Underworld: An Interview with Rosalind Williams

What lies beneath

Sina Najafi and Rosalind Williams

Fascination with what lies beneath the earth seems to have been shared by many different cultures. In the eighteenth and especially the nineteenth centuries, however, the emergence of new technologies made it possible for the first time to dig into the earth on a scale that had been previously unimaginable. Whether undertaken in the service of science or in the name of public works, these colossal excavations dispelled many longstanding myths. Nevertheless, the subterranean imagination did not simply disappear. Instead, it reconfigured itself around a new set of ideas, fantasies, and fears.

In Notes on the Underground (MIT Press, 1990; revised edition 2008), Rosalind Williams, Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science and Technology at MIT, examines how actual and imaginary underworlds shaped our attitudes toward the manufactured environments that we inhabit. Sina Najafi spoke to Williams by phone.

Cabinet: Many of the spaces that you discuss in your book are subterranean, but your discussion extends to some spaces that are in fact above ground, such as malls, or even under the sea, such as Captain Nemo’s submarine. What is your definition of the underground in the book?

Rosalind Williams: The book is a thought experiment in considering the implications for humankind of living in an environment that is predominantly human-built. I use underground environments as a way to think through this question. Some are actual subterranean spaces; some are imaginary underworlds; still others may not be actually underground but are so confined and sealed that they can serve as proxies.

I started thinking about subterranean spaces in this way after reading a core passage from Lewis Mumford’s 1934 cultural history of the machine age, Technics and Civilization, in which he discusses the importance of the mine. Mumford describes the mine as a place where the organic world has been banished. He uses it as a model for environments that are entirely human-built, that are completely artificial. If you look at Mumford’s drafts of the book, you see that he struggles to define these spaces. He ends up using the term “manufactured environment” in quotes, suggesting that he is aware that he’s inventing a term—no standard term was available, which is still the case. There was at that time a standard image of the manufactured environment—the city—but in Technics, Mumford argues that nineteenth-century cities were, in fact and in appearance, extensions of the coal mine. The underworld for Mumford was a more effective image of a manufactured environment since it was far more inorganic than a city.

Back to your question: What is the underworld in my book? In the beginning, I had a straightforward definition: it was a mine, or a pit dug into the earth, or a subway, or a tunnel. As I was writing, however, I realized that one of the most interesting aspects of the world that humans have constructed on the surface of the earth is the creation of mock or artificial underworlds in the sense of places that are meant to exclude organic life, where everything is meant to be a creation of human artifice rather than given from the larger universe. A shopping mall, for example, can serve as a model of a technological environment (a term Mumford didn’t use, but that I find useful) even if it isn’t literally underground.

But most of all I try to expand the concept of the underground from the earth to the sky. I end the book by comparing environmental consciousness with subterranean consciousness, pointing out that the real surface of the planet is the upper edge of the atmosphere. Our earthly home is everything below the frigid and uninhabitable realm of outer space, and so in a sense we have always lived below the surface of the planet, in a closed, finite environment.

Is the underground any enclosed space?

Not really, which points to the limits of the metaphorical use of the underworld. Whether existing or imagined, a truly subterranean space is not only closed but also has an element of verticality. It is the combination of the two that gives the image of the underworld its unique power as a model of the technological environment. If we go or imagine going underground, we enter an environment where organic nature is largely absent, but we also retrace a journey that is one of the most enduring and powerful cultural traditions of humankind: a metaphorical journey of discovery through descent below the surface. Even in places that lack caves, such as the Kalahari Desert and the flat landscapes of Siberia, the preliterate inhabitants assumed a vertical cosmos. Nature was assumed to be as deep as it was high. Narratives about journeys to the world below were inherently sacred. So the significance of the underworld isn’t just as an image of a “manufactured environment.” It is also significant for the kinds of stories people tell about it.

