Mengele’s Skull

From witness to object

Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman

It was an unusual coincidence, one that presented a difficult choice. Mossad agent Rafi Eitan described the missed opportunity to an interviewer from Der Spiegel almost fifty years later:

In the spring of 1960, as we were planning the arrest of Adolf Eichmann, we learned that [Josef] Mengele was also in Buenos Aires. Our people checked out the address and it proved to be correct. … There were just 11 of us and we had our hands full dealing with Eichmann. After we had brought Eichmann to the house where we kept him until we flew him out, my boss at the Mossad, Isser Harel, called. He wanted us to arrest Mengele as well, but Mengele had left his home in the meantime. Harel said we should wait until he returned and then bring both him and Eichmann to Israel in the same plane. I refused because I didn’t want to endanger the success of the Eichmann operation. … When our agents returned to Argentina, Mengele had moved out of his apartment and gone underground.[1]

So Eichmann went to Jerusalem, and Mengele remained in South America. The first was executed after facing survivors, witnesses, and judges in an Israeli court in 1961 and the second, who died in hiding in Brazil, ended up as a skeleton on the examination table for forensic experts in 1985. Each of these forums exemplifies, and perhaps even inaugurated, different forms and sensibilities within the ethics and epistemology of war crime investigations and human rights.

• • •

The “era of testimony” began, by most accounts, with the trial of Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961, the first major war crimes trial since Nuremberg and Tokyo and the crucible of all the great debates about international criminal justice and accounting for atrocities since.[2] In the two chapters of The Juridical Unconscious devoted to Eichmann, Shoshana Felman argues that the new political agency of survivors as witnesses established at the trial was acquired not in spite of the fact that the stories they told were hard to tell, hear, or sometimes even to believe, not in spite of the fact that they were unreliable, but, paradoxically, precisely because of these flaws. Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Jackson had himself contrasted the bias and faulty memories of witnesses with the solidity of documentary evidence: “The documents could not be accused of partiality, forgetfulness, or invention, and would make the sounder foundation.”[3] In their book Testimony, Felman and Dori Laub had earlier argued that it was often in silence, distortion, confusion, or outright error that trauma—and hence the catastrophic character of certain events—was registered.[4] The frailty of the witness, the unreliability and even at a certain point the impossibility of bearing witness, had become the decisive aspect of testimony, its power to register and convey the horror of events. “Paradoxically, it is precisely the witness’s fragility that is called upon to testify and to bear witness,” wrote Felman.[5] In this sense, as political scientist Michal Givoni has suggested, one of the characteristics of testimony in the context of war crimes is that its ethical function exceeds its epistemic one.[6]

The case of Mengele, though—the path not taken and the trial that never happened—provides an instructive alternative to the story that seems to begin with Eichmann. For when Mengele was finally found, dead, many years later, the investigation that determined his identity opened up what can now be seen as a second narrative, not the story of the witness but that of the thing in the context of war crimes investigation and human rights. If the trial of Eichmann indeed marks the beginning of the era of the witness, we would suggest that the exhumation of a body thought to be that of Mengele in June 1985 signals the inauguration of an era of forensics in human rights and international criminal justice. To better understand the present place of forensic evidence in this context—not only of the exhumations that still go on but also the use of DNA, 3D scans, nanotechnology, and biomedical data in these investigations—we must return to the story of Mengele, where it began.

• • •

The mid-1980s saw what amounted to a last ditch effort by the US, Israeli, and other governments, as well as a range of private voluntary organizations like the Simon Wiesenthal Center, to track down and capture those former Nazi leaders who remained alive. Particularly concerning Mengele, everything seemed to come to a head in 1985. Early in February the US attorney general announced that the Justice Department would begin an investigation which would “compile all credible evidence on the current whereabouts of Mengele as well as information concerning his movements in occupied Germany and his suspected flight to South America.”[7] In May, anticipating the fortieth anniversary of Germany’s defeat, the US, West Germany, and Israel announced a joint effort to find Mengele and bring him to trial for crimes against humanity.[8] Obviously, time was running out for both witnesses and perpetrators.

