Sleight of Light

Magic in the shadows

Jonathan Allen

There is money in shadows.

—Bernard Miller, The Strand Magazine

(July–December 1897)

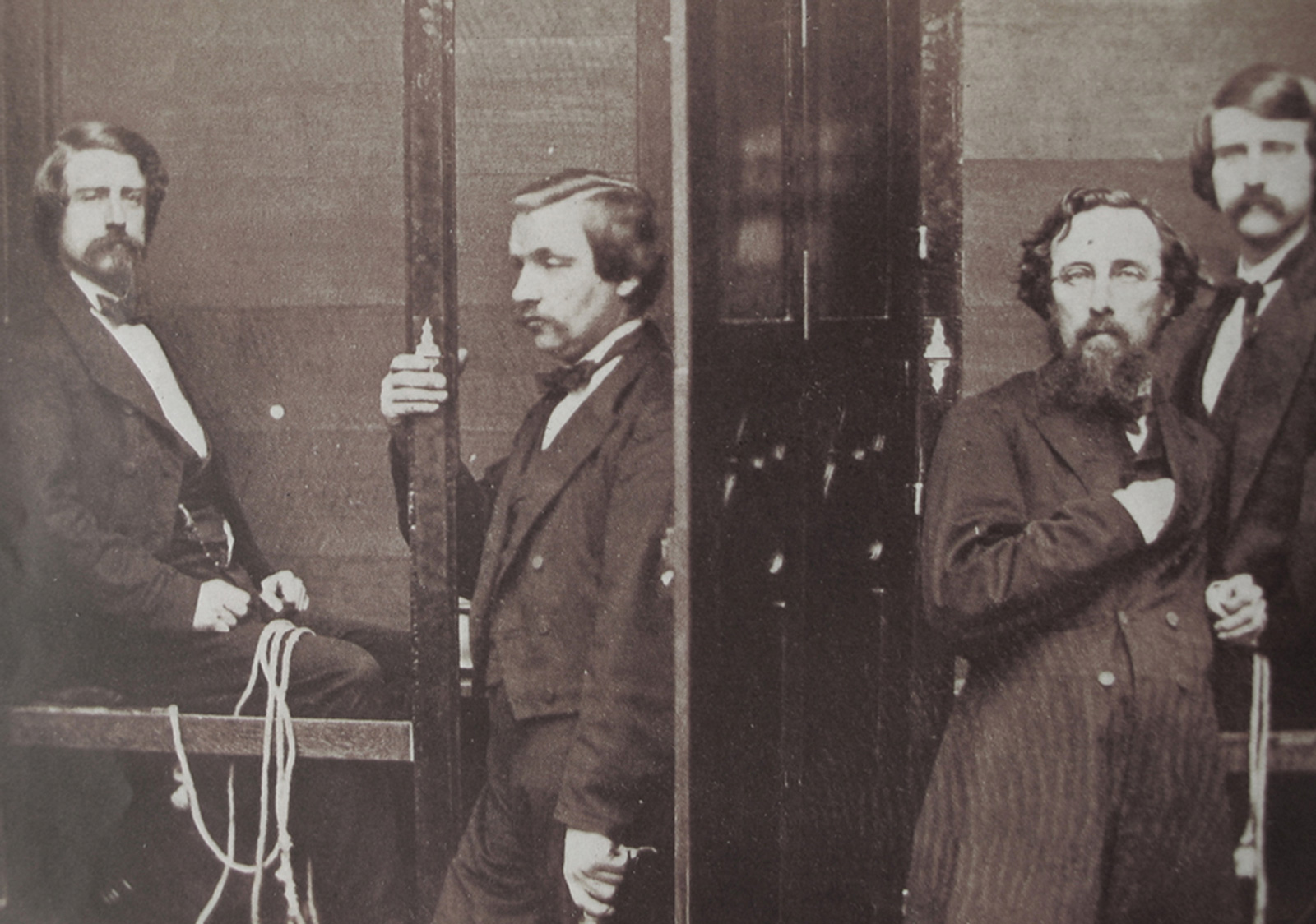

Shortly after midday on 7 March 1865, a narrow annunciating beam of sunlight entered an otherwise darkened room at Cheltenham Town Hall, England. Light was deemed inimical to the spirits that the two charismatic American mediums, the Davenport Brothers, had hoped to summon for the assembled audience from within a raised wooden-paneled séance cabinet. However, when a tiny square of drapery fell from one of the room’s high windows, the unrestrained figure of Ira Davenport was momentarily seen throwing “spirit-animated” musical instruments by hand from the cabinet’s interior. This inadvertent shadow farce was witnessed by amateur magician John Nevil Maskelyne (1839–1917), who within three months had accurately recreated the Davenports’ cabinet using illusion technology alone, wrong-footed the advance of Spiritualism in England, and founded, together with George A. Cooke (1825–1904), one of the greatest dynasties of performance magic’s Golden Era.

The management of shadows on the magic stage is rarely left to chance. Lighting cues for performances tend to follow a dual trajectory, on the one hand creating a fiction of transparency—the magician and assembled props picked out in an array of flattering lighting states—and, on the other, charting a meticulous choreography of concealment where shadows and darkness assist the unseen. Moreover, it is not always within shadows that the mechanics of an illusion are hidden. Shadow misdirection is common, whereby an area of ambiguous illumination is offered intentionally to distract the audience’s suspicious gaze. The resulting focus, or “guilt,” moves away from the body of the magician, who is then free to execute any necessary sleight under the full glare of stage lights. Painted trompe l’oeil shadows also feature on the surfaces, or within the interiors of many magic props, creating effects that confuse volume, orientation, and materiality. In the realm of the audience, it is not by chance that magic shows often feature rapid pyrotechnic sequences. The temporary shadow cast upon a spectator’s retina by a sudden flash of light can provide cover for much necessary stage business.

