Reimagining Recreation

The lost world of New York City adventure playgrounds

James Trainor

There was a child went forth every day, / And the first object he looked upon and received with wonder, pity, love, or dread, that object he became, / And that object became part of him for the day, or a certain part of day, or for many years, or stretching cycles of years.

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass, 1856

After all, it was one of his playgrounds, one of the safe, drab, battleship-gray ones whose WPA-era design had changed little since Moses assumed power as New York City’s parks commissioner in 1934 (during his twenty-six-year reign, 650 playgrounds were built). The banal swing set. The bone-jarring seesaw. The galvanized slide. The joyless sprinkler. Each static feature was set far apart from the others, as if to avoid cross-contamination of respective functions, all of it embedded in a vast expanse of summer-blistered asphalt and concrete. I was five years old and with a sizable gash in my forehead, blood streaming down my face (eight stitches, lots of iodine, Roosevelt Hospital emergency room); it was my first and last major mishap in a New York playground, one that instantly implanted a lifelong phobia of pebble-dashed concrete. Along with asphalt (a “resilient” surface, Moses once proudly explained, that prevents children from “digging and eliminates dust”), it was the most unlikely play surface ever concocted by bureaucratic city planners charged with the safety of Gotham’s young. (An artificial agglomerate, it was thought to give traction to little feet running through sprinkler basins, but had the added benefit of acting like a human cheese-grater for unexpectedly airborne kids.)[1]

The obvious irony in all this was that this standard-issue trauma did not occur in what the kids in my Upper West Side neighborhood fondly nicknamed “the dangerous playground” just up the hill—the one that called out with its siren song of massive timbered ziggurats and stepped pyramids with wide undulating slides, the vertiginous fire-pole plunging though tiered treehouses, the Indiana Jones-style rope bridge, the zip line, the Brutalist-Aztec watercourses, and tunnel networks. There, I received not so much as a scratch. And there wasn’t just one dangerous playground; these so-called adventure playgrounds were sprouting up everywhere, siphoning off, Pied-Piper-like, any kid with a scrap of derring-do suddenly bored to death with the old playgrounds, places that now had all the grim appeal of a municipal parking lot.

Throughout my childhood, as I recall it, my parents would take my sister and me on periodic expeditions—every few months, it seemed—to check out the newest adventure playground to open. Large and small, they sprung up in public parks, but also in the ill-used plazas of public housing complexes, school yards, derelict vest-pocket lots between old tenements cleared by fires or demolitions, and reclaimed backyards. There was what people would later call buzz: in February 1972, New York magazine’s plaintively celebratory “101 Signs that the City Isn’t Dying” cited the continuing construction of adventure playgrounds as reason number four to resist the inexorable flight to the suburbs. And in their way, grownups who had come of age under the beneficent, autocratic rule of Moses were as dazzled and beguiled as their kids, slightly wary and unsure, but visibly switched-on in their body language. And the kids could barely contain their manic, unnameable joy, bursting onto the latest labyrinthine landscapes of play like animals reintroduced into the wild.

For a week, the so-called “baby-carriage brigade” successfully outflanked attempts at demolition. Then in the wee hours of Tuesday, 25 April 1956, Moses sent in a work crew that began bulldozing trees before sunrise. The popular outrage was universal, and Moses found himself at the center of a perfect PR disaster, truculently defending the rights of parked cars against the toddlers of a sophisticated, educated, and newly civic-minded voting block. A still-baffled Moses backed down in the face of a court injunction, but not in time to salvage his reputation as the man who “got things done” for the greater public good. The shady knoll proved to be his Waterloo.

