Day-Glo Dreams

The fluorescent revolution

Christopher Turner

The Day-Glo Color Corporation’s trademark hues—Saturn Yellow, Blaze Orange, Aurora Pink, Neon Red, Corona Magenta, Signal Green, and Horizon Blue—have been sold since the mid-1930s as colors of safety. The company’s promotional material at the time claimed that “Fluorescent color is seen 75 percent sooner than conventional colors! Fluorescent color is three times brighter than regular color! Your eyes go back to fluorescent color for a second look 59 percent of the time!” Yet these supposedly life-saving hues—now so ubiquitous that we barely notice the way they clamor for our attention—started life as the colors of death.

The inventors of Day-Glo were Robert and Joseph Switzer, the teenage sons of a pharmacist in Berkeley, California. In 1933, Robert, a nineteen-year-old chemistry student at the University of California, was working a summer job at the Heinz factory when he was found unconscious under a collapsed crate of bottled goods. “I remember waking up in the hospital, looking in the mirror and seeing two left eyes puffed out like ripe tomatoes,” he wrote in an unpublished chronology of his life. “I had a bad skull fracture, heavy internal bleeding, brain damage, a partially severed left optic nerve, divergent left eye, double vision, and extensive loss of memory.”

Joseph, a year younger than his brother but always the extrovert of the pair, had just graduated from Berkeley High School and aspired to be a magician. According to Robert, he was “a master of sleight of hand,” whose favorite stunt was to drive the family’s Model T Ford around the block blindfolded. He was especially interested in the magician’s “black art,” whereby ultraviolet lights (known as black lights) are used to make fluorescent objects miraculously appear and disappear on a darkened stage.

Because of his damaged left eye, Robert had to avoid bright sunlight during his convalescence. His father turned the pharmacy basement into a darkroom so that he would have something to do as he recovered, but he didn’t use it much for photography. Instead, Joseph asked his brother to use his knowledge of chemistry to help him to intensify the fluorescent paints then available so that he might improve his act.

One night, the two brothers explored their father’s drugstore with the ultraviolet light Joseph used for his tricks. Certain chemicals, they were fascinated to see, glowed incredibly brightly under the black light. Murine eye wash was particularly luminescent, and when they mixed it in the darkroom with an alcohol solution of white shellac paint, the result was their first good fluorescent yellow. Though it appeared white to the naked eye, under UV lights it shone with the intensity we associate with its visible successor: Day-Glo.

When a performer at the annual convention of the Pacific Coast Association of Magicians dropped out at the last minute, Joseph was invited to take his place. The brothers worked around the clock to fashion a costume and headdress from several hundred bits of paper that were heavily coated in the Murine-based dye.

“In its presentation, the Balinese dancer appears out of a dark stage in a flash of brilliant light and dances in an exotic manner to fitting music,” the brothers wrote of the act:

For a thunderous climax, she twists her body in agony and upraises her spectacular glowing hands with long fingernails as her head is slowly raised from her shoulders. [The fluorescent head was removed by another dancer, hidden behind the first in a black body suit.] She continues to dance but slowly falls to the floor, her severed head following her about in a most startling manner. Suddenly the stage is dark.

Joseph won the prize for the convention’s most outstanding effect, and the brothers began to sell his illusion. A letter addressed to one Kleeland the Magician offered it “packaged in a small bag” for $75. In later productions, the brothers introduced a fluorescent sword to decapitate the Balinese dancer and squirted fluorescent “blood” from the hole in her seemingly gaping neck.

In 1934, encouraged by their early success, Joseph and Robert set up the Switzer Brothers’ Ultra Violet Laboratories. Despite the grand name, their business was a homey affair. The laboratory was their mother’s laundry room, their tools her “Mix-Master” and other kitchen utensils. They charged the princely sum of $10 a pint for their special Glo-Craft paint (it was so expensive that customers suspected that it must contain radium). However, they were such perfectionists that they offered to custom-engineer each installation for free.

• • •

The paint, invisible except in ultraviolet light, allowed one to imagine an alternative ghostly universe beyond the color spectrum that could be summoned up at the flick of a switch. As a result, many of its applications—as with the headless Balinese dancer—gestured towards the macabre. Fluorescent paint, it seemed, was the perfect medium for representing death. One theater, for example, used it to paint skeletons on the costumes of a line of chorus girls, so that when white lights were alternated with black lights, the dancers seemed to move in unison like an X-ray image of themselves.

