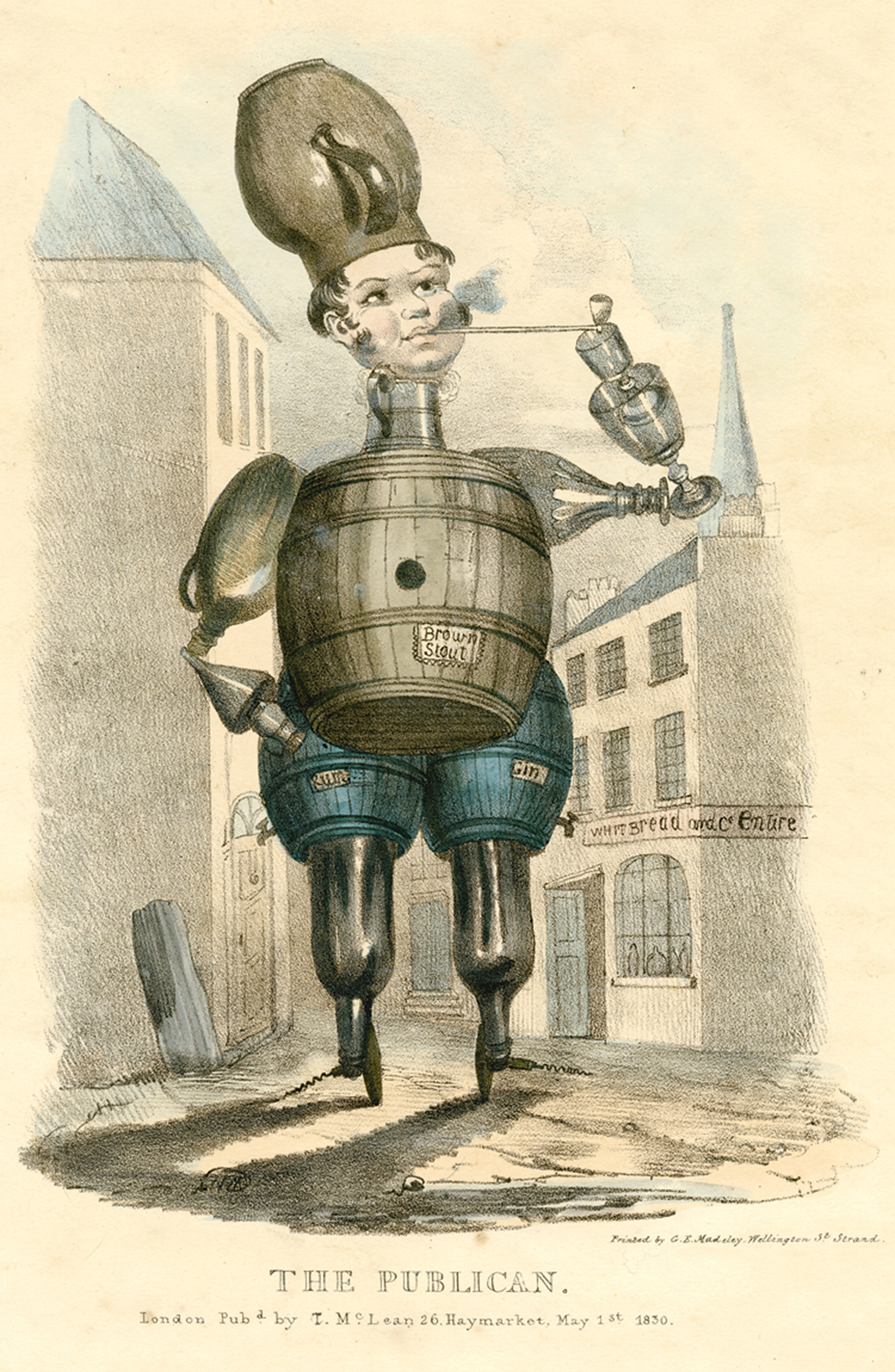

Ingestion / Battling Over Barrels

The fiscal and epistemic politics of beer

William Deringer

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

In February 2013, a group of disgruntled American beer drinkers filed multiple suits in federal court accusing Anheuser-Busch InBev, the world’s largest brewer, of furtively diluting nine of their beers and selling them with an alcohol content 3 to 8% below stated levels.[1] The complaints by erstwhile Bud partisans are a blunt reminder that we are forced to put quite a lot of trust in the drops that fill our tulip glasses and wide-mouth cans. Part of what has made the purported deception so distasteful, if it is true, is that it appears to have been so calculated. The suit claims that the mega-brewers make use of ultra-high-precision alcohol-measuring devices manufactured by the Austrian firm Anton Paar to monitor and then deliberately doctor the booziness of their brews, down to the one-hundredth of a percent.

The brewery has long been a site of deception, though. Perhaps less obviously, it has long been a site of calculation too. And the two—deception and calculation—have often been mashed up together. This was especially true around the turn of the eighteenth century in Britain, when a strange admixture of brewmasters, politicians, mathematicians, and tax collectors became mired in a high-stakes contest over what was going on inside beer barrels. It was a contest that gave rise to modern British beer, to more than a few modern calculations—and, perhaps more indirectly, to the modern British state.

In the late seventeenth century, it was not the drinker that the brewers were trying to deceive. It was the government, or, more precisely, the excise agents who made the rounds between England’s myriad small-scale breweries and assessed taxes on their frothy produce.[2] Ale and beer,[3] dietary staples for the early-modern Englishman, became the object of excise taxes in 1643, during England’s Civil War (along with everything from copper wire to eels used as bait by fisherman). Though formulated as a frantic solution to a wartime fiscal crisis, the taxes on brew became a primary source of nourishment for the unprecedented “military-fiscal” power Britain would assemble in the eighteenth century. For many Britons, the excisemen were the first visible representatives of Britain’s nascent bureaucratic state. Those officers checked in on brewers at mandated times, “gauged” (measured volume) and “tasted” (assessed strength) their produce, and issued the requisite tax bills. The vessels in which beer was produced quickly became sites of contestation, as brewers and excisemen fought bitterly to control the vats and the bitter liquids bubbling inside them.