I should add that despite the importance of Mumford in stimulating my thinking, in my studies of the underworld I focus on British and European events and texts. I originally planned to use the American experience too, but the more I worked with American subterranean stories, the more I realized that they did not fill the same cultural role as in the Old World. American writers typically develop the theme of a technological environment on a horizontal plane—the machine invading the garden, and the pastoral “middle landscape,” to refer to the famous work of Leo Marx on this subject. In his view, the horizontal journeys of American literature arise from the unique environmental conditions of the North American continent, where a technically advanced society invaded a continent rich in natural resources and spare in native population. The conditions are entirely different in Europe, where it is much harder to find open land: the vertical journey makes more sense when the horizontal possibilities are much more limited than in the New World.

But you also discuss how this vertical cosmos did come to lose some of its influence.

The idea of a vertical cosmos began to weaken in Europe during the age of the great explorations, between about 1500 and 1700. At the same time, as part of the same gradual process of secularization, the sacred myths that form the earliest content of Western literature began to be displaced by secular narratives, in which an adventurous, unlucky, or half-mad traveler discovers an underworld from which he may or may not emerge. Some, like William Beckford’s Vathek (1787), tap into ancient fears about the underworld (the Caliph Vathek enters into a pact with the devil and visits his Palace of Subterranean Fire). Others are more light-hearted, an example being the subterranean adventure story The Journey of Niels Klim to the World Underground (1741) by the Norwegian Ludvig Holberg, where Klim ends up in the underground land of Potu inhabited by rational, peripatetic trees.