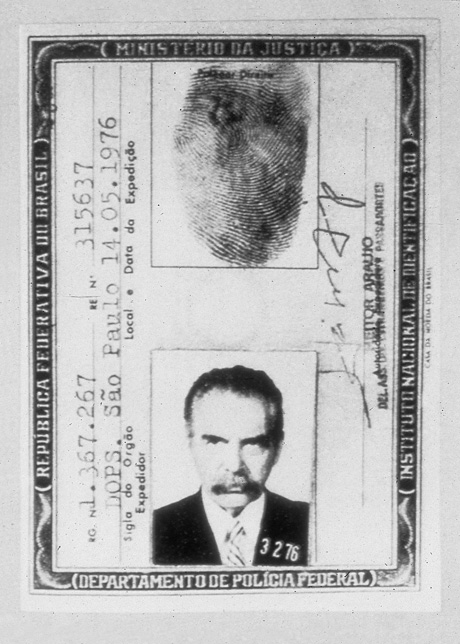

The break in the Mengele case came shortly after that. On the last day of May 1985, based on tips gathered as part of their own investigations, West German police raided a house in Mengele’s home town in Günzberg, Bavaria, and uncovered a trove of documents, including letters with coded return addresses, which pointed them to Brazil and to an Austrian couple named Wolfram and Liselotte Bossert.[9] The Bosserts, who lived in São Paulo, then told police there that they had indeed sheltered Mengele in Brazil, and helped him assume a false identity. They also pointed investigators to what they said was his grave, in the cemetery of a small town outside São Paulo called Embu. He had, they said, drowned at the beach resort of Bertioga in 1979, and they had buried him in Embu under a false name, Wolfgang Gerhard. On June 6th, the Brazilian police exhumed the body.[10]

