On Evil: An Interview with Alenka Zupančič

At the conjunction of the impossible and the necessary

Christoph Cox and Alenka Zupančič

Cabinet: In the past several years, we have seen a marked return to “the question of evil” among philosophers and psychoanalytic theorists. Is there something about our particular historical moment that forces us to rethink what “evil” might mean? Or is the question of evil perennial, something repressed that continues to return and assert itself?

Alenka Zupančič: The theoretical necessity of rethinking the concept of evil is linked to the more general interest in the question of ethics. To a considerable extent, this interest is polemical: The way the word “ethics” has been used lately in public discourse is bound to provoke some theoretical and conceptual nausea. It is used either to back up some political or legal decision that nobody is willing to assume fully, or else to keep in check certain developments (in science, for instance) that seem to move much more quickly than our “morals” do. To put it simply, “ethics” is thought of as something strictly restrictive; something that, in the hustle and bustle of our society, marks a place for our intimate fears. In philosophy as well as in psychoanalysis, a conceptual revolt against this notion of ethics took place. The question of evil and its possible definitions arose in reaction to this broader conceptual frame.

The fact that something keeps returning usually means that we are dealing with a conjunction of the impossible and the necessary. Evil seems to be a perfect candidate for such a conjunction. Why is this return happening today? The best I can do to provide a general answer to this question is to point out that the political, economical, and technological events of the recent past have had an important impact on our notion of “the impossible.” The impossible has, so to speak, lost its rights. On the economic level it seems as if what was once referred to as an economic impossibility (i.e. the limits that a given economic order sets to our projects, as well as to our life in general) is being redefined as some kind of natural impossibility or natural law, (i.e. as something that cannot be changed in any way). The explosion of new technologies inspires something that one could call a “desperate optimism.” On this level, it seems that almost everything is possible, but in a way that makes us feel that none of these possibilities contains what Lacan calls a Real, an “absolute condition” that could catch and sustain our desire for more than just a passing moment. On the political level, the fall of Communism has made western democracies lose sight of their own contradictions and all alternatives are declared impossible. So, if we consider all this, what you call the return of the question of evil might be a way for the impossible to remind us that we have not yet done away with its necessity.

The philosophical category of evil can also introduce some distance and reflection into what is—and always has been—an inherent bond between evil and the Imaginary. Evil has always been an object of fascination, with all the ambiguity and ambivalence that characterize the latter. Fascination could be said to be the aesthetic feeling of the state of contradiction. It implies, at the same time, attraction and repulsion. “evil” is not only something that we abhor more than anything else; it is also something that manages to catch hold of our desire. One could even say that the thing that makes a certain object or phenomenon “evil” is precisely the fact that it gives body to this ambiguity of desire and abhorrence. The link between “evil” (in the common use of this word) and the Imaginary springs from the fact that we are dealing precisely with something that has no image. This is not as paradoxical as it might sound. Strictly speaking—and here I am drawing more on Lacanian psychoanalysis than on philosophy—the Imaginary register is in itself a response to the lack of the Image. The more this lack or absence is burdensome, the more frenetic is the production of images. But also (and here we come back to the question of evil), the more closely an image gets to occupy the very place of the lack of the Image, the greater will be its power of fascination.

Within reality as it is constituted via what Lacan calls the Imaginary and the Symbolic mechanisms, there is a “place of the lack of the Image,” which is symbolically designated as such. That is to say that the very mechanism of representation posits its own limits and designates a certain beyond which it refers to as “unrepresentable.” In this case, we can say that the place of something that has no image is designated symbolically; and it is this very designation that endows whatever finds itself in this place with the special power of fascination. Since this unrepresentable is usually associated with the transgression of the given limits of the Symbolic, it is spontaneously perceived as “evil,” or at least as disturbing. Let us take an example: When it comes to the stories that play upon a neat distinction between “good” and “evil” and their conflict, we are not only more fascinated by “evil” characters; it is also clear that the force of the story depends on the strength of the “evil” character. Why is this so? The usual answer is that the “good” is always somehow flat, whereas “evil” displays an intriguing complexity. But what exactly is this complexity about? It is certainly not about some deeper motives or reasons for this “evil” being “evil.” The moment we get any kind of psychological or other explanation for why somebody is “evil,” the spell is broken, so to speak. The complexity and depth of “evil” characters are related to the fact that they seem to have no other reason for doing what they are doing but the fun (or spite) of it. In this sense, they are as “flat” as can be. But at the same time, this lack of depth can itself become something palpable, a most oppressive and massive presence. In these stories, as well as in what constitutes the individual or the collective Imaginary, evil is usually precisely this: that which lends its “face” to some disturbing void “beyond representation.”

