Our Aesthetic Categories: An Interview with Sianne Ngai

The cute, the interesting, and the zany

Adam Jasper and Sianne Ngai

Aesthetics as a philosophical discipline was an invention of the Enlightenment, and appropriately enough, most of the historical discussion has focused on the beautiful and the sublime. However, as J. L. Austin noted in “A Plea for Excuses,” the classic problems are not always the best site for fieldwork in aesthetics: “If only we could forget for a while about the beautiful and get down instead to the dainty and the dumpy.”

Sianne Ngai, a professor in the English department at Stanford University, has dedicated years of research to such marginal categories within aesthetics. She is the author of a book on minor affects called Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2005) and several heavily photocopied papers on aesthetics, including “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde” (2005) and “Merely Interesting” (2008). Her forthcoming book expands her investigation of apparently trivial but culturally ubiquitous aesthetic categories to include the zany. Adam Jasper interviewed Ngai by email.

Cabinet: You’ve written on cuteness, on envy, on boredom, and now on the interesting. If it could be said that there is a unified project behind these topics, what is it?

Sianne Ngai: I’m interested in states of weakness: in “minor” or non-cathartic feelings that index situations of suspended agency; in trivial aesthetic categories grounded in ambivalent or even explicitly contradictory feelings. More specifically, I’m interested in the surprising power these weak affects and aesthetic categories seem to have, in why they’ve become so paradoxically central to late capitalist culture. The book I’m currently completing is on the contemporary significance of three aesthetic categories in particular: the cute, the interesting, and the zany.

I focus on aesthetic experiences grounded in equivocal affects. In fact, the aesthetic categories that interest me most are ones grounded on feelings that explicitly clash. To call something cute, in vivid contrast to, say, beautiful, or disgusting, is to leave it ambiguous whether one even regards it positively or negatively. Yet who would deny that cuteness is an aesthetic, if not the dominant aesthetic of consumer society?

Can you say more about the qualities of non-cathartic feelings? The explicit rejection of catharsis was central to Brechtian theater, but is that what you are referring to here?By non-cathartic I just mean feelings that do not facilitate action, that do not lead to or culminate in some kind of purgation or release—irritation, for example, as opposed to anger. These feelings are therefore politically ambiguous, but good for diagnosing states of suspended agency, due in part to their diffusiveness and/or lack of definite objects.

To get our hands a little dirtier here, could you provide some examples of typically cute and typically zany things and indicate the characteristics that make them that way?Cuteness is a way of aestheticizing powerlessness. It hinges on a sentimental attitude toward the diminutive and/or weak, which is why cute objects—formally simple or noncomplex, and deeply associated with the infantile, the feminine, and the unthreatening—get even cuter when perceived as injured or disabled. So there’s a sadistic side to this tender emotion, as people like Daniel Harris have noted. The prototypically cute object is the child’s toy or stuffed animal.

Cuteness is also a commodity aesthetic, with close ties to the pleasures of domesticity and easy consumption. As Walter Benjamin put it: “If the soul of the commodity which Marx occasionally mentions in jest existed, it would be the most empathetic ever encountered in the realm of souls, for it would have to see in everyone the buyer in whose hand and house it wants to nestle.” Cuteness could also be thought of as a kind of pastoral or romance, in that it indexes the paradoxical complexity of our desire for a simpler relation to our commodities, one that tries in a utopian fashion to recover their qualitative dimension as use.

