The Orchestra

Listening to sirens

George Prochnik

What song the Syrens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, although puzzling questions, are not beyond all conjecture.

—Sir Thomas Browne

In the first years of the twenty-first century, New York City police officers had six different siren noises at their fingertips to alternate and overdub as they attempted to bore through stagnant traffic. The “Yelp” is a high-pitched, rapidly oscillating, jumpy sound that suggests a small dog with large teeth has hold of your thigh and is not about to let go. The “Wail” is the classic keening noise that the Furies might release while pursuing vengeance. The “Hi-Lo,” or “European,” is whiney, forlorn—prone to depression, but undeniably civilized. The “Air-Horn” is vulgarity incarnate—a burp, a rasp, an all-out bursty blast. The “Fast” or “Priority” resembles a hysteric who’s just mainlined crystal meth. The “Manual” is an outcast loner raising its rifle in a solitary low-to-high pulse. The summer of 2007 saw the first broaching of the possibility that a seventh instrument might be added to the ensemble.[1]

The Rumbler™, developed by Federal Signal Corporation, is described in the company’s promotional material as an “intersection-clearing system.” The “revolutionary new concept” behind this technologically simple combo of an amplifier, two high-output woofers, and a built-in timer is the Rumbler’s capacity to interact with most existing siren amplifiers and create secondary, low-frequency tones. A Florida highway patrolman dreamed up the device while listening to the law-flouting, bass-thumping audio on local boom cars. Rumblers copy the primary siren signal, drop the frequency seventy-five percent, then hyperpump the volume. Federal Signal (the defendant in multiple class action suits by firefighters with hearing loss) reports that the depth of bass attained by the system has “the distinct advantage of penetrating solid materials, allowing vehicle operators and nearby pedestrians to FEEL the sound waves.”[2] The Rumbler sounds like a gang of renegade computer games escaped from the screen and storming the streets. 2001: A Space Odyssey meets The Warriors.

When New York City began entertaining the concept of introducing a new siren sound, many had qualms about the Rumbler’s potential to be unduly terrifying. But other police departments around the country, citing the need for stronger measures in an age of cell phone-iPod-AC–cocooned car interiors, began loading the siren and relishing its capacity to bust the bubble. Washington DC police chief Cathy Lanier, head of the first large police force to adopt the Rumbler, remarked, “In the age of technology there’s always something that distracts folks. This helps shake that distraction.”[3] The new siren thus became an interventional tool promoting social focus. Robert S. Martinez, director of the New York City Police Department’s fleet services unit, found that every time he tried out the test model pedestrians and traffic were brought “to a dead stop.”[4] Concurrently, prominent auto blogs began touting the “booty-shaking” effects of the device. One described the gluteal vibration induced by the Rumbler as “the best part of being pulled over.”[5] A public yen for irresistible sensation dovetailed fortuitously with the authorities’ increasingly desperate need to command attention. On 26 October 2009, the New York Times reported that the NYPD had started installing upward of 150 Rumblers into patrol cars. On 27 October 2009, the Times announced that in a recent twenty-four-hour crackdown on drivers’ cell phone use, the department had ticketed 7,529 people, adding that the daily average of cell phone tickets one year earlier had been 536.[6]

Rumbler use continues to proliferate around the country, and these über-sirens are now a standard instrument in the police officer’s sound-mixing dashboard.

The question of the nature of the siren’s face, and of the siren’s true role in human affairs, haunts both the mythological creatures from which the mechanical sirens derive their name and the history of siren technology alike. In a dizzyingly comprehensive account of classical references to sirens, the nineteenth-century historian Walter Copland Perry acknowledged that the overwhelmingly “contradictory” and “enigmatical character of the Sirens” was reflected in “the great difficulty of reconciling the different aspects in which they were presented to us in ancient literature and art.”[7]

The earliest poetic allusion to the creatures appears in Book Twelve of The Odyssey when Circe, charting out the perils for which Odysseus must prepare himself on his return voyage to Ithaca, observes that the first hazard he will encounter is the island of the Sirens. “Whoever draws too close, / off guard, and catches the Sirens’ voices in the air— / no sailing home for him… / The high, thrilling song of the Sirens will transfix him.”[8] Mesmerized, the listener steps overboard into the meadow where the Sirens reside, idling life away while listening to the Sirens’ hypnotic playlist amidst mounds of decomposing corpses. Circe tells Odysseus that if, despite the risks, he should insist on hearing the Sirens’ music, he must instruct his sailors to bind him to the mast and place softened beeswax in their ears. True to the larger convolutions of the siren story, the first recorded use of earplugs, then, was not to protect wearers against an ugly noise, but to stop a sound that was too thrillingly enticing.

