Gallery of Shooters

The assassin, the non-assassin, and the shape of history

Joshua Dubler and Andrea Sun-Mee Jones

In the half century since the image was shot, shock has bled to lamentation, mourning into melancholia. One feature of the collective fixation with the Kennedy assassination is the conviction that through his action Oswald accomplished nothing less than the derailment of our national destiny. At this moment of rupture, the narrative of American civil-sacred history gives way to impossible speculation. Oswald, as the story goes, ruined everything. On the far side of the fall, we—those on the left especially—are left to forever wonder: where would we be if JFK or, only a few desperate years later, MLK had not been assassinated? What would the world be like had these crusaders been able to complete their holy missions? Regrettably, ours is Oswald’s world, James Earl Ray’s world—the shattered world in which the progressive vision for the United States is achieved only counter-factually, the promised land of social justice reached only in the saddest of tenses: what could have been.

The magnitude of the loss indexes the perceived greatness of the men taken. If, in 1806, Napoleon was “the soul of the world,” ushering history atop a steed, in 1963, it was JFK, journeying prophetically in a Lincoln. On account of his recognized genius at moving men, the great man is regarded as the rightful blazer of history’s trail. In the landscape of American collective memory, King and Kennedy are such giants—men with the vision to imagine a world different than their own and possessing of the skill, will and moment to bring that vision to life.

When considering individual agency in history, however, the great man is not quite as formidable as the assassin. Lacking a similar pedigree, without genius, devoid of any claim to greatness—the assassin, by means of his volition alone, is credited with derailing the intended course of history, shanghaiing us onto a dark track better left untrod. With a slight movement of his finger, LHO rubbed out not just Kennedy but also the history that would have been written. A lazy man’s creativity, perhaps, but the assassin’s destruction shapes the world no less than the great man’s accomplishments. As a parasitic potentate, the assassin seizes the might of the great man, performing a heist of historic proportions. And in the calculus of effects per action, the assassin’s agency quotient towers over that of his foe’s. What takes the great man a lifetime of deliberate labor, the assassin wills in an instant. Assassin: triumphant.

The assassin, no doubt, is defined by his prey, with only heads of state and the infrequent politicultural icon qualifying as victims of sufficiently historic magnitude. In the execution, however, the assassin practices a taxidermic artistry. Because a vicious demise serves splendidly to enhance the hero’s valor, assassination not only derives from but also contributes to the perceived power of the victim. If one ought not speak ill of the mundanely dead, then the prematurely erased command nothing short of adulation. Oswald thus “polished off” Kennedy doubly: he both felled the man and gave him a pleasing texture. In violence and in death, JFK attains monumental stature, ascending to become the structuring principle of ruminations on the ruins of the once new frontier. Underwritten by the assassin, the hero’s debts are forgiven and his glory guaranteed.

The crime is dual. The slaying of a man, as John Wilkes Booth explains to Oswald in Stephen Sondheim’s musical, is a tawdry offense, but assassination is a historical exploit. Absconding, it seems, with the agency that was Kennedy’s birthright, the slender, inconsequential Oswald swells to larger than life—certainly larger than his own life would afford. In his purloining of JFK’s potency, Oswald becomes Kennedy’s monstrous double. After all, it takes a Moriarty—the “Napoleon of Crime”—to slay a Sherlock. Narration demands a worthy nemesis, so the legatees of a historical break must inflate Oswald’s own stature. As Norman Mailer argues, we simply could not stomach the meaninglessness that would chronically reflux if we were to deem Oswald but an ordinary man.

In the fusing of fates that is assassination, both parties enter legend in grandiose fashion. But one will live forever in infamy; for although the hero proves a hittable target, the assassin is ever more so. While the hero plays the part of the victim in the historical text, the assassin is the victim of the historical text. Assured an eternity of character assassination so that Kennedy might rise posthumously, Oswald compensates for JFK’s bath of purification with his own perpetual putrefaction. Not only did LHO—if but for one fleeting moment—become history incarnate but, like Judas’s forfeit for the universal kingdom of the Christ, Oswald’s unredeemed sacrifice makes him the unacknowledged crown prince of Camelot.