The Switzer brothers sold their paint to spiritualists, who used it to paint messages on drapery and fool their grieving customers into thinking that they could summon up images and messages from beyond the grave. (The brothers worked as consultants to ensure the drama of these effects.) The spiritualists also treated cheesecloth in the paint so that the ectoplasm that spiraled out of their mouths in the darkness of the séance would seem even more ethereal and strange. The lights that the Switzers used in such installations were slow to warm up, but even this limitation was put to use. The ectoplasm was only faintly visible at first, but when the lights heated up, it glowed with a weird, unearthly intensity.

Morticians were also among the Switzers’ first customers. When undertakers prepared bodies, they would mix the fluorescent paint with embalming fluid so that they could tell when the liquid had been evenly distributed around the veins. Under ultraviolet light, the successfully treated corpse would glow as if it were radioactive.

• • •

In the fall of 1934, a private detective turned up at the Switzer home looking for the “Schweitzer brothers.” It was a scene straight out of noir cinema. He had been hired to track them down by Leonard S. Smith, president of the National Marking Machine Co., who wanted them to develop a range of invisible laundry marking inks. The brothers, not yet twenty-one, moved to Cincinnati, where they managed to come up with three colors of the required inks. These could resist cleaning and the heat of ironing, would be visible to sorters under ultraviolet light, and would fade by the time the clothes returned to the laundry for another washing.

The Fantom-Fast system, as it was known, remained in use until the 1950s when detergent companies started adding fluorescent materials to improve the whiteness of laundry and made the invisible ink ineffective. Each laundromat was assigned a number, and each customer an exclusive prefix, which was stamped in large letters on all items of clothing. “We had an invisible locator code which crime detection agencies used very successfully in tracing the movement of baffled crooks, who believed their laundry was not marked,” recalled Robert Switzer. “We understand that invisible laundry marks played an important role in the final tracking of the gangster, [John] Dillinger.”

Sadly, this wonderful story is apocryphal—the legendary bank robber was gunned down by the FBI on 22 July 1934, but the Switzers only began work for Smith the following year. The myth might have arisen because the agent who meticulously recorded Dillinger’s possessions when he died noted that he was wearing a pair of gray pants, laundry mark number “355 (40).” Even if the Switzer brothers didn’t help catch Dillinger, by the 1940s most police forces maintained a “Laundry Mark and Dry Cleaners File” so that, if an article of clothing was left at the scene of a crime, the owner could be quickly traced. The Switzers’ innovation was to make the existence of such marks unknown to anyone other than the laundries who held them up to the lights. They later sold their invisible inks to the Department of Justice.