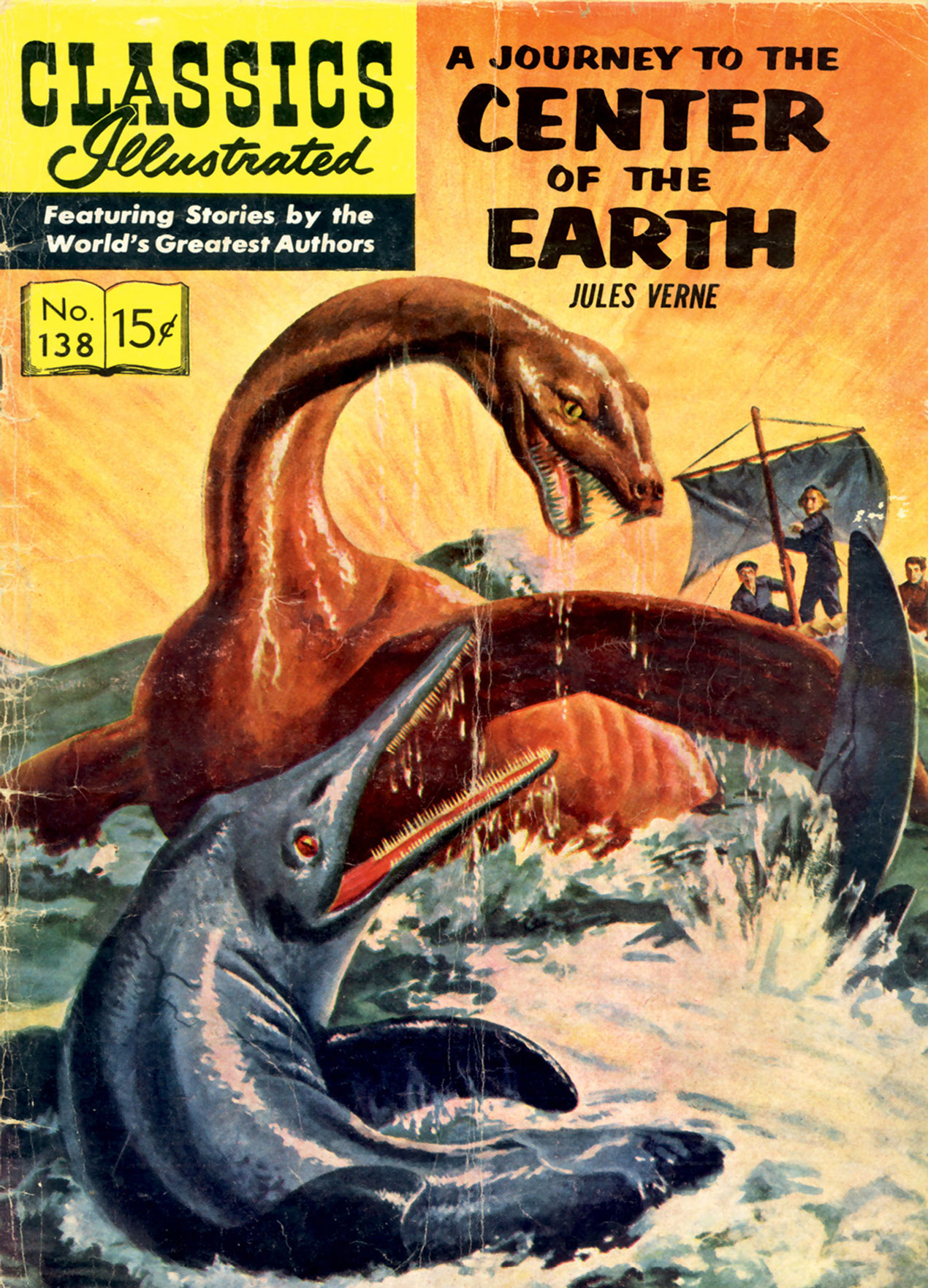

In the nineteenth century, however, another type of story began to be written. Instead of being a place to visit, the underground became a place to live. Instead of being discovered through chance, an underworld could be constructed through deliberate choice. Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) is still an imaginary subterranean journey. Far less famous, but at least as intriguing, is another book he published thirteen years later, Les Indes Noires, which depicts a permanently functioning underground society. This second type of underground tale emerges along with modern science and technology. As scientific knowledge advanced, the idea of discovering a hidden inner world became less and less credible. On the other hand, as technological prowess advanced, the idea of building an inner world became more and more credible.

What is the role of the earth sciences in developing the relationship we have toward the underground?

In Technics and Civilization, Mumford suggests that the mine is also a model for the modern scientific world view. He says it is “nothing less in fact than the concrete model of the conceptual world which was built up by the physicists of the seventeenth century.” This is close to the perspective of Carolyn Merchant in her 1980 book The Death of Nature. According to their common analysis, once nature is subjected to scientific rationalism, it ceases to be a vital source of human meaning and becomes a matter of fact rather than a matter of value. Modern science, they claim, views nature as devoid of any symbolic aura or spiritual significance—not a living world, but a dead mine. According to the pre-scientific world view, the earth was not a neutral resource to be exploited for human benefit; it was a sacred entity. Mining, for example, was an enterprise of dubious morality, comparable to mutilation and violation.

The key figure in the development of modern science is Francis Bacon, and both Merchant and Mumford stress that he used aggressive metaphors of mining and smithing to describe the intrusive activities of natural philosophy. For example, Bacon recommends that researchers should dig “further and further into the mine of natural knowledge.” Merchant rightly emphasizes the aggressive masculinity implied when Bacon writes that “the truth of nature lies hid in certain deep mines and caves” which must therefore be penetrated to discover her secrets.

But Bacon is not all there is to science: there are other styles and traditions that are (in the words of environmental historian Donald Worster) less “imperialist” and more “arcadian.” These other, older, more value-laden modes of thought in fact persisted through the nineteenth century and indeed gained strength over time. Students of the earth sciences may have intended to carry out the Baconian program of value-neutral observations and experiments, but intention is not the same as result. As investigators gradually went deeper and deeper below the surface of the earth, they discovered a world far older and far stranger than Bacon or his immediate disciples ever imagined.

The historical sciences of the nineteenth century— geology, paleontology, anthropology, and archaeology—sought a rational past but as they dug deeper into the earth, they uncovered a quasi-mythological one, which included dragon-like beasts and satyr-like humans. So, for example, when Georges Cuvier carried out extensive investigations in the Paris Basin in the early 1800s, he developed principles of comparative anatomy so that extinct animals could be reconstructed from fragmentary remains. Many of them were strange and frightening: mastodons, cave bears, rhinoceroses, and crocodiles. Even more startling discoveries were to follow, especially in 1857 when a human-like skeleton was found near the Prussian town of Neanderthal. The skull, with its low forehead, large ridges above the eyes, and thick bones, seemed to hark back to ancient stories of centaurs and satyrs and other semi-human creatures. The last decades of the nineteenth century brought a whole series of fossil discoveries, the unearthing of quasi-mythological sites—Nineveh, Crete, Ur, and above all Troy—all of them revealing strange and wondrous objects. Part of the cultural impact of these sciences was that they came to have the quality of a mythological narrative.

