Antichrist: An Interview with Bernard McGinn

God’s most misunderstood servant

Kristofer Widholm and Bernard McGinn

The Antichrist legend rose out of a sea of Jewish cultural and political turmoil in which the reconstruction and desecration of the Second Temple, rapid post-Alexandrian Hellenization, and harassment by capricious despots gave rise to a form of literature devoted to addressing the needs of a people for whom justice and hope seemed equally remote. These events, and the emerging literary form of apocalyptic eschatology, form a shared background through which Judaism was reshaped and Christianity would eventually be born. Among the innovations of apocalyptic eschatology was the pseudo-prophetic literary device of recasting past or current events as future events—with the difference that in the future recapitulation of these events, God would ultimately vanquish the enemy and reward the faithful. In this projection of the future, current and past oppressors were remodeled as figures of evil-to-come, or “anti-messiahs.” Drawing on these rich sources, it would take the emerging Jesus movement only two centuries to reshape these early formulations into a complex theology of the Antichrist. These theological and imaginative roots, pressed into political and moral service as the Church lived through various permutations of hope, fear, decay, and reform, gave rise to the great menagerie of historical and otherworldly figures thought to be the Antichrist. Among them can be counted, to name just a few, Nero, the Roman Empire, various popes, the devil incarnate, the Church itself, and Emperor Frederick II Hohenstaufen.

Bernard McGinn, Professor of Historical Theology and the History of Christianity at the University of Chicago Divinity School, is the author of Antichrist: Two Thousand Years of Human Fascination with Evil. Kristofer Widholm spoke with him over the phone about the historical development of the Antichrist legend and what it might mean to live without it.

Cabinet: Why did the Antichrist legend develop? Is Satan, who after all predates the Antichrist figure, somehow inadequate?

Bernard McGinn: The figure of the Antichrist in the fullest sense is found only within Christianity. There are anti-messiahs in some of the Second Temple (500 BCE–50 CE) Jewish texts, and I think that is important for understanding how the legend of the Antichrist arose. But it is only within the context of Christian belief, where Jesus is not only the messiah, but also God come to earth, that the Antichrist figure emerges as the flip side of the coin, so to speak. Just as Christ is the savior and the ideal model for humanity, his last opponent will be a single figure in whom all evil becomes concentrated.

When the apocalyptic view was taken over by the Jews and gentiles who accepted Jesus of Nazareth, the stark opposition between good and evil that is essential to apocalypticism helped fashion the Antichrist legend. This belief in a final, supreme embodiment of evil in human form, someone who would pretend to be Christ himself but who would also finally be defeated by Christ, served to demonstrate the ultimate triumph of Christ in history.[1]

Of course, the relationship between the Antichrist figure and Satan is complicated. There are basically two traditions. In one, Satan will actually become incarnate in the Antichrist, the way God became incarnate in Jesus. This view, however, was rejected by the mainline Christian tradition. In the second, and majority, view, the Antichrist will be a fully human figure whom Satan inhabits in a unique way. Emphasizing the Antichrist as only human is important for showing that Satan’s power is not on the same level with God’s.

You indicate that it was logically necessary for this opposite figure to emerge. Do you see this as a dialectical necessity? What kind of logic are you alluding to?

I’m trying to make theological sense out of historical evidence. The historical evidence indicates that the legend of the Antichrist begins with scattered reflections and materials in the New Testament—a variety of Antichrists, if you will. By the early 2nd century, it is quite clear that Christian faith implies a real “Antichristology,” and by the end of that century, in figures like Hippolytus and Irenaeus, we get the fully developed legend. My argument is a theological one based on asking why this figure emerged in Christianity with a power that anti-messiahs did not have in Judaism or would not have later in Islam, although they exist there. I think that the answer is that Judaism and Islam don’t have a divine messiah figure. Jewish texts refer to the anti-messiah as Armillus (a corruption of Romulus, that is, the leader of Rome seen as the enemy of the Jews). The anti-messiah in Islam is called the Dajjal. I’m not a scholar of Judaism and Islam, but my reading of the literature suggests that neither Armillus nor the Dajjal have the importance in their respective faiths that the Antichrist has had in Christianity.