But shadows enter the history of magic in less covert ways. Shadow-throwers (also known as ombramanists, shadowists, or shadowgraphers) were common by the late nineteenth century in Europe, with celebrated French magician Félicien Trewey (1845–1920) knuckling and fingering over 300 animal and human characters into monochromatic life within a moon-like circle of projected light. Hand-shadowgraphy was widely popularized in England by magicians such as David Devant (1868–1941), and via books where techniques were often presented alongside instructive routines for the would-be drawing-room conjuror. Foot-shadowgraphy became the specialty of another French performer Chassino (Éléonor Chassin, 1869–1955). Colored shadows were first performed by Charles and Maria Drouillat in 1914, but patented in the same year by Max Holden, a possible instance of shadow theft. Shadowgraphy retains its popularity with contemporary practitioners including the Indian duo Amar Sen and Sabyasachi Senby, the former described at www.handshadowgraphy.com as “making love with the creative art of hand shadows since 1973.” In common with their Victorian forebears, the duo’s shadow back-catalogue features contemporary satirical narratives, including a twenty-fingered tribute to the deaths of Princess Diana and Mother Theresa in 1997. Shadow-throwing remains one of magic’s allied arts.

The ubiquitous shadows cast on the white screen by pranksters in today’s movie theaters pay inadvertent homage to cinema’s oedipal relationship to magic, since both Devant and Trewey played important roles in the evolution of the more layered shadowplay of the cinema, which eventually dislodged magic’s hold on popular spectatorship. Trewey was a friend of the Lumière Brothers and arranged the first London presentation of the cinématographe at the Royal Polytechnic Institution in February 1896. Devant, who was by then working closely with Maskelyne and Cooke at the Egyptian Hall in London’s Piccadilly, recognized a rival spectacle and approached Trewey directly. Something of a shadow-war ensued between the two ombramanists, with Trewey refusing all negotiation and Devant eventually securing an alternative device, R. W. Paul’s moving-picture animatographe. A few months later, Devant obtained one of Paul’s devices on behalf of Georges Méliès, owner of the magic Théâtre Robert-Houdin in Paris and eventually Star Films, who had himself been refused terms of use for the cinématographe by Antoine Lumière the previous year. The twin-lensed projection of film’s future—documentary (Lumière) and fantasy (Méliès)—emerged literally from a history of shadows.

