of making string figures is the same gratification you get from flying a kite; you can feel the tugging of the string— the motion is what’s pleasurable. There is a sense of tension, and then when you drop loops off your fingers and display the design, you have a sense of release. It’s a very dynamic process.”

Yet it is known that in some areas of the world, string figure practice was more than just play and was connected to religion, mythology, and divination. The Navajo honored string figures as a gift from Grandmother Spider, and only made them during the winter when spiders were inactive. Among the Kwakiutl of British Columbia, certain string figures were passwords that gave entry into secret societies. The natives of the Gilbert Islands believed in a guide to the underworld who required the deceased to perform with him certain series of string figures. In some locations, string figures also acted as good luck charms to help ensure a successful harvest or hunt.

Harry Smith (1923–1991), the painter, filmmaker, and musicologist who made significant contributions to anthropology and to the preservation of America’s cultural heritage, considered himself the world’s leading authority on string figures. When he died, Smith left behind a thousand-page manuscript, a collection of string figure patterns mounted on black board, and a box of index cards related to his research. On each card, Smith notated the method for making the string figure, along with a list of features (such as, “this string figure has three diamonds”). Smith would sort the cards into different piles based on cross-cultural commonality, seeking universal threads.

The author wishes to thank Jeff Place, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings; Vuka Roussakis, American Museum of Natural History; Mark Sherman, ISFA; Rani Singh, Harry Smith Archives; Sally Slate, American Museum of Natural History; and Cecilia Vicuña.

Steve Connor, “Inca May Have Used Knot Computer Code to Bind Empire.” The Independent, 23 June 2003.

Manuel Herz & Eyal Weizman, “Between City and Desert.” AA Files no. 34, Autumn 1997.

Caroline Furness Jayne, String Figures and How To Make Them (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1962). This is an unabridged reproduction of the work first published by Charles Scribner’s Sons in 1906 under the former title, String Figures.

Tina Kelley, “Town Votes for Marker Used by Jews,” The New York Times, 25 January 2006.

Charles G. Moore, “The Implication of String Figures for American Indian Mathematics Education,” The Journal of American Indian Education, vol. 28, no. 8, October 1988.

Mark Sherman, videotaped interview, 25 September 2005.

Bill Sillar, “Communicative Technologies in the Ancient Andes: Decoding the Inka Khipu,” Current Anthropology, vol. 46, no. 4, August–October 2005, pp. 690–691.

Cecilia Vicuña, videotaped interview, 22 September 2005.

Nicholas Wade, “Those Ancient Incan Knots? Tax Accounting, Researchers Suggest,” The New York Times, 16 August 2005.

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eruv

www.darsie.net/string/ [link defunct—Eds.]

Sabrina Gschwandtner is a New York–based artist who works with film, video and textiles. She received her B.A. in art and semiotics from Brown University and is currently writing a book on knitting. She will exhibit a knit and text installation at the Museum of Arts & Design, New York, in January 2007.