Shaved Heads, Snipped Tubes, Imperial Marines, and Dope Fiends

The fall and rise and fall of Chuck Dederich and Synanon

George Pendle

Can a false god deliver real miracles? Take the case of Charles E. Dederich, better known as Chuck. A more unlikely figure of divinity would be hard to imagine. Born in Toledo, Ohio, in 1913, Dederich’s early years were spent staggering through the American wilderness in a drunken haze. He flunked out of Notre Dame, was fired from his job at Gulf Oil, married and divorced twice, lost touch with his children, and slipped into what he termed “a holocaust of boredom.” By the mid-1950s, he was a wino stumbling along the beach in Santa Monica, California, without friends or family to help him.

Somehow he was shepherded into an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, and it was here that his special nature began to reveal itself. Dederich studiously worked his way through the Twelve-Step Program, admitting that he was “powerless over alcohol” and reluctantly accepting that a “higher power” was all that could restore him to sobriety. Although he was wary of AA’s woozy spirituality, he was enamored of and energized by the family-like dynamic of mutual support.

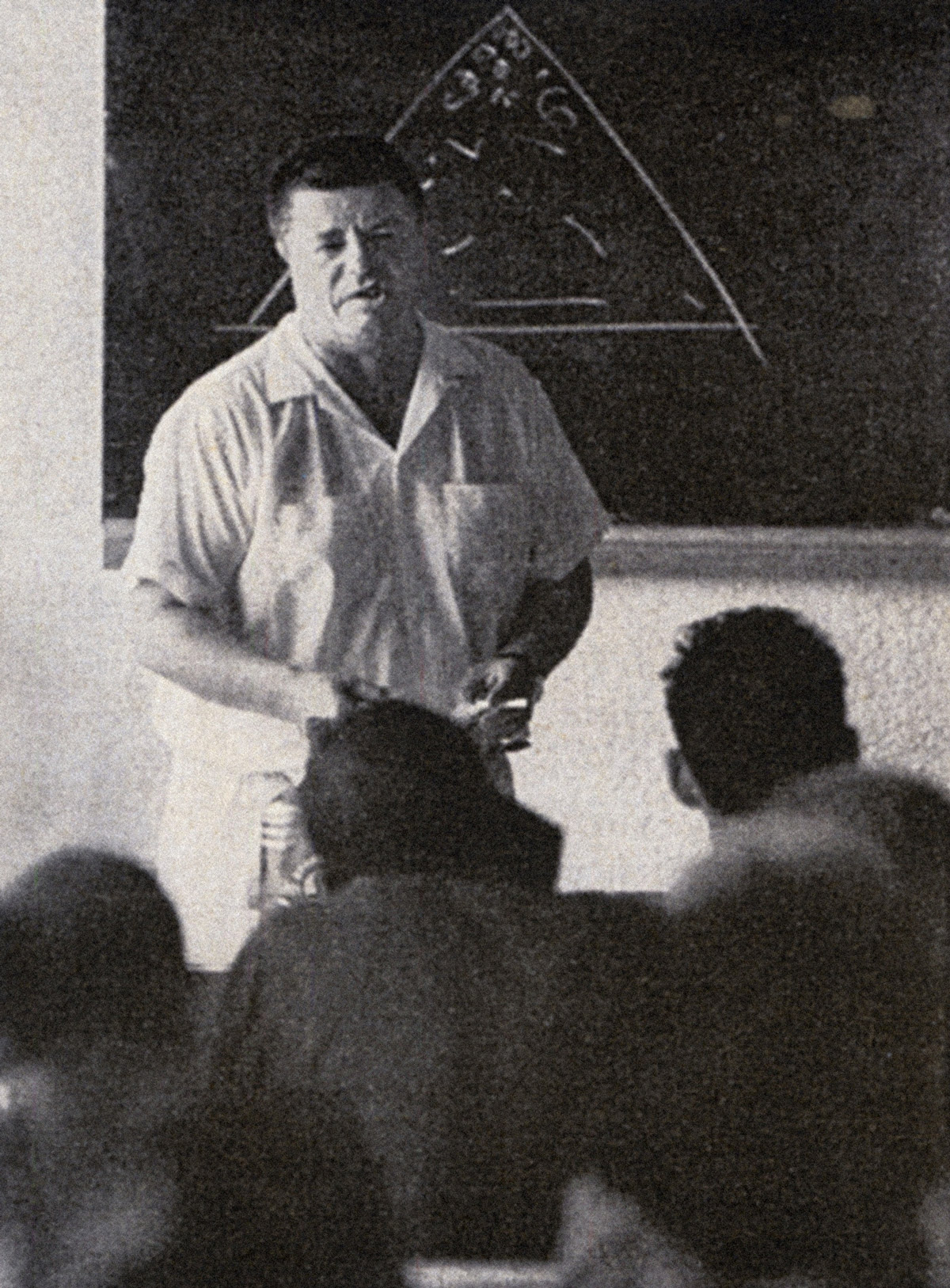

A large man with pale white skin seemingly untouched by the California sun, Dederich’s face had been partially paralyzed by a bout of meningitis, leaving him with a tic and a sneer. He spoke in a raspy, bullfrog croak. But the rough eloquence that burst forth from him at meetings belied his intimidating appearance. He was insightful yet funny, philosophical yet colloquial, and, above all, he was brutally honest with both others and himself. He quickly became a favorite speaker within the Santa Monica group.

Embracing AA whole-heartedly, Dederich began helping others like himself, talking them sober and bullying them into giving up the bottle. He was good at it too, and began inviting AA members back to his apartment after meetings to eat soup, drink coffee, and engage in informal “bull sessions.” He may have been living on welfare, sleeping in fleabag boarding houses, and barely able to afford a meal a day, but he was sober and content. Fate, however, had greater things in store for him.