In the vortex of medicalized interiority, the assassin is nothing if not pathological. Whether he heeds the call of anarchy, vanity, or the voices in his head, the assassin’s motivations can only be reduced to something else. Even an assassin’s most idiosyncratic fixation (to impress Jodie Foster, for example) can be lumped together with a more general and generic madness. It is therefore the task of court-appointed psychiatrists, armchair anthropologists, novelists, conspiracy fetishists, and, of course, Warren Commissions to deduce that there is something fundamentally queer about Oswald. To apprehend him we must recall that, in his unreasonableness, he is not like the rest of us: “a motive that appears incomprehensible to other men may be the moving force of a man whose view of the world has been twisted.”[1] To understand that his reasons are merely rationalizations—that is what it takes to properly understand Oswald.

To start, a blunt instrument will suffice. He is naught more than the sum of his eccentricities, with details fleshed out as they emerge through analysis: an overly intimate yet negligent mother + resentful Russophilia + retributive matrimony = a pervasive “hostility to his environment.”[2] Oswald might talk of revolution, and when he does, we will jot it down in our notebook, but when we have finished psychologizing him, this quixotic Cold War loser, he will bear little family resemblance to Jefferson or Lenin. In light of his aggressive action, an assassin can at least be charged with a penchant for violence and antisocial behavior; at its most satisfying, the diagnosis will point to full-blown psychosis. Beginning with the premise that a dead president cannot be adequately justified, the assassin cannot hope to be understood as a rational actor, a Kantian autonomous will. The tautology makes it so: the assassin cannot have been acting rationally inasmuch as he performed an action that a rational man would not have undertaken.

Having emptied the assassin of autonomy, the cavity may now be filled. Laid bare on the examination table, Oswald’s lean remains provide ample quarters for a conspiracy. Of course the autopsy report intimates nothing of the kind, but one nonetheless longs to find a master homunculus animating this puppet of a man. Although neither the Cubans nor J. Edgar Hoover nor Lyndon Johnson sprang definitively from the carcass, there have been myriad attempts to place one or all of them at the scene. Efforts to extract conspirators from under Oswald’s pelt recall Walter Benjamin’s story of an automaton that plays an indomitable game of chess. Secreted within, though, is a dwarf of game-playing genius, constricted by the dummy’s form in order to generate a façade of independence. The assassin is the mimetic puppet—not autonomous, rather a mere automaton—a mediocre medium for any sovereign agile enough to zip himself inside.

Like the orientalized Assassins, Oswald was an outcast, a patsy par excellence. The Assassins, word of whom was brought back as Crusader plunder, were youths of the Dark Ages reared by the Old Man of the Mountain, then cast out from the palace and compelled to kill via promises of regaining paradise lost. As the expendable appendages of a stratagem beyond their control, the Assassins were hollows of desperation, artfully hoodwinked into doing their abuser’s bidding unto their own destruction. In this version, the assassin is an agent, to be sure, but an agent precisely in the sense of acting out the aims of another. He is a dupe. No longer the mirror image of the heroic noble, this is a creature so forlorn that it brutally attacks at the behest of anyone who pays it some small mind. This assassin is no candidate for culpability; rather, he descends to the category of a child or non-human animal—those we might forgive only because they know not what they do. Beyond praise and blame, though perhaps not pity, the abject assassin is infected by insanity or, if we’re feeling especially generous or lazy, by the false consciousness of a brain-scrubbing ideology. Trodden into mangy form, crippled by disenchantment, forsaken, the assassin is a victim, a casualty of the cold world, of a culture that promises a junior executive position, at least, but delivers opportunities only in sheet metal or book depositing. Like the Assassins before him, Oswald is regarded as intoxicated by illusions, a docile body at the disposal of some alien—or possibly the general—will. Perhaps the pawn of a conspiratorial chessmaster, or maybe—as Malcolm X would have it—an expedient roost for the chickens of a culture of violence, Oswald was an instrument, a void of pathos where the brutal shades of the American Dream could take up residence. Even at his grandest, Oswald was no historical personage; he was merely the fatal symptom of his time.