Homer’s casual invocation of the Sirens suggests that he was counting on his audience to recognize the creatures from poems predating his epic. On hearing of the Sirens, Homer’s listeners might automatically have pictured the birds with female heads familiar to us from their depictions on vases. But how the Sirens originally took this form is uncertain. Their rendering as fully aquatic creatures and their melding with the mermaids is just another case of pin-the-fish-tail-on-the-maiden. Perry notes that the roots of the word siren may be linked to the Greek term for a rope used for drawing, or to a word suggesting “heat”—an “alluring, but wasting and putrefying heat.” This latter etymology fits with the interpretation of the Sirens as “demons of sloth and corruption.” (Horace labeled “idleness” itself a Siren.) Their nature, Perry opines, mirrored the “sultry, sickly heat, such as many of us may have felt in the Bay of Naples, the home of the Sirens.” The Sirens represent the tranquil sea that hides the “jagged rock and engulfing quicksand”; hence the poet Claudian’s oxymoronic reference to them as “pleasing terrors.” The oldest myths concerning their birth tie them to the preeminent river god Achelous and a fight he got into with Hercules over the beautiful Deianeira. To escape Hercules’ wrath, Achelous transformed himself into a bull. In the fury of battle, Hercules ripped off one of the bull’s horns, and the Sirens emerged from the blood gushing out of this wound. From their inception, the Sirens were associated with violence, yet they did not themselves administer the coup de grâce; they were violence mediated, atrocity once removed.

Transporting the listener beyond the self with their sound, the Sirens maintain a twisted copycat relationship with the Muses through the annals of classic literature. Like the Sirens, the Muses were associated with birds—though they did not themselves take avian form—and they are, of course, most revered for their enchanting music. Those privileged to hear the Muses’ song are infused with cosmic knowledge that enables creation. Though rarely remarked upon, ever since Homer the lure of the Sirens has actually been twofold: their sweet sound and the Orphic content of their song. “We know all the pains that the Greeks and Trojans once endured…” they chant to Odysseus on his mast, “all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all!” The Sirens present themselves to Odysseus as a comprehensive archive of past human suffering, and a Cassandra-style vision feed of all disasters yet to come. Their song bears so much knowledge that it can inspire only cosmic melancholy.

This omniscience of the Sirens may be the reason some sources record that they ran a renowned academy at a place called Massa. In Pope’s translation of The Odyssey, he notes that the academy was “famous for eloquence and liberal sciences.” Why, then, were the Sirens “fabled to be destroyers”? Students of the Sirens, Pope explains, “abused their knowledge, to the colouring of wrong, the corruption of manners and the subversion of government.” In a paradox we in the Internet age can relate to, the Sirens’ open-source-style, maxi-access willingness to supply knowledge of everything to visitors at their charming site overwhelmed human capacity to actually do anything with what was gleaned there. While loitering in the Sirens’ web, Pope asserts, pupils “consumed their patrimonies, and poisoned their virtues with riot and effeminacy.”[9]

Contrasting the elevating effects of the Olympian Muses’ song with the downer-drowner tunes of the Sirens, Perry labels the Sirens “Muses of Hades.” At least since the fifth century, the Sirens have been linked to the underworld in plays, philosophical discourse, and carvings on funerary monuments. Yet the distinction between higher and lower otherworldly realms can become murky, since the underworld is humanity’s common destiny—and sometimes represents a noble aspiration. Plato entirely confused the two sets of muses and projected the sirens into orbit, where they helped produce the harmony of the spheres. Over time, the Sirens also began to be muddled up with the Harpies. Indeed, the question of what humanity was really supposed to make of the Sirens’ chthonic melodies entangles writers and artists through the ages. Hesiod called Homer himself a Siren. Pausanias declared that at the death of Sophocles, Dionysius commanded the Athenians to worship him “as a new Siren.” Whatever else, the power of the Sirens’ song lay not in snappy vivacity, but in its mingling of sweetness and sadness, the mixing of memory and desire. (Think of a sound resembling fado, only higher pitched. Fado sung by Kate Bush.) This is one reason Euripides has Helen call these “winged maidens, virgin daughters of the earth” to come to her in her subterranean grief, bringing with them the Libyan flute and pan-pipes, in order to make “paeans to the departed dead.” Sirens became symbolically associated with the dirge, and one of their main functions was to serve as “wailers” in funereal art. In this capacity, the Sirens, often holding musical instruments, were probably benevolent. Their wailing consoled the anguished mourner.[10]