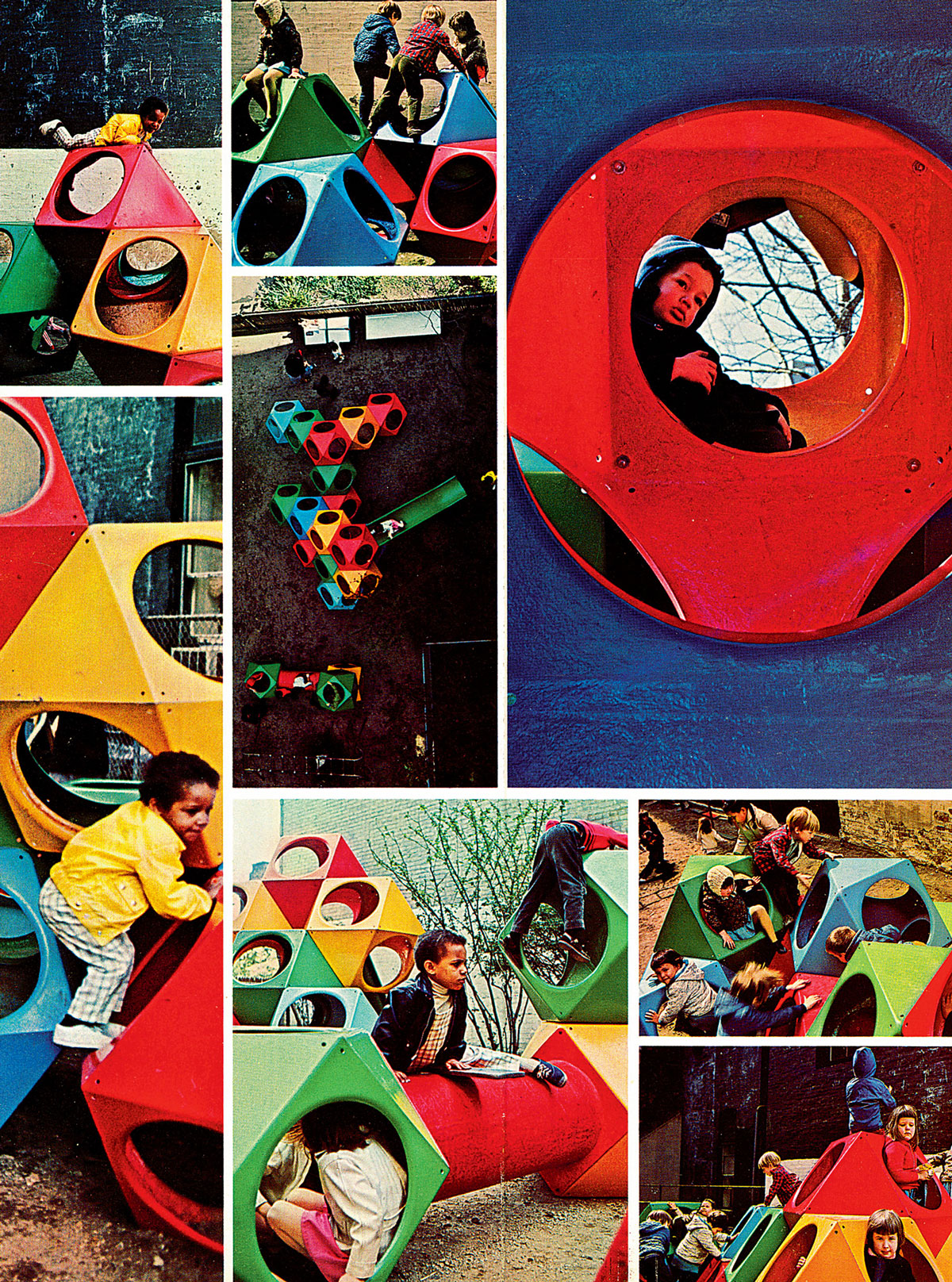

Almost overnight, Dattner and Friedberg became the Young Turks of radical urban playground design, a professional discipline that hadn’t even existed until their respective projects somewhat inadvertently invented it. The act of designing for children suddenly gained an urbane, avant-garde hipness. The two men preferred the term playscape, an important distinction auguring the end of play as a series of dull interactions with one isolated object after another and offering a new conception of creative play as a fluid, freeform, open-ended map of imaginative experiences and sets of decisions, outcomes, and strategies—a differentiation that reflected a revolutionized understanding of the vital importance of play in mental and physical development. Inspired by the work of pioneering child psychologists Jean Piaget and Erik Erikson, among others, and their theories regarding the connection between cognitive development, adaptive intelligence, and play, Dattner and Friedberg both designed environments to unleash children’s natural instincts to choreograph their own experiences through a non-prescribed network of features enabling individual exploration, social interaction, and a dynamic sense of growing mastery over a variety of challenges. Play, as Friedberg noted in his 1970 book Play and Interplay, was not merely an “expenditure of excess energy,” as previous generations had been accustomed to treating it. (He was thinking of Moses’s pronouncement that the primary purpose of a playground was to “intercept children … and provide a place in which excess energy can be worked off without damage to the park surroundings.”[3]) In contrast, play was “essential to a culture”[4] and designers had a civic duty to facilitate opportunities for both children and adults for creative interactions with the urban environment.