In August 1957, the University of California was searching for therapeutic uses for the new wonder drug, LSD. The researchers who had tried the drug had been amazed by the spiritual vistas it opened to them and the profound change in outlook it afforded. With this in mind, it was thought that alcoholics, especially those drawn from AA, could receive the greatest therapeutic benefits since they had already given themselves over to “a higher power” and would thus be more open to the beneficent effects of an outside force. In need of money, Dederich volunteered.

Yet while the other volunteers endured sensory enhancements and hallucinations, Dederich experienced none of these. Instead, he recalled having only “feelings of omnipotence and omniscience.” Dederich had finally found a higher power he could be comfortable accepting. It was himself.

• • •

Soon the number of people wanting to join Dederich’s after-hours sessions grew too big for his living quarters. This was largely due to an influx of drug addicts who had heard of Dederich’s ability to keep people straight. For the addicts, Dederich offered their only chance of salvation. AA didn’t want them and the state offered only hospitalization or prison. Sympathetic to their need, Dederich scraped together some cash and rented an old store on whose front he painted the letters TLC, short for “Tender Loving Care.”

The store was a safe place in which drugs, alcohol, and violence were forbidden. But the reason for going there was Dederich himself. Following the LSD experiment, he had become an awesome presence. He held seminars now in which he would talk for hours on end, weaving psychological and philosophical insights together and ridiculing, cajoling, teasing, and harrying the addicts who surrounded him. And most amazingly, it seemed to be working. When one addict slurred the words seminar and symposium together, Dederich suddenly had a name for his project—Synanon. It was a word redolent of “sin,” “Zion,” and, of course, “Alcoholics Anonymous.”

“I knew something,” remembered Dederich, “and I wanted to transmit this to other people. I had the feeling I could really make people more comfortable.” He would choose to do this by making them profoundly uncomfortable. Combining AA’s teachings with the cursory knowledge he had of psychiatry and a heavy dose of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay “Self-Reliance,” Dederich took his natural loquacity and love of rhetorical combat and created a sort of moonshine therapy, a form of treatment that would live on long after Synanon was destroyed and Dederich was disgraced. It was known as the Game.