Devant’s familiarity with the effectiveness of the theatricalized shadow led to an illusion entitled “The Window of the Haunted House” (1911), essentially a shadow variation on the magic playlet form evolved by the magician during his ten-year association with Maskelyne. An audience committee was invited to the stage to inspect a raised platform upon which rested a large box-like window frame, removed, so Devant said, from a house in which a violent murder had taken place. No other persons were seen to approach or leave the platform, yet a complex shadow murder play was suddenly visible from within the frame featuring a cast of five characters, including a fireman with hoses, and culminating with the room’s interior appearing to be engulfed by flames.

On the surface, this voyeuristic domestic tableau would have appealed to Edwardian tabloid appetites—the Crippen murder had fixated the popular press during 1910 and 1911—yet the unconscious, it could be said, of Devant’s illusion belonged to the proceeding era, one in which Victoria had spent the forty years after Prince Albert’s death passing through various intensities of mourning black, her public body itself a gradually resolving shadow. The period was characterized by what Philippe Ariès termed la mort de toi (“thy death”), an increasing intolerance of separation from those to whom one is closest that, during a period of high mortality, caused mourners to seek consolation in spiritualism and expressions of exaggerated grief.[1] Mortality pervades Devant’s “shadow people” as the illusion was elsewhere known, since they are cast by human beings who are not just out of sight (like the many hidden performers of the popular spectacles d’ombres of the same period), but from figures that, through illusionistic means, seemed never to have existed, or to have existed beyond comprehended realms. These were shadows of shades, a kind of augmented tenebrosity pertinent to the anxieties of an era withdrawing from Christian assurances, and haunted by the new and unfamiliar ghosts of Freud and Darwin. Devant’s audiences were increasingly disturbed by their own shadows, let alone the perplexing live memento mori conjured upon his stage.

