Otto Neurath’s Universal Silhouettes

The father of the Isotype

George Pendle

We are all familiar with them: the accommodating couple found on public lavatory doors, the deer frozen in mid-leap alongside country roads, the car that forever swerves and regains its course, the rocks tumbling unceasingly down the slope of a mountain. Variations on these signs, and thousands of others like them, can be seen across the globe: warning, informing, and sometimes just adorning. Yet despite their universality, the creator of this shadow-world of silhouettes is little known; a sad fate, considering that no other modern philosopher has had such an impact on our day-to-day lives.

Born in Austria in 1882, Otto Neurath would live a more colorful and contrary life than most philosophers, economists, or social scientists, of which he happened to be all three. He studied in fin-de-siècle Berlin, but was so wretchedly poor that he suffered from malnutrition. The experience prompted in him a lifelong disapproval of monetary and credit systems, and, thus chastened, he became an expert in the ancient barter economies of his favorite tribe—the Egyptians.

Returning to Vienna, he embraced Marxism but on his own terms, being sufficiently enamored of the eugenicist Francis Galton’s distinctly uncommunistic treatise—Hereditary Genius—to translate it into German. When not studying economics, he dabbled in literature, writing an extraordinary 500-page preface to the Faust penned by the obscure German Romantic, Ludwig Hermann Wolfram, that doubled the size of an already interminable book and declared Neurath’s Romantic, yet prosaic, tastes. In 1910, he established a school of “war economics” in which he suggested that war would increase the prosperity of a population under attack, an eccentric view that was conclusively rebuffed by the eruption of World War I. In 1918, he became involved with the short-lived Bavarian Republic and was placed in charge of socializing the breakaway country’s entire economy. When the uprising was suppressed, however, Neurath was accused of high treason, although he was eventually pardoned for being politically inscrutable.

The one constant throughout Neurath’s polymathic life was his interest in visual innovation. As a boy, his father had taken him on regular trips to Vienna’s Museum of Art History. Each time he had visited, the young Otto would hurry to the Egyptian exhibition and marvel at the detail and the color of the hieroglyphs on display. In their pictorial course, Otto could see fish being caught, fields being ploughed, slaves being sold, battles being fought, and the spoils of war being carried home in triumph. Here in these wall paintings, ancient Egypt was alive in all its drudgery and glory, clear to the eye and easy to understand.

By comparison, the Greek and Roman antiquities next door displeased the young Otto. The red clay vases and marble bas-reliefs seemed inordinately concerned with the actions of gods, warriors, and mythical heroes, not the day-to-day activities of fishermen, ploughmen, and merchants. They seemed aloof and remote from everyday life and only surrendered factual information about their cultures by chance. Sniffed a disapproving Otto, “Their true role was merely to be beautiful.”

This distinction between informative images and art was to imbue the rest of his life’s work with a humanistic visual austerity. “Orthodox perspective is anti-symbolic and puts the onlooker into a privileged position,” he wrote. “Any picture in perspective fixes the point from which you look. I wanted to be free to look from wherever I chose.” As his views began to harden into shape, he sought freedom from the museum itself, whose pretentious curators with their abstract talk of artistic transcendence he despised. “They were full of their own importance,” he wrote, “and did not understand their public or what it wanted.”

Shunning elitism and searching for a new universality in art, Neurath’s art criticism began to coalesce with his political views. He came to regard “those who drew educational pictures as servants of the public and not as its masters,” for in his view, art for art’s sake was an abomination against utility. He disdained rare and priceless artifacts as fetishes that were obsessed with spectacle instead of the socially informative. Forthwith, he avowed, he would seek a visual expression that was both universal, and useful.

Neurath’s ascetic aesthetic was echoed in his career as a philosopher. In the early 1920s, he was a co-founder of the rigorously empirical Vienna Circle. Neurath and his colleagues—known as the Logical Positivists—declared that metaphysics, religion, and ethics were devoid of cognitive sense, being only expressions of feelings or desires. Only mathematics, logic, and natural sciences, they declared, had any definite meaning. When, during meetings, another member of the Circle made what Neurath considered a scientifically empty claim, Neurath would interrupt by bellowing, “Metaphysics!” With his red beard, bald head, and “combative” attitude—some preferred to call him “rude”—Neurath was a larger-than-life figure.