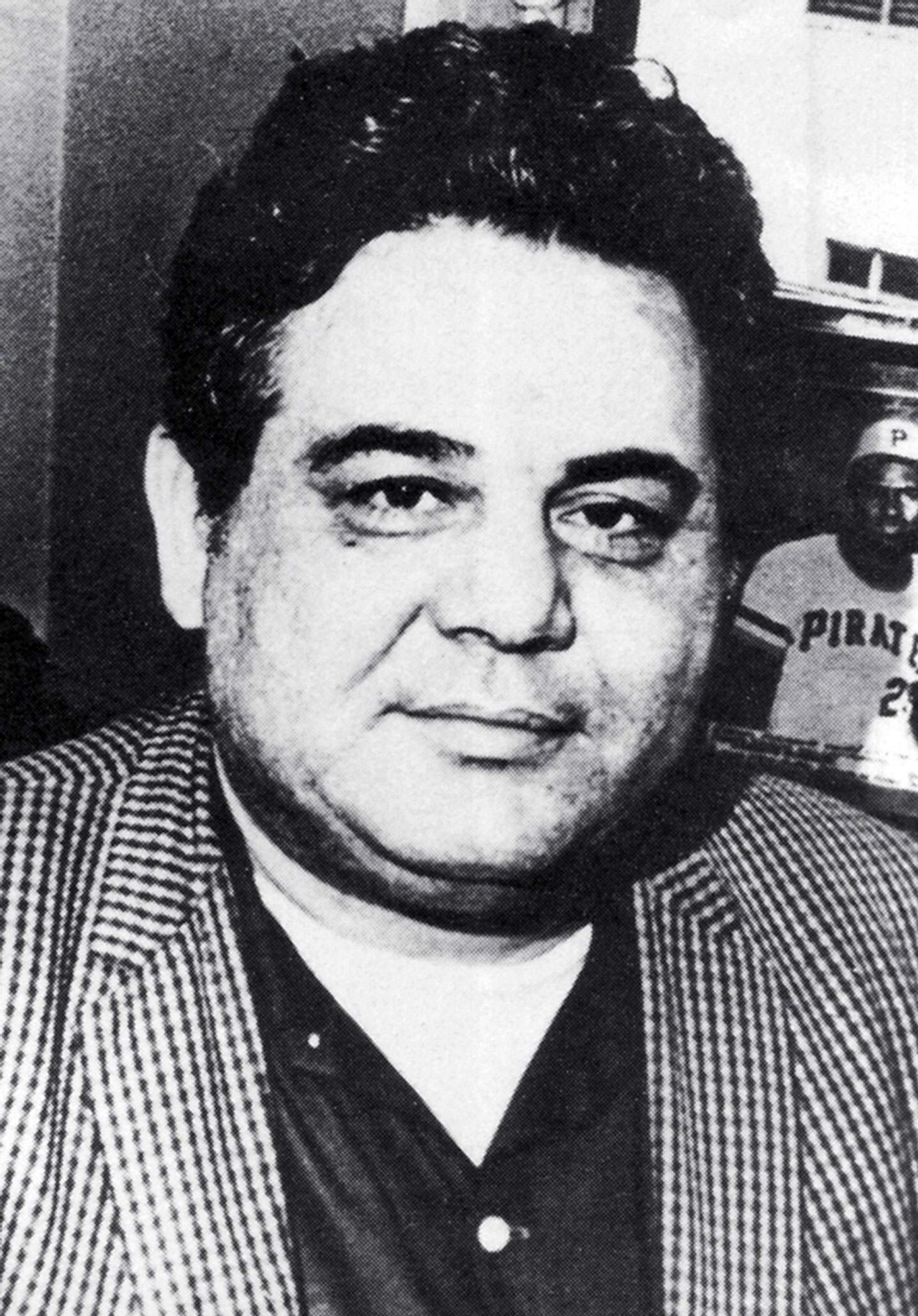

As with Oswald’s second incarnation, Samuel Byck is ripe for psychoanalysis. With such a paltry body of work at the surface level of action, he offers the psycho-dramaturge little option but to plumb his depths in search of those elements that make narrative worth narrating. Just as surely as the Marxist ferrets out class struggle and the Nietzchean mines the will to power, in Byck’s file the Freudian unveils the telltale symptoms: manic depression, grandiose delusion—which is to say, pathology born of pathos. While not wholly unlikable, as a professional and as a family man he is a failure. After a lifetime of urban poverty, a tour in the service, and a return to frustrated obscurity, the denial of a government-backed loan for his automotive business is thought to have driven him over the edge. Quoting an Italian World War I mantra (later adopted by Mussolini) onto a master audiotape, dubs of which he would soon send to Leonard Bernstein and Benjamin Spock, among others, Byck asserted that he “would rather live one day as a lion than a hundred years as a sheep.” With Oswald surely not far from his mind, on 22 February 1974, Byck launched “Operation Pandora’s Box,” drove to Baltimore/Washington International Airport, and boarded a DC-9 with designs to crash it into the White House. This effort was also an abject failure. Byck killed a police officer, the copilot, and himself. The plane never got off the ground.

Perhaps there is an icon here, albeit unpictured. As suggested by Sean Penn’s portrayal in the 2004 Assassination of Richard Nixon, that icon is Willy Loman. Especially as a copy, Sam Byck is truer than the original. As Byck might still be heard saying through the very same medium that brought down his famously tricky quarry, “One grain of sand, any individual—be he rightist, leftist, deranged, whatever he may be—has within his power, his willpower, to cause havoc amongst the leaders of any nation of the world. … I’m only a little ant amongst billions of ants in this world and I’m sure that my life and my death can have meaning.”[3] Byck’s hunger for meaning, for historical effectivity, is poignant in its pathos. More than Loman, Byck represents the curse of the common man; though tragedy in the Broadway debut, it is little more than farce in the rehash.

