I Can See Your Ideology Moving

Ventriloquizing Marx

Sally O’Reilly and Ian Saville

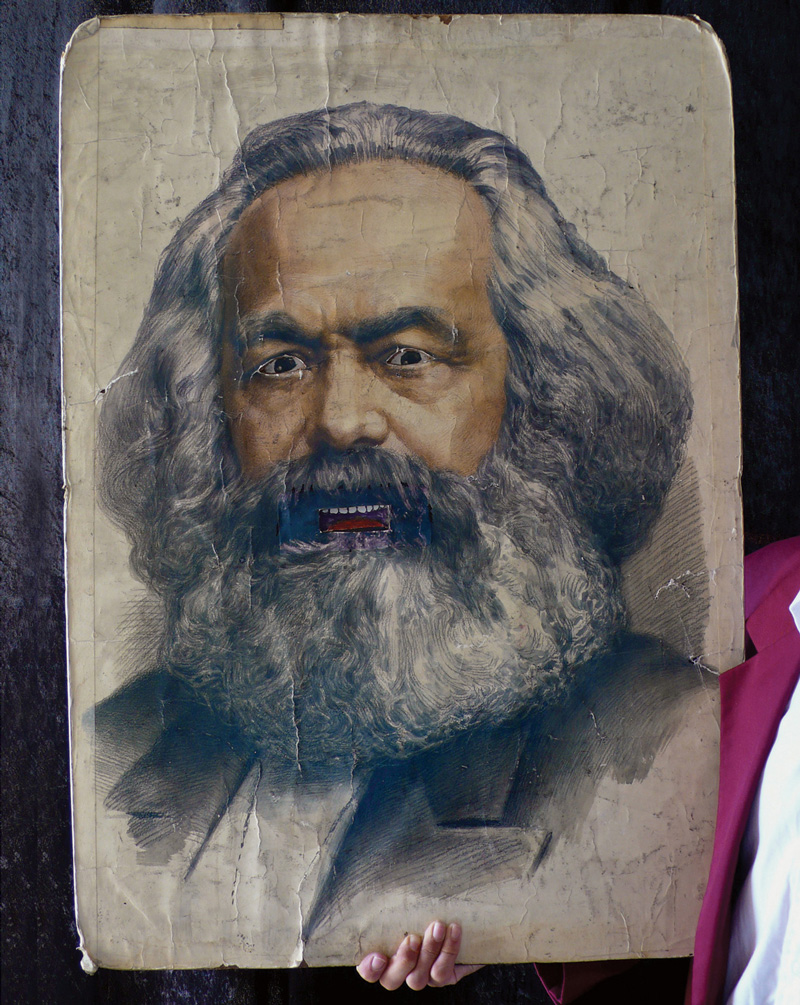

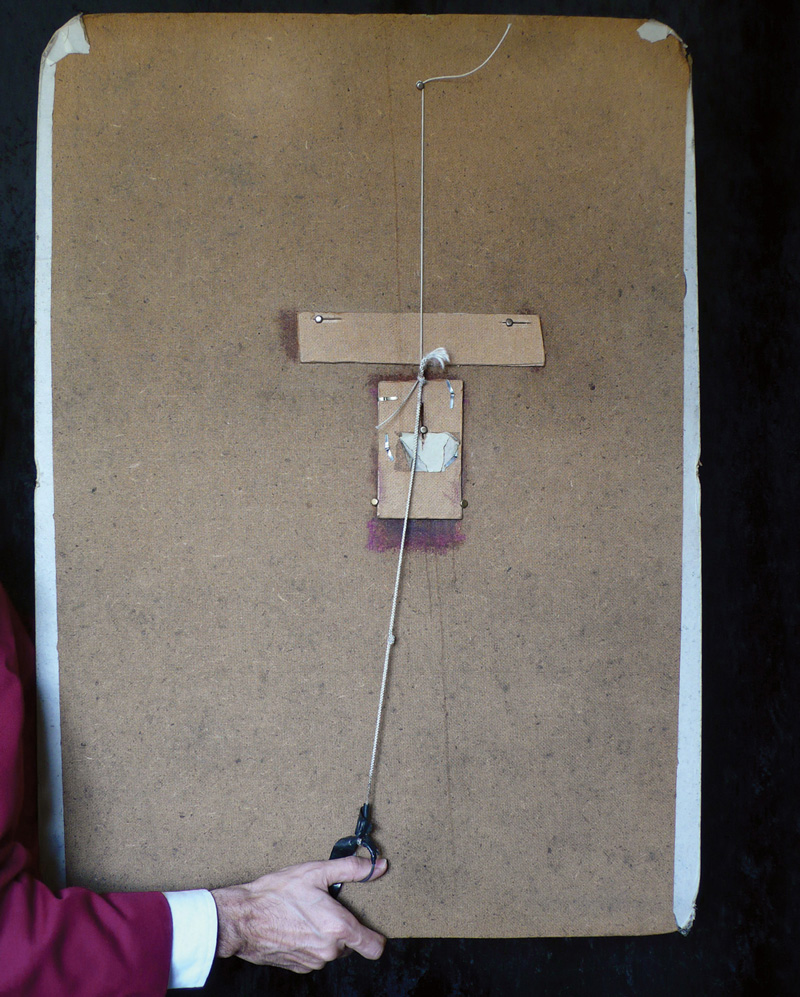

The scene: A windy seaside town in England. An arts festival (entitled, perhaps pretentiously, The Windy Seaside Town Biennale) is in full swing. An audience of skeptical locals, theater-seat-radicals and bloodthirsty performance-art lovers, sated after fish and chips and lashings of warm ale, is watching a man speaking to a picture of Karl Marx. More unusually, the picture speaks back to the man, for this is Ian Saville, socialist magician and ventriloquist, demonstrating his revolutionary art.