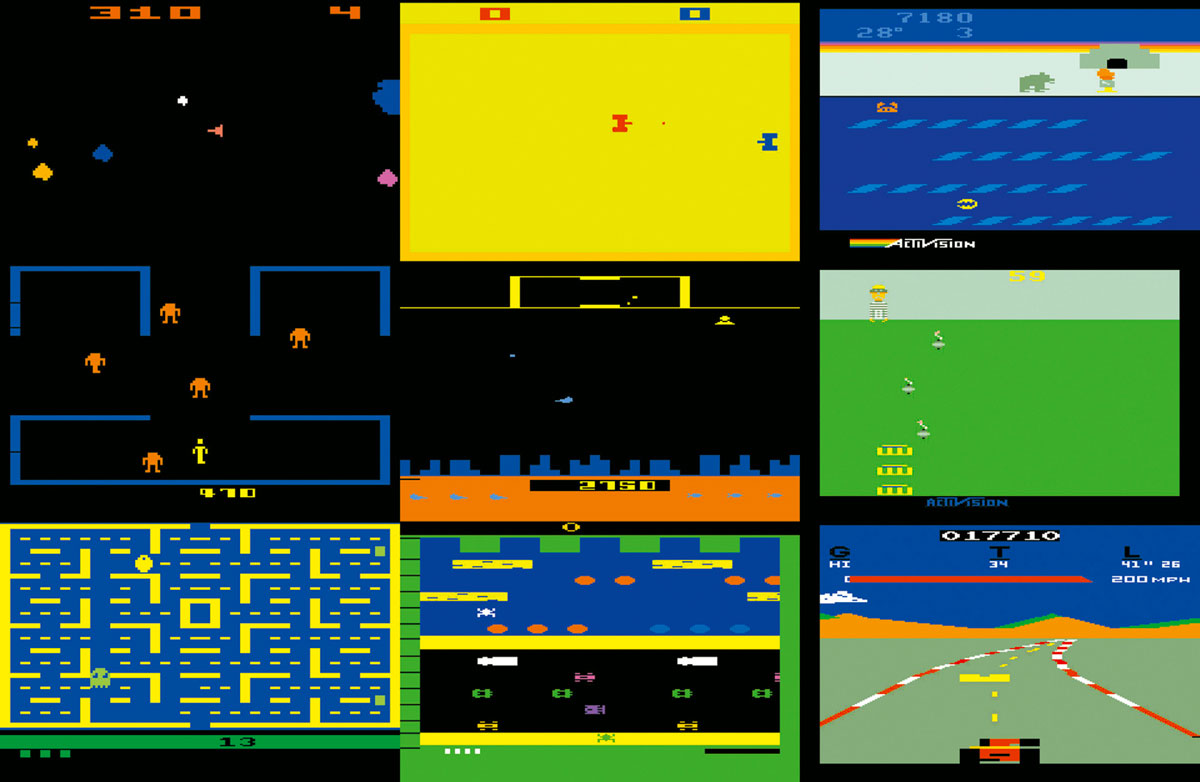

While the cute is thus about commodities and consumption, the zany is about performing. Intensely affective and highly physical, it’s an aesthetic of nonstop action that bridges popular and avant-garde practice across a wide range of media: from the Dada cabaret of Hugo Ball to the sitcom of Lucille Ball. You could say that zaniness is essentially the experience of an agent confronted by—even endangered by—too many things coming at her quickly and at once. Think here of Frogger, Kaboom!, or Pressure Cooker, early Atari 2600 video games in which avatars have to dodge oncoming cars, catch falling bombs, and meet incoming hamburger orders at increasing speeds. Or virtually any Thomas Pynchon novel, bombarding protagonist and reader with hundreds of informational bits which may or may not add up to a conspiracy.

The dynamics of this aesthetic of incessant doing are thus perhaps best studied in the arts of live and recorded performance—dance, happenings, walkabouts, reenactments, game shows, video games. Yet zaniness is by no means exclusive to the performing arts. So much of “serious” postwar American literature is zany, for instance, that one reviewer’s description of Donald Barthelme’s Snow White—“a staccato burst of verbal star shells, pinwheel phrases, [and] cherry bombs of … puns and wordplays”—seems applicable to the bulk of the post-1945 canon, from Ashbery to Flarf; Ishmael Reed to Shelley Jackson.

I’ve got a more specific reading of post-Fordist or contemporary zaniness, which is that it is an aesthetic explicitly about the politically ambiguous convergence of cultural and occupational performance, or playing and laboring, under what Luc Boltanski and Eve Chiapello call the new “connexionist” spirit of capitalism. As perhaps exemplified best by the maniacal frivolity of the characters played by Ball in I Love Lucy, Richard Pryor in The Toy, and Jim Carrey in The Cable Guy, the zany more specifically evokes the performance of affective labor—the production of affects and relationships—as it comes to increasingly trouble the very distinction between work and play. This explains why this ludic aesthetic has a noticeably unfun or stressed-out layer to it. Contemporary zaniness is not just an aesthetic about play but about work, and also about precarity, which is why the threat of injury is always hovering about it.