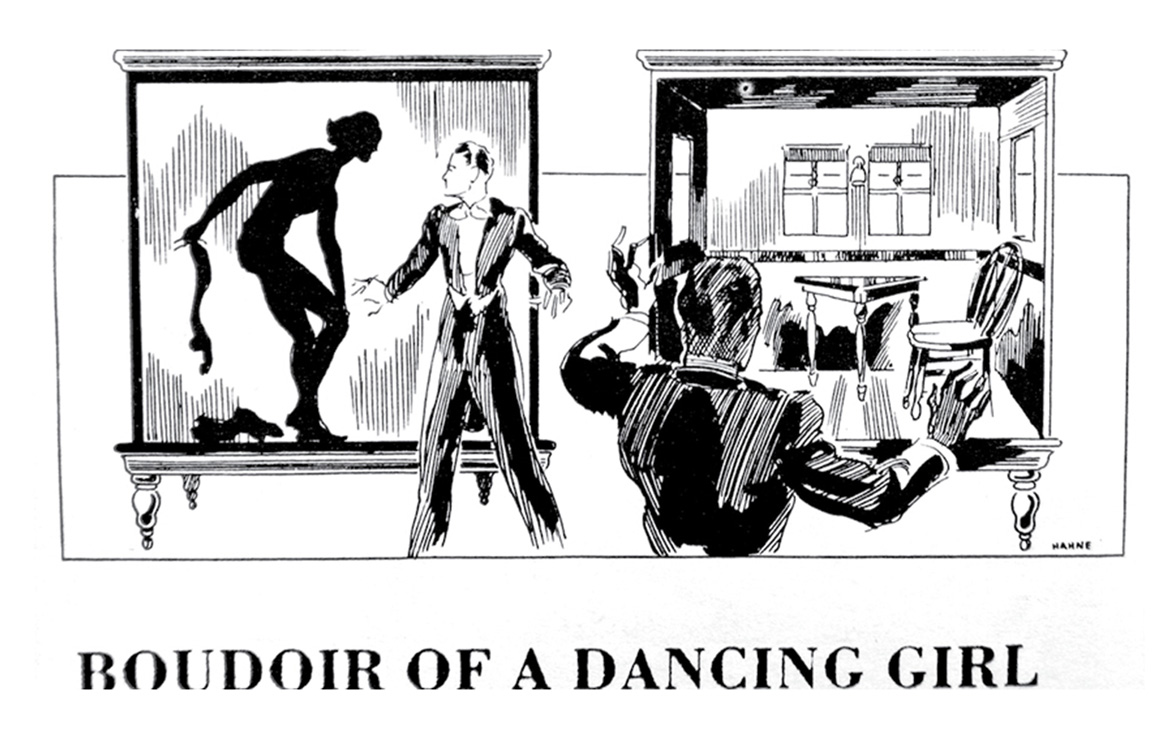

Devant’s illusion was the first in a number of subsequent box-type shadow illusions using differing methods—including “Boudoir of the Dancing Girl” (William Larsen and T. Page Wright, circa 1920); “Shadow Pagoda” (Cyril Yettmah, circa 1930); “The Mark Wilson Spirit Cabinet” (Alan Wakeling and John Gaughan, circa 1980); and “The Origami Folding Shadows” (Jim Steinmeyer, circa 1990)—each contributing to the growing enlistment of female assistant performers who materialized and vanished within magic narratives that reflected the sexual stereotypes of their eras. If the shadow was increasingly gendered within performance magic, then a wand found in the collection of magic historian Mike Caveney offers something of a shadow-phallus. A miniature sibling of the shadow-cane, the object belongs to the community of artifacts known as jouets séditieux, or subversive toys, where selective wood-turning creates cast shadow portrait silhouettes (often politically contentious) when held against a light surface. Caveney’s wand commemorates an important moment of patriarchal transmission when the mantle of the Royal Dynasty of Magic was passed by magician Harry Kellar (1849–1922) to Howard Thurston (1869–1936) on 16 May 1908 at Ford’s Theatre in Baltimore, Maryland. Carved from the wood of the stage on which the event took place, the wand is turned to cast a shadow of the head of each magician at alternate ends, the magicians’ bodies meeting in a crypto-erotic conjoining of potency along the wand’s shaft.