Is that because these religions have continued to limit themselves, should we say, to historical prognosis, whereas the Christian Antichrist also seems to have developed into an interiorized figure? Part of the Antichrist’s importance seems to be how he also mirrors the principle of evil at work within us.

I think that is an important aspect of the Antichrist’s significance in the history of Christianity. The Antichrist is, indeed, a single figure to come at the end of time, but also the spirit of everyone who opposes Christ, and is therefore multiple and always present. In this aspect of the legend, arising from the Johannine epistles (where the term “Antichrist” first occurs), there is an internalization of the Antichrist that is not found in the Jewish and Islamic traditions. The Antichrist, therefore, is the spirit of religious deception, manifest in every person who says that he or she is a follower of Christ, but who really lives contrary to Christ. When early Christian teachers, like Origen and Augustine, preach on the Antichrist, they don’t deny there will be a final Antichrist, but their basic message is: “Beware lest you are an Antichrist.”

It’s much more of a devotional exercise.

Yes, devotional, but also deeply moral and ethical in terms of asking the question: “Where do you stand? Are you pretending to be a follower of Christ, but within your heart really denying him?” The dread image of the Final Enemy asks believers to look within themselves to see if the spirit of the Antichrist reigns in them. It always has internal as well as external functions. Of course, in some eras and ages, and in certain localities, the external functions were far more important—and far more troubling and dangerous.

Do you see Augustine’s bent towards locating the Antichrist within the self as a result of his being a Neoplatonist, that is, to having a hard time allowing evil to have an existence proper?

I really wouldn’t tie it very much into that. Augustine’s position is complicated. Metaphysically, he argues that evil is not a thing, some kind of a reality. Rather, evil is a lack of a good that should be present. But the lack of a good is a powerful existential fact, and Augustine had a tremendous sense of the power of evil and the deficiency of the human will to do good without divine grace.

You write that apocalyptic literature was part of a developing sense of God’s historical agency, as well as then furthering the development of that sense of divine agency.

Right. That’s part of what makes the study of apocalypticism so fascinating. As I said, apocalypticism is a kind of a mirror that you can hold up to Western society’s religious and cultural traditions to see how they viewed evil. It helps you see how the evil of their times enabled them to project certain understandings of ultimate human evil into the end of times. In that sense, the Antichrist legend demonstrates an oscillation between two modes of viewing final evil: On the one hand, dread of the most savage of persecutors; and on the other, revulsion toward the one who would be the master of religious deception. The antichrist is both the worst of tyrants and the most deceptive of religious fakes. Some eras emphasize the former, others the latter, but both aspects are always present. Seeing concrete historical figures, such as Nero, or some medieval popes as the Antichrist, or at least his predecessor, contributed to aspects of this developing picture.

From time to time the Antichrist figure also seems to represent a movement or group.

This has been one of the very unfortunate sides of apocalyptic traditions in the history of Christianity. Identifying the Antichrist and his adherents with hated “outsiders,” especially Jews and Muslims, or with suspect “insiders” (heretics, etc.), has led to much conflict and persecution.

You seem to indicate, towards the end of the book, that the primary significance or richness of the Antichrist image for us today lies more in our understanding of self than in a specific political or social agenda.

Yes. Of course, the Antichrist legend is still used politically, which shouldn’t surprise us because it has been used politically for almost two millennia now. Taking the Antichrist literally, and therefore politically, was and is erroneous and dangerous, to my mind. The purpose of my book was to argue that we could take the Antichrist seriously as a symbol of evil, especially evil within, without taking the legend in any crude literal sense. Apocalyptic traditions have been the source of much evil and suffering in Western history, but also, paradoxically, of good.