What is the underlying connection between affects and aesthetic experience?

I think Gerard Genette is right to say that all of our aesthetic predicates are “objectifications” of feeling. To make an aesthetic judgment, with all its necessary claims for universality, is to project one’s feelings onto the object in such a totalizing fashion that the “actually subjective” basis of the judgment of aesthetic quality ends up being somewhat incidental to how we experience or understand that quality.

Does this mean there is a one-to-one correspondence between the minor affects and marginal aesthetic categories?No. The former are sort of like raw materials for the latter, which are both descriptive and evaluative. In fact, and this is part of what intrigues me about them, aesthetic judgments like the ones in my study revolve around multiple and even conflicting feelings: tenderness and aggression, in the case of the cute; fun and unfun, in the case of the zany; interest and boredom, in the case of the interesting. I should stress that these aesthetic categories are trivial, but not for all that marginal. In fact, my argument is that they are absolutely central not just to postmodern culture, but for a proper understanding of how the very concept of the “aesthetic” has been perhaps irreversibly changed under the hypercommodified, intensively informated and networked, performance-driven conditions of late capitalism.

The centrality of judgment to aesthetic experience remains controversial. For Kant, Clement Greenberg, and others, it seems like there can be no such thing as an aesthetic experience without judgment, while Nietzsche and others suggest the contrary. I think the former camp is ultimately right on this, which is why I treat aesthetic categories as both discursive evaluations (“cute” as something we say, a very particular way of communicating a very particular kind of pleasure) and as objective styles (cuteness as a commodity aesthetic, as a sensuous/formal quality of objects), and try to pay close attention to the relation between them. At the same time, I don’t agree that aesthetic experience/judgment is necessarily synonymous with conviction. Or reverence, or idealization.

Contemporary theorists continue to attribute the specificity of aesthetic experience to the presence of a special, singular emotion like “disinterestedness.” Yet most of our aesthetic experiences are based on combinations of ordinary feelings. Aesthetic judgments based on clashing feelings, in particular, mirror the disputes between subjects or groups that underlie them: a state of social conflict that not all aesthetic categories make equally transparent.

I’m drawn to these weak or equivocal aesthetic categories because, precisely in not being experiences of conviction, they foreground the question of their justification outright. Indeed, judgments like “interesting” seem to demand justification, much in the same way that all aesthetic judgments (including even “interesting”) demand concurrence. The justification of aesthetic judgments, which will always involve an appeal to extra-aesthetic judgments—political, moral, historical, cognitive, and so on—is, I think, the really interesting heart of all aesthetic discourse and experience. Aesthetics is a discourse not just of pleasure and evaluation, but of justification. How we talk about pleasure and displeasure turns out to be a very rhetorically tricky and socially complicated thing.

How can you subscribe to Kant’s theory of aesthetic judgments as making a claim for universality, but at the same time argue that these judgments are not necessarily ones of conviction? Isn’t that a contradiction?Not necessarily. Cute, interesting, and zany are based on the complex feelings that arise from our encounters with notably “formless” forms: the squishy blob, the indefinite series, the chaotic flow of activity. Yet all make the claim to universal validity that every aesthetic judgment makes and in the same distinctively performative mode—if perhaps not with the same degree of affective force as our judgments of, say, the beautiful or disgusting.

When I judge something to be cute, or even interesting, I’m judging it to be objectively so. I’m compelled to say that “interesting” is a quality of the object, precisely because putting it this way is the most forceful way, the best way to get others to agree with me. That’s the claim for universality, without which a judgment would not be a judgment of taste. Having had to put the judgment in this objective format, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that its axiological charge is going to be unequivocally positive or negative. Or that the affective force of the judgment is going to be strong.