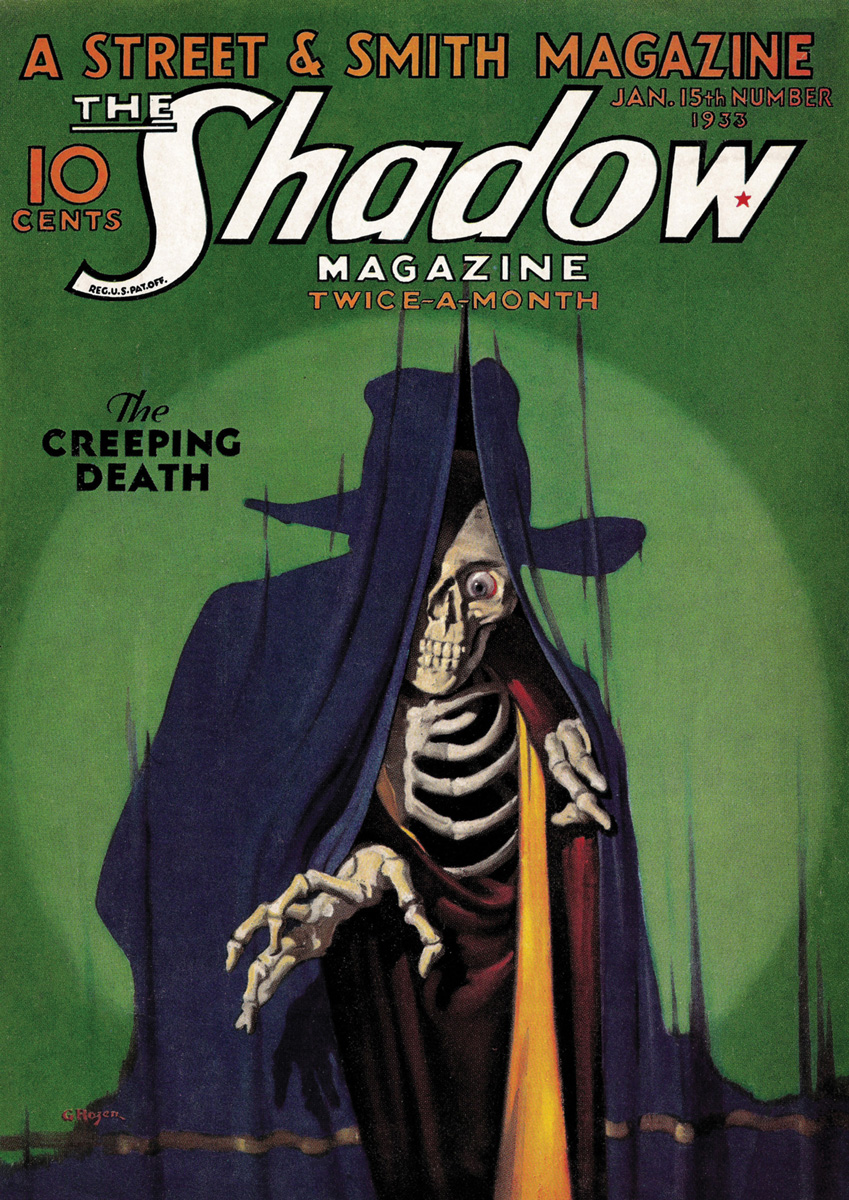

Godfather to all subsequent comic-book superheroes, The Shadow—created by Walter B. Gibson (1897–1985), magician and ghostwriter for many renowned performers including Harry Houdini, Howard Thurston, and Harry Blackstone—made his debut in the early 1930s. Maxwell Grant, Gibson’s pseudonym for many of the early Shadow stories, was an eponymous nod to magic dealers Max Holden (owner of the performance rights to the “Colored Shadows” illusion) and U. F. Grant, who in 1930 had written The Shadow Conjuring Act, a thirteen-page self-published mimeograph laying out alternative patter routines and presentation methods for existing shadow acts. The origins of the superhero are to be found, therefore, not in the distant galaxies or bat-filled caverns of the Hollywood imagination, but in the tenebrous corners of the New York (Holden) and Massachusetts (Grant) magic worlds. “By combining,” Gibson wrote, “Houdini’s penchant for escapes with the hypnotic power of Tibetan mystics, plus the knowledge shared by Thurston and Blackstone in the creation of illusions, such a character would have unlimited scope when confronted by surprise situations, yet all could be brought within the range of credibility.”[2]