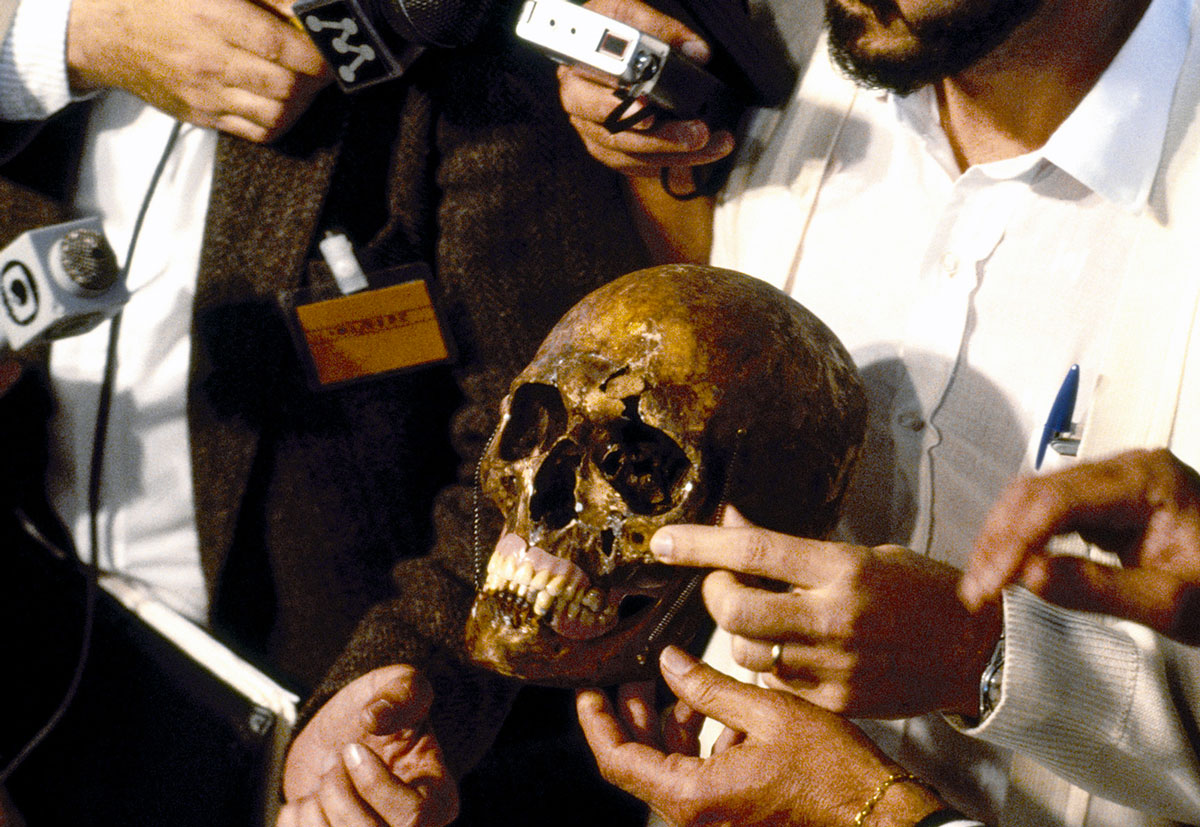

The skeleton that emerged became the center of a major media event. But its status was soon contested. The Brazilian police announced their certainty from the start—Romeu Tuma, the chief of the federal police in São Paulo, holding the skull in his hands, told the cameras at the exhumation site that Mengele “was well and truly dead”—but, obviously, not everyone was convinced that the bones belonged to him.[11] Israeli officials in particular, including Issar Harel, the retired head of Mossad who had overseen the Eichmann kidnapping and the aborted attempts to catch Mengele, were said to believe that “Mengele and friends who may be harboring him had acted after becoming alarmed by the coordinated campaign by the United States, West German and Israeli Governments to bring him to trial.”[12] “We are not going to allow ourselves to be influenced by political or ideological feelings,” said Tuma the next day. “There are some who would like us to say he is still alive, and some who would like us to say he is dead.” Jose Antonio de Mello, the deputy coroner who led the ensuing examination, told reporters, “It will be very, very hard to make a positive identification of the body as being that of Mengele.”[13]

Because of the high stakes of the identification—Mengele was in a sense the last remaining Nazi war criminal of any significance, and his death would effectively put an end to the era of Holocaust trials and to the search for perpetrators—leading forensic analysts from several countries converged on the Medico-Legal Institute labs in São Paulo. Besides the Brazilian investigators, an official American team was dispatched, as well as a West German group, and Israeli officials were also present. The Weisenthal Center sent its own group, including the legendary Oklahoma-based forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow, who after a career in the United States had just begun to train the Argentine students who would go on to become the Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team), the world’s first professional war crimes exhumation team.[14]

The wide array of forensic evidence called for an equally diverse collection of experts: analysts of handwriting, fingerprints, dental records and X-rays, photographs, documents, and clothing were all involved in the investigation.[15] Rather than write parallel reports that would verify or contest each other, they decided to work together. The police chief told the assembled experts, “The Brazilian scientists will sign the final report, but we need your endorsement. … It’s up to you, as scientists, to make the final determination.”[16]

• • •

At the center of the case were the bones. Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover tell the story of the skeleton in three central chapters of Witnesses from the Grave, their account of the career of Clyde Snow and the birth of forensic anthropology in human rights discourse. Stover, chairman of the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Committee on Scientific Freedom and Responsibility, was a member of the Weisenthal Center team, along with Snow, radiologist John Fitzpatrick, and medical examiner Leslie Lukash.[17]

In most forensic examinations of human remains, the question asked of the bones is: how did you die? That is the traditional course of police investigations: the victim’s identity is known, and the cause of death must be established in order to ascertain whether a crime has been committed, and who might have done it. In São Paolo, however, the cause of death was not particularly pertinent. What mattered was to whom the bones belonged.

To answer this question, investigators need to reconstruct the story of a life as it has been recorded or fossilized into the bones. The scientists who converged on São Paulo had before them what was known of Mengele’s biography as it was conveyed in documents, photographs, and medical records. Clyde Snow called his process of work on identifying human remains “osteo-biography,” the biography of bones.[18] He explained that the skeleton contains “a brief but very useful and informative biography of an individual … if you know how to read it.”[19] “Biography” tells us that what is of concern to this kind of reader is not just the moment of death but the entire history of a life—a sequence of illnesses, incidents, and accidents, along with conditions of nutrition, labor, and habit—that is fossilized into the morphology and texture of bones. As one reporter put it at the time, “Success in establishing whether a body exhumed last week in Brazil is that of Nazi war criminal Josef Mengele depends heavily on how much detailed information investigators can gather concerning the living Mengele’s physical characteristics. American forensic medicine specialists said records that describe illnesses, injuries, birth defects, and dental work—plus X-rays and the results of laboratory tests that the former concentration camp doctor may have undergone—vastly improve the chances of making a certain identification.”[20]