And here, we begin our return to the problem of our own wailing siren technology. Critics of the Sirens spotlight their role as distracters from purposeful activity. The Sirens unravel our worldly ambitions by mesmerizing us with music that sucks us down into the depths of a seductive melancholy—the kind of mood indigo that Robert Burton refers to in the introductory poem to his opus when he writes, “All my joys to this are folly, / Naught so sweet as melancholy.” Poets and philosophers founder on the question of whether the misery of the human condition might not demand the kind of engulfing aesthetic experience proffered by the Sirens as a remedy for the pain of existence. Sometimes the saddest song is the most effective vaccination against despair. DC police chief Lanier argued that new technology, by proffering an endless supply of “something to distract folks,” made people oblivious to their surroundings. True enough. But dominated by traffic noise, infrastructure roars, crashes and shrieks, along with countless auditory come-ons from commercial interests, our public spaces have devolved into ghastly sonic dumping grounds. It’s often only in the individualized sound bubble that we can escape from the distractions of the auditory wasteland we’ve been condemned to and find solace for the fact that we already inhabit a Noise Underworld. “The Rumbler,” remarked Lanier, “helps shake that distraction” endemic to the age of technology. She did not add that it does so by creating a distraction more disruptive of interior life than any vehicular sound before it. (Though once we learn to protect ourselves against that noise by blocking it with some yet noisier private sound sealant, the Rumbler will no doubt be superseded by a still more piercing siren: the Disembowler, perhaps.) Schopenhauer declared that the superiority of a great intellect depends entirely on the capacity to concentrate; its strength vanishes instantly when diffracted by disturbance. “Noise is the most impertinent of all forms of interruption,” he declared.[11]

Researchers have observed that all our stress markers elevate on hearing a siren, even when we consciously pay no attention to it. Our physiologies never learn that every siren we hear isn’t coming to get us. Whether resembling ghoul cat cries, mad birds, or blurts from rhinos on steroids, sirens have been designed to convey one fact above all: these beasts are not on our side. Striking somewhere full fathom five in the amygdala, sirens conjure the nightmare predators our ancestors froze before or flew from on peril of their lives.

At current sound levels, the child’s fantasy has come true: the siren itself has become the monster to fear.

In the beginning, sirens made music. John Robison—a moon-faced eighteenth-century physicist and mathematician who collaborated with James Watt on an early steam car and was a prominent member of the Edinburgh Philosophical Society who became, in later life, an obsessive conspiracy theorist—wanted to measure the number of air pulses that went into producing a given pitch. A few years after completing his paranoiac masterwork, “Proofs of a Conspiracy against all the Religions and Governments of Europe, Carried on in the Secret Meetings of Freemasons, Illuminati and Reading Societies,” Robison constructed a stopcock that could rapidly open and shut the passage of a pipe. He then attached this apparatus to the pipe of a conduit leading from the bellows to the wind-chest of an organ. Opening the cock allowed air to flow along the pipe into the organ. In addition to discovering the invention’s pitch-gauging capacities, he found that by varying the speed at which the cock opened and shut he could create different sounds. At 720 times a second, Robison declared, the “smoothly uttered” sound was “equal in sweetness to a clear female voice.”[12] Twenty years later, Cagniard de la Tour refined Robison’s device so that it now comprised two discs, each pierced by one hundred oblique apertures and mounted on a pneumatic tube. The lower disc was stationary, while the upper one could spin. When air was forced through the holes of the bottom plate, the upper one revolved. Sometimes the two sets of holes aligned, allowing a puff of air to pass through, sometimes they did not; the succession of air puffs produced a musical note. De la Tour called the instrument a “siren” because it was equally capable of making its music when water passed through it rather than air, or when the whole instrument was submerged. Listeners marveled not only at its pleasing harmonics, but also at how loud the siren could be.[13]