Yet he was also absolutely sincere in his beliefs. By creating an international picture language as an alternative to written script, Neurath hoped he could satisfy his philosophical, political, and aesthetic views all at once. Not only would it help educate the common Viennese man, but he also believed it might widen the sphere of peaceful cooperation across the world. “The more cooperative man is,” he declared, “the more ‘modern’ he is.”

In this declaration he was not alone, for a curious strand of linguistic utopianism was flooding through Europe at the time. The universal language of Volapük had been created by a Roman Catholic priest in Germany in 1879, following a religious vision he had experienced in his sleep. In 1887, a Polish ophthalmologist had published the first textbook of Esperanto in the hope that it would spread ideas on the peaceful coexistence of different peoples and cultures (“Esperanto” translates as “hopeful”). Ido, a variation on Esperanto, was developed in the early 1900s to be a universal second language to aid in communication between different cultures; Basic English (1930) and Interglossa (1943) were soon to follow. All preached that only communication could prevent war and help mankind progress as one.

This belief in the power of language to both pacify and instigate was not just confined to amateurs. Ford Madox Ford had persuasively argued that World War I had largely arisen as the result of both sides’ misuse, and misunderstanding, of each other’s language, Germany’s militaristic allegory being completely at odds with England’s evasive understatement. Meanwhile, Ezra Pound was working feverishly on his own pictorial language of ideograms, scattering them throughout his Cantos as he attempted to prompt political action through a poetic discourse that was unmediated by the restraints of language. With such great stakes in play, all agreed that miscommunication was to be avoided at any cost. But while Neurath shared the idealistic aims of the constructed languages in his wish to create “a commonwealth of men united in a human brotherhood,” only he was willing to shake free from language’s settled verbal structures and attempt something entirely new. Or rather old. For in fact he wished to create something akin to a hieroglyphic renaissance. “Words separate,” declared Neurath, “pictures unite.”

Following his brush with the firing squad, Neurath had settled into an innocuous job as the secretary-general of the Austrian Association of Cooperative Housing and Garden Allotment Societies. Nevertheless, his zeal for creating a new political and aesthetic language was undiminished. Intent on informing the uneducated Viennese proletariat how the association was improving their living conditions—and perhaps desperate to inject some life into the grim organization—Neurath created giant colored diagrams of the increases in poultry-breeding and vegetable production. Using simple pictures of chickens and carrots, scaled in proportion to the statistics, Neurath discovered a way to popularize statistics, ripping them free from the dusty text of the dour school primer. (That Neurath’s pictograms are intractably associated with today’s school primers shows both our ability to rapidly adopt innovative ideas, and, at the same time, quickly become bored by them). “A silhouette compels us to look at essential details and sharp lines; there are no indefinite backgrounds or superfluities,” Neurath wrote. By using non-realistic symbols as units of representation, visitors to the show could, at a glance, immediately understand complex information regardless of their education. The International System of Typographic Picture Education, or “Isotype,” had been born.