The forensic investigation was nothing other than this reading the bones, which moved closer and closer, bone by bone, to an identification: gender (male), handedness (right), height (174 cm), build (medium), race (white), fillings and gaps in the teeth, fractures and accidents marked in new X-rays (of the hip, thumb, shoulder blade, and collar bone), and age at death (64–74 years).[21]

But a “certain identification” was beyond their capacity. Forensic anthropology, like every other life science, is a matter of probability, not certainty. The investigation was a process of elimination in which each interpretation increases or decreases the balance of probability. For scientists and lawyers, truth is measured as a position on a scale of probability. The different questions asked of, and experiments conducted on, the skeleton should be understood as ways of operating within the fuzzy probabilities of forensics.

Instead of a trial of a living person, the process that led to Mengele’s identification was something akin to a “trial of the bones,” a scientific forum in which each claim by any of the scientists was checked and contested by his peers. “We had some members with different backgrounds. But we overlapped so strongly in our knowledge that we could survey and conduct a kind of peer review process within our group, double-checking the findings and methodology of the fellow scientists,” Snow recalled.[22] “After nearly a week’s work,” he said, “we were somewhere between ‘probable’ and ‘highly probable’ that the remains were those of Mengele.”[23]

• • •

Law and science have different methods for determining facts and act differently in relation to probability. And public opinion has its own relation to probability. In this case, forensic science had to convince not only scientists but also government lawyers and criminal investigators, as well as the general public and the survivors.

Forensics is, of course, not simply about science but also about physical objects as they become evidence, things submitted for interpretation in an effort to persuade. Derived from the Latin forensis, the word’s root refers to the “forum,” and the practice and skill of making an argument before a professional, political, or legal gathering. In classical Rome, one such rhetorical skill involved having objects address the forum. Because they do not speak for themselves, there is a need for something like translation or interpretation. A person or a technology must mediate between the object and the forum, to present it and tell its story.

This was then the role of the rhetoricians and today that of the expert witness. The forum is the arena of interpretation where claims and counterclaims have to be made on behalf of things. And it is around disputed or contested things in particular that a forum of debate gathers. In São Paulo, there was no legal forum in the strict sense; it was rather the public, and especially the survivors, that had to be convinced.

Clyde Snow speaks of bones in a rather flamboyant manner. In the manner of a rhetorician employing the trope of prosopopoeia—the figure that artificially endows inanimate objects with a voice—he refers to skeletons as if they were both alive and speaking, and gifted with a special capacity for truthfulness: “Bones make good witnesses. Although they speak softly, they never lie and they never forget.”[24]

But if we are to endow bones with a voice, if they are to become witnesses, they are ones that do not speak for themselves. They need interpretation, translation, and assistance, especially if they are to convince non-specialists or the general public. Forensics is not only about the science of investigation but rather about its presentation to the forum. Indeed, there is an arduous labor of truth-construction embodied in the notion of forensics, one that is conducted with all sorts of scientific, rhetorical, theatrical, and visual mechanisms. It is in the gestures, techniques, and turns of demonstration, whether poetic, dramatic, or narrative, that a forensic aesthetics can make things appear in the world.

