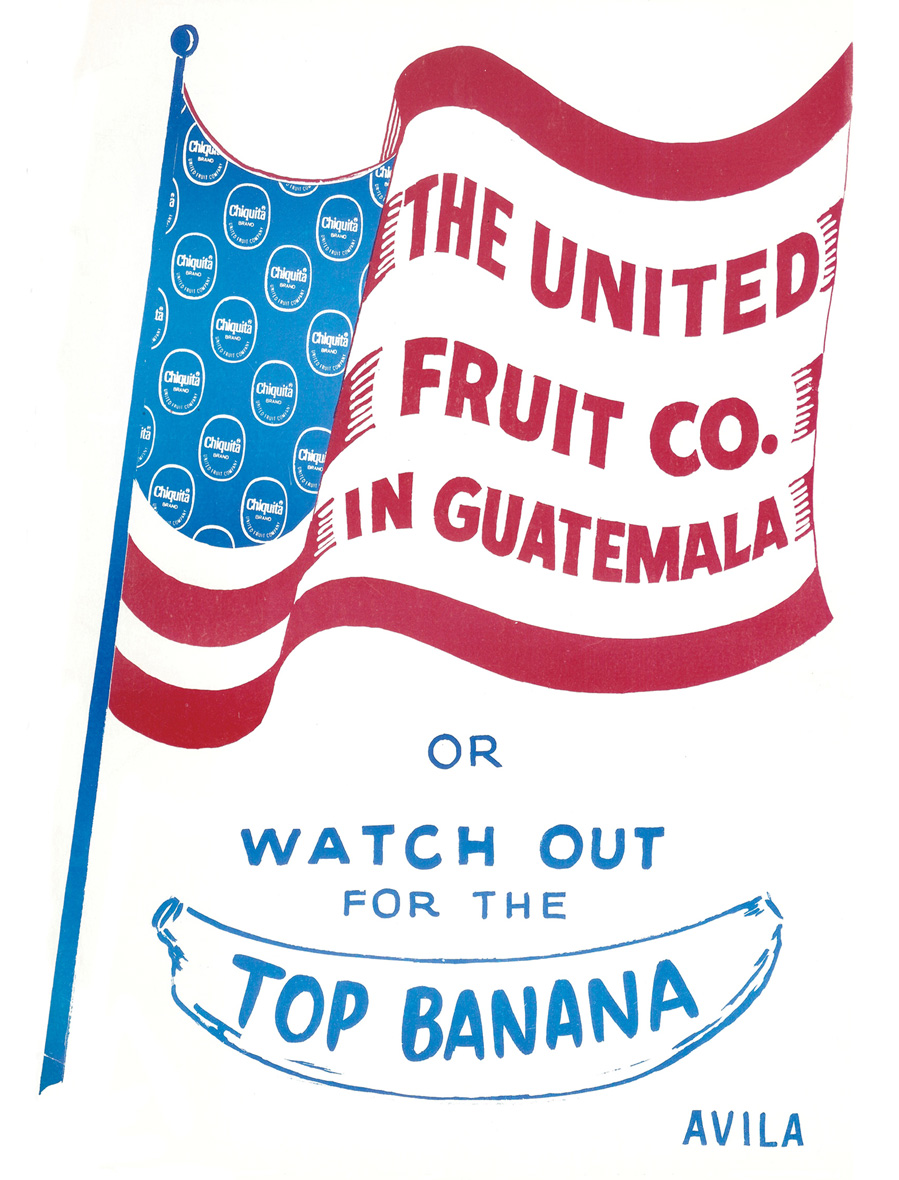

Watch Out for the Top Banana

Edward Bernays and the colonial adventures of the United Fruit Company

Larry Tye

It was a war in which few shots would be fired, but upon which the very safety of the Free World was said to hang. It was a war where words and symbols were the primary weapons and Sigmund Freud’s nephew, Edward L. Bernays, supplied the ammunition. And in 1954 Bernays’s arsenal was as well-stocked as it would ever be.

He had a plan for spying, one that involved putting in place a network of moles. He had a plan for waging psychological warfare, and another plan for wooing the press. He even had a plan for contrasting his Godless enemy’s outlook on twenty-two vital issues with those of Christianity. All this for an undeclared war waged on behalf of United Fruit, one of America’s richest companies. A war fought in quiet alliance with the US government, on foreign soil, against the elected government of Guatemala. A war that, in the mid-1950s when the Cold War seemed ready to boil over, was seen by those waging it as a crusade to keep Moscow from gaining a beachhead a thousand miles south of New Orleans.