It wasn’t until the late 1860s that Professor Joseph Henry, a dominant presence on the United States Light-house Board, began fiddling with de la Tour’s instrument to develop a steam-powered siren for use as a fog signal. Henry’s device worked by driving steam through slits in two disks: one fixed, one mobile. However, Henry’s mobile disk was placed in the throat of a large trumpet. At sufficient pressure, steam made the mobile disk spin 2400 times a minute, producing 480 vibrations per second and creating a sound that could be heard up to thirty miles away. For the first time, the siren moved from being a source of beguiling song to serving as an engine of alarm. Indeed, a series of tests in the mid-1870s comparing sirens to guns, horns, and whistles determined that sirens traveled further in space and penetrated more local noises than any other acoustical signal.[14]

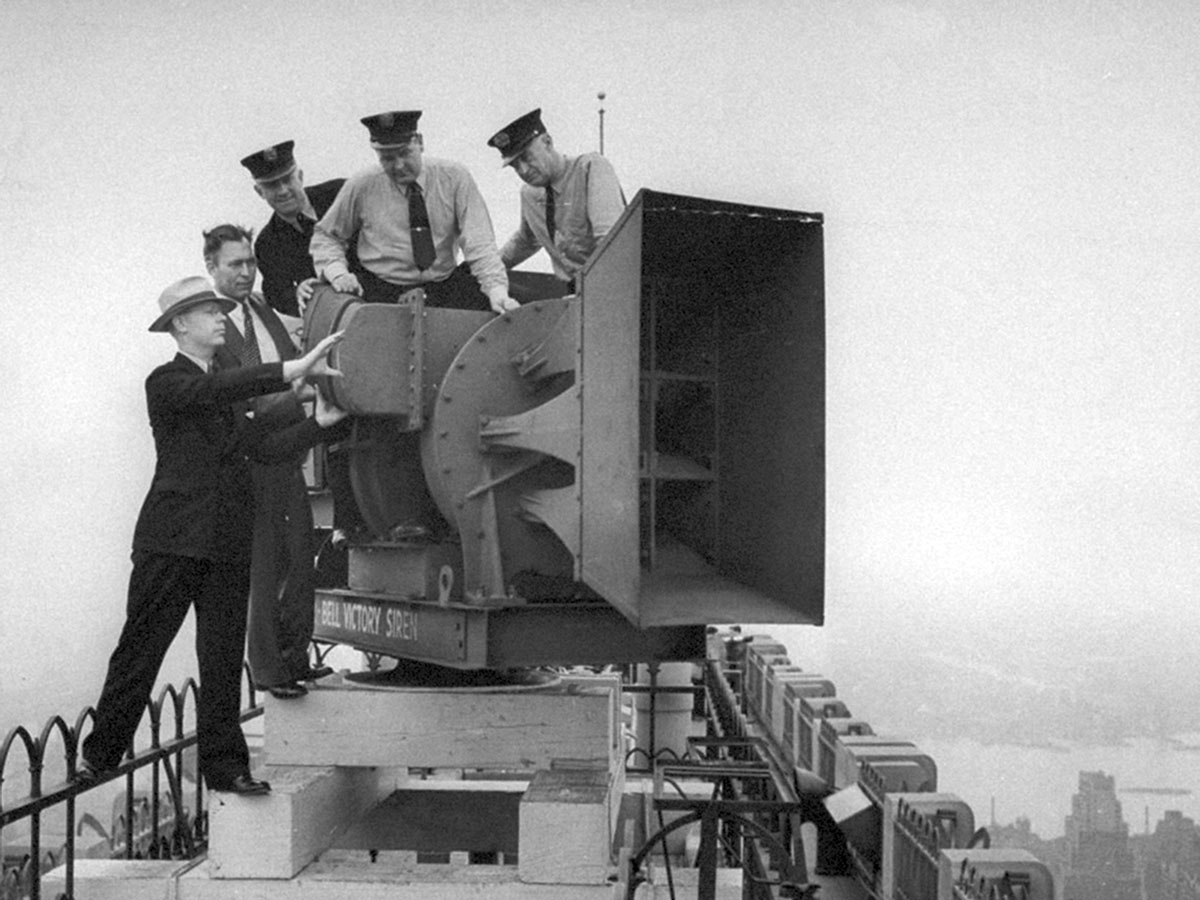

As the siren’s supreme audibility gained recognition, it became the favored device for alerts of every variety. This popularity drove innovations in siren technology: sirens went mechanical, electromechanical, and ultimately purely electrical. Crank-operated sirens started being introduced into fire stations and fixed to mobile fire equipment (often on top of existing warning bells) around 1913. In 1924, the New York Fire Commissioner began installing sirens at congested intersections throughout the city, noting that there was currently more danger in traveling to a fire than in putting one out.[15] The aerial bombing campaigns of World War I inspired the creation of air raid sirens. By war’s end, many European and American cities alike had installed systems that could be heard for miles, and siren potency became a new point of metropolitan pride. (Purportedly the loudest civil defense siren ever made was produced during the Cold War. The Chrysler Siren employed six air horns fed by an air compressor running on an 180-horsepower V-8 engine. It was said to be so powerful that it could start fires with sound vibrations and turn fog into rain.)[16] A deficit of air attacks on the continental United States prompted city planners to devise new functions for sirens, some exceptional—like warning authorities of incipient riots—others everyday, like marking the hour. In factories around the world, sirens began replacing the traditional steam whistle summoning and releasing workers.

Because of their association with dynamic production and revolutionary violence, sirens became an emblem of modernity—which in turn led to their being folded back into the arsenal of artists. In 1922, the Soviet film director Sergei Yutkevich declared, “The electric siren of Contemporaneity bursts with a mighty roar into the perfumed boudoirs of artistic aestheticism!” In 1927, George Antheil scored a fire siren into the climax of his Ballet Mécanique. (At its New York premiere, the siren operator, having forgotten that a minute of cranking was needed to make a sound, left the cranking until too late so that the performance ended in total silence; only as the audience began to applaud and depart did the shrieking commence.)