• • •

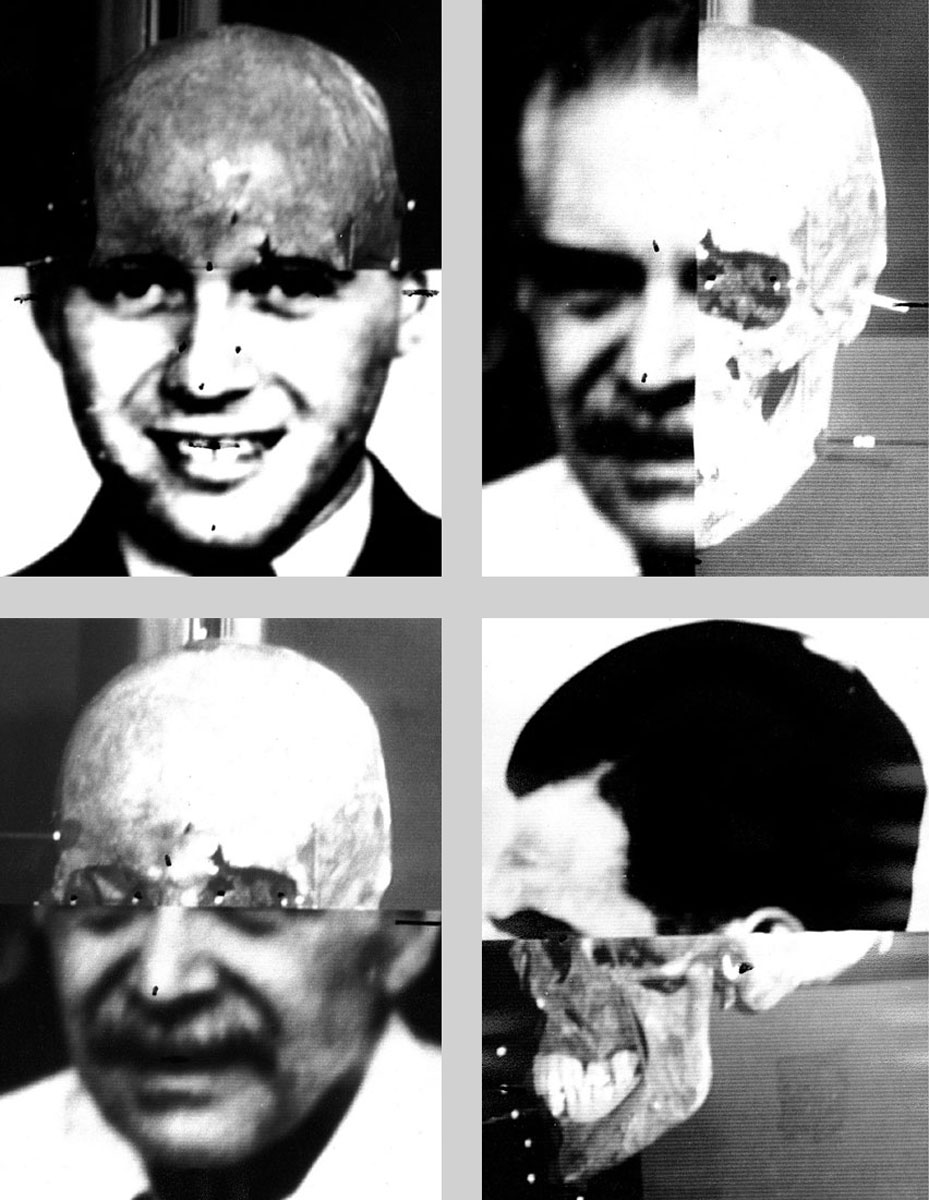

To convince both the scientists and the general public in the Mengele case, an image was necessary, and these images were provided by a member of the West German team, Richard Helmer. First Helmer had to rebuild the skull, which had been badly damaged by the Brazilian police in their hasty exhumation. Once that had been done, Joyce and Stover report, Helmer could get to work on the images:

Hamlet once held aloft a skull and wondered if he could discern its owner’s identity. Helmer now asked himself the same question. But he had at his disposal a technique that Hamlet could not have imagined. … Helmer had perfected a video-imaging process called face-skull superimposition, in which a video image of a photograph is placed over a video image of a skull to determine whether the two are the same person.[25]

Using tables and formulas he had developed of the topography of skulls based on work with hundreds of them, Helmer enhanced the skull to add the thickness and shape of the face which had disappeared with death. Using thirty separate pins, each secured with clay to the surface of the skull and tipped with a white marker at the point where the skin would have been, he recreated the missing contours. This allowed him to compare the skull and the photographs “to the closest millimeter.”[26]