Bernays helped mastermind that war for his fruit company client, drawing on every public relations tactic and strategy he had refined since giving birth to the profession forty years before. Historians have written extensively about that propaganda campaign, but always relied on the sketchy account Bernays provided in his autobiography and the limited materials available from the American and Guatemalan governments. Upon Bernays’s death in 1995, however, Library of Congress made public fifty-three boxes of his papers on United Fruit that paint in vivid detail his behind-the-scenes maneuvering and show how, in 1954, he helped topple Guatemala’s left-leaning regime. Those papers offer insights into how the United States viewed its Latin neighbors as ripe for economic exploitation and political manipulation—and how the propaganda war Bernays waged in Guatemala set the pattern for future US-led campaigns in Cuba and, much later, Vietnam.

“This whole matter of effective counter-Communist propaganda is not one of improvising,” Bernays noted in a 1952 memo to United Fruit’s publicity chief. “What is needed,” he added, is “the same type of scientific approach that is applied, let us say, to a problem of fighting a certain plant disease.”

• • •

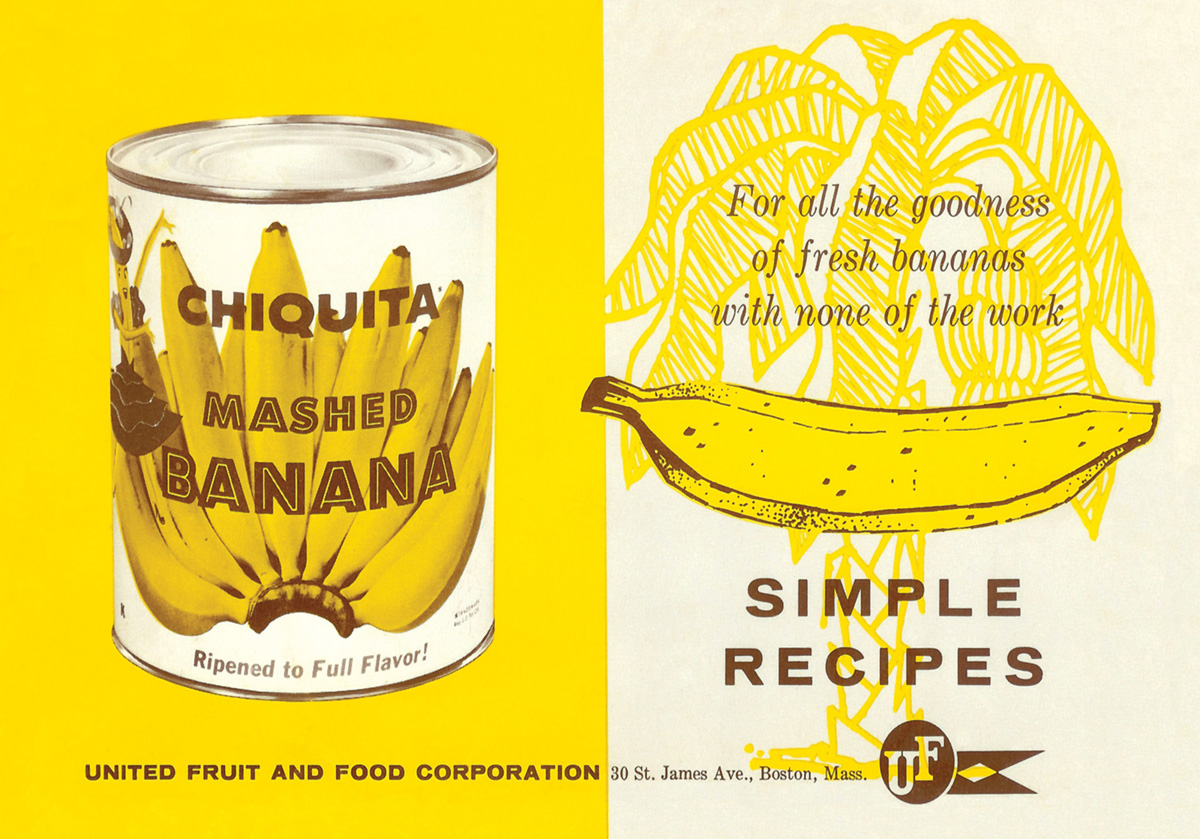

The United Fruit Company was born over a bottle of rum. In 1870, Lorenzo Dow Baker, skipper of the Boston schooner Telegraph, pulled into Jamaica for a taste of the island’s famous distilled alcohol and a load of bamboo. While he was drinking, a local tradesman came by offering green bananas; Baker bought 160 bunches at twenty-five cents each. He resold them in New York for up to $3.25 a bunch, a deal so sweet he couldn’t resist doing it again. By 1885, eleven ships were flying under the banner of the new Boston Fruit Company, bringing to the United States ten million bunches of bananas a year. United Fruit was formed in 1899, with assets that included more than 210,000 acres of land across the Caribbean and Central America and enough political clout that Honduras, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region became known as “banana republics.”