Cute is a good example. I’m compelled to speak of it as an objective property of an object, which reflects my demand that everyone judge that object the same way. But our experience of something or somebody as cute is itself easily overpowered by a second feeling of manipulation or exploitation. Like the sentimental, which as literary critic Jennifer Fleissner points out, we wouldn’t call “sentimental” if it really moved us deeply in the way that it aims to, the cute seems coupled with a certain inability to complete its own project. The same could also be said of the zany, tellingly defined by one online dictionary as a “ludicrous” character (that is, one who is not really convincing) who “attempts feebly” (that is, badly) to “mimic the tricks of the clown.” And the same could also be said of the interesting, always just a step away from being merely interesting and thus just a step away from being boring. In comparison to powerful experiences like that of the sublime or disgusting, these aesthetic experiences are profoundly equivocal; indeed, they almost seem to call attention to their relative lack of aesthetic impact or power, to their own aesthetic ineffectuality. But that doesn’t finally negate their status as aesthetic categories. And to me it makes them all the more worthy of our intellectual attention.

During a conversation about this project, Ken Reinhard jokingly pointed out how these three aesthetic experiences can easily turn pathological, in a way that almost perfectly corresponds to Freud’s categories of neurosis: phobia, in the case of cute (because cute objects can quickly become gross or disgusting); hysteria, in the case of zaniness; obsession, in the case of the interesting. I think I’m attracted to them for this reason as well, though I didn’t realize this until he pointed it out!

Could you explain a little more how the aesthetic categories that interest you acquire the capacity to reveal social conflicts? I’m not being willfully ignorant. My bias can be read back to Frank Sibley, who wrote about the way in which aesthetic justifications ultimately resolve, at least in written description, in non-aesthetic terms. However he also insisted upon the irreplaceable role of direct personal experience of the aesthetic object. No one can convince you of the beauty, elegance, or garishness of an object by describing it.The act of professing aesthetic pleasure or displeasure, in and of itself, is not interesting to me. What is interesting is the complexity of the ways in which people then defend these judgments (which they feel just as strongly compelled to do). As Simon Frith aptly puts it, “Value judgments only make sense as part of an argument and arguments are always social events.” So in my comment above, I just was thinking in a general way about what John Guillory calls the “constitutive role of conflict for any discourse of value.” That said, the argument of my second book is that the commodity aesthetic of the cute, the performance-oriented aesthetic of the zany, and the informational and discursive aesthetic of the interesting have a unique and even indexical relation to the ways in which the subjects of late capitalism consume, labor, and exchange. Insofar as these socially binding processes are also, inevitably, sites and stakes of social struggle, the aesthetic categories featured in the book reflect these struggles, albeit in a highly indirect and mediated fashion.