The important point to remember here is that this “void” is structural and not empirical. It is not some empty space or no man’s land that could be gradually reduced to nothing or conquered by the advance of knowledge and science. The fact that science itself can function as the embodiment or the agent of evil is significant enough in this regard. Take the recent example of Dolly, or of cloning in general. It is clear that here we are dealing with a striking transgression of the limits of our Symbolic universe. In this example, we can also grasp what makes the difference between image and Image. Dolly looks like any other sheep; her “image” is just like the image of any other sheep. And yet, her place in the Symbolic, or rather, the fact that there is no established place for such a being in the given Symbolic order, endows her image with a special “glow.”

So, the first important thing that the philosophical (as well as psychoanalytical) perspective can bring to the question of evil is thus to establish and maintain the difference between this void, which is an effect of structure, and the images that come to represent or embody it. Not to confound the two is the first step in any analysis of phenomena that are referred to as “evil.”

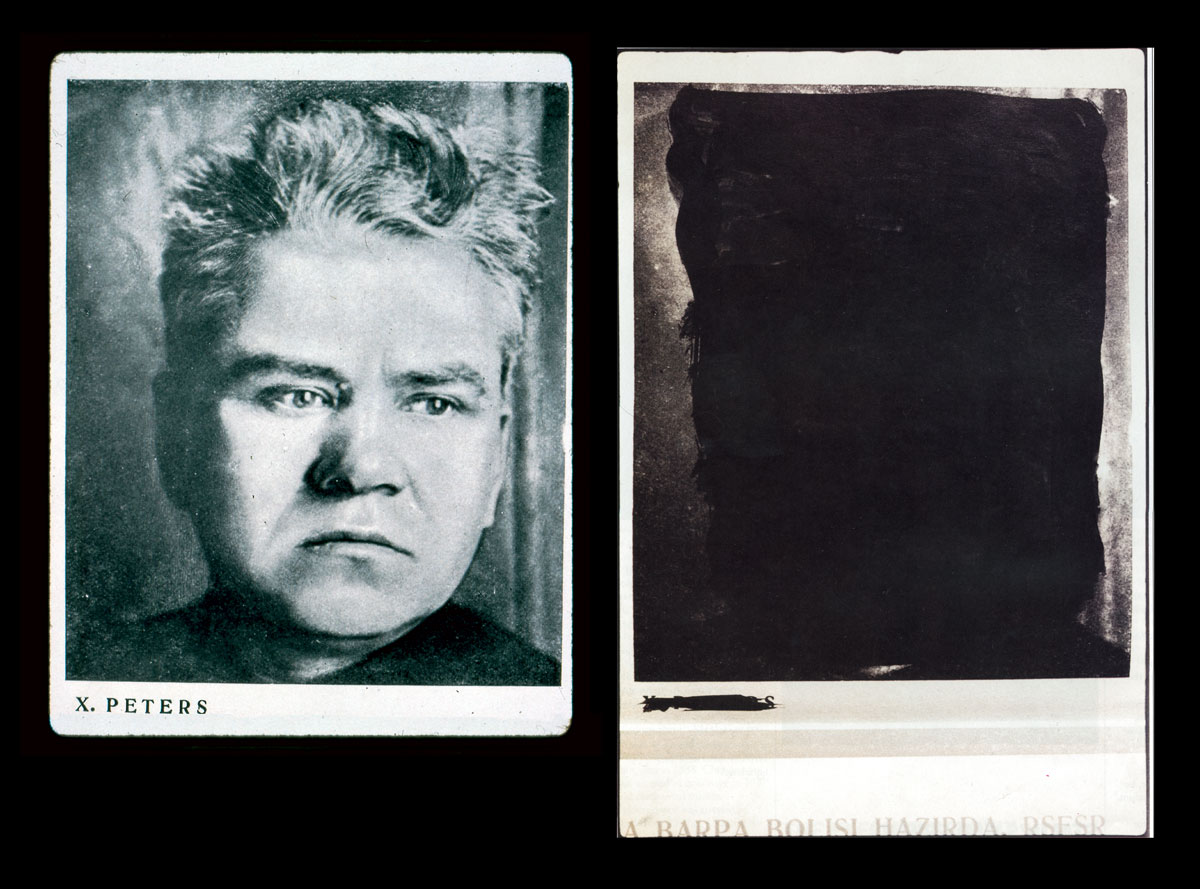

I’m interested in the idea that “evil has no image.” In our reservoir of images, is there an adequate image of evil? Is there an image of evil that “occupies the very place of the lack of the Image”? Those images that spring to mind (monsters, the face of Hitler, representations of the devil) always seem somehow inadequate.

Let’s start with Hitler. It is probably no coincidence that the two best movies about Hitler are comedies: Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be and Chaplin’s The Great Dictator. The image of Hitler is funny. It is funny because it is so inadequate. In Chaplin’s movie, the image of Hitler is the same as that of the Jewish barber, which is precisely the point. Images of monsters and devils are inadequate because they try to “illustrate” evil. The point is not that real evil cannot be illustrated or represented, but that we have tendency to call “evil” precisely that which is not represented in a given representation. As to the question of whether there is an image of evil that occupies the very place of the lack of the Image, I would say yes, there is. It is what we could call a “sublime splendor,” “shine,” “glare,” “glow,” or “aura.” It belongs to the Imaginary register, although it is not an image, in the strict sense of the word; rather, it is that which makes a certain image “shine” and stand out. You could say that it is an effect of the Real on our imagination, the last veil or “screen” that separates us from the impossible Real.