As failed assassin, Byck is a double trespasser. If the assassin is a poacher of agency, then the failed assassin is twice as undeserving of the right to make history: first, by the poverty of his pedigree and, second, by his bungled execution. Yet, by mustering the requisite historic intention and operationalizing it into a bloody whimper of action, Byck nonetheless qualifies for the pantheon of anti-heroes: James Clarke includes him in his roster of American Assassins, and Stephen Sondheim casts him in the role of tragicomic relief, outfitting him in a Santa Claus hat for two memorable monologues.

Even as a total failure, Byck is endowed with the sacred designation “assassin.” Though the plane never left the tarmac, the hijacking of history was nonetheless plotted. Byck’s flashy exposure of the pivot, the moment when history could have been altered but wasn’t, produces the semblance of an event. If we say without qualification that Oswald affected history by felling the great man, then we may plainly see how Byck affected history by failing to do so. By trying to kill Nixon, Byck provokes the recognition of the counter-counterfactual, which is to say, the (f)actual. An alienation effect is produced in which the unremarkable becoming of history is suddenly rendered visible. No more than a tired tire salesman revealed the ability of the status quo to stay the course in spite of concerted attempts to resist it, disrupt it, propel an airliner into it. Through Byck’s agency, the status quo proves as tenuous as it is tenacious. How fragile is the social order when an unhinged loner has the potential to topple it? How resilient is the social order in its nonchalant accommodation of such attempts? The failed assassination of Richard Nixon admits the conspiracy of force and happenstance necessary for tomorrow’s order to closely resemble today’s. By means of his intention and action, Byck demonstrates how the failed assassin affects history by virtue of his failure to affect history.

Or perhaps the failure was not so comprehensive as all that. As his cameo appearance in the 9/11 Commission Report suggests, even as Byck failed to unleash his intended torrent of chaos, in his reimagination of the airliner as missile, he styled an idiom for later abject heroes to have their say. As with literary output, effects cannot be contained by their generative impulses. Ancillary consequences born of the intentions, as well as the inattentions, of others will always fly the arrow of action off its intended course.