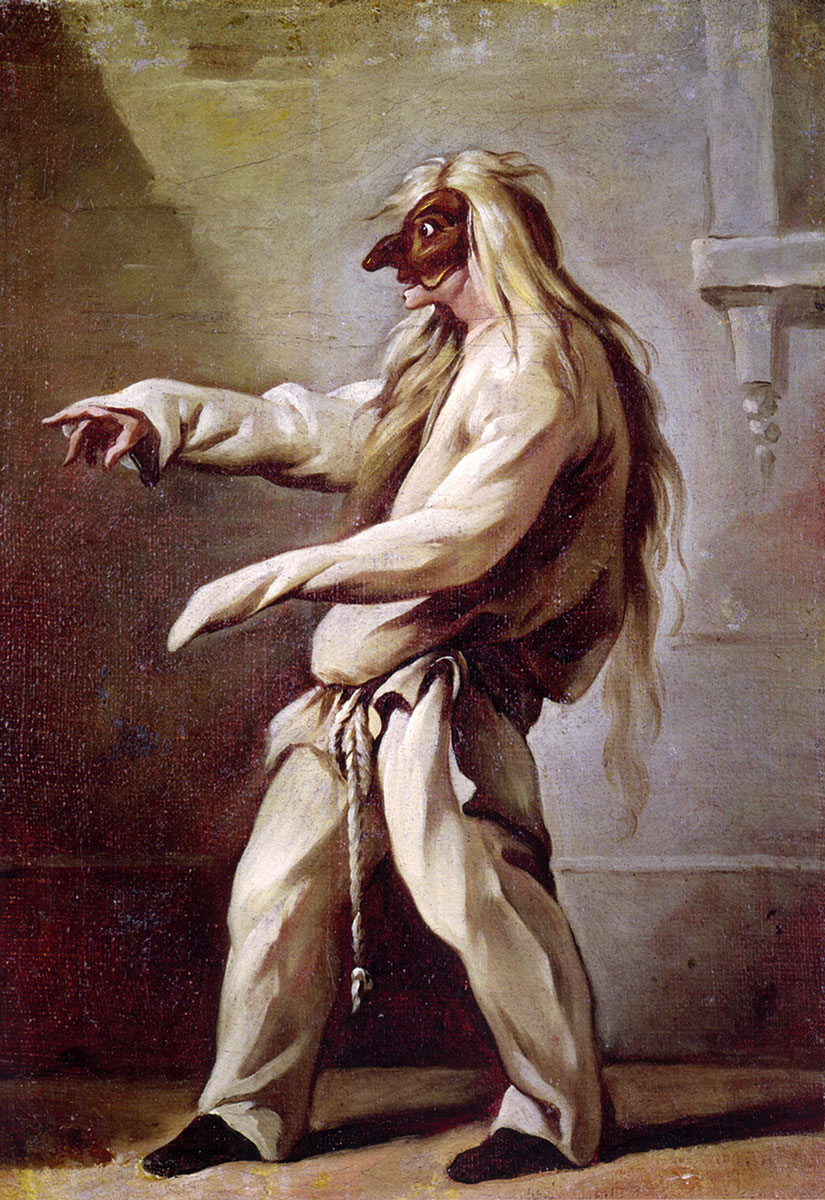

The zany, for example, is an aesthetic not just about cultural performance but about performance as affective labor, whose gendered status in the post-Fordist culture of what Heather Hicks calls “soft work” becomes increasingly ambiguous. And in a way that repositions gender, in a historically unprecedented way, as a central question for late-capitalist zaniness, as we see in I Love Lucy. The longstanding question of the relation between gender and class gets raised by the question of how post-Fordist zaniness differs from its precedents. It’s worth noting here that zaniness is an old but distinctively modern style of performing in which the employer/employee or master/servant agon has always played a central role, since its inception with the character of the Zanni (an itinerant servant) in sixteenth-century commedia dell’arte. It’s only in the late twentieth century that the question of gender starts to become increasingly central to this aesthetic about work.

The asymmetry of power that cuteness revolves around is another compelling reminder of how aesthetic categories register social conflict. There can be no experience of any person or object as cute that does not somehow call up the subject’s sense of power over those who are less powerful. But, as Lori Merish underscores, the fact that the cute object seems capable of making an affective demand on the subject—a demand for care that the subject is culturally as well as biologically compelled to fulfill—is already a sign that “cute” does not just denote a static power differential, but rather a dynamic and complex power struggle.

Finally, the very idea of “interest” underlying the interesting points to the aesthetic judgment’s unique role in facilitating “precise comparisons and contrasts between individuals or groups” and thus in negotiating disputes between them. As Jan Mieszkowsi notes, “interests never exist as unique, autonomous impulses, but only in and as their collisions with other interests.” The fact that “before it can be considered as a preference or aim, an interest must be understood as a contradiction with other interests” means “any interest—or a person, a tribe or a state—is [already] a counter-interest.”

As a judgment, “interesting” is often applied to art objects and in your essay “Merely Interesting,” you treat it as a category of aesthetic experience when it is used in this way. In what ways does “interesting” conform to, and differ from, the traditional aesthetic categories such as the beautiful and the sublime?When I first started working on the interesting I followed Schlegel in regarding it as the antithesis of the beautiful. But then I started to realize that it illuminated or brought forth aspects of Kant’s privileged example of aesthetic judgment in an even more perspicuous way than beauty! This is the case even though the interesting isn’t an exclusively aesthetic category. In fact, it’s a term critics often deliberately use to toggle between aesthetic and extra-aesthetic judgments.