To what extent would a layperson living in a city have known and thought about these digs?

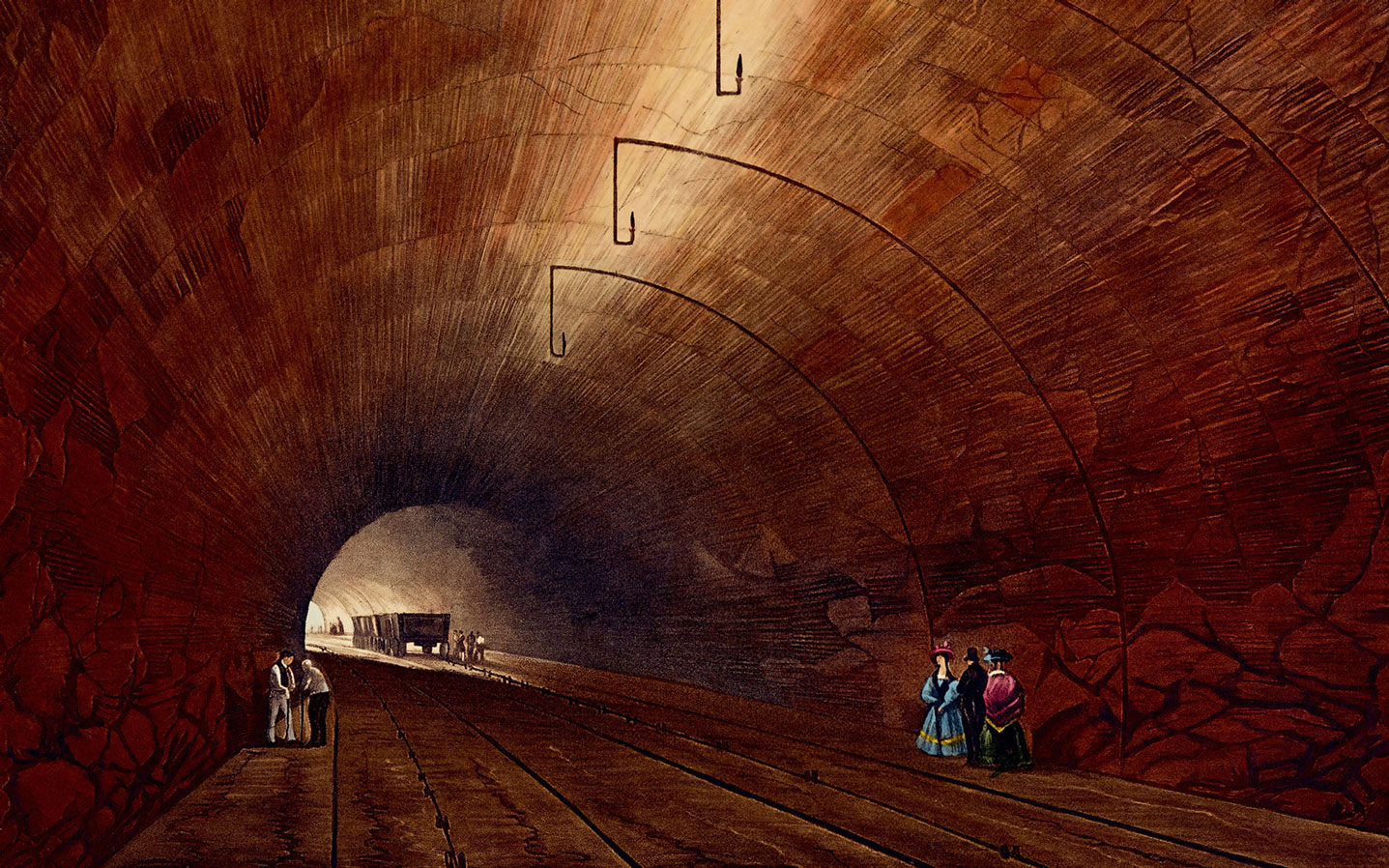

An event like the discovery of Troy, even if it happened far away, was widely reported and certainly entered the imagination of the bourgeois public. After all, most of them were still educated in and through the classics, so a site like Troy connected with their own sense of identity. In other ways, excavation was a public and widely shared experience at that time. Both in the city and in the country, tunneling and digging were occurring on an enormous scale for railroads and subways. The heroic age of transportation tunnels opened with the advent of railroad construction in the 1830s. While traditional overland roads would usually wind their way around any natural obstacles, European railway lines were built on a nearly level grade. This was because the early locomotives had limited power, and also because it cost less. In Europe, land was expensive and labor relatively cheap, and so it made financial sense to construct tunnels, embankments, and cuttings so the railroad would be as short as possible.

The second half of the nineteenth century brought yet more rounds of excavation related to new and improved systems of urban infrastructure: sewers, water mains, steam pipes, subways, telephone lines, and electrical cables. This type of work took place extensively in the Paris of the Second Empire. By the time of the international exposition there in 1867, the new sewer system of Paris had become a common tourist site, recommended by Baedeker and requiring special facilities to handle the sightseers.

In sheer scale, though, the most monumental projects were the subways. Something like four times as many cubic meters of rock and soil were dug up to build the London Underground system as were excavated for the Simplon Tunnel through the Alps. The tools were usually simple ones—spades, pickaxes, crowbars—but they were used on a massive scale and often right in the middle of both major and secondary cities. The deeper tunnels, and those going through muddy and spring-laced ground, required tremendous innovation, not to mention bravery, on the part of engineers and workers who used shields and compressed air to tunnel through soggy soils. Similar techniques had to be used to sink ever-deeper and stronger foundations for ever more ambitious buildings and bridges. You can say that between the late 1700s and the early 1900s, the ground of Britain and Europe was dug up repeatedly to lay the foundations for a new society. It would make sense for readers and writers to connect the new technological infrastructures with new structures of society and consciousness.