Bold, geometric, and unapologetically monumental, the new playscapes were everything the dull and instantly outmoded playgrounds were not. They were the rebellious New Left’s answer to the authoritarian WPA steamroller approach to public recreation. Like the civic awakening that took place a decade before, the new landscapes were about self-empowerment rather than over-determining, one-size-fits-all behaviors. While each of the new play environments was unique, they were constructed using a budget-conscious inventory of inexpensive and durable materials: cobblestones, bricks, telephone pole timbers, nautical rope, wooden planking, galvanized metal pipes, beach sand, formed concrete. They were the elemental materials of old working-class New York—the building blocks favored also by downtown minimalist sculptors with a romantic regard for the perceived authenticity associated with labor and production—repurposed into futuristic designs that seduced both children and adults.

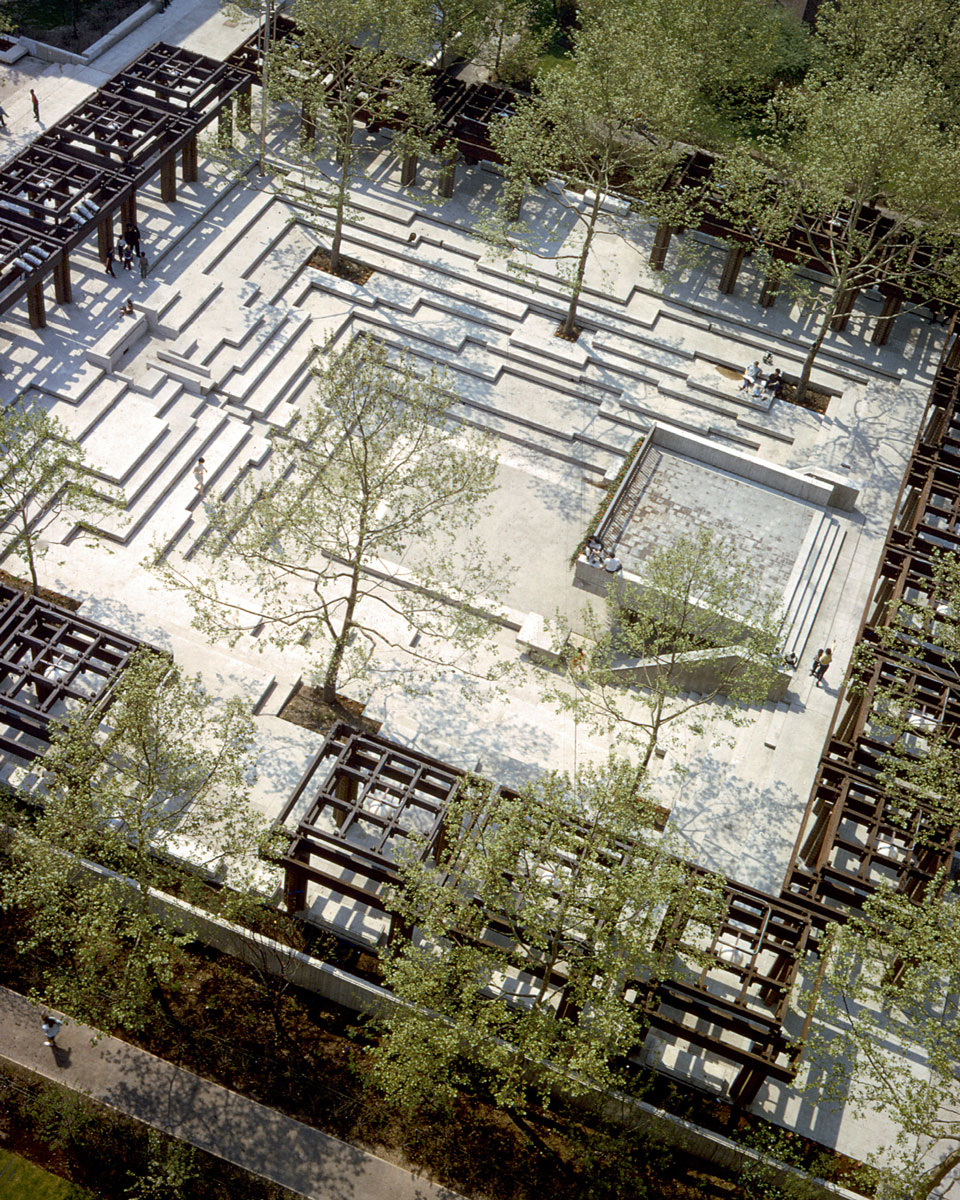

In rapid-fire succession, Dattner received commissions to completely reimagine five of the twenty “necklace” playgrounds dotting the periphery of Central Park. In contrast, Friedberg took aim at the blighted corners of the inner city: the grim, utilitarian spaces of New York’s public housing blocks; rubble-strewn lots on the West Side awaiting “urban renewal” mega-projects; disused public school yards; and the liminal spaces of the city that progressive urbanists like William H. Whyte (a friend of both Friedberg and Dattner) were reconceiving as potential oases.

Along the way, Dattner coined and copyrighted the term streetscape, and you can understand why. In the two years between January 1965 and January 1967, something mutated in the DNA of New York’s urban fabric; in the brief span between the release of the Beatles’ Help and Revolver (a contemporaneous metric of overnight epochal cultural recalibration if ever there was one), the look and feel of the city’s streets changed forever. As architect James Sanders points out in his book Celluloid Skyline, sometime around the start of Mayor John V. Lindsay’s administration in January 1966, official New York stopped behaving like the grudging, gritty industrial city it had been and started acting like a giant outdoor stage for itself, promoting amenities, events, and initiatives that framed the city as a place to be collectively enjoyed, not simply survived. It also openly embraced the concept of fun, and the drama that public pleasure affords in a post-industrial metropolis. In essence, enjoyment of the city became an accepted part of public policy. Usually staid stretches of real estate like Third Avenue suddenly sprouted blobby brick pavement features, while tubular lobby entrances, public loveseats, waterfalls, sculptural super-graphics signage, and building-scaled Pop and Op murals blossomed everywhere. Writing retrospectively in 1972, the architectural critic Peter Blake welcomed the whimsical pedestrian happenings and the new sensibility of “fun and games” that the city had adopted in recent years.