As Joyce and Stover tell the story, the pin-studded skull and the photos were then displayed side-by-side in front of

two high-resolution video cameras … mounted on tracks so that they could slide forward and backward. The video images were relayed to an image processor and from there to a television monitor. Helmer, now scientist turned cameraman, squinted into the viewfinder of one camera, bringing the skull into focus. He moved to the next camera and did the same for the photograph. He shuttled between the two, sliding them back and forth along their tracks until the two images of skull and face on the monitor were the same size. With the image processor, he superimposed the images over each other, lining up the flesh of the face [in the photo] at each pinpoint with the white marker.[27]Having satisfied himself, Helmer presented the work to his colleagues. “The pin-cushion skull came into focus on the television monitor with the photo superimposed onto it. The sight was unnerving. It took a moment for the eye and brain to process the peculiar image. They were seeing a human as no one in life could, as if the skin were a ghostly film.”[28] The match was perfect. It was the image that would convince the public, a photograph wrapped over an object, an image of life over an image of death.[29]

At the press conference the following day, the forensic team presented their conclusions (“it is … our opinion that this skeleton is that of Josef Mengele”)and photographs of their methods, including Helmer’s decisive superimpositions.[30] They also delivered a basic lesson in the status of scientific evidence and truth. Asked how sure they were that the skull belonged to Mengele, US team leader Lowell Levine quoted their determination: “within a reasonable scientific certainty.” “Realizing the ambiguity of the scientific term,” Joyce and Stover say, “he added, ‘That represents a very, very, very high degree of probability. Scientists never say anything is one hundred percent.’”[31]

• • •

It was during the Mengele investigation that the procedures and techniques of forensic identification of human remains were methodologically developed. “That was one of the things we came away from the Mengele case with—a dynamic, ongoing, simultaneous interdisciplinary approach to the problem of identification. A certain analytical method has been effectively developed.”[32]

Snow’s trip to Brazil came immediately following the start of his work with the group of young Argentine anthropologists just beginning to investigate the remains of the disappeared in the “dirty war.” As he tells the story, his bags were not yet unpacked.[33] It was the team in Argentina that would go on to conduct the first large-scale and systematic exhumations in the context of human rights work, producing over many years important evidence in the trials of the junta leaders and developing a pioneering professional expertise in forensic anthropology. Later, they helped disseminate this competence in the killing fields of the 1990s, in places like Guatemala and Chile, but also in Rwanda, Yugoslavia, and elsewhere. Where there was a dispute around a war crime, the graves that had once simply been the space of memory became an epistemic resource.

Modern human rights forensics began in Argentina with the victims, and in Brazil with the perpetrator. And it began with the same question asked of the bones: “Who are you?” Like testimony, forensics has political, ethical, and aesthetic manifestations. The emergence of a forensics aesthetics—marked for us most clearly by Helmer’s video presentation in São Paulo—signals a shift in emphasis from the living to the dead, from subject to object, in the aftermath of atrocity and the pursuit of human rights.

But just as the survivors of the camps required the space of the trial itself to emerge as witnesses, and in a real sense emerged as such in the very act of speaking, so too things do not simply come with their agency already fully operational. A forum, which in this case was a scientific-aesthetic space, and all the techniques of presentation (of making-evident) that come with it, is required for facts to be debated.

If things have begun to speak in the context of war-crimes investigation and human rights, it is not simply that we have acquired better listening skills, or that the forums of discussion have been liberally enlarged. The very entry of bones and other things into these forums has changed the meanings and the practices of discussion themselves. In fact, the entry of non-humans into the field of human rights has transformed it.

See press about “Mengele’s Skull” in Slate.

- Christof Schult, “Wir hätten Mengele töten können” [“We Could Have Killed Mengele: Interview with Mossad Agent”], Der Spiegel, 9 August 2008. Available in English at spiegel.de/international/world/0,1518,576973,00.html, and in German at spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-59889991.html, both accessed 6 September 2011. See also Ralph Blumenthal, “Israeli Tells How He Tracked Mengele in ‘62,” The New York Times, 12 June 1985.

- The phrase “era of testimony” comes from Shoshana Felman, “In an Era of Testimony: Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah,” Yale French Studies, no. 79 (1991), pp. 39–81, and later Annette Wieviorka, The Era of the Witness, trans. Jared Stark (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006), originally published as L’Ère du témoin (Paris: Plon, 1998).

- Quoted in Shoshana Felman, The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002), pp. 132–133.

- Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History (New York and London: Routledge, 1992).

- Shoshana Felman, The Juridical Unconscious, op. cit., p. 134.