But let me first say something about the Kantian sublime. Could an aesthetic category like interesting, an affectively low-key response to minor differences perceived against a background of sameness, have anything in common with such a powerful response to sheer power? (Not form, as Lyotard underscores, but rather pure quantity or magnitude.) There is one surprising point of similarity: the sublime is still western philosophy’s most prestigious example of an aesthetic category that derives its specificity from mixed or conflicting feelings. Yet unlike the mix of interest and boredom in the interesting, or aggression and tenderness in the cute, in the sublime these contradictory feelings are not held in indefinite tension. What makes the sublime “sublime” is precisely the fact of its emphatic resolution; that the initial feeling of discord culminates in the feeling Kant calls “respect.” This final feeling is singular and unequivocal. And it is always intense.

The relationship between the interesting and the beautiful is much closer. With its cool affect and relatively weak cathexis with its objects, the interesting arguably resembles the “disinterested pleasure” of beauty more than it differs from it! More significantly, the interesting’s lack of descriptive specificity mirrors the conceptlessness of the reflective judgment of beauty as conceived by Kant. I’ve always found this fact particularly striking. The difference is that the blankness or indeterminacy of the judgment of interesting seems to explicitly invite us to fill in the blank with the concept later. The interesting is an explicitly epistemological aesthetic, in a way that the beautiful is not. Finally, the discursivity of the interesting makes plain the dialogism and matrix of social conflict underlying all judgments of taste.

Can you elaborate on what you mean by the interesting’s “discursivity,” and how that connects to or helps bring out something about beauty?

Think of the ubiquity of the weak judgment in everyday conversation, and how it gets used to implicitly invite others to demand, in turn, that the person who has just proclaimed something interesting take the next step of explaining why. Also, consider this quotation from Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, dominated by dialogue as the “novel of ideas” always tends to be: “If one was fundamentally interested in a thing, when one talked about it one could hardly help drawing others in, infecting them with it, and so creating an interest up to then not present or dreamed of. And that was worth a great deal more than catering to one already existent.” This moment from Mann’s novel, famously based on Adorno’s theoretical writings on music, is striking for several reasons. First, it underscores the performativity of the interesting. Judging something interesting is often a first step in actually making it so. Which is why there is an explicitly pedagogical dimension to the interesting. (Not accidentally, the speaker of the quotation is a piano teacher). Second, it highlights how our experience of something as interesting compels us to immediately talk about it. As if there could be no aesthetic experience of the interesting without the talk.

For Kant, similarly, it does not seem possible to judge something beautiful without speaking, or at the very least, imagining oneself speaking. Some may think I am overreading certain early moments in the third Critique in making this claim (sections 6 and 7), but I do think the compulsion to literally speak, the compulsion to make one’s pleasure public, is fundamental to aesthetic judgment (and therefore, one might argue, to aesthetic experience). Though he doesn’t put it as crudely as I just did, Stanley Cavell’s reading of the Kantian aesthetic judgment as a perlocutionary speech act suggests so as well. I also think Derrida has this in mind when, in the Truth in Painting, he refers to the “discursivity in the structure of the beautiful.” Indeed, for Kant, what one judges in the pure judgment of taste is less the object or even the feeling of pleasure that follows its judging, but rather the communicability of that feeling. And, as Hannah Arendt argues, for Kant communicability quite explicitly means “speech.”

Explicitly asking us to link our aesthetic judgments to extra-aesthetic ones (in the act of justification), the evaluation of interesting tends, if nothing else, to prolong critical conversations.

Could you tell us more about what Schlegel had to say about the interesting? Is there an overlap between the interesting and the ironic?In a 1797 essay called “On the Origins of Greek Poetry,” Schlegel explicitly sets the interesting, which he associates with the literature of modernity, in direct opposition to the beautiful poetry of the Greeks. While die schöne Poesie is objectively rule-bound, universal, and disinterested, die interessante Poesie is subjective and idiosyncratic, open to interminable particularization because no laws govern its determination by any content in particular. So here is the historical link between the maker of interesting art and the figure of the romantic ironist: both are defined by the lack of attachment to any particular worldview, and thus by an ability to “take on any subject-matter or artistic style” (as Hegel put it, negatively—he was not a fan of irony, nor of the Schlegels). In a way that may come as a surprise to many, the aesthetic of the interesting thus has a fairly lofty pedigree in high theory and literary criticism.