You mean that apocalyptic thinking can provide a sense of hope in the face of seemingly insurmountable evil.

Very much so, as the history of early Christianity and the story of other persecuted groups have shown. It is a very delicate task to tap into the power of apocalyptic symbolism, to resist tyranny without falling into the other side, which is to use these symbols as sources for conflict, hatred, or mania to persecute.

I would assume there has also been, at times, opposition to the Antichrist legend within the Church.

Total denial of the Antichrist was rare before the Enlightenment period in the 18th century. The Enlightenment attempt to do away with the “legendary” aspects of Christianity had a powerful effect on the importance of the Antichrist. Antichrist beliefs did not die out, but there is a sense in which they shifted ground toward cruder and less nuanced theological presentations. Of course, a certain “overkill” in the use of Antichrist rhetoric in the 17th-century religious quarrels also prepared the way for this shift. With so many Christian groups calling each other Antichrist at that time, many people just threw their hands up in despair and decided it was best to abandon this kind of language. Since the Enlightenment, Antichrist beliefs have been strongest within less established forms of Christianity, particularly those we today call Fundamentalist.

You mention the Enlightenment as a factor in the diminished role of the Antichrist. In a review, John J. Reilly, writes: “The problem is not so much that theologians have lost interest in him or that he has ceased to command popular belief. (The first is certainly true, the latter possibly not.) The decline consists in the fact that the artistic possibilities of the figure seem to be exhausted.”[2] Do you think this is a fair assessment?

I think so. One of the things that has happened is that the power of the Antichrist legend remains strong in some circles (especially in Fundamentalism), but it has shifted ground and lost its symbolic significance, as is evident from its role in contemporary art and literature. The picture of the Antichrist found in current Fundamentalist literature, including very popular novels, has been flattened out into a kind of monotony. Things were quite different in the medieval period or the early modern period, which produced great apocalyptic art in which the Antichrist often took a significant role–think of Dante, or Piers Plowman, or Signorelli’s great Antichrist fresco in Orvieto. These are works of genius.

Considering the fragmentation of our sense of community, our ingrained rationalism, and our still lingering modern optimism, will the Antichrist survive?

I think he will survive, though perhaps much diminished. Of course, he is alive and well (if rather boring) for millions of people, among them Fundamentalist Christians who have a pretty powerful sense of the Antichrist. The millions who buy the current Antichrist novels,[3] whether they take them literally or not, testify to the power of the Antichrist legend, even in a rather crude form. There is a kind of fascination with evil, real or fictional. And there have been a few good apocalyptic movies, such as Bergman’s Seventh Seal and Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, which is really an Antichrist story.

Would it be fair to say that one of the problems is that we are not as sophisticated in our understanding of evil as people were before the Enlightenment?

I would tend to agree, although generalizations are always dangerous. People today often tend to look back and think, “Medieval people were ignorant and crude. We are so superior.” Well, anyone who reads medieval literature, studies medieval thought, or admires medieval art and music, will see that the genius of the human spirit was just as active then as it is now, but in different ways. One of the things at the heart of the Enlightenment project was the belief that there is a rational solution to everything—reason can always work it out. In the medieval period they knew better than that. Reason works, and needs to be applied to all sorts of issues, but there are dimensions of human existence, of meaning and history, where reason doesn’t work, where either something above reason, or the symbolic power of images, will help us more than the application of reason.

You indicate in your book that apocalyptic narrative is in some sense a way for a group to communally share a judgment and fate. Apocalyptic literature can become a supplement to our own death, a way of addressing our death together. Do you think that a decline in our sense of community or shared fate has contributed to a lack of interest in apocalyptic thought?

I think that that’s certainly a part of it. On the other hand, we still have communal identities, but they are expressed in different ways. In modern society they tend to be much less religiously oriented and much more centered on the nation-state and its symbols.

If the Antichrist were to disappear, do you see him as leaving behind any clear trace within Western culture—outside of a specifically Christian tradition?