- Michal Givoni, “Beyond the Humanitarian/Political Divide: Witnessing and the Making of Humanitarian Ethics,” Journal of Human Rights, vol. 10, no. 1 (2011), pp. 55–75; “Witnessing/Testimony,” Mafte’akh, A Lexical Journal of Political Thought, no. 2 (2010), available at mafteakh.tau.ac.il/en/issue-2e-winter-2011/witnessingtestimony. Accessed 6 September 2011.

- Leslie Maitland Werner, “US Launches Investigation of Mengele Case,” The New York Times, 7 February 1985. See also Thomas Friedman, “Jerusalem Listens to the Victims of Mengele,” The New York Times, 7 February 1985.

- Ralph Blumenthal, “3 Nations Joining to Hunt Mengele,” The New York Times, 11 May 1985; Leslie Maitland Werner, “The Mengele File: US Marshals Join the Hunt,” The New York Times, 28 May 1985.

- Ralph Blumenthal, “Search in Bavaria Led to Exhumation,” The New York Times, 8 June 1985; Alan Riding, [no headline], The New York Times, 9 June 1985.

- Alan Riding, “Exhumed Body in Brazil Said to be Mengele’s,” The New York Times, 7 June 1985.

- Alan Riding, “Key Man in Mengele Case: Romeu Tuma,” The New York Times, 16 June 1985.

- Moshe Brilliant, “Mengele’s Death Doubted in Israel,” The New York Times, 10 June 1985.

- Vincent J. Schodolski, “Old Bones Add A New Chapter To ‘Angel Of Death’ Mystery,” The Chicago Tribune, 9 June 1985.

- Christina Bellelli and Jeffrey Tobin, “Archaeology of the Desaparecidos,” SAA Bulletin, vol. 14, no. 2 (March–April 1996), available at saa.org/portals/0/saa/publications/saabulletin/14-2/SAA9.html [link defunct—Eds.]. Also see “History of EAAF,” available at eaaf.org/founding_of_eaaf [link defunct—Eds.]. Both accessed 6 September 2011.

- Ralph Blumenthal, “Evidence is Said to Point to Mengele Identification,” The New York Times, 20 June 1985.

- Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover, Witnesses from the Grave: The Stories Bones Tell (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1991), p. 169.

- Ibid., pp. 159–163.

- Ibid., p. 140.

- Don Stewart, “Witness After Death,” Sooner Magazine, vol. 6, no. 1 (Fall/Winter 1985), p. 4.

- Harry Nelson, “Mengele Identity Search: How Clues Are Assembled,” The Los Angeles Times, 14 June 1985.

- Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover, Witnesses from the Grave, op. cit., p. 177.

- Clyde Snow interviewed by Eyal Weizman, Dublin, 26 April 2011.

- Eric Stover, “Mengele Id’d by Video Process,” The Chicago Tribune, 12 January 1986.

- Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover, Witnesses from the Grave, op. cit., p. 144.

- Ibid., pp. 193–194.

- Ibid., p. 194.

- Ibid., p. 195.

- Ibid.

- Helmer called his technique “electronic visual mixing.” He published his findings later: Richard P. Helmer, “Identification of the Cadaver Remains of Josef Mengele,” Journal of Forensic Sciences, vol. 32, no. 5 (November 1987), pp. 1622–1644.

- Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover, Witnesses from the Grave, op. cit., p. 200.

- Ibid., p. 202.

- Clyde Snow interviewed by Eyal Weizman, Dublin, 26 April 2011.

- Christopher Joyce and Eric Stover, Witnesses from the Grave, op. cit., p. 160.

Thomas Keenan teaches literature, media, and human rights at Bard College, where he directs the Human Rights Project. He recently curated, with Carles Guerra, “Antiphotojournalism” at La Virreina in Barcelona (2010) and FOAM in Amsterdam (2011).

Eyal Weizman—an editor-at-large of Cabinet—is an architect and a professor of visual cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he also directs the Centre for Research Architecture. A founding member of the architectural collective DAAR in Beit Sahour, Palestine, Weizman also directs the European Research Council–funded project “Forensic Architecture: On the Place of Architecture in International Humanitarian Law,” which includes the themed section of this issue. His books include The Least of all Possible Evils (Nottetempo, 2009; Verso, 2011), Hollow Land (Verso, 2007), and A Civilian Occupation (Verso, 2003).