The Game consisted of a dozen or so addicts sitting in a circle. One player would start talking about the appearance or behavior of another, picking out their defects and criticizing their character. But as soon as the subject of the attack tried to defend him- or herself, other players would join the barrage, unleashing a no-holds-barred verbal onslaught. Vulgarity was encouraged—“talk dirty and live clean,” said Dederich—and so the other members would accuse the defendant of real and imagined crimes, of being selfish, unthinking, of being a no-good, ugly, diseased cocksucker who was too weak to go straight and was too much of an asshole, junkie, cry-baby motherfucker to admit it. Faced with this unrelenting group assault, the recipient would eventually have little choice but to admit their wrongdoing and promise to mend their ways. Then the group would turn to the next person and begin all over again.

“The first time it hits you, it absolutely destroys you,” remembered a former Game player. “No matter how loud you scream, they can scream louder,” recalled another, “and no matter how long you talk, when you run out of breath they’re there to start raving again at you. And laughing.” Emotional catharsis was the aim. There were only two rules: no drugs, and no physical violence. It was vicious, but it actually seemed to work. “One cannot get up,” remarked Dederich, “until he’s knocked down.”

• • •

In the late 1950s, the perils of drug addiction had become a national preoccupation. Everyday the newspapers spoke of the havoc the “dope monster” was causing the United States. The newly elected governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, declared that 50 percent of all crimes in his state could be linked to drugs. Thus, when Dederich moved Synanon to a huge red-brick building on the Santa Monica beachfront and began to populate it with drug addicts, it was unsurprising that it should raise the ire of his neighbors. The local government tried to shut Synanon down repeatedly. Dederich even went to prison for a month for a host of zoning violations, but this only increased public awareness of his “tough love” campaign. Donations started to flood in.

By now Syanon had a routine. New members quit cold turkey and were then slowly ushered into the building’s life. There was hard physical labor, constant mutual support, and the Game, played three times a week. Coffee, peanut butter sandwiches, and cigarettes were always available. There were classes in public speaking, art, drama, and music to keep the members entertained. (Some of the great jazz musicians of the age ended up at Synanon, cutting an album entitled Sounds of Synanon. The first song was entitled “C. E. D.” after Dederich’s initials.) Equally revolutionary was the interracial nature of the place, with Dederich leading the way through his marriage to Betty, a former heroin addict and prostitute who was African-American.

As long as people worked—washing dishes, waxing floors, ironing laundry, painting walls, picking up food donations—they never had to leave. Synanon was also self-policed. You were expected to report those breaking the rules. Those who slacked off, or failed to tell on someone else, were taken to task in the Game. Those who smuggled in contraband were given a “haircut,” a private dressing down from a senior member. Repeated infractions led to banishment.

But perhaps Synanon’s greatest innovation was realizing that addicts knew more about addiction than medical specialists. The dope fiend, as Dederich insisted they be known, was painfully familiar with the tactics of denial and evasion that their colleagues used. What’s more, they shared the same language. There was no “we–they” in Synanon. Here, if you spoke about caps and bennies, turp and horse, everyone knew what you were talking about.

As for Dederich, he was never coy about his role. “I am considered a megalomaniac nut,” he declared. “Of course, this is true, but I’m not so crazy.” He freely admitted to populating Synanon’s board of directors with recovering addicts whom he could control. But no one doubted that this was wise and canny thinking; after all, these were dope fiends and Dederich was entering uncharted territory. Dederich predicted that within three to five years at Synanon, a dope fiend would be ready to “graduate” back to the outside world. No one doubted Dederich’s sincerity, nor worried about the ambiguous undertones to his most famous maxim, the one that he told to each new arrival at Synanon: “Today is the first day of the rest of your life.”