In To Be or Not To Be, Lubitsch provides a very good example of “the image that occupies the very place of the lack of the Image.” At the beginning of the film, there is a brilliant scene in which a group of actors is rehearsing a play that features Hitler. The director is complaining about the appearance of the actor who plays Hitler, saying that his make-up is bad and that he doesn’t look like Hitler at all. He also says that what he sees in front of him is just an ordinary man. The scene continues, and the director is trying desperately to name the mysterious “something more” that distinguishes the appearance of Hitler from the appearance of the actor in front of him. One could say that he is trying to name the “evil” that distinguishes Hitler from this man who actually looks a lot like Hitler. He is searching and searching, and finally he notices a photograph of Hitler on the wall, and triumphantly cries out: “That’s it! This is what Hitler looks like!” “But sir,” replies the actor, “this picture was taken of me.” Needless to say, we as spectators were very much taken in by the enthusiasm of the director who saw in the picture something quite different from this poor actor. Now, I would say that there is probably no better “image” of the lack of the Image than this “thing” that the director (but also ourselves) has “seen” in the picture on the wall and that made all the difference between the photograph and the actor. One should stress, however, that this phenomenon is not linked exclusively to the question of evil, but to the question of the “unrepresentable” in general.

Why is it that evil captures the imagination but the good does not? Ethics would seem to be bound to the idea that the good is attractive, allied with the beautiful and, as such, something that solicits our desire. But, as you suggest, the opposite is perhaps more plausible. The combination of attraction and repulsion one finds in evil seems, perversely, more attractive to us. What does this tell us about our desire and about the nature of evil and the good?

Here I turn to Kantian ethics, which utterly breaks with the idea that the good is attractive and, as such, can solicit our desire. Kant calls this kind of attraction—this kind of causality—“pathological” or non–ethical. Moreover, Kant rejects the very idea that ethics can be founded on any given notion of the good. In Kantian ethics, we start with an unconditional law that is not founded on any pre-established notion of the good. The singularity of this law lies in the fact that it doesn’t tell us what we must or mustn’t do, but only refers us to the universality that we are ourselves supposed to bring about with our action: “Act only according to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law,” goes the famous formulation of Kant’s categorical imperative. The only definition of “good” in Kantian ethics is that of an action which, firstly, satisfies this demand of the universal and, secondly, has this demand for its only motive. The Kantian notion of the good has no other content. Only an action that is accomplished according to the (moral) law and only because of the law is “good.” If I act out of any other inclination (sympathy, compassion, fear, desire for recognition, etc.), my action cannot be called ethical (or “good”). The uneasiness that this aspect of Kantian theory often provokes springs from the fact that he rejects as “non-ethical” not only egoistic motives but also altruistic ones. Kant doesn’t claim that altruism cannot be genuine or that it always masks some deeper egoism. He simply insists on the fact that ethics is not a question of lower or higher motives, but a question of principles.