• • •

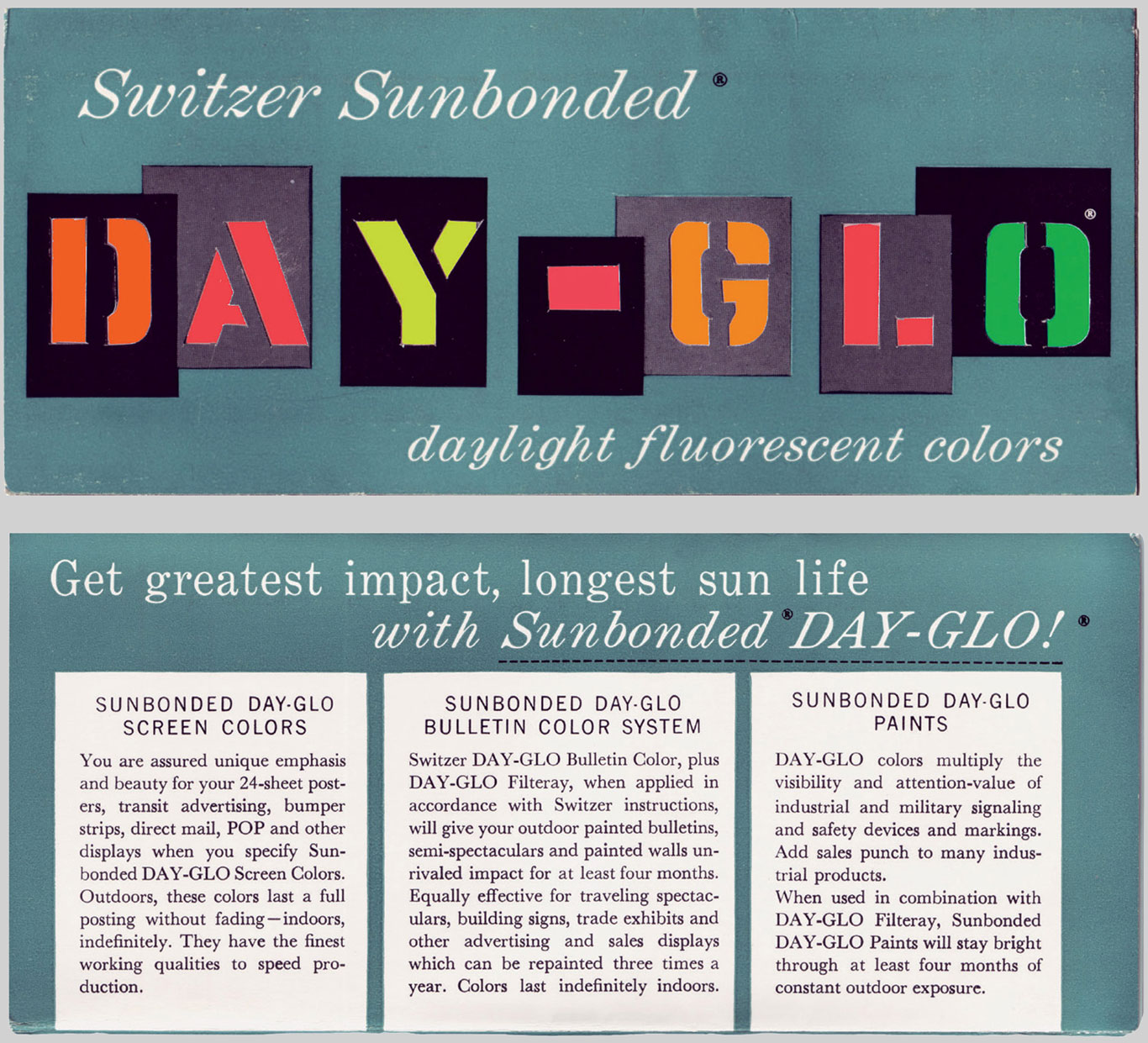

In the summer of 1935, the brothers moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where the Day-Glo Color Corporation is still based, to work for a subsidiary of Warner Brothers. Theater foyers were especially suited to the hologram effect of their “Midnight Paintings,” whereby a scene would change dramatically with the shift from white to black light, but these effects worked less successfully on billboards or in windows, where there were contaminating light sources and the colors were liable to fade. The Switzer brothers began to search for a luminous paint that was visible to the naked eye, and in 1936, by mixing fluorescent and natural pigments, they successfully created the first Day-Glo lithographic inks, available in a range of psychedelic colors (the radiant quality of the colors was a result of the chemical conversion of ultraviolet light into visible light within the pigment itself). “Switzer Sunbonded Day-Glo” was first used on lobby cards to advertise films.

Around this time, they experimented with creating Day-Glo fabrics by boiling swatches of the wedding dress worn by Robert Switzer’s wife in an alcohol solution of rhodamine dye and white shellac. “They were newly married,” said Robert’s son Paul Switzer in a phone interview. “My father desperately needed some material to test his inventions on, and he convinced my mother to let him borrow her wedding dress—she wasn’t going to wear it again. It constituted the first testing of daylight fluorescent pigments.”

The US military spent $12 million on Day-Glo fabric during the Second World War, making the Switzer brothers rich beyond their dreams. Fluorescent safety materials were first used in the deserts of North Africa so that ground forces could signal to Allied dive bombers and avoid friendly fire; fluorescent paddles were used on aircraft carriers to help planes land in low-visibility conditions and at night, something that Japanese pilots were unable to do. Training aircraft were painted Blaze Orange to avoid mid-air collisions.