• • •

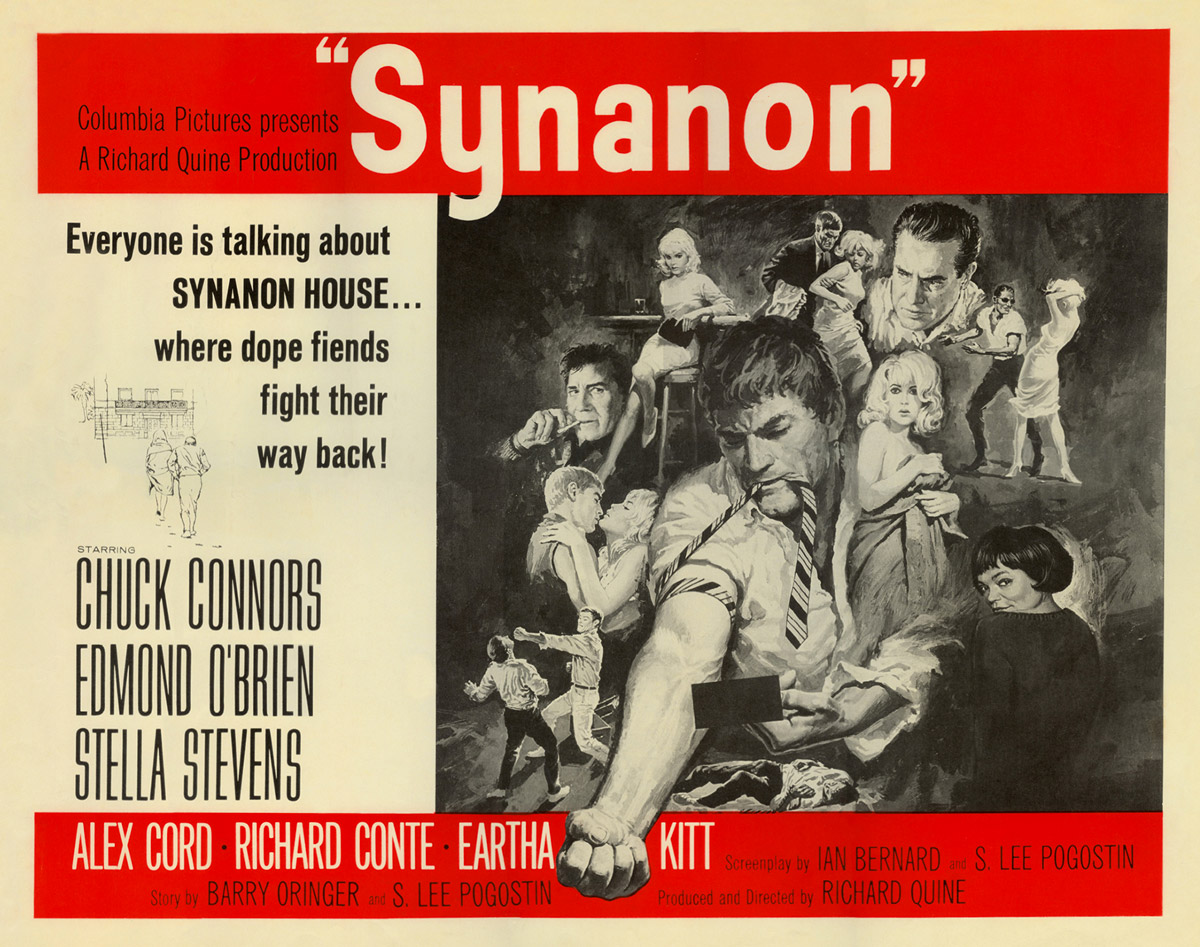

By 1969, Synanon had become a phenomenon. A Hollywood film had been made about it (one tagline read: “Dope fiends scream the truth ... about the house where they live together ... love together ... while they fight their way back!”). It had been referred to in the House of Representatives as “the Miracle on The Beach.” The psychologist Abraham Maslow had praised it, lauding its “no-crap therapy,” and it had become an accepted part of the rehabilitative landscape with courts now routinely sending addicts to Synanon as a condition of their parole.