The company also soon had a kingpin worthy of its swashbuckling history: Samuel Zemurray, better known as Sam the Banana Man. Big and blunt, the Jewish immigrant from Russia used a blend of cleverness and cunning to buy up a bankrupt steamship company and plot the overthrow of the Honduran government, to acquire millions of dollars of United Fruit stock, and, convinced it was being mismanaged, to insert himself as head of the Boston-based firm. By 1949, Zemurray had built United into one of America’s biggest and best-run companies, with fifty-four million dollars in earnings and control of more than half the US market in imported bananas.

But he always was looking to sell more, especially during the winter, when frosts made shipment and storage more difficult. Which is why, in the early 1940s, he brought on as his public relations counsel Edward Bernays, a diminutive man who had proven his ability to act big by convincing a generation of American women to smoke the cigarettes made by his client American Tobacco Co., luring a generation of children into carving sculptures from Ivory Soap bars made by client Proctor and Gamble, and generally tapping the ideas of his uncle, Sigmund Freud, on why people behave the way they do, only to reshape those behaviors for the benefit of his paying customers.

One way to boost sales for United Fruit, Bernays reasoned, was to link bananas to good health. Bernays also connected the fruit to national defense, a link less obtuse than it seems since United’s “Great White Fleet” was used in both world wars to ferry supplies and troops. On top of that were campaigns to get bananas into hotels, railroad dining cars, airplanes, and steamers; to feed them to professional and college football teams, summer campers, YMCA and YWCA members, Boy and Girl scouts, and students of all ages; to push them with companies making cake, cookies, ice cream, and candy; and to secure a place for them in movie studio cafeterias and at top-of-the-line resorts in places like Palm Beach and Sun Valley.

But Bernays was farsighted enough to realize that if United Fruit wanted to cement its position in the North American economy, it had to teach North Americans about their neighbors to the south. The mission wasn’t just to sell bananas, he told Zemurray, but to sell an entire region of the hemisphere. So he set up one of his trademark front groups, the Middle America Information Bureau, which churned out brochures and press releases with titles like “How about Tomato Lamburgers?” The Bureau was in part an honest attempt to educate, providing scholars, journalists, and others with the latest information about a nearby place most Americans knew nothing about, but where did the Bureau get its material? From United Fruit, of course. “I wrote articles, one after another, I ground them out and they were sent to newspapers throughout the country,” recalled Samuel Rovner, who went to work for Bernays right after graduating from the Columbia School of Journalism in 1943. “I didn’t know much about Latin America. I did some research now and then but for the most part it was based on material that came from the United Fruit Company.”

• • •

By the mid-1950s, questions of public education, and even of selling bananas, were being subsumed by questions of politics for Bernays and his employers at United Fruit.

Guatemala was the hot spot, and had been since 1944, when a mass uprising ended the fourteen-year rule of strongman General Jorge Ubico. Juan José Arévalo, a professor living in exile in Argentina, returned home and was swept into office with more than 85 percent of the vote. Arévalo introduced a democratic political system and, for the first time, gave workers the right to organize and strike. In March 1951, Arévalo was succeeded by his defense minister, Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. Árbenz picked up the pace of change, enacting a modest income tax, upgrading roads and ports, and, most significantly, pushing a program to redistribute uncultivated lands owned by large plantations. Between 1952 and 1954, the Árbenz government confiscated and turned over to one hundred thousand poor families 1.5 million acres—including, in March 1953, 210,000 acres belonging to the United Fruit Company.

United Fruit had chosen Guatemala half a century before in large part because of its pliable government. Guatemalan rulers exempted the company from internal taxation, helped it maintain control of the country’s only Atlantic seaport and virtually every mile of railroad, and guaranteed workers would get no more than fifty cents a day. It was a capitalist’s dream. By the time Arévalo took over, United Fruit was Guatemala’s number one landowner, employer, and exporter. The Arévalo reign raised a red flag for the company. Workers went on strike at its banana plantation and seaport, forcing it to make concessions in a labor contract, and United Fruit was targeted as Guatemala’s most glaring symbol of hated Yankee imperialism. Árbenz went several steps further, vowing to build a highway to the Atlantic to break United Fruit’s stranglehold on inland transport, a second port to compete with United Fruit’s facilities at Puerto Barrios, and a hydroelectric plant to end the near-monopoly of US-backed power suppliers. He also wanted to take another 177,000 acres of United Fruit Company land. The company would be reimbursed about three dollars an acre. That was what United Fruit said in its tax statements the fallow land was worth, but it was far less than the seventy-five dollars an acre the company claimed once the land was expropriated.