[5] Key to this shift was the effervescent Hoving, the soon-to-be Metropolitan Museum of Art director who, as parks commissioner, staked his claim as the anti-Moses on taking office in 1966 by declaring that “the old rinky-dink, hand-me-down stereotype of the park is out, OUT!”[6] Hoving banned traffic from the drives of Central Park on weekends and initiated a series of Alan Kaprow-like Happenings—a massive open-call game of “capture-the-flag” on the Central Park Mall, a communal “paint-in” gathering in Sheep Meadow, kite happenings, folk music happenings, midnight meteor shower happenings—sanctioned events that had a whiff of counterculture about them. The green light he gave to the adventure playground model was one visible aspect of this altered landscape in which the new way to be a New Yorker in an era of youth-oriented media, information, and culture was to “play” the city.

The playscapes were the first in New York to be designed by architects—idealistic, savvy, and ambitious young designers with their own tots in tow, steeped in New Left politics, versed in current social theories and child psychology, and at home in downtown art circles. (Friedberg was a lifelong friend of artist Jackie Ferrara, whose feminist take on post-minimalism featured wooden staircases, ramps, and stacked pyramids that almost invited the viewer to start climbing on them.) Unbeknownst to most, Dattner and Friedberg embodied a small but important vanguard working in parallel and often anticipating the environmentally engaged work of Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Robert Morris, Sol LeWitt, and others. They put into place on the streets, plazas, parks, and backyards of Gotham what New York–based land artists-to-be were beginning to conceive for the American hinterlands. With their raised concentric berms and breastworks, their stark but friendly primal geometries, this was fun brutalist minimalism meeting functional land art, neo-archaic environmental sculpture given meaning through the projection of continually changing children’s narratives. As a point of reference, few remember that the groundbreaking “Primary Structures” exhibition at the Jewish Museum in June 1966, which introduced minimalism to the world before that term had gained any consensual currency, was originally to be given the playful and elemental title “ABC Art.” The show opened one month after the ribbon cutting for Friedberg’s vast, mind-blowing geometric playscape at Jacob Riis Plaza in May 1966. Writing in Art in America in November 1967, Jay Jacobs observed that “after generations of neglect, the public playground is suddenly in the midst of a renascence as designers, sculptors, painters and architects strive to create a new world of color, texture and form [for children].”[7]