Can you discuss the ways in which subterranean fantasies and anxieties were expressed in nineteenth-century fiction?

I was especially interested in two kinds of narratives. In one, the protagonist journeys from the surface down to the underworld and discovers hidden social depths. In the other, the protagonist leaves an oppressive underground community to undertake a personal journey of liberation to the surface. Both these journeys are found in nineteenth-century literature in works by writers like Victor Hugo, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, Gabriel Tarde, and, in the early twentieth century, E. M. Forster, among others.

An example of a journey to the social depths is Hugo’s Les Misérables, where Hugo takes his reader firmly in hand to descend into the sewers of Paris to become acquainted with the social underworld—les misérables—of France at that time. Another prime example is Wells’s debut “scientific romance,” The Time Machine (1895), which imagines that the human race has evolved into two separate races. When the time traveler reaches far into the future—Wells gives a date of 802701 AD—he first sees the above-ground world of the Eloi who are apparently free and happy. The voyager gradually discovers an underground world of Morlocks, enslaved by the Eloi to do the dirty work of machine production. The Time Traveler extrapolates from the distinctions in his own time between capital and labor, the haves and the have-nots, as well as from the tendency to put the ugly parts of civilization underground while reserving the prettier countryside for the wealthy. The twist is that the traveler eventually discovers that the Morlocks are eating the Eloi. The Morlocks get their revenge because their labor has kept them intellectually active, although morally degraded. The Eloi, the leisured elite, have also degenerated, losing intelligence and character. The degeneracy of brutality triumphs over the degeneracy of feebleness. The message is clearly that this division is dangerous for both sides.

What happens to the knowledge gleaned from this journey? Does it lead to political action within the novel, for example when the traveler gets back home?