Recall that, in Hannah Arendt’s famous example, Nazi functionaries like Eichmann took themselves to be Kantians in this respect: They claimed to act simply on principle without any consideration for the empirical consequences of their actions. In what way is this a perversion of Kant?

This attitude is “perverse” in the strictest clinical meaning of the word: The subject has here assumed the role of a mere instrument of the Will of the Other. In relation to Kant, I would simply stress the following point, which has already been made by Slavoj Zizek: In Kantian ethics, we are responsible for what we refer to as our duty. The moral law is not something that could clear us of all responsibility for our actions; on the contrary, it makes us responsible not only for our actions, but also—and foremost—for the principles that we act upon.

Returning to the question of the good, what is most intriguing in Kant’s conception of ethics is that, strictly speaking, there is no reason (or necessity) for the good being good. The good has no empirical content in which its goodness could be founded. The good is good for itself; it is good because it is good. With this conception, Kant revolutionized the field of ethics. By separating the notion of good from every positive content, preserving it only as something which holds open the space for the unconditional, he accomplished several important things. One that should interest us in this discussion is that he undermined the classical opposition between good and evil. In my reading of Kant, this is related to the fact that the moral law is not something that one could transgress. One can fail to act “according to the principle and only out of the principle”; but this failure cannot be called a transgression. This has some important consequences for the Kantian notion of evil. Let me briefly sketch this notion.

Kant identifies three different modes of “evil.” The first two refer precisely to the fact that we fail to act “according to the (moral) law and only because of the law.” One technical detail that will help us to follow Kant’s argument: Kant calls “legal” those actions that are performed in accordance with the law, and “ethical” those which are also performed only because of the law. Now, if we fail to act “ethically,” this can happen either because we yield to motives that drive us away from the “legal” course of action, or because our course of action, “legal” in itself, is motivated by something other than the (moral) law. An example: Let’s say that someone is trying to make me give a false testimony against someone that he wants to get rid of, and he threatens to hurt me if I refuse. If I give the false testimony because I want to avoid being hurt, this implies the first configuration described above. But it can also happen that I refuse to give the false testimony because, for instance, I fear being punished by God. Which means that I do the right thing for the wrong (Kant would say “pathological”) reasons. My action is “legal,” but it is not “ethical” or “good.” One can see immediately that these two modes of “evil” have little to do with what we usually call “evil.” In these instances, “evil” simply names the fact that the “good” did not take place.

Kant goes on to formulate a third mode of evil, which he calls “radical evil.” A simple way of defining this notion is that it refers to the fact that we give up on the very possibility of the good. That is to say, we give up on the very idea that something other than our inclinations and interests could ever dictate our conduct. Here again, the term “radical evil” does not refer to some empirical content of our actions or to the “quantity of bad” caused by them. In my view, it is completely wrong to relate this Kantian notion to examples such us the Holocaust, mass murders, massacres, and so on. Radical evil is not some most horrible deed; its “radicalness” is linked to the fact that we renounce the possibility of ever acting out of principle. It is radical because it perverts the roots of all possible ethical conduct, and not because it takes the form of some terrible crime. I said before that the principal function of the Kantian notion of the good is to hold open the space for the unconditional or, to use another word, for freedom. Radical evil could be defined as that which closes up this space.

Is your conclusion, then, that our “contemporary ethical ideology” is “radically evil,” insofar as it gives up on the idea of “the impossible,” of anything beyond the empirical?

Precisely. It is noteworthy that in the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), when Kant speaks of “empiricism in morals,” he describes this empiricism with exactly the same words that he later uses to describe “radical evil” (Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone [1793]). A radically evil man is not someone whose only motive is to do “bad things,” or someone who couldn’t care less about the law. It is rather someone who willingly conforms to the law, provided that he can get the slightest benefit out of it. In Kantian theory (which has little to do with what I was speaking about earlier in terms of “the collective or individual Imaginary of evil”) radical evil refers only to two things. It refers, firstly, to the fact that our inclinations are the only determining causes of our actions and, secondly, to the fact that we have consented to our inclinations functioning as the only possible motives of our actions. This consent or decision is, in fact, a matter of principle. But it does not imply that we do “bad things” (in the sense of actions that are not in conformity with the moral law) out of principle. It implies that, on principle, our inclinations are the exclusive criteria upon which we decide the course of our actions. These actions may very well be “legal” in the Kantian sense of the word. They may well be in conformity with the law. There needs to be nothing “horrible” about them.