Such was its fame, and such was the 1960s fascination with communal living, that it had started attracting not just addicts but fee-paying “squares,” people who wanted to live at Synanon simply to be a part of its self-actualization community. With a membership now close to one thousand, Synanon was buying and developing properties in Tomales Bay, north of San Francisco, and in the isolated town of Badger in Northern California. Yet as a reaction to the influx of new recruits, Synanon was growing increasingly proscriptive.

When members stepped out of line now, the “haircuts” they received were literal ones, with men having their heads shaved for bad behavior and women being forced to wear stocking caps. Whereas sex was rampant in Synanon’s early days, now members had to ask a Synanon “elder” for permission to date and were forced to follow a strict and celibate courting ritual. “Glut raids” were routinely run on residents’ rooms to confiscate excessive personal possessions, and Dederich and his elders would instigate arbitrary new rules such as the “twenty-four-hour day” in which half of Synanon would go to work at night while the other half worked during the day. A Synanon police force patrolled the nearby streets looking for members who might be breaking the rules.

The jazz saxophonist Art Pepper, who had spent years in San Quentin on drug charges, checked himself into Synanon in 1969. Suspicious of the culture of self-policing, not to mention the intentions of Dederich (whom he termed “the Old Wino”), he nevertheless understood the need for constant fluctuations in schedule. “Dopefiends and nuts can’t stand routine and when they get bored they have to do something crazy, so Synanon made the insanity. Themselves. The people that ran it caused the insanity.”

No matter how much changed at Synanon, the Game remained at its center. Indeed, even the cynical Pepper quickly became addicted to its verbal volleys. What’s more, Dederich had created variations on it. He now ordered groups to occasionally engage in a forty-eight-hour-long Game called the Trip. The lack of sleep, combined with endless hectoring and supplemented by the use of a Ouija board, led exhausted members to break down and experience hallucinations. Some even declared Dederich their god and savior.

But Dederich was a troubled god. He was issuing ever more “containment” orders, forbidding residents to leave Synanon buildings and growing increasingly fevered in his demonization of those who quit the program, labeling them “splittees.” The fact was that he was seeing many of Synanon’s recent graduates relapse into drug use. Addicts would only stay clean, it seemed, if they remained under his direct control within the walls of the complex. Rather than encourage his members to graduate, Dederich was wondering if the best thing might be to make them stay within Synanon forever.

• • •

As his isolationist sentiments grew, Synanon increasingly began to act as a macrocosm of Dederich himself. When health problems forced him to give up sugar and refined grains, the offending foodstuffs were quickly removed from the Synanon kitchens. When he started running in place to try and lose weight, it quickly became compulsory for everyone to join him in this activity. When Dederich shaved his head, within hours everyone had shaved their head (or had it forcibly shaved) as a sign of solidarity. Most controversially, when Dederich’s doctors advised he give up smoking, an order was issued banning cigarettes. The gravity of this ruling should not be underestimated. Ever since the organization’s founding, coffee and cigarettes had been the only chemical buffer between recovering addicts and the abyss of addiction. The smoking ban led to 150 members quitting on the spot.

But Dederich didn’t care. Synanon was growing rich. By 1972, there were 1,700 live-in residents, who were either paying monthly dues or working for almost nothing. Dederich was receiving bequests. A wealthy woman resident donated $1 million to the cause. Another member gave Synanon control of his mortgage company. Added to this was Synanon’s hugely profitable business manufacturing corporate merchandising gimmicks—ballpoint pens, wallets, T-shirts. It was the second largest such firm in the United States. Founded to get people off junk, Synanon was now creating it. Soon, Synanon owned properties across America; at Tomales Bay, it had a fleet of ships, and at the Badger property hundreds of motorbikes and trucks, not to mention an airstrip and a private plane. It was also there that a luxurious complex known as the Homeplace was being constructed. Boasting hot tubs and riding stables, this was where Dederich, his wife Betty, and some of Synanon’s elders could most often be found. The rank and file lived half a mile away in army-style barracks.