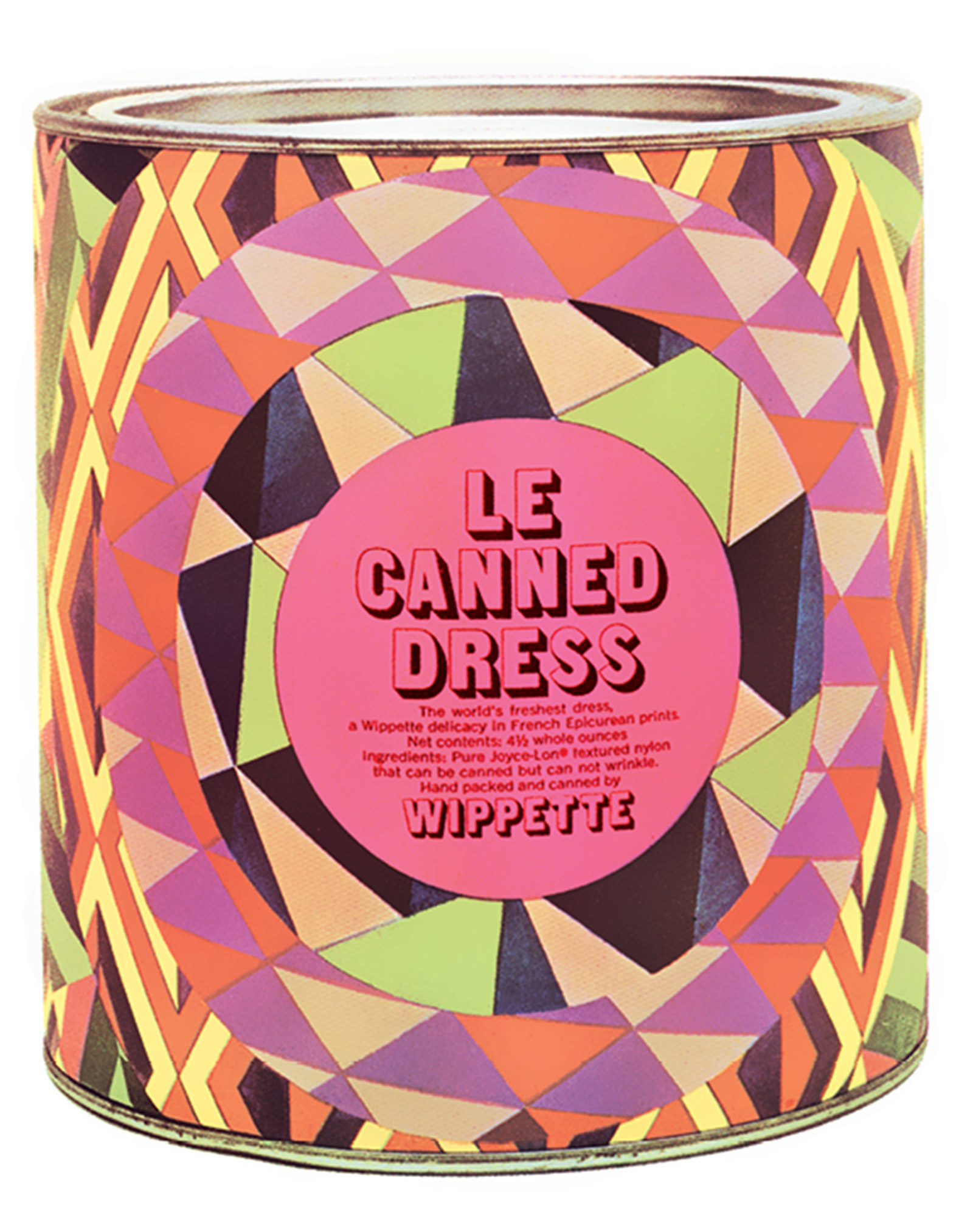

After the war, the Day-Gloification of the world began in earnest. By the summer of 1951, Time noted that “by last week, adolescents were fluorescent from coast to coast, as Switzer’s ‘Day-Glo’ clothes became the newest fad”:

Items: shocking pink caps with kelly green brims, electric blue ties striped with cerise, black cowpoke shirts embroidered in fluorescent green. Some youngsters wore one sock of glowing orange, one of rasping raspberry, topped them off with high-visibility shoelaces in contrasting colors … women were buying brilliant tangerine panties; matching illuminated brassieres were on the way.