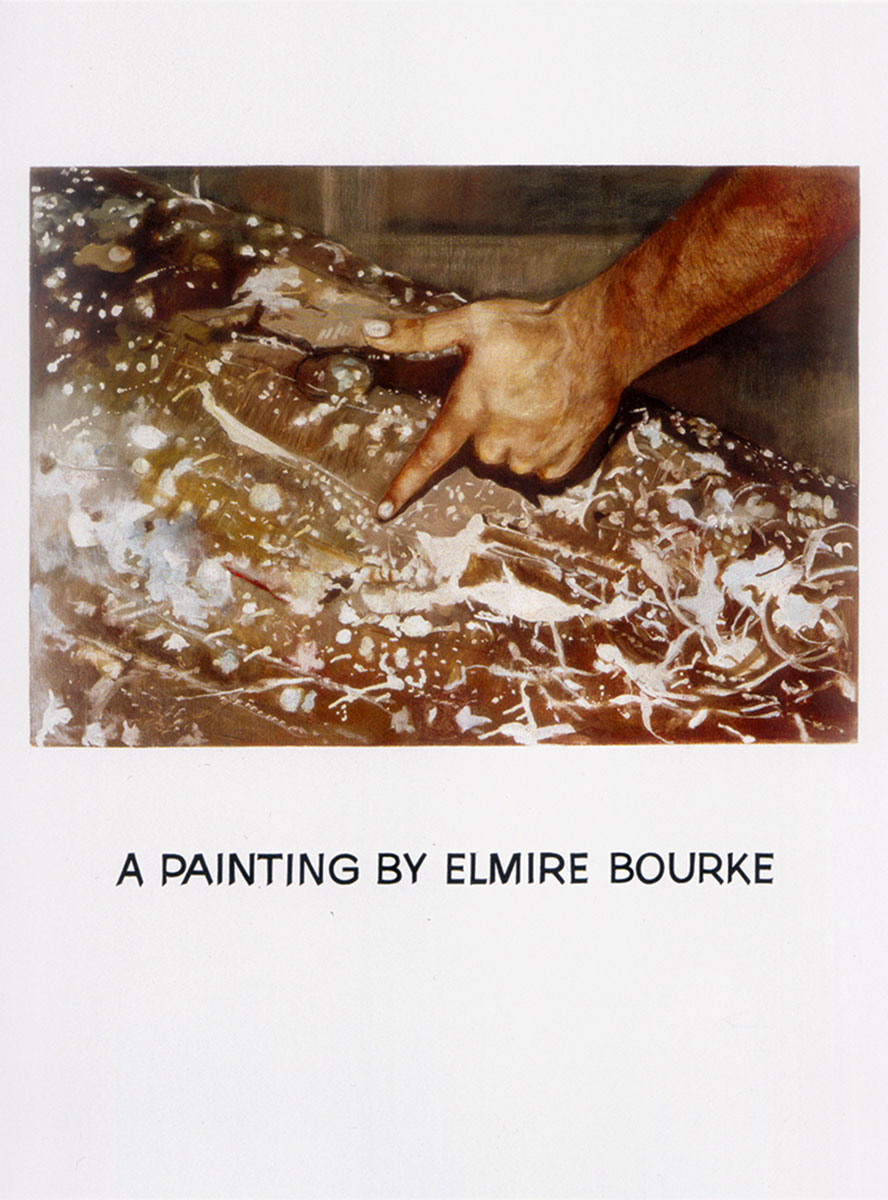

There is something intriguing about the gesture associated with the interesting: pointing. Pointing at something interesting is both vague and precise, and implies that there is more to see than can be seen, that we have recognized something portentous but at the same time are not sure what it is. The gesture is a promissory note, an assertion that this thing will reward further inspection. Does the mute and indicative nature of pointing itself reveal the nature of the interesting?Yes! No one brings this out better than John Baldessari, which is why his A Person Was Asked to Point (1969) played such a central role in my thinking about how the interesting functions as a specifically narrative or diachronic aesthetic—one that unlike the instantaneous thunderbolt of the sublime, tends to unfold in a serial fashion, over time.