In Wells’s novel, the Time Traveler gets the hell out of there! The most unforgettable parts of the story are where he leaps onto his machine to escape the pursuing Morlocks, only to end up spinning even further into the future, where, thirty million years hence, he comes to rest on a dying earth, where the sun has expanded but cooled so that there is now a landscape of rocks, stars, an utterly black sky, bitter cold, and absolute silence. So he returns home with a message that class divisions should be remedied—but that ultimately class warfare matters less than the inevitable environmental destruction that will come with the entropic death of the universe.

In the second type of journey, the writer imagines a permanent underworld society that can only function with a high degree of repression and control. The journey is an escape to the surface of the earth. This narrative is also political, though in a very different sense because this journey is not one of social discovery but of personal liberation. Human life in an enclosed underworld requires a great deal of control to function: resources are limited, and so desires, including sexual ones, have to be severely curbed. A revolution would be very dangerous in a closed world. So these underworlds may have a utopian intent to them, but they are hard to read as anything but dystopian.

The best example of a journey of personal liberation to the surface is in E. M. Forster’s short story “The Machine Stops” from 1909. It’s a prescient story of life underground controlled by a Machine that very much resembles a computer—it is a black box with no visibly working parts that nevertheless controls everything. People in this society have to adjust their lives, rhythms, and desires to the Machine to keep the underground environment functioning. In Forster’s story, the young protagonist Kuno feels constrained and unhappy in the confines of this underworld and begins to train his body for a perilous journey to the surface. After great effort, he climbs through a dark shaft leading from a railroad tunnel, opens the pneumatic stopper that keeps the outer air from the underworld, and emerges above ground in a grass-filled hollow in Wessex. The Machine’s wormlike Mending Apparatus eventually drags him back down to his room. But soon the Machine itself begins to break down: the underground slowly falls apart and is then completely destroyed when an airship crashes into it.

Not the Forster that usually comes to mind! What are the politics of this story?

Forster draws it to a close with the comment, “Humanity has learnt its lesson.” The lesson is that the life of the Machine is the enemy of human life. People need to love their own physical being and also the non-human world which they apprehend through direct sensory experience. Detached from the natural order of things, they degenerate physically and mentally. For Forster, a society organized around abstract ideas and machine-aided comforts is the enemy of humanity.

Are these two narratives part of one dialectic?

Both narratives are political but the challenge is to reconcile them: the journey of personal liberation and that of social liberation. Individual writers will emphasize either the realism of the social discovery narrative or the romance of the individual escapee, but the two stories belong together. This is hard to do, but sometimes you see hints of a synthesis. For example, when Forster’s hero Kuno reaches the valley in Wessex, he discovers not only his own physical and moral strength but also a human community that will inherit the earth after the Machine destroys itself.

You discuss the relationship between catastrophe and the underground. The possible catastrophes we face are obviously different from those facing the nineteenth century, but are there also continuities?

In nineteenth-century narratives of the underworld there are two types of catastrophe that send society underground: massive warfare, and an ecological disaster so severe that the earth’s surface no longer supports life. The imagination of disaster has not changed too much. In our own time, the underground is still thought of as a possible refuge from warfare (especially nuclear warfare) and from environmental collapse.

But this place of safety can become itself a source of catastrophe, because if something goes wrong down below, you’re trapped. This takes us back to the mine: all the complicated technological systems for life support must work there, or miners can be buried alive. The paradox is that the built environment itself can be a source of risk. It can fall apart due to mechanical malfunctions as well as social malfunctions such as war, revolution, or terrorism. This collapse can even be welcomed as a return to a more normal or “natural” state of human life, if the built world seems to have alienated human beings from their own selves and from each other. Ultimately, a well-functioning society is our most reliable and effective source of security.

Rosalind Williams is the Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science and Technology at MIT. Her books include Dream Worlds: Mass Consumption in Late Nineteenth-Century France (University of California Press, 1982); Notes on the Underground: An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination (MIT Press, 1990; new edition 2008); and Retooling: A Historian Confronts Technological Change (MIT Press, 2002).

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.