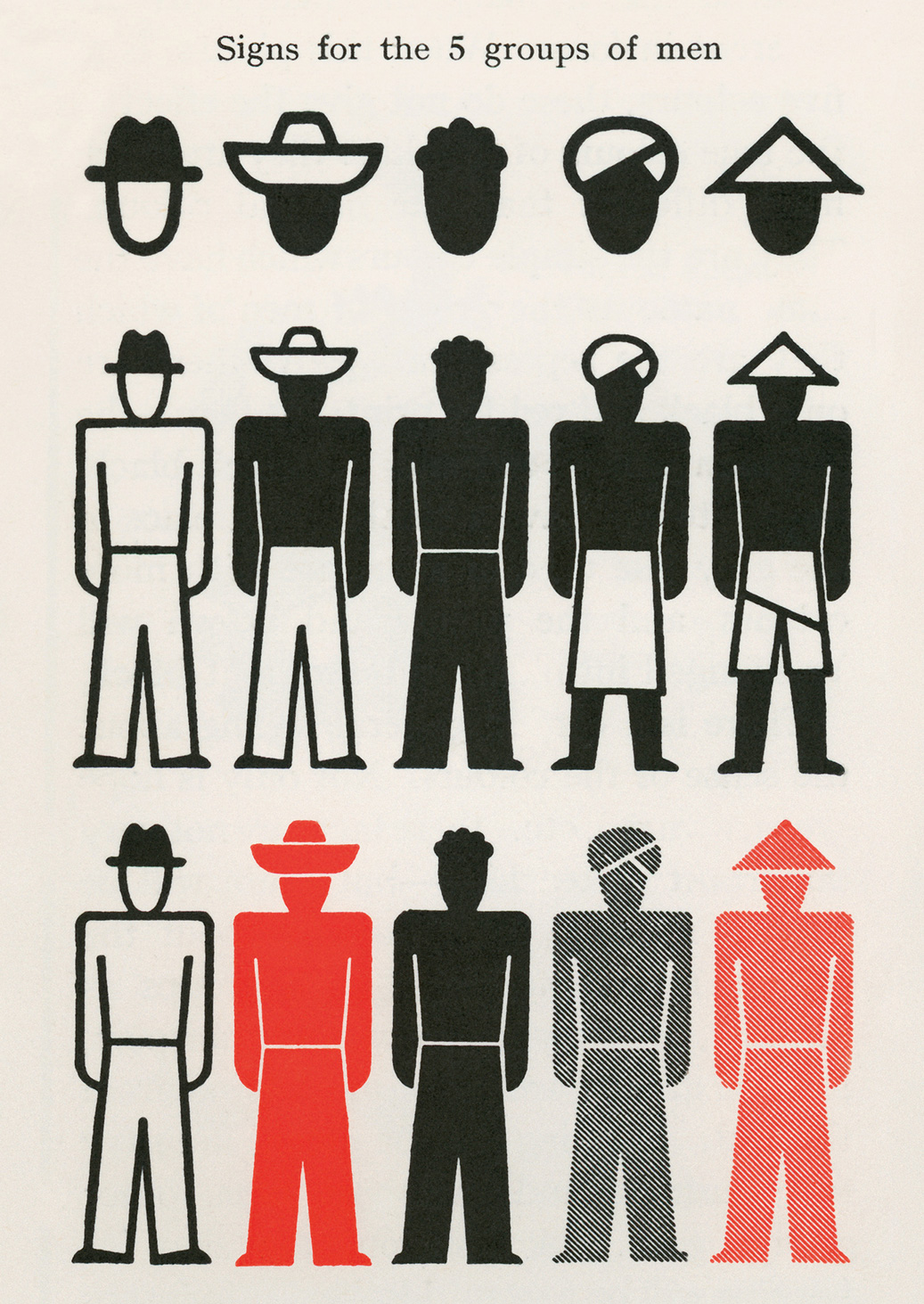

To maintain visual consistency—a crucial factor if the isotype was to be successful—Neurath made print blocks for hundreds of identical symbols. He had soon created a vocabulary of some two thousand isotypes. Units of steel production were depicted by I-beams; strikes were depicted by rows of fists; whenever statistics on workers needed to be shown, the simple silhouette of a man in a flat cap and waistcoat, or a woman in a headscarf and long skirt, was depicted. Neurath had created a Bauhaus of language—functional, formulaic, and, most importantly, for the proletariat.

It was as if a long-forgotten part of the human brain had suddenly been switched on. Within months of Neurath’s first isotype exhibition, the world was awakened to the power of visuals to transfer information. Newspapers across the globe were soon inventing isotypes of their own and beginning to illustrate their pages with them. Like stones buffeted and rounded in the sea, Neurath’s original isotypes were becoming ever simpler, and thus ever more recognizable. Indeed, the isotypes that we see today on lavatory doors are so uncomplicated in their depiction of “male” and “female” that they seem just one step removed from being totally abstract.

Neurath himself would eventually be chased from the continent by a symbol more powerful than any he had created—the Swastika—and would die an exile in England in 1945. Curiously enough, it was only late in his life that he realized the Egyptian hieroglyphs that had excited him as a child and started him on his quest for a universal language had been taken from the inside of an Egyptian tomb. They were not meant to be a language for the living, he mused, but rather one for the dead. Suddenly the afterlife seemed slightly less incomprehensible.

George Pendle has written for the Times, the Financial Times, the Sunday Times, and the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. He is the author of Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons (Harcourt, 2005), and the forthcoming The Remarkable Millard Fillmore: The Unbelievable Life of a Forgotten President (Crown, 2007). He lives in New York.