Linked always to the relatively small surprise of information, or the perception of minor differences from an existing norm, the interesting is generally bound up with a desire to know and document reality. So we can see why Susan Sontag suggests that it is an aesthetic closely bound up with both the nineteenth-century novel and the history of photography. In On Photography, troubled by how the use of “interesting” as a notoriously weak evaluation tends to promote a general “indiscrimination,” Sontag trenchantly notes that “the practice of photography is now identified with the idea that everything in the world could be made interesting through the camera.” If it is “not altogether wrong to say that there is no such thing as a bad photograph—only less interesting [ones],” the reason why photography becomes “one of the chief means for producing that quality ascribed to things and situations which erases these distinctions” is because “the photographic purchase on the world, with its limitless production of notes on reality,” makes everything comparable to others of its same kind or type.

We can thus glimpse the connection between late twentieth-century conceptualism—famously obsessed with acts of documentation, classification, and the presentation of evidence—and a range of realist practices from the previous century. Indeed, conceptual art’s “crucial innovation,” as Liz Kotz suggests, was its unprecedented pairing of photography with the language of ordinary/everyday observation: the “notes on reality,” and on social types in particular, central also to novelists ranging from Henry James to Georges Perec. As James famously said, “The only obligation to which in advance we may hold a novel, without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting.”

You describe the interesting as a “specifically modern response to novelty and change.” Could you say more about the way in which you think the interesting is a peculiarly historicized affect?

The interesting, like the picturesque, was conceived as an aesthetic explicitly about variation, eclecticism, and idiosyncrasy—as if in unconscious response to the unprecedented proliferation of styles characterizing the late eighteenth-century European marketplace for art. Coinciding with style’s elevation from mere taxonomic concept into primary bearer of an artwork’s meaning, this miscellaneous pluralism would pose a new set of problems or challenges for the modern artist, for whom the act of choosing a style would come to take on unprecedented weight. Schlegel’s interesting is both an effect or byproduct of the rise of stylistic pluralism and an effort to solve the problem, through an explicit embrace of stylistic variation, eclecticism, and hybridity.

Is there a similar historical narrative for curiosity?For a historical narrative about curiosity, I’d refer readers to Hans Blumenberg’s The Legitimacy of the Modern Age, where he traces its significance as the “libido of theory.” Curiosity seems to have been feminized in a way that interest has not—on this see Laura Mulvey’s Fetishism and Curiosity, which, if I recall correctly, reads curiosity as an antidote to fetishism.

The interesting seems more explicitly comparative than curiosity. The fact that we find things interesting only when they seem to differ from others of their type, points to the fact that we live in a world understood as fundamentally taxonomized. This doesn’t mean that it’s a world devoid of wonder or surprise—only one in which, as Mikhail Epstein notes, the unknown must be immediately related to what is already known. In fact, Epstein provocatively argues that the interesting is a way of explicitly using understanding to check wonder; or mitigating the “alterity of the object” with “reason’s capacity to integrate it”—like a scaled-down version of the two phases of the Kantian sublime. In any case, in its efforts to reconcile the individual with the generic, the interesting might be described as an explicit response to the modern routinization of novelty.

It’s also a response to what we might call the mediatization or informatization of reality—to the fact that “the observation of events throughout society now occurs almost at the same time as the events themselves” (as Niklas Luhmann put it). One sees this reflected in conceptual art’s fascination with its coextensiveness with publicity, and also in its fascination with systems, networks, and media.

If the interesting speaks directly to this aspect of modern culture—what Mark Seltzer calls the doubling of everything with its description—it also speaks to what many have noted as the increasing convergence between art and discourse overall. Art’s identification with critical or theoretical discourse about art, in particular, seems to have become one of the most important problems informing the making, dissemination, and reception of art in our time—as important, perhaps, as the loss of the antithesis between the work of art and the commodity. The “merely interesting” conceptual art of the 1960s and 1970s seems to have been a concerted effort to grapple with this.

Adam Jasper is a lecturer in the Faculty of Design, Architecture and Building at the University of Technology Sydney. He is a contributing editor of Cabinet.

Sianne Ngai is professor of English at Stanford University. She is the author of Our Aesthetic Categories (Harvard University Press, forthcoming 2012) and Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2005).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.