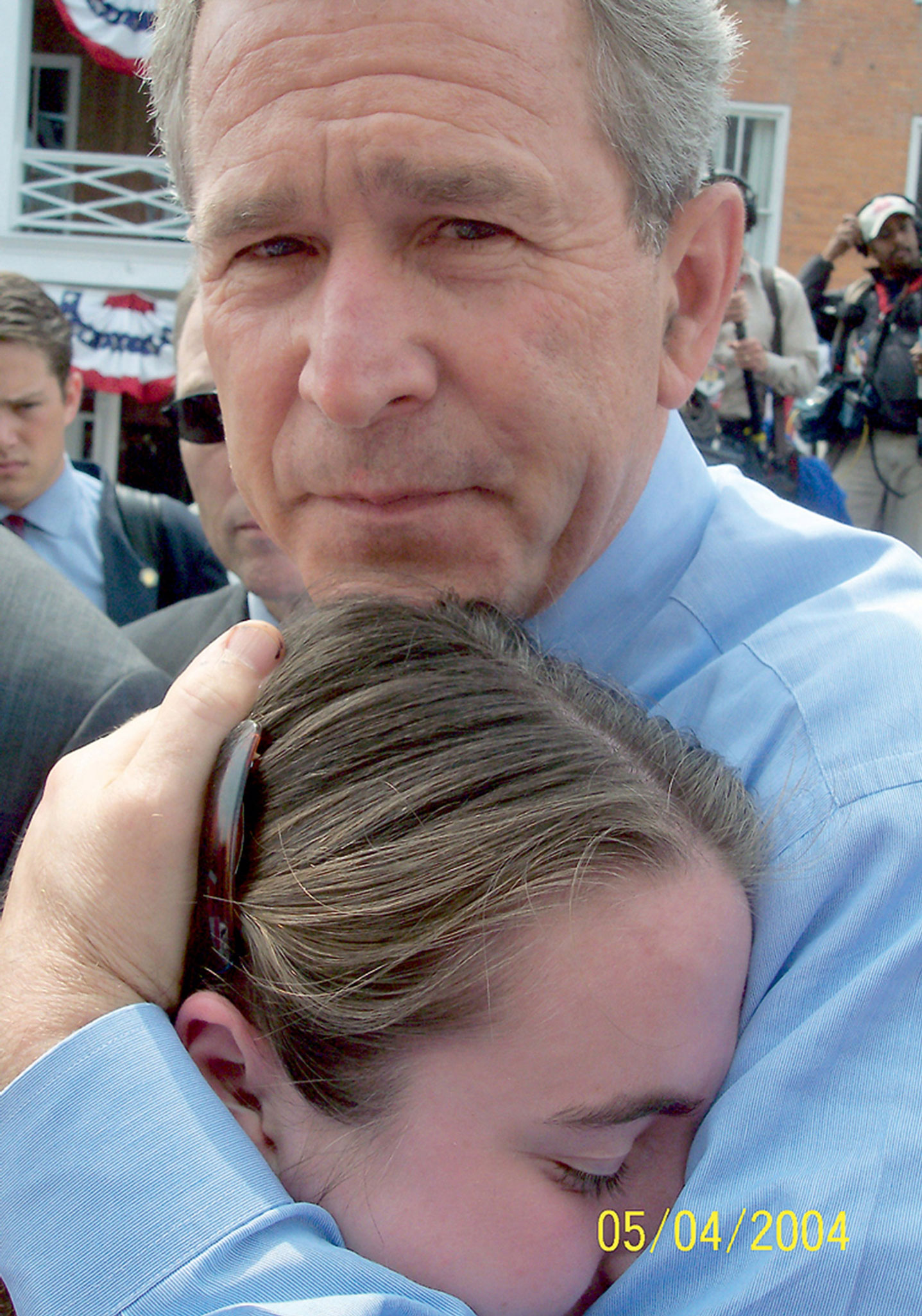

The picture plainly presents the President’s sympathy and allows the viewer to imagine what must have been a cathartic moment of comfort for the girl. Once circulated, the photograph accomplished its blatantly propagandistic function—the branding of the man pictured as the man who cares about what they did, the man who will make you safe. What the image also displays, though it takes a madman’s dose of paranoia to get there, is the critical role played by Ashley Faulkner, the non-assassin, in the making of history. For every one Oswald and ten Bycks, there are a million Faulkners, each contributing to the project of shaping tomorrow in their own small ways. Omissions, in this read, are but commissions by a subtler hand.