Dattner’s book Design for Play (1969), written just three years into his young career, was part quiet manifesto for the new zeitgeist, part diaristic picture-book case study, and part exegesis on how the core principles of the “New Play” could be adapted and expanded by individuals and communities everywhere. In it, he cited not only Piaget and Erikson, but also the British landscape designer and fierce child welfare activist Lady Allen of Hurtwood (an apt honorific given her enthusiastic support for the development of neighborhood “junk” and “rubble” adventure playgrounds in Britain and Scandinavia in the bombed-out postwar years, and her unsettling dictum, “Better a broken bone than a broken spirit”). While studying at the Architectural Association in London, Dattner had befriended Lady Allen and was exposed to a more rough-and-tumble and anarchic precedent for play environments than was imaginable in the US. But Dattner also credited artist Isamu Noguchi for having fully envisioned the concept of the playground as a cohesive sculptural environment long before anyone else, back when few in power would bother to listen. As early as 1934, Noguchi had approached Moses with plans for an elaborate “Play Mountain,” which included a stepped pyramid, biomorphic hills, and hollows and rivulets for running, jumping, and tumbling. Noguchi was promptly shown the door. His proposed “Contoured Playground” in 1941, and “United Nations Playground” (1952) were met with equal scorn. An ambitious collaboration with Louis Kahn in 1961–1963, which went through multiple stages of design and gained the backing of philanthropist Audrey Hess for a site in Riverside Park, ultimately foundered after community members blocked its approval, claiming that residents had not been adequately consulted in the radical redevelopment of the multi-acre site.

Dattner took from the Battle of Central Park and Noguchi’s defeat in Riverside Park an important lesson—from now on, community involvement was key to any project’s success. By the mid-1960s, activist neighborhood groups and politicized residents were flexing newfound muscle, working in parallel to the city and circumventing red-tape to get what they wanted by attracting philanthropists and foundations, raising private funds, rallying supporters, and hiring designers.

In preparation for his 67th Street adventure playground, Dattner drew from his own anthropological research on how contemporary children played in New York, both inside and outside defined playgrounds. After consulting with various experts on childhood development, he led multiple workshops and meetings with neighborhood parents to build consensus, support, and a sense of collaborative involvement with the community. While the bulk of the $85,000 budget was underwritten by the Lauder Foundation, the rest was raised over the course of 1965–1966 though block parties, school bake-sales, and, as Dattner fondly recalls, a spirited picnic in the park accompanied by a folk-rock band of twelve- and thirteen-year-olds. By the time the formed concrete was dry, the community felt like it had always been there, that it belonged to them. The rest is history.