I should, perhaps, point out that there is yet a fourth notion of evil that Kant speaks about: so-called “diabolical evil.” Within the architectonic of practical reason, diabolical evil is the conceptual counterpart of the supreme good. Kant claims that diabolical evil is conceptually necessary, but empirically impossible. In my view, one should rather say that this notion is conceptually redundant, since, strictly speaking, it implies nothing other than what is already implied in the notion of the supreme good. Here I am, so to speak, going with Kant against Kant. Let me explain. According to Kant, “diabolical evil” would occur if we were to elevate opposition to the moral law to the level of a maxim. In this case the maxim would be opposed to the law not just negatively (as it is in the case of radical evil), but directly. This would imply, for instance, that we would be ready to act contrary to the moral law even if this meant acting contrary to all our inclinations, contrary to our self-interest and to our well-being. We would make it a principle to act against the moral law and we would stick to this principle no matter what (that is, even if it meant our own death).

The difficulty that occurs with this concept of diabolical evil lies in its very definition: Namely, diabolical evil would occur if we elevated opposition to the moral law to the level of a maxim (a principle or a law). What is wrong with this definition? Given the Kantian concept of the moral law—which is not a law that says “do this” or “do that,” but an enigmatic law that only commands us to act in conformity with duty and only because of duty—the following objection arises: If opposition to the moral law were elevated to a maxim or principle, it would no longer be opposition to the moral law; it would be the moral law itself. At this level, no opposition is possible. It is not possible to oppose oneself to the moral law at the level of the (moral) law. Nothing can oppose itself to the moral law on principle (i.e., for non-pathological reasons), without itself becoming a moral law. To act without allowing pathological incentives to influence our actions is to do good. In relation to this definition of the good, (diabolical) evil would then have to be defined as follows: It is evil to oppose oneself, without allowing pathological incentives to influence one’s actions, to actions which do not allow any pathological incentives to influence one’s actions. And this is just absurd.

Earlier, in your discussion of evil and the image, you described “evil” as occupying the space of the impossible. Yet, on your view, “the impossible” is also precisely the space of ethics. What, then, is the relationship between evil and the impossible, evil and ethics?

All along, I have been speaking about evil on two different levels: One is the Kantian theory of evil; the other is the question of what we generally tend to call “evil.” Your question is related to this second level.

I would agree that the space of ethics and the space of “evil” meet around the question of the impossible. However, the “impossible” shouldn’t be understood here simply as something that cannot happen (empirically), although we (as ethical subjects) must never give up on it. I believe that one should reformulate this concept of the impossible, which is predominant in Kant, in terms of what Lacan calls the “Real as impossible.” The point of Lacan’s identification of the Real is not that the real cannot happen. On the contrary, the whole point of the Lacanian concept of the Real is that the impossible happens. This is what could be so traumatic, disturbing, shattering—but also funny—about the Real. The Real happens precisely as the impossible. It is not something that happens when we want it, or try to make it happen, or expect it, or are ready for it. It always happens at the wrong time and in the wrong place. It is always something that doesn’t fit the (established or the anticipated) picture. The Real as impossible means that there is no right time or place for it, and not that it is impossible for it to happen. This notion of the impossible as “the impossible that happens” is the very core of the space of ethics. There is nothing “evil” in the impossible; the question is how we perceive its often shattering effect. The link that you point out between the impossible and evil springs from the fact that we tend to perceive, or to define, the very “impossible that happens” as (automatically) evil. If one takes this identification of evil with the impossible as the definition of evil, then I would in fact be inclined to say, “Long live evil!”

Alenka Zupančič is a leading member of the Lacanian school of philosophers and social theorists in Ljubljana, Slovenia. She edits the book series Analecta and the journal Problemi. She is the author of Ethics of the Real: Kant and Lacan.

Christoph Cox teaches philosophy, critical theory, and contemporary music at Hampshire College. He is a contributing editor at Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.