[17] In a world rife with things to be alarmed about, sirens began to be introduced into more and more places. During the 1920s, shop owners started placing electric sirens around stores. A Chicago businessmen’s association armed merchants with “sawed-off shot guns of the repeater type,” promising the press that “when the siren calls they will answer.”[18] A siren-handbag was invented in 1931 for use by bank messengers and to foil “snatchers.” A small metal lever placed under the handle of the bags was gripped by the carrier; when attacked, carriers were to release their grip, whereupon the lever fell, setting off a shrill siren that would blow for three hours.[19] The new proliferation in sirens could itself create alarm, however. In 1919, a stuck throttle on a whistle at a railroad roadhouse in Indianapolis triggered a chain reaction whereby almost every siren in the city started wailing. City residents rushed to church believing that the end of the world had arrived.[20]

It was in the early 1970s that police and fire officials started complaining of a spike in accidents caused by drivers not hearing sirens. The phenomenon derived, as one New York Times article observed, from better automotive soundproofing and greater noise levels outside cars, along with “higher noise levels inside autos—from stereo radios and tape players and air conditioners.” Consequently, sirens could no longer be heard by drivers, until emergency vehicles were so close as to render the alert useless. The challenge, according to one professor of audiology, was how to create a siren that emitted sound which “fit the human ear...[and] can be heard by ears with hearing losses and over competing messages and by those drivers who don’t want to cooperate.” He added that when noisier sirens become commonplace they no longer command attention.[21] Moreover, at sufficiently loud levels, sirens damaged the hearing of emergency-vehicle drivers and could trigger heart attacks in patients. An extensive US Department of Transportation study undertaken in 1978 to grapple with these problems concluded that sirens would never become an effective warning device.[22] Siren manufacturers responded to the predicament by simply producing louder sirens. “The demand is obviously there,” declared a Federal Signal spokesperson.

What is to be done? Against a state of endless, ever-amplifying sonic alarm, we might recall Kafka’s dictum: “Now the Sirens have a still more fatal weapon than their song, namely their silence.”[23]

- “N.Y.P.D. Sirens,” The New York Times, 14 June 2007, and Cara Buckley, “An Earsplitting Symphony, With the Maestro in Blue,” The New York Times, 15 June 2007.