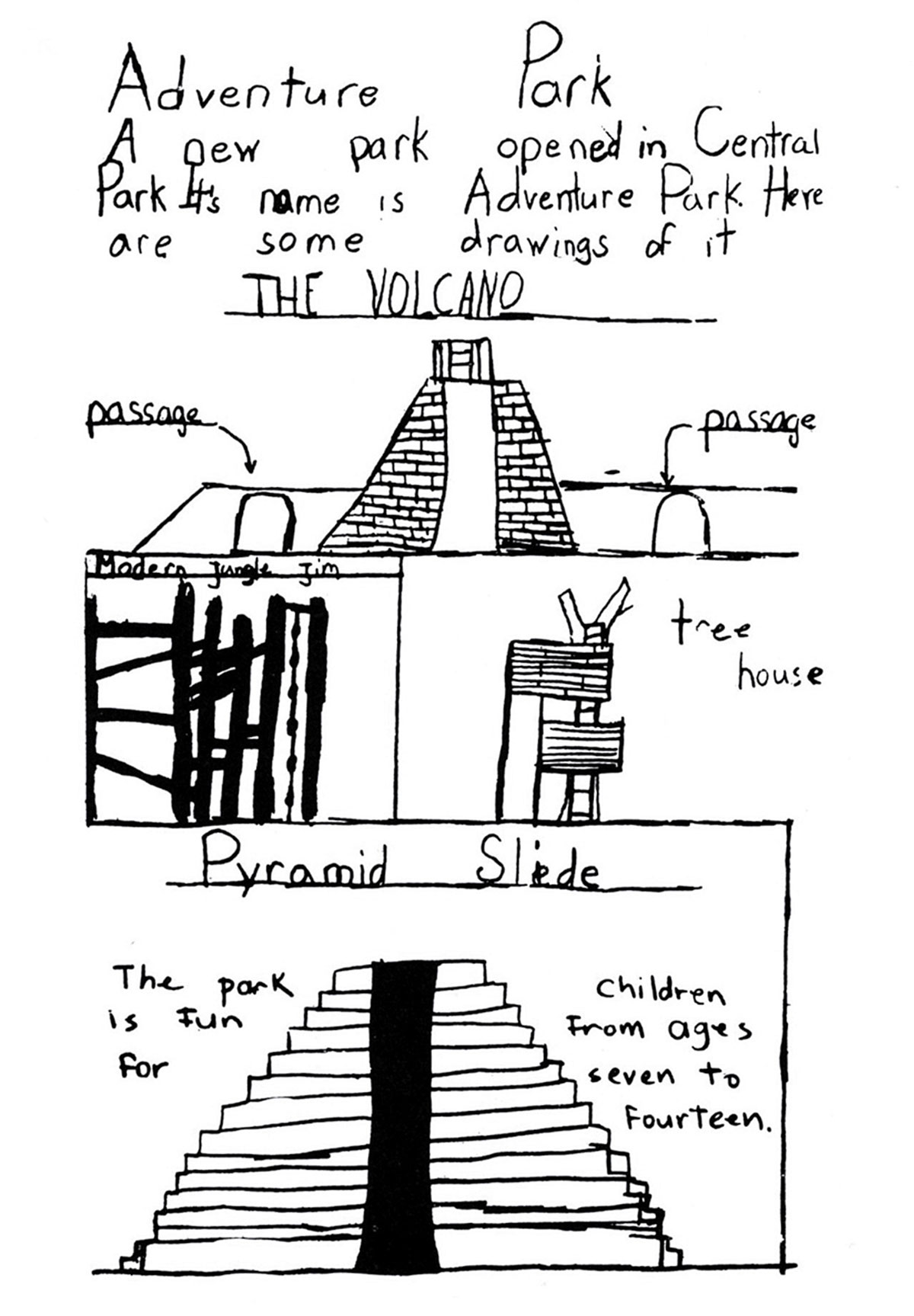

The Volcano

Passage

Modern Jungle Jim

Tree House

Pyramid Slide

Like any good pop poster of the era, the mimeographed drawing deftly fixed certain iconic forms in the mind, and set the tone for cataloguing the dizzying array of playful designs that Dattner, Friedberg, and their peers would begin rapidly deploying across the city over the coming years—cobblestone igloos; mounds and brick mesas; coffered pyramids with vertical laddered tunnels; steel slides; circular parapets; brutalist grottoes; concentric circular ramparts and stone mazes; conical volcanoes; stepped ziggurats; tiered amphitheaters; helixical mountains; neo-Aztec watercourses; splashing basins; Sol LeWitt-like climbing block piles; arching steel ladders; timbered plankwalks; nylon spiderwebs; rope bridges; modular interlocking concrete cubes; and fiberglass polyhedrons and cuboctahedra.

Friedberg’s favorite configuration was a Buckminster Fuller-esque geodesic jungle-gym with a pendant tire-swing set within a sand-floored stone crater, all atop a cobblestone mastaba. He used it for both the P.S. 166 playground on what had been a vacant lot on West 87th Street (1967), and at Jacob Riis Plaza, the apotheosis of his work for public housing in its masterful integration of play for children and recreation and community activities for adults. One month after a grand opening ceremony in May 19966 important enough to draw philanthropist Brooke Astor and First Lady “Lady Bird” Johnson, summer started early and the New York Times—with somewhat unaccustomed giddiness—was celebrating Riis as the first playground where kids could “Just ‘Let Go,’” and documenting such brand new games as “No Touching the Ground,” “Hot Peas and Butter,” and “Round-Up.”[8]

Five men, all in their twenties and thirties, sit on park benches and reminisce for the benefit of a stranger.