There were battles along the way, but each one seemed to strengthen Synanon, and increase Dederich’s suspicion of the outside world. In 1972, the San Francisco Examiner published a series of critical articles about the organization’s increasingly eccentric character. Dederich sued. By this time, his group had a legal staff of forty-eight drawn from its residents, which included class-topping, Harvard-educated lawyers. Hearst Newspapers settled out of court for $2.6 million. Similarly, when the IRS challenged Synanon’s tax-exempt status, arguing that it was no longer a drug rehabilitation center but an experimental society, Dederich one-upped them and declared it a religion. This exempted the organization from all income tax and sidestepped the increasingly hostile attempts by various state legislatures to license it. Still more conveniently, it allowed Dederich to shrug off the difficult questions he was being asked by members as to when they might be “graduating” from Synanon. “Nobody ‘graduates’ from a religion,” wrote one of Synanon’s lawyers. Dederich’s apotheosis was complete.

• • •

In the summer of 1973, an incident would occur that would profoundly change the Synanon community forever. Dederich himself was taking part in a Game, but one female member was showing him no respect and kept interrupting his gnomic utterances. Infuriated, Dederich stood up, walked over to the woman, and poured a can of root beer over her head.

It was a small gesture of frustration, but the effect within Synanon was earth-shattering. No matter the other changes that had taken place, the rules of the Game had always been sacrosanct—no drugs, no violence. Now Dederich himself had broken one of them. Some wondered whether he’d gone crazy, but his more devoted followers preferred to see it as a sign, as a call to arms.

Just as the outside world had been slow to embrace Synanon, it was now slow to let go of it, despite the turn away from non-violence. In fact, soon after the root beer incident, juvenile courts started sending troubled children to Synanon. Unlike the other residents, many of these children had no wish to change their ways, and in the past, this “Punk Squad,” as they became known, would have proved impossible to control. But unfortunately for them, Dederich had shown that the gloves were now off. When any member of the Punk Squad rebelled, they were brutally beaten. Some older members of Synanon balked at this, but they were forced to accept it or be Gamed out of the organization altogether. The shift to violence led to a spate of internal purges within the group. As Dederich’s wife Betty wrote, “We’re beginning to find some creeps amongst the squares.”

The question of children at Synanon had been troubling Dederich even before the Punk Squad arrived. It had been usual for children born to families at Synanon to be separated from their parents and raised by the community as a whole. But Dederich now began to wonder whether this was too much effort. In a speech he gave on the Wire, an FM radio station he had installed at the Badger complex, he announced, “There’s no profit to this community in raising our own children … every baby that we indulge a Synanon female with takes up a bed and somewhere between $100,000 and $200,000 worth of energy.” To those who claimed they wanted to have a baby, he explained the experience was greatly overrated: “I understand it’s more like crapping a football than anything else.” It wasn’t long before Dederich came up with a practicable solution: all male members would receive vasectomies. Pregnant females were ordered to have abortions.

Some agreed immediately, rushing to Synanon’s hospital. Others needed to be Gamed into it. Regarding the baby ban, Dederich opined, “Nothing is sacred just because it’s been done for a million years.” Curiously enough, only Dederich himself failed to receive the snip, but then he was having his own problems. In April 1977, Betty died and Dederich found himself alone. He immediately announced that he would accept applications from any women who wanted to marry him. Six applied and he eventually chose a thirty-one-year old. He was so delighted with the experiment that he ordered all married couples to take separation vows and pick a new mate every three years.

Even with the sterilizations and the decimation of the family unit, Synanon continued to have trouble with its youngest members. Encouraged to play the Game from the age of four, many children chose to run away from the constant verbal and physical abuse. Farmers who lived on ranches near the Badger complex would often be awakened in the middle of the night by sobbing runaways seeking help. Nevertheless, locals’ accusations of child abuse and kidnapping failed to cause Dederich much anxiety, largely because the sheriff was firmly in his pocket, and both his deputies were loyal Synanon members.