That’s an interesting question. As an historian, I would say yes, because when we look back at the way in which Western culture’s understanding of the nature of evil in both groups and in individuals has developed over the centuries, the Antichrist legend has played an important role. The Antichrist legend is a kind of prism for understanding how evil has been used and understood in Western history. Now the Antichrist has faded in some circles, very dramatically in the last couple of centuries. It is quite possible that by the end of this century the legend will really be dead, but I’m not a prophet.

In your book, the Antichrist is often pictured riding Behemoth and Leviathan, those fearsome beasts described in the book of Job.[4] However, what seems paradoxical about associating these cryptic creatures with the Antichrist—both pictorially and theologically—is that in Job, God exhibits these monsters of chaos as signs of his inscrutable goodness, while for us the Antichrist is undeniably a symbol of pure evil. However, if we were to follow the logic of Job and turn the symbolism of the Antichrist on its head, could we perhaps envision the Antichrist also as one of God’s good creatures—a creature that by supplementing and structuring the apocalyptic moment helps provide evil with meaning?

For Christians, God is the creator of all things, including Satan and the Antichrist. In so far as they are creatures, they come from God, and their being is a being that was given to them by the goodness of the Creator. And in the end the Creator will bring goodness out of evil, even the evil done by the Antichrist. Evil demonstrates the mystery of free will, both in an angelic creature like Satan,[5] and in a human being like the Antichrist. Although Satan and the Antichrist set themselves up against God through the exercise of their freedom, they are part of a divine plan, according to apocalyptic belief. This is crucial to the history of apocalypticism as a way of giving meaning to history, particularly in times when people experienced terrible persecution and fear about what the future was going to bring.

Can there be any meaning to history without an end to it?

We may have a sense of there being some kind of meaning to individual events, but I would agree with those scholars who have claimed that the sense of universal history, at least in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, originated in the apocalyptic imagination. The way in which the ages of world history were sketched out in some of the early apocalypses, the fact that God is seen as in control of the whole of history and that he will give meaning to the ongoing struggle between good and evil at the end—this is essential to apocalypticism. Apocalyptic symbols work through imaginative power, and through an active faith and hope in the meaning of history, even when it seems most without meaning.