Guy #1: This used to be a stone playground. All stone [gesturing to take in a 360-degree sweep of the uneventful plaza] everywhere. You know, like the way streets in the city used to be. Stones. Over there, THAT was the giant igloo. Down that way: that was the amphitheater. And next to it, there, was the Cigarette Box.

Stranger: The what?

Guy #1: The Cigarette Box. That’s what we called it. This big box with water coming out of it. That over there [gesturing at the totems with Gottlieb-like abstract hieroglyphics that survived demolition in the 1990s] is the Monument. They’re all that’s left.

Stranger: What happened to the playground?

Guy #1: Aw, you know. They didn’t take care of it. It got old and messed up.

Guy #2: That was the nursery. It’s not a nursery anymore.

Guy #3: Yeah, it was more fun then. We used to play basketball using the wooden beams. I broke my femur bone. I was playing “Don’t Touch the Ground” [a game invented and named within a month of the playground’s opening was still a rite of passage a generation later] and I touched the ground! It was rough.

Guy #1: But things are too safe now. [Much nodding.] These kids are spoiled! All this rubber n’ shit! [They all laugh in agreement to this, pointing at the 2011-edition five-year-olds playing nearby on bright molded plastic equipment.]

Guy #2: You wouldn’t believe it. Ask anyone here. Google it. Everyone remembers it.

The adventure playgrounds were undone in part by the social ills they were idealistically created to address. The city’s fiscal implosion in the 1970s led to a withdrawal of funding for adequate maintenance and supervision, and to the somewhat faulty perception among a bewildered public increasingly fearful of a chaotic atmosphere of crime, vandalism, and drug abuse that the playscapes themselves were to blame for their misuse. Innovations once championed were now seen as part of the problem. Every syringe or condom rumored to have been found in a sandbox, every urban legend of molesters and junkies lurking in the tunnels, led to the conviction that the designs themselves had failed and were actively threatening the city’s children. If public space is seen as permissive rather than liberating, then each tumble, bruise, and scrape is symptomatic of an encroaching anarchy. Not coincidentally, by the 1990s the culture of parenting had changed, reflecting a broad shift in expectations about safety and danger. The elimination of risk and chance, not only from play but from nearly every aspect of a child’s lived experience, seemed an attainable societal goal. The subsequent fear of litigation and increasingly stringent federal safety codes tipped the balance and the playgrounds suffered a slow, largely unsung death by closure, “upgrading,” and invasive renovation.

In the case of Friedberg’s landscapes—from little-known gems such as the 94th Street Backyard Playground to Jacob Riis—it meant outright active erasure. Found in low-income contexts and having suffered the most from neglect and vandalism, they had few powerful advocates to argue for their preservation. Dattner fared slightly better: when the neo-Victorians at the Central Park Conservancy announced plans to raze the original 67th Street adventure playground and four others around the park in 1995, the affluent neighborhood groups and the Landmarks Preservation Commission protested. A compromise was reached, allowing Dattner to consult and supervise their code-satisfying, if often intrusive, facelifts. Elsewhere, into the early years of this century, 1960s-era playspaces large and small quietly succumbed to an anti-modernist backlash of good intentions, as one feature after another was replaced by bright, colorful, mass-produced play-set ensembles not only compliant with all safety codes and the Americans with Disabilities Act but also fully insured by their distant manufacturers. Thus schools and municipalities were absolved from any liability for injury, and what emerged was the landscape of sameness that we recognize today, with a playground on Delancey Street identical to any found in Akron or Fresno. Like brand new Fisher-Price toys, there they sit, with plenty of access for caregivers to hover and dote. And that’s the playground we know: the safe one.

By the end of 2011, there were discernible signs that a backlash to the counter-revolution was emerging. In Battery Park City, the removal of a solitary, recently installed tire-swing (that emblem of 1960s urban play freedom) after a child bumped her head became something of a bellwether, inspiring widespread mockery of what was seen as a farcical overreaction by a handful of Tribeca uber-moms and the neighborhood’s grousing safety militias. The manner in which the “evil tire-swing” controversy was ridiculed by the press and many locals alike (the Gothamist’s editors satirically predicted that wiffle-ball and freeze tag would inevitably join the roster of silent killers of the schoolyard) suggested the possibility that “fear fatigue” had set in even among a hypergentry preoccupied with curating their kids’ childhoods. The popularity of the nearby Teardrop Park (2009), a craggy 1.8-acre urban mountainscape of boulders, water features, the longest steel slide in the city, and more than a handful of real dangers to be sidestepped, suggested that local parents were drinking the same 1967-era Kool-Aid that designer Michael Van Valkenburgh had been sipping while dreaming up his eco-friendly, code-compliant landscape.