All of this reinforced alarms Bernays had been sounding since he visited the region early in the Arévalo regime. He warned that Guatemala was ripe for revolution, and that the communists were gaining increasing influence. And he counseled the company to scream so loud the United States would step in to check this threat so near its border. The way to do that, he argued, was via the media. He had picked out ten widely circulated magazines, including Reader’s Digest and the Saturday Evening Post, and said each could be convinced to run a slightly different story on the brewing Guatemalan crisis. “In certain cases, stories would be written by staff men,” Bernays wrote. “In certain other cases, the magazine might ask us to supply the story, and we, in turn, would engage a most suitable writer to handle the matter.” While United Fruit didn’t move as quickly as he wanted, articles began appearing in the New York Times, New York Herald Tribune, and other publications, all discussing the growing influence of Guatemala’s communists. That liberal journals like the Nation also were coming around was especially satisfying to Bernays, who believed winning over liberals was essential to winning over America.

Reporters weren’t the only ones willing to see the tropics through Bernays’s lens. In January 1952, he took on a two-week tour of the region the publishers of Newsweek, the Cincinnati Enquirer, the Nashville Banner, and the New Orleans Item, a contributing editor from Time, the foreign editor of Scripps-Howard, and high-ranking officials from the United Press, the San Francisco Chronicle, the Miami Herald, and the Christian Science Monitor. Bernays insisted in his autobiography that the journalists were free “to go where they wanted, talk to whomever they wanted, and report their findings freely.” But Thomas McCann, who in the 1950s was a young public relations official with United Fruit, wrote in his memoir that “what the press would hear and see was carefully staged and regulated by the host. The plan represented a serious attempt to compromise objectivity. Moreover, it was a compromise implicit in the invitation—only underscored by Bernays’s and the Company’s repeated claims to the contrary.”

• • •

Bernays was gaining ground with the press but, like a relentless general, each step forward only made him more determined to gain more ground.

In March 1952, Guatemala offered United Fruit the labor contract it had long sought. While company officials saw that as a major triumph, Bernays insisted it was a “tactical retreat” by the communists and “does not mean in any sense that their power has been eliminated.” The appropriate response, he added in a letter to United Fruit President Kenneth H. Redmond, would be “to carry forward the strong aggressive tactics of the United Fruit Company in pointing the finger at Communism in Guatemala.”

In letters over the next two years to Edmund Whitman, the fruit company’s publicity chief, Bernays spelled out the “aggressive tactics” he had in mind. One way to strike out at the regime would be to issue the “first book on Communist propaganda” and outline the “scientific method of approach” needed to fight back. Soon after he proposed hiring Leigh White, “an outstanding investigating expert” working in Egypt, to undertake a “private intelligence survey” of the political situation in Guatemala. That was the first in a series of references by Bernays to a network of intelligence agents, spies of sorts, he helped set up in Central America to be coordinated by “the company’s ‘state department.’” Bernays’s memos to Whitman and to newspaper executives suggest the network did supply valuable information. In a May 1954 letter to David Sentner of the International News Service, he said weapons were being funneled from the Soviet embassy in Mexico City to “Guatemalan reds,” adding that some of that information came from “a very responsible correspondent of ours in Guatemala City” while the rest was from “an equally responsible gentleman in Honduras.” Only select journalists—on what Bernays called his “confidential list of approximately 100 special writers interested in Latin America”—received such sensitive leaks.

In June 1952, Bernays broached the topic of psychological warfare. History suggested how valuable such activities could be, Bernays argued in another memo, writing that in “studies of the Nazi criminals by psychologists, the studies psychiatrists make of court cases after the criminal has been sentenced would indicate that had previous knowledge been had of the situation, one might have coped much more effectively.” In the case of Árbenz and his colleagues, Bernays wanted “information about the cultural background of the individual, his family background, his early upbringing, his education, development of career and a look at the various incidents and activities in his life that might shed light on his personality.”