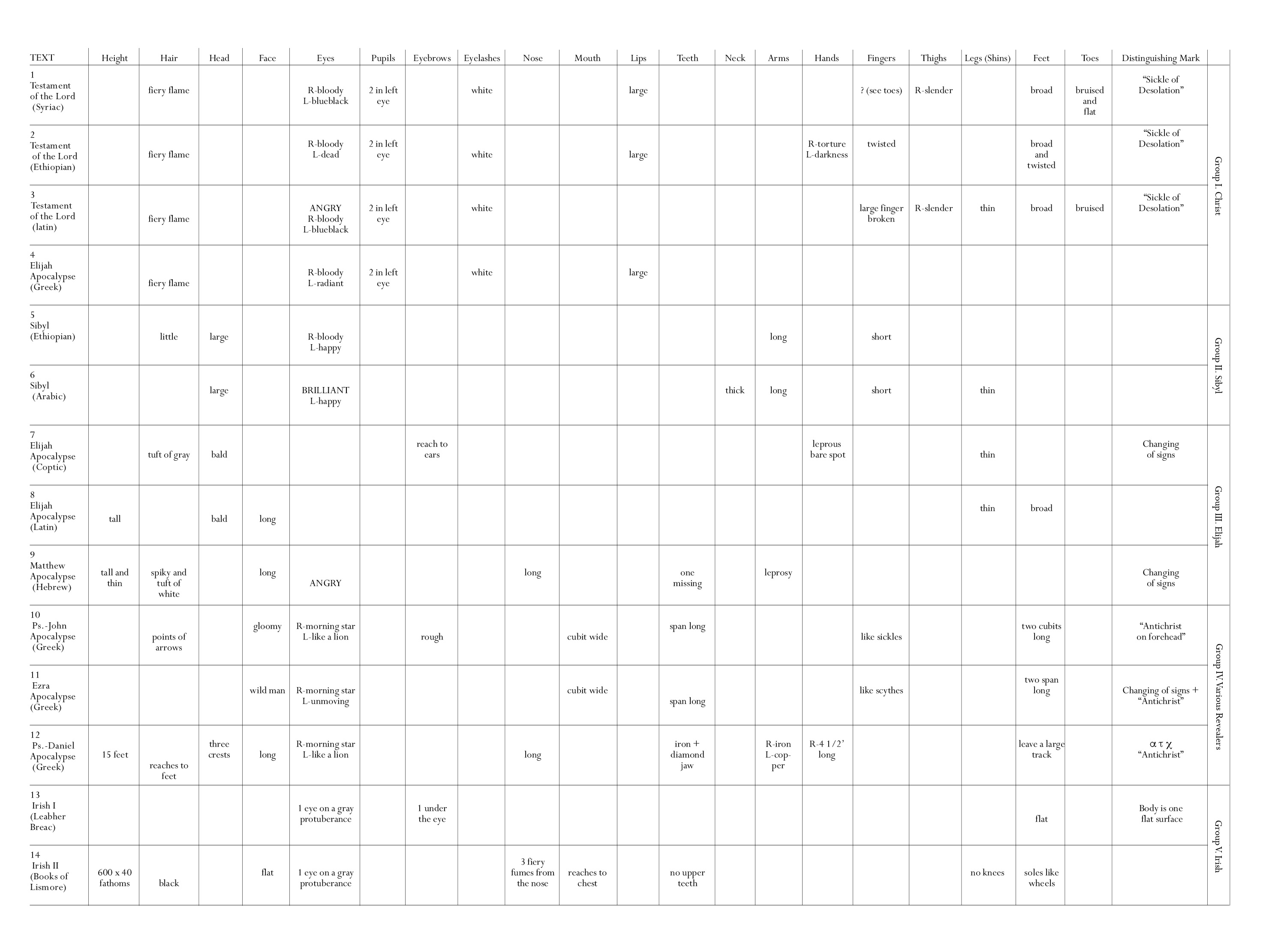

To download a chart of early Antichrist physiognomies, click here. Courtesy Bernard McGinn.

- “For already the secret power of wickedness is at work, secret only for the present until the Restrainer disappears from the scene. And then he will be revealed, that wicked man whom the Lord Jesus will destroy with the breath of his mouth, and annihilate by the radiance of his coming.” New English Bible, Second Thessalonians, 2: 7–8.

- John J. Reilly, review of The End of the Age: A Novel, by Pat Robertson, in Millenial Prophecy Report 4:4. See www.channel1.com/mpr/Articles/44-patrev.html [link defunct—Eds.]

- Examples of these kinds of best-selling works of fiction would be the “Left Behind” series by Tim LaHaye and Jerry Jenkins, the classic The Late Great Planet Earth by Hal Lindsey on which the film Like a Thief in the Night was based, as well as many well-known Christian pop songs such as “I Wish We’d All Been Ready” by Larry Norman.

- Behemoth and Leviathan play a large role not only in the Book of Job, but also throughout the history of Western religion and philosophy. Commonly, Behemoth is thought to be a large land animal, perhaps a hippopotamus, while Leviathan is portrayed as a sea snake. However, the sizes reported in Job for these beasts would place them squarely in the Mesozoic period.

- According to Christian and Judaic belief, Satan was originally chief among the angels.

Bernard McGinn is Naomi Shenstone Donnelley Professor at the Divinity School of the University of Chicago. He has written extensively on the history of apocalypticism and on Christian mysticism.

Kristofer Widholm is a musician and Web developer living in Brooklyn. He

performs with the dork-rock band Morex Optimo, and plays solo as Pharmacy

and Gardens (http://brokenhill.net).