If Samuel Byck exemplifies the determinative power of unintended omission—an omission born of assassinatory intention unsuccessfully actualized—then Ashley Faulkner may exemplify a second species of omission: the failure to actualize any intention to assassinate at all. On the face of it, the distinctions between Oswald’s assassination, Byck’s failed assassination, and Faulkner’s non-assassination are obvious; with respect to the place of individual agency in history, however, the three are structurally indistinguishable. Just as Oswald felled Kennedy and shaped history, Byck, by means of his incompetence, and Faulkner, by means of her guilelessness, respectively shaped history by causing Nixon and Bush to live.

Omissions undertaken un-self-consciously are just as crucial, if not more so, to the reproduction of the status quo as commissions undertaken with specified intent. Empowered and constrained by a strand of criticism stretching through Marx, Althusser, and Foucault, our ability to suspend disbelief in a sovereign subject has been impaired. Rather, we would argue, selves are independent, freedom-seeking beings (in the manner universalized by Enlightenment discourse) only to the extent that their conditions enable them to think and not think and act and not act as such. Inasmuch as we are constituted reactively and actively in practice, we live as subjects in the sense of being both the authors of actions and those who are subjugated by the authorizations of others. Which is not to imply that new and unique sentiments cannot be expressed nor unprecedented actions undertaken—but without grammar and syntax, there can be no poetry; without the social structures that render certain possibilities intelligible, there is no meaningful action.

We are all double agents. At what would likely register as our most momentous, we are simultaneously the assassin triumphant and the assassin abject, agents of others no less than agents of ourselves. Most of the time we are perhaps quieter, though no less powerful or agentive. We are non-assassins, engaged in the myriad quiet acts that do not generally qualify for historical recitation.

Momentous action impacting the body of the head of state is but a proxy in this account for countless commissions and omissions, public and private. As far as history or politics is concerned, the many minute, even invisible, actions that make up the vast majority of social practices are of paramount importance. Conditioned responses quickly come to mind (salutation of the flag, utterance of the mea culpa) but consequential also are inactions—abstention from illicit sexual practices, stolidity in the face of poverty. While pound for pound, inaction has a hard time competing for press with a splashy action like assassination, the project of giving tomorrow shape falls disproportionately to these invisible hands. If anything, the not-doings not done for no reason whatsoever are the primary engine driving historical change and stasis. As far as the individual’s agency in history is concerned, every moment finds us peering from a book depository, locked in the comfort of a presidential embrace. We shoot, we misfire, we practice nonviolence, or such considerations never enter our minds—every moment is akin to a historic event.

- Report of the President’s Commission on the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1964), p. 375.

- Ibid., p. 423.

- The Plot to Kill Nixon (The History Channel, 2004), at 54 minutes 45 seconds.

Joshua Dubler is a scholar of religion and a post-doctoral fellow in Columbia University’s Society of Fellows in the Humanities. With Andrea Sun-Mee Jones, he is author of BANG! THUD: World Spirit from a Texas School Book Depository (Autraumaton, 2006). He is writing a book about religious practice at a maximum-security prison.

Andrea Sun-Mee Jones is a writer based in New York City. She received a Ph.D. in Religion, Ethics & Politics from Princeton University, and teaches philosophy of religion at Columbia University. With Joshua Dubler, she is author of BANG! THUD: World Spirit from a Texas School Book Depository (Autraumaton, 2006). She is currently completing a book entitled R/evolution.