At the back of the hall, the art critic Sally O’Reilly watches curiously, almost unable to contain the questions that crowd her mind. The audience is laughing …

IAN: Hello, Karl Marx.

MARX: Hello.

IAN: How are you?

MARX: Not too bad.

IAN: Are you enjoying the show?

MARX: I’m enjoying it immensely.

IAN: Actually, Karl, I was just wondering ...

MARX: Yes?

IAN: If in your day ...

MARX: In my day, yes?

IAN: . … whether you ever had anything like this.

MARX: In what way?

IAN: Well, I wondered if you ever had this sort of socialist culture—socialist songs, music, humor, or even socialist conjuring tricks?

MARX: We had socialist culture, of course.

IAN: You did?

MARX: Oh yes. We had socialist songs, music, humor. All that sort of thing. But we didn’t have socialist conjuring tricks.

IAN: You didn’t?

MARX: No, although it’s a little-known fact that originally I wanted my theories done as conjuring tricks.

IAN: Did you really?

MARX: Oh, yes.

IAN: What was it that stopped you from doing your theories as conjuring tricks, then?

MARX: Engels.

IAN: Friedrich Engels, your collaborator.

MARX: Yes.

IAN: In what way did he stop you?

MARX: Well, I used to come home after a hard day at the British Museum ...

IAN: Yes.

MARX: ... and I’d go into my house. Through the door, of course.

IAN: Yes.

MARX: And I’d go into the living room, and I’d say, “Engels.” (Pause. Louder:) “Engels!” (Pause. Louder:) “ENGELS!!” (Pause:) Because he didn’t live at my house.

IAN: Didn’t he?

MARX: No. He lived in Manchester, and I was in London. So I’d write to him, and in the letter I’d say: “Look here Engels, I’ve discovered this important new principle. We’ve got to get it out to the general public somehow. What about this idea—what about bringing it out as a rope trick?

IAN: And what would his reaction be to that suggestion?

MARX: He’d say something like: “No!”

IAN: He was against the idea, was he?

MARX: He’d say, “No! Bring it out as Capital Volume I, or Theories of Surplus Value, or The Grundrisse, or Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts …”

IAN: In other words, bring it out as a book. He was telling you to bring out your theories as a book.

MARX: Yes. Actually, I was trying to avoid that word. For your sake.

IAN: Anyway, I’m glad you didn’t bring out your theories as magic tricks, because I don’t think you could explore the level of complexity in a rope trick that you could in three volumes of Capital ...

MARX: Yes, I’ve noticed that with your tricks.

IAN: Is there anything else you’d like to suggest to help me with my socialist magic tricks?

MARX: I’d like to say that “all previous magicians have only interpreted the world. The point, however, is to change it.”

IAN: And I’m sure these people will change it. Though not immediately, of course. You see, this show is so effective that sometimes, when I say, “Change the world,” people immediately want to get out there and change things. So they leave. Sometimes even before the show is over. But you can wait till the end. Because you probably won’t be able to get much changed this evening. And tomorrow’s the weekend. But anyway.

Are there any other constructive criticisms you could offer me, Karl?

MARX: Well, what I’ve noticed is that you’ve only dealt with a small part of the picture. I know you’ve done something about class and solidarity, but there’s a whole world of ideas and emotions to be tackled with this socialist conjuring business. I mean, for example, you haven’t mentioned anything about surplus value.

IAN: No, I haven’t. I’ll get onto that straight away.

SALLY: (from audience): Just a minute!

IAN: Excuse me, I’m trying to get on with a show here.

SALLY: I don’t think so. In fact, this is a reconstruction in written form of something that only properly exists as a piece of live performance.

IAN: That’s one of the most pathetic heckles I’ve come across in a long time.

SALLY: It’s not a heckle. It’s part of a critical commentary.

IAN: Isn’t that the same thing?

SALLY: No, criticality takes a position of reciprocity and exegesis in relation to the artwork, not disruption or negation.

IAN: I’m not sure I understand a word you’re saying.

SALLY: You don’t have to understand. This is for the readers.

IAN: The audience.

SALLY: Never mind. What I want to know is: Why are you using magic tricks in this way? Do you seriously believe that illusions such as these can change the world?

IAN: Pardon?

SALLY: (Louder) MAGIC TRICKS—WHY? A SERIOUS ATTEMPT TO…

IAN: Listen, comrade, rather than shouting your remarks from the back of this smoke-filled room, perhaps you could join me up here on the stage.

(Sally steps up. Enthusiastic applause from the now nonexistent audience.)

IAN: Thank you. And your name is …?

SALLY: Sally O’Reilly.

IAN: Do you mind if I call you Rosa Luxemburg, just for the purposes of this next trick?

SALLY: Yes.

Sally O’Reilly is a London-based writer, lecturer, producer of performance based events, and founder of the Brown Mountain College.

Ian Saville has been performing his “magic for socialism” act for the past twenty-five years. He is also an actor and teacher, and has written a Ph.D. dissertation on the history of the British Workers’ Theatre Movement. He works with Forum theatre group Arc, and teaches part-time at Middlesex University, London.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.