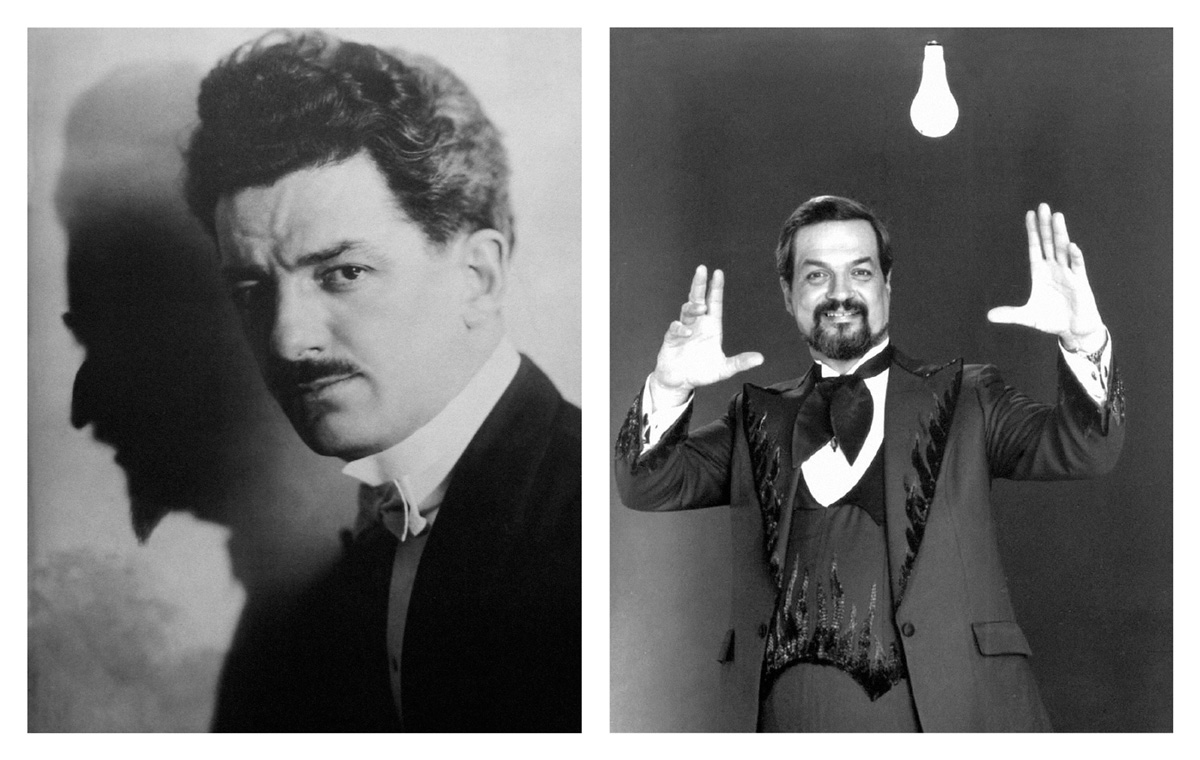

One of the effects U. F. Grant appropriated in The Shadow Conjuring Act was an illusion entitled “Walking Away from a Shadow.” In fact, the effect was created in 1924 by Alexander Stobl, a New York–based Hungarian, for magician Harry Blackstone (1885–1965). The suggestive title brings to mind the German poet and botanist Adelbert von Chamisso’s story of Peter Schlemihl (1813), a young man who sold his shadow to the devil, only to have the devil later try to sell it back in return for his soul. A portrait of Blackstone exists showing the magician casting a demonic shadow against a wall, echoing a long tradition of representations of the mutually lucrative kinship between magic performers and diabolic envoys. Stobl’s innovation involved a freestanding phosphorous-coated screen upon which the magician’s three-quarter length projected shadow could be fugitively retained, allowing him to appear to leave it behind at will. Blackstone’s consequent nightly stage self-portraits point to the receding gothic romanticism of Dorian Gray, and forward to the horrific and unsolicited blast-shadow self-portraits left by victims on the streets of Hiroshima—vivid reminders of science’s oft-bedeviled if not downright errant trajectory. Without any contemporary lighting records available, one might imagine the native green glow of the phosphorous screen prompting Blackstone to balance the stage lighting with a red gel in the footlights, offering the possibility that his stage might indeed have had a somewhat diabolic air, or, with retrospective theatricality, a pulp sci-fi thermonuclear glow.

Harry Blackstone’s interest in stage chiaroscuro continued with “The Floating Light Bulb,” designed and built by Thomas Edison, and considered by many to be his masterwork of illusion. Here, a small light bulb with no discernable source of power illuminated the darkened stage and defied a sequence of physical laws at the fingertips of the charismatic magician. The climax of the trick, developed and popularized more recently by his late son Harry Blackstone, Jr. (1934–97), occurred when the bulb was seen to float, still illuminated, high over the heads of the audience before returning to the magician’s outstretched hand. This example of the penetration of the theater’s “fourth wall” by a magic property remains, according to Blackstone’s widow, Gay, one of only two legally protected “intellectual properties” relating to a performance behavior existing in magic’s long and litigious history.[3]

If the spring sunlight entering Cheltenham Town Hall in 1865 threatened disenchantment, then by the time that Blackstone’s tiny electric light bulb floated out across the vast theaters of Las Vegas and beyond in the 1970s and through into the 1990s, the shadows it cast upon the upturned faces of the audience were secularized, commodified, even gendered. Yet despite this transformation of umbrageous charm, such illusions retain their power to lift spectators momentarily away from their own shadows into collective speculative wonderment, before returning them to the auditorium in firm possession, unlike poor Peter Schlemihl, of their troublesome doubles.

- Philippe Ariès, Western Attitudes Towards Death from the Middle Ages to the Present (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974).

- Walter B. Gibson, preface for Crime Oracle and The Teeth of the Dragon: Two Adventures of the Shadow (New York: Dover, 1975).

- The other belongs to David Copperfield and protects the physical choreography of the performer during his famous “Flying” illusion, the movements of which were meticulously researched from accounts of self-propelled flight during dreaming.

Jonathan Allen is a London–based visual artist, writer, and sometimes stage magician. His performance alter ego, narcissistic gospel magician Tommy Angel, has performed recently at Tate Britain, the De La Warr Pavilion, and in Southeast Asia as part of Allen’s contribution to the first Singapore Biennale. See www.tommyangel.net.