All bets are off as to whether these isolated pockets of revival will produce a significant change in urban play sensibilities, but as for the original adventure playgrounds, what’s gone is gone. The revolution was briefly televised (the pilot episode of Sesame Street, aired in November 1969, opened with scenes of kids cavorting in Jacob Riis Plaza), but was abruptly cancelled, and Dattner and Friedberg are happy to be out of the game. Friedberg is busy designing a civic center in India, and when I ask Dattner why he doesn’t design for play anymore, he pauses and looks up at the acoustic tiles on his office ceiling. “Lawyers, lawyers, lawyers!” he declares with a laugh.[9] He now builds, among other things, elementary schools, but he keeps tabs on the current state of playground design (he likes Teardrop Park for mashing up Olmstedian naturalism with raw minimalist thrills). And citing Article 4, Section 43 of the New York City Charter, a newly enforced law making it illegal to enter a playground in New York City unaccompanied by a minor, Dattner admitted that he felt somewhat criminal walking into his own renovated and still-beloved 67th Street playground recently to check on conditions there. The crime is punishable by up to ninety days in jail or a maximum $1,000 fine, and in the summer of 2011, police hoping to meet their quotas ticketed several lawbreakers, including an elderly lady reading a book and eating her lunch in a Brooklyn playground because she felt safer there. Safety is relative.

Kid #1: Why are you here? Do you have kids? What are you doing? [Slight Village of the Damned-like malevolent innocence].

Adult: Um, playing? [Suddenly feeling eminently suspect despite an official press letter in jacket pocket].

Kid #1: Are you a kid?

Adult: No.

Kid #2: This playground is for people with kids.

Adult: Really? Oh.

Kid #1: Once one guy came and was giving out candy and the police came and took him away.

Adult: Right. [Pause] Did you know these used to be play tunnels? Here. They bricked them up a long time ago. See? You could climb through them and then along there and up the volcano.

Kid: #2: You know what? A raccoon came inside the playground once. They took him away too. If I could, I would open up the tunnels and chase the raccoons in there and then chase them away. [The interview apparently concluded, both kids simultaneously leap off the concrete bridge into the deep, syringe-free sand, gaining traction as they tear off towards the great pyramid in the distance.]

See press about “Reimagining Recreation” on thefunambulist.net.

- The young New Journalism essayist John McPhee, writing anonymously in “The Talk of the Town” in a May 1966 issue of the New Yorker, quoted the new parks commissioner Thomas Hoving as saying that the “unimaginative designers who planned these things almost never visited the sites.” See The New Yorker, 28 May 1966, pp. 28–31.

- It happened to be Roselle Springer, the second wife of painter Stuart Davis, with their two-year-old son, George Earl.

- As quoted in Michael Gotkin, “The Politics of Play,” in Charles A. Birnbaum, ed., Preserving Modern Landscape Architecture (New York: Spacemakers Press, 1999), pp. 60–64.

- In conversation with the author, November 2011.

- Peter Blake, “Sky Scrapings,” New York, vol. 5, no. 37 (11 September 1972), pp. 64–65.

- As quoted in James Sanders, “Adventure Playground: John V. Lindsay and the Transformation of Modern New York,” Design Observer, 4 May 2010. Available at placesjournal.org/article/john-lindsay-adventure-playground-new-york/.

- Jay Jacobs, “Projects for Playgrounds,” Art in America, vol. 55, no. 6 (November/December 1967), p. 39.

- Philip H. Dougherty, “On a Hot Day a Kid Can Go to the Riis Playground and Just ‘Let Go,’” The New York Times, 21 June 1966.

- In conversation with the author, October 2011.

James Trainor writes about contemporary culture. His work has appeared in Artforum, Frieze, Art in America, Border Crossings, Metropolis, Programma, and other periodicals. He lives in New York City.