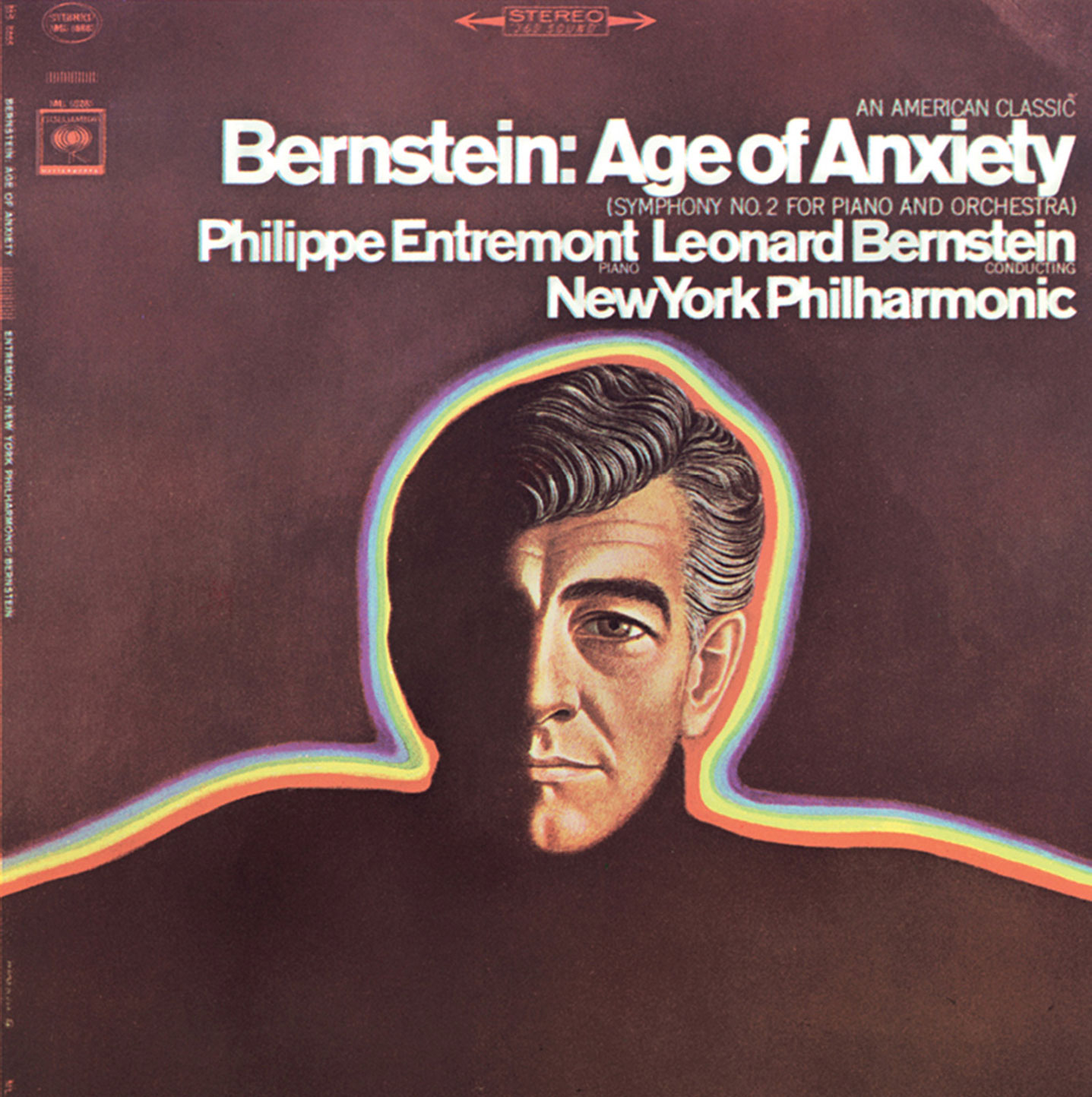

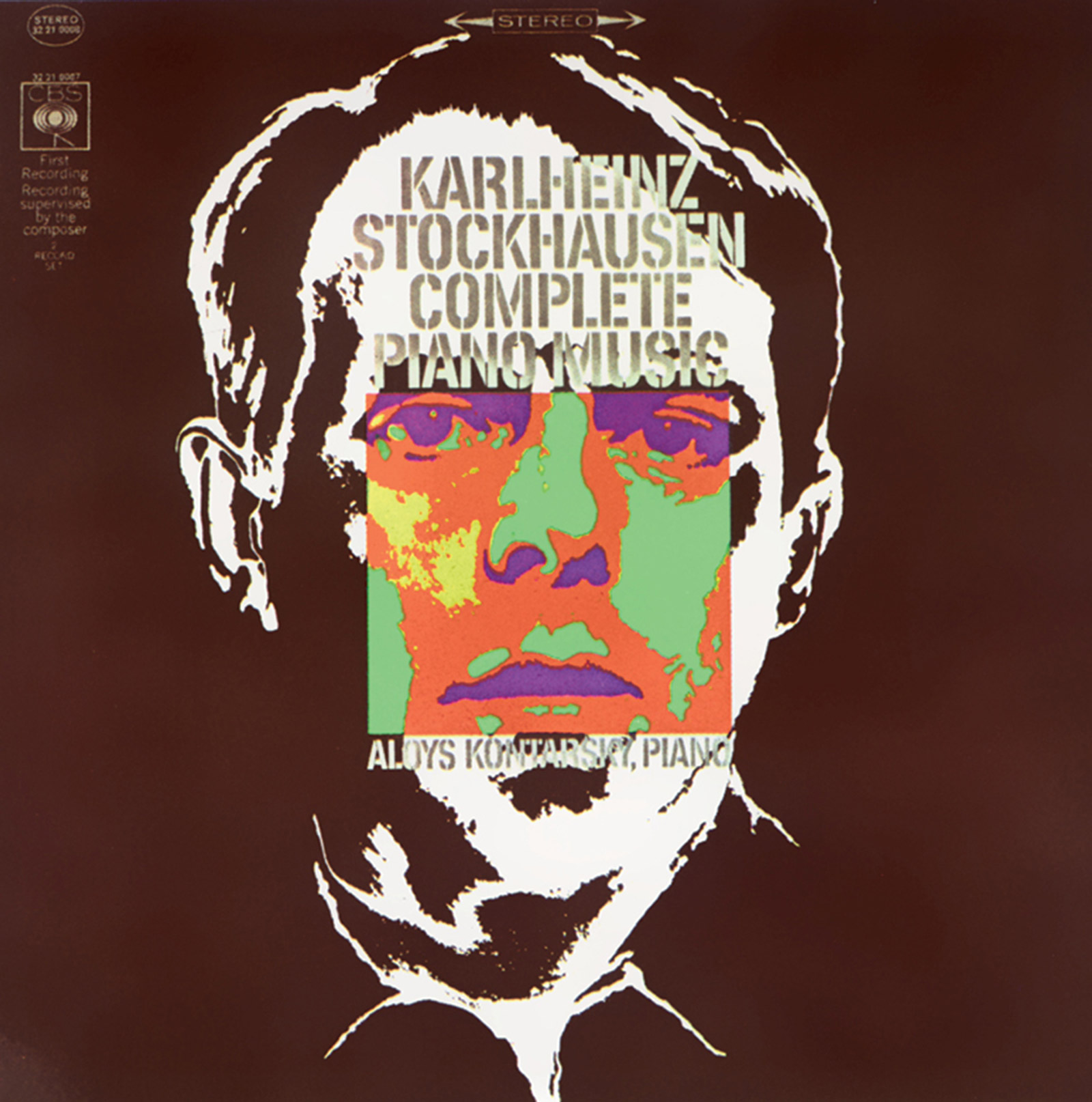

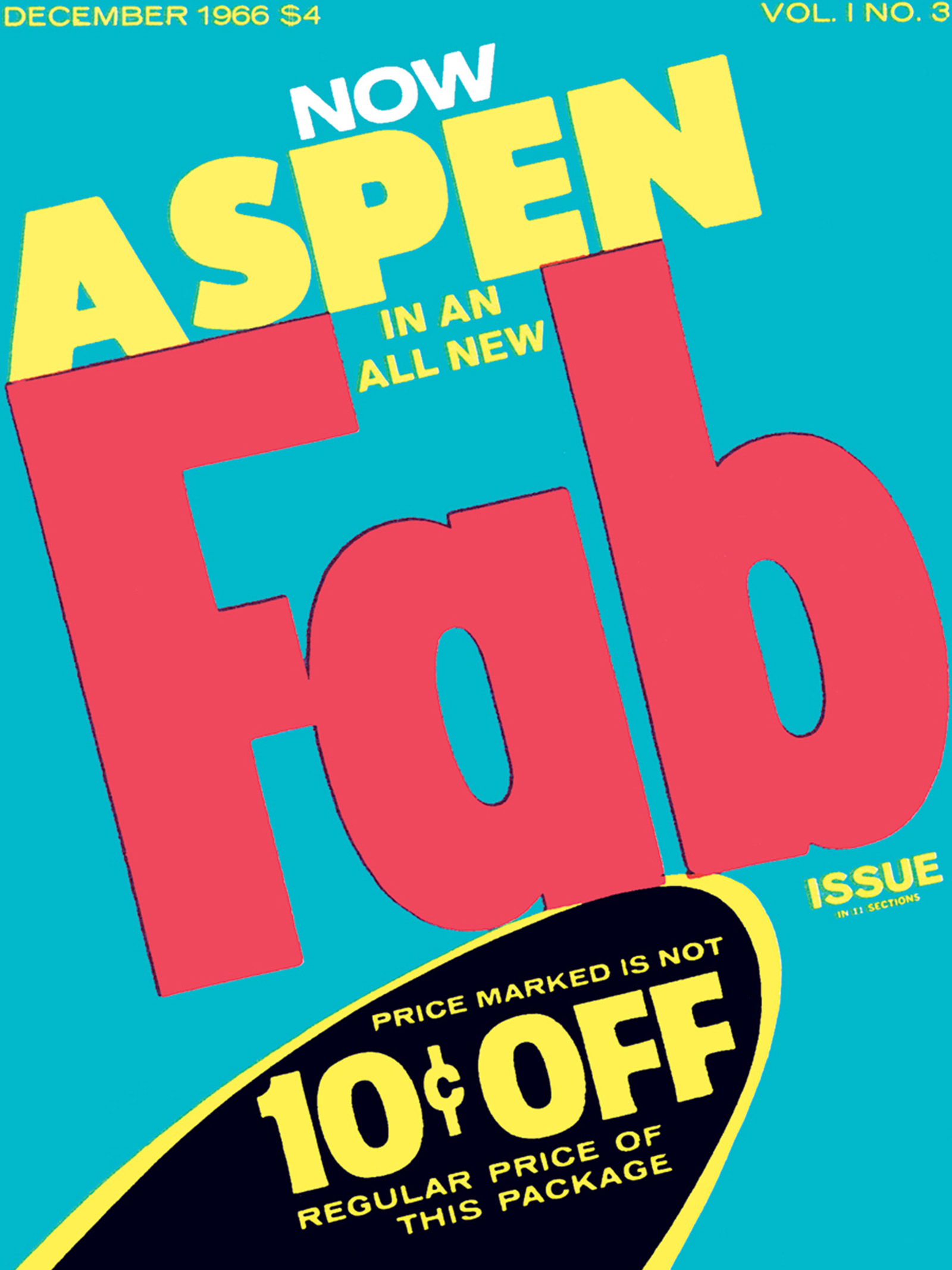

Subsequently, hippies, pop artists, and punks all staked a claim to Switzer colors. Fluorescent dust spewed out of the smokestacks of the company’s busy factory in Cleveland, turning the city Day-Glo. Paul Switzer remembered: “My father used to have many complaints from the residential neighborhood because, for example, all their laundry had been contaminated with fluorescent orange.” The dust was toxic—Day-Glo’s secret recipe used to contain formaldehyde, a carcinogenic ingredient that may have been a hangover from their work with embalmers. In the late 1970s, when Robert Switzer became a keen environmentalist, special filters were put on the factory chimneys to minimize pollutants.

Joseph Switzer, who never lost his penchant for showmanship, wore suits made of fluorescent satin and drove a Ford Thunderbird painted in Day-Glo. He looked less like an industrial entrepreneur than one of Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters, whose legendary bus was also decorated using the Switzers’ invention. Even the introverted Robert, whose preferred attire was checkered jackets and bowties, could not resist the occasional opportunity to flaunt his newfound fame. In Paul Switzer’s recollection, “he was a somber businessman most of the time, but every once in a while he’d dress up and go to a little party as a Day-Glo pirate.”

Joseph Switzer died in 1973, at the height of the Day-Glo era, and Robert, who sold the company twelve years later, died in 1997. When he looked into his grandfather’s open coffin, Paul’s son Peter Switzer was saddened by the fact that “he had nothing that resembled Day-Glo with him.” “So,” he said, “I went up to the priest right before they sealed the casket and gave him a fluorescent golf ball and asked him to put it in with him, and he did. It was Saturn Yellow. I wanted him to have fluorescent colors with him for eternity.”

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.