This sense of security notwithstanding, a doomsday philosophy was growing within Synanon. Dederich was increasingly espousing a “we–they” philosophy with the outside world, and his paranoia was infusing the group. Brawls over alleged slights were increasingly common between members and locals, leading Dederich to create a specially trained force to protect Synanon’s people and property. He termed them the “Imperial Marines” and watched on with glee as they practiced a special form of karate they had named “Syno-do.” But the Imperial Marines were only the tip of the iceberg. When you saw Synanon’s residents standing in line in their uniform of dungarees, with their clipped hair, you saw less a utopian community than an angry militia. This comparison was made even stronger when it was revealed that Synanon had bought over $300,000 worth of guns and ammunition.

Despite Synanon’s intimidating stature, a few sought to shed light on its abuses. Paul Morantz, a crusading Los Angeles attorney, had sought to free members whose families believed had been kept against their will. In September 1977, he won a $300,000 judgment against Synanon for abducting and brainwashing a member. The news sent Dederich into a rage. Soon afterwards, he spoke on the Wire, announcing the organization’s “New Religious Posture.”

“We’re not going to mess with the old-time, turn-the-other-cheek religious postures. Our religious posture is: Don’t mess with us—you can get killed dead, literally dead! ... I am quite willing to break some lawyer’s legs and next break his wife’s legs and threaten to cut their child’s arm off. That is the end of that lawyer. That is a very satisfactory, humane way of transmitting information. … I really do want an ear in a glass of alcohol on my desk. Yes indeed.” The next month Paul Morantz was bitten on the hand by a four-and-a-half-foot-long rattlesnake that had been placed in his mailbox. He barely survived. Two members of the Imperial Marines were accused of conspiracy to commit murder.

However, thanks to the work of Morantz and that of the tiny local newspaper, The Point Reyes Light, the wider world started to take notice. It was not an easy task though. When Time magazine and NBC ran critical profiles on Synanon, their executives were bombarded with death threats. A former board director of the group who spoke out against Dederich found his guard dog hanged outside his house. Another former member who wanted to visit one of the Synanon complexes was tied to a post and pistol-whipped for being a “splittee.” Tension was building, it seemed an explosion of extreme violence could happen at any time, and then on 17 November 1978, over nine hundred people were killed and an American congressman assassinated in what became known as the Jonestown Massacre in Guyana. Suddenly, the authorities could no longer look the other way at what, in the cold light of day, was undoubtedly a cult. Within days, Synanon was raided by the police. Incriminating material was found, including a recording of Dederich’s “New Religious Posture.” Dederich himself was nowhere to be found, although he was later tracked down to a Synanon property in Arizona. When over thirty police officers burst into the house, they found the sixty-five-year-old Dederich sitting by himself in a stupor. In front of him was an empty bottle of whiskey.

See press about “Shaved Heads, Snipped Tubes, Imperial Marines, and Dope Fiends” on The New Yorker's “Page-turner” blog, longform.org, and therumpus.net.

Bibliography

Barbara Leslie Austin, Sad Nun at Synanon (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1970).

Daniel Casriel, So Fair a House: The Story of Synanon (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1963).

Betty Dederich, No Time for “Yeah But” (Marshall, CA: Synanon, 1978).

S. Guy Endore, Synanon (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968).

Dave Mitchell, Cathy Mitchell, & Richard Ofshe, Light on Synanon: How a Country Weekly Exposed a Corporate Cult—and Won the Pulitzer Prize (New York: Seaview, 1982).

Paul Morantz, Escape: My Lifelong War Against Cults (Los Angeles: Figuroa Press, 2012).

www.paulmorantz.com.

William F. Olin, Escape from Utopia: My Ten Years in Synanon (Santa Cruz, CA: Unity Press, 1980).

Art Pepper & Laurie Pepper, Straight Life: The Story of Art Pepper (New York: Schirmer Books, 1979).

Lewis Yablonsky, The Tunnel Back: Synanon (New York: Macmillan, 1965).

George Pendle is a writer based in Washington, DC. His books include Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons (Harcourt, 2005) and Death: A Life (Three Rivers, 2008). A collection of his essays entitled Happy Failure (An Art Service) will be released later this year.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.