- Joe Bader, vice-president of engineering for Federal Signal, interview with author, January 2011. See also www.fedsig.com/products/253/rumbler (accessed 31 March 2011). On the class action suits filed against Federal Signal, see, for example, bagoliefriedman.com/fire_fighter_hearing_loss.shtml [link defunct—Eds.] (accessed 31 March 2011) and Amitai Etzioni, “Shame Them: What to do With Corrupt Experts,” www.dailykos.com/story/2007/06/27/351175/-Shame-Them;-What-to-do-With-Corrupt-Experts (accessed 31 March 2011).

- Oren Dorell, “New Booming Police Siren Rattling Nerves,” USA Today, 7 February 2008.

- “N.Y.P.D. to Shake Things Up With the Rumbler Super Siren,” wheels.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/26/nypd-to-shakes-things-up-with-the-rumbler-super-siren (accessed 31 March 2011).

- See, for example, Michael Harley, “Tulsa Police Testing Booty-Shaking Rumbler Sirens,” autoblog.com/2008/02/22/tulsa-police-testing-booty-shaking-rumbler-sirens (accessed 31 March 2011).

- Richard S. Chang, “More than 7,500 Drivers Cited for Cellphone Use,” wheels.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/10/27/7500-drivers-cited-for-cellphone-use (accessed 31 March 2011).

- Walter Copland Perry, “The Sirens in Ancient Literature and Art,” The Nineteenth Century, vol. 14 (July 1883), pp. 109–130.

- Homer, The Odyssey, trans. Robert Fagles (New York: Penguin Book, 1996), pp. 272–277.

- Thomas Busby, A General History of Music (London: G. and W. B. Whittaker, and Simpkin and Marshall, 1819), pp. 115–116.

- In addition to Perry, see, for example, Catherine Draycott, “Bird-women on the Harpy Monument from Xanthos, Lycia: Sirens or Harpies?” in Donna Kurtz with Caspar Meyer, David Saunders, Athena Tsingarida and Nicole Harris (eds.), Essays in Classical Archaeology for Eleni Hatzivassiliou, 1977–2007 (Oxford: Archaeopress, 2008) pp. 145–153, and Cecil Smith, “Harpies in Greek Art,” Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 13, (1892–1893), pp. 103–104.

- Arthur Schopenhauer, Complete Essays of Schopenhauer: Seven Books in One Volume, trans. T. Bailey Saunders (New York: Willey Book Company, 1942), Book V (Studies in Pessimism), pp. 90–95.

- John Tyndall, Sound: A Course of Eight Lectures Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1867), p. 55.

- See, for example, John Broadhouse, Musical Acoustics or The Phenomenon of Sound as Connected With Music (London: William Reeves, 1881), p. 98, and Alfred Payson Gage, The Principles of Physics (Boston: Ginn & Company, 1907), pp. 178–179.

- Edward P. Adams, “The Light-House System of the United States,” Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies, vol. 12 (January 1893–December 1893), p. 530, and Thomas Henry Huxley, “Recent Science,” The Nineteenth Century, vol. 3 (January–June 1878), pp. 1140–1142.

- “New Fire Siren Is Tested,” The New York Times, 29 April 1924.

- See David Stall, “Presenting the Historic Chrysler Siren,” www.victorysiren.com/x/index.htm [link defunct—Eds.].

- Douglas Kahn, Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1999). Yutkevich cited on p. 84; George Antheil anecdote on p. 124.

- “Sirens as Robber Alarms,” The New York Times, 1 January 1920.

- “Handbag with a Siren to Scare Thieves,” The New York Times, 22 March 1936.

- “Whistles Startle a City,” The New York Times, 18 December 1919.

- “Sirens Unheard in Closed Cars Are Growing Problem in Cities,” The New York Times, 29 April 1973.

- Robert A. De Lorenzo & Mark A. Eilers, “Lights and Sirens: A Review of Emergency Vehicle Warning Systems,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, vol. 20, no. 12 (December 1991), pp. 1331–1335.

- Franz Kafka cited in George Steiner, Language and Silence: Essays on Language, Literature and the Inhuman (New York: Atheneum, 1967), p. 54.

George Prochnik is a New York–based writer. His most recent book is In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise (Doubleday, 2010). Currently, he is at work on two books—one about early twentieth-century case histories involving madness, murder, freaks, and elephants; the other about objectless pilgrimage.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.