Events on the ground in Guatemala, meanwhile, were firing up. The Eisenhower administration, which assumed office in 1953, stepped up the pressure on Árbenz. The Guatemalan president responded by hardening his stance, and month by month, the situation edged towards confrontation. The final showdown began on 18 June 1954 when Lieutenant Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas, an army officer living in exile, crossed the border from Honduras with two hundred men recruited and trained by the CIA—a band Bernays called the “army of liberation.” Castillo Armas’s “invasion,” supported by a CIA air attack, quickly achieved its end, and on 27 June a military junta took control of Guatemala. Castillo Armas was named president a week later.

How much of a role did Bernays play in undermining the Árbenz government? His Library of Congress files show he remained a key source of information for the press right through the takeover. Bernays wasn’t the only one pressing United Fruit’s case, of course. The company had powerful friends in the Eisenhower administration, including Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs John M. Cabot, whose brother Tom briefly was United’s president. It also hired Washington lobbyist Thomas G. “Tommy the Cork” Corcoran, one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s brain trusters, and two other public relations experts, John Clements, a powerful conservative, and Spruille Braden, Truman’s Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs. And United Fruit wasn’t the only one pressing for intervention. McCarthyism was at its peak, the Cold War was heating up, and conservatives in Congress and the Eisenhower administration were anxious to take on an apparent Red push in their own hemisphere. Many liberals, afraid of being labeled appeasers, remained silent or joined in sounding the alarm.

But most analysts agree that United Fruit was the most important force in toppling Árbenz, and Bernays was the company’s most effective propagandist. “By early 1954, Bernays’s carefully planned campaign had created an atmosphere of deep suspicion and fear in the United States about the nature and intentions of the Guatemalan government,” Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer write in their 1982 book Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. “In the publicity battle between the Fruit Company and the Árbenz government, Bernays outmaneuvered, outplanned and outspent the Guatemalans.” McCann, the young United PR man, had an even better view of what Bernays was doing: “My estimate is we were spending in excess of $100,000 a year for Edward L. Bernays, just for his consulting services, which was an enormous amount of money in 1952.”

“Everybody in the company hated [Bernays], didn’t trust him, didn’t like his politics, didn’t like his fees,” McCann recalled, “But my sense is we were getting our money’s worth, very definitely. I joined the company in ‘52, just about the time Árbenz made his big move to expropriate our land, and I saw a complete turnaround in the reportage as a result of what Eddie did. … There is absolutely no question that Bernays played a significant role in changing public opinion on Guatemala. He did it through manipulation of the press. He was very, very good at that until the day he died.”

• • •

It is not often that historical figures get a chance to revisit controversies that have plagued them the way Guatemala did Bernays. But he did, in 1961. The setting this time was South Vietnam and, at first, his history seemed to be repeating itself.

He was advising a New York advertising agency that was working for the government of South Vietnam just as America was ratcheting up its involvement there. His advice included precisely the sort of propaganda he’d engineered on behalf of Guatemala, complete with a South Vietnam Information Center and endless fact sheets to “give the readers a picture of the country—geographic, economic, educational, ideological.” Bernays’s special expertise here, as in all his foreign assignments, was handling the press. He had plans for extracting favorable coverage from the Saturday Evening Post, Foreign Affairs, the Atlantic Monthly, and Life. He also knew what to do with TV. On 19 July 1961, he wrote to David Brinkley, then with NBC, saying, “The thought has occurred to us that in connection with your forthcoming program you might care to visit South Vietnam, the Republic in Southeast Asia now fighting back Communist infiltration. If you are interested I feel sure the government of South Vietnam would open its facilities and do everything it could to expedite your visit.”

It is unclear just how long he continued providing such advice, but by 1970—the height of the antiwar movement—he had switched sides, actually proposing to write a paperback book “aimed at men and women interested in having a manual on the how-to of organizing public support for political action at every level to stop the war in Indochina.” Why the switch? The country was turning around on Vietnam, and Bernays, a master at reading public attitudes, appreciated sooner than most establishment figures how deep-seated that antiwar sentiment was. So, even as he continued to defend what he had done in Guatemala, he was offering to put all his insider’s know-how to work to stop this latest crusade against communism. No matter that he was seventy-eight, and that few in the antiwar movement knew or cared about all he had seen, done, and learned in Guatemala. What he was offering them, he told publishers who never took him up on his offer, was a “practical guide to political and public action by a man who for half a century has practiced in this area of public opinion and public relations.”

Larry Tye was a longtime journalist for the Boston Globe and a former Nieman Fellow at Harvard University. He is the author of The Father of Spin: Edward L. Bernays and The Birth of Public Relations (Crown, 1998) and Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class (Henry Holt, 2004). He is currently working on a book about electro-convulsive therapy to be published next fall by Avery/Penguin.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.