Blown All to Nothing

Explosives, spark, crater

Brian Dillon

The tiny Kentish settlement of Uplees—a few farmhouses, a row of workers’ cottages, little more—lies a dead-flat mile northwest of the village of Oare, which in turn clings to the muddy edge of Faversham, the local market town. Here on the north coast of the county, about fifty miles from London, all is wind-hobbled marshland and sucking acres of tidal silt. The landscape of certain Dickens novels leaches into Joseph Conrad country, an ancient estuarine expanse recalling Roman invasion, medieval industry, prison hulks, and malaria. If you strike out of Faversham across this territory on foot, you can see for miles in all directions: the town’s oddly skeletal church spire behind, the Isle of Sheppey to your right with its road bridge gleaming white, the crosshatching of a container port, two power stations, and a gas storage facility up ahead on the Isle of Grain, which is not an island. Beyond, unseen, is the mouth of the Thames and Conrad’s “immensity of grey tones.” The place feels complexly overwritten with recent infrastructure and deeply sunk in its own past.

From the mid-sixteenth century till the early decades of the twentieth, Faversham and environs were part of the industrial archipelago that produced most of the explosives used by the British military: gunpowder at first, and then a succession of more or less efficient or practicable alternatives. The remains of the earliest powder works in Faversham—the Home Works, built around 1560 in alarming proximity to the town center—may still be seen today in the middle of a quiet housing complex. And in the woods adjacent to Oare, the stabilized ruins of a later factory, most likely dating from the eighteenth century, are dispersed among the canals or leats that once transported raw materials around the site and delivered barrels of finished powder to vessels berthed in Faversham Creek. A decade ago this factory was furnished with wooden walkways and a small heritage center, and most days now there are visiting families and local dog-walkers to be glimpsed among the trees, exploring low brick sheds and staring up at precipitous revetments.

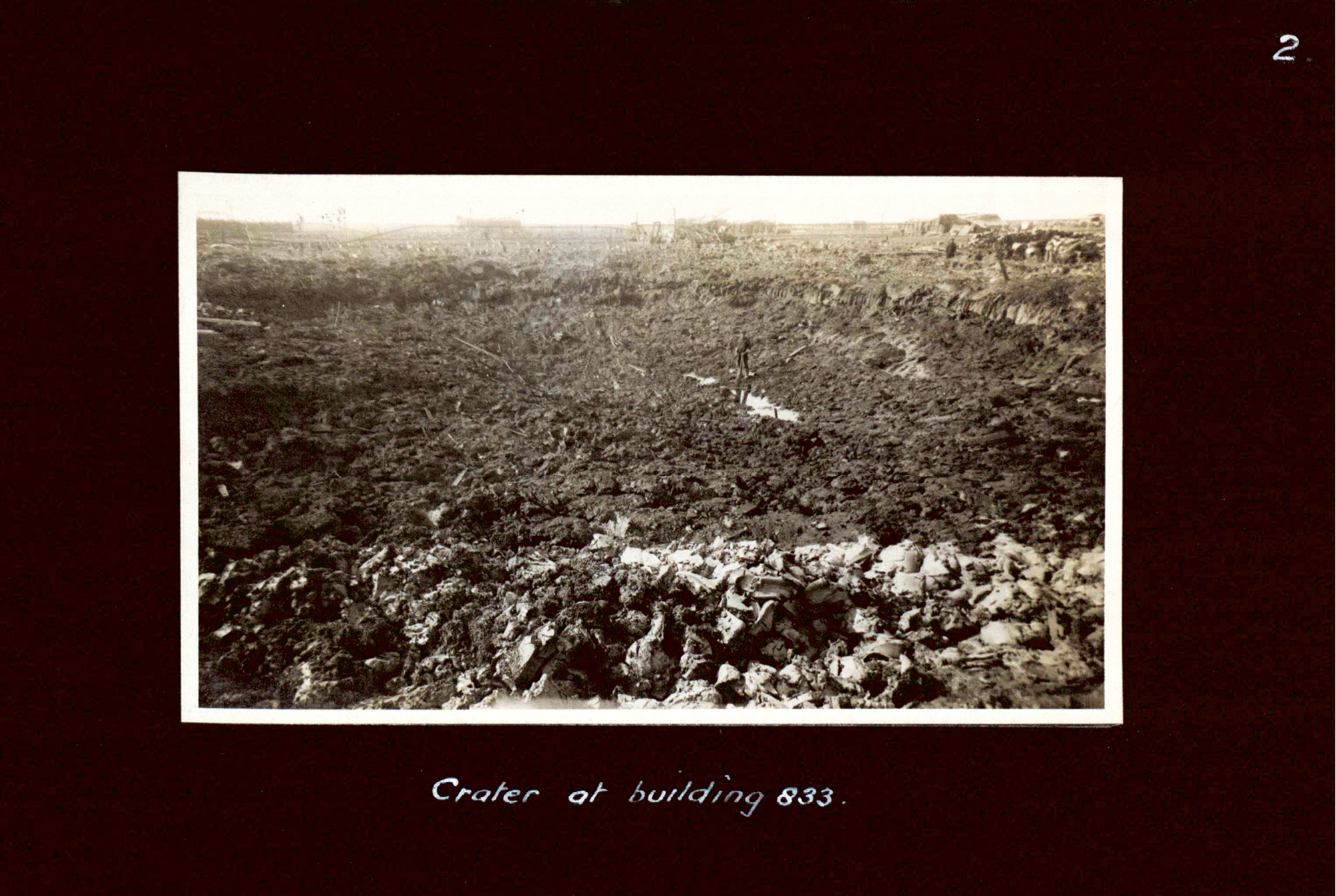

But the most highly developed and substantial portion of Faversham’s explosives industry has so far not been memorialized, in fact has almost vanished, leaving only a pattern of foundations visible from the air and a few ragged concrete stelae, hard to reach among the wide drainage ditches that divide the wetland. The Marsh Works was established in the 1780s on the opposite side of Oare from the wooded factory, and gradually expanded to the west along the Swale, the body of water that separates the Kent coast from Sheppey. In 1847, by agreement with its inventor Christian Schönbein, professor of chemistry at the university in Basel, the Marsh Works became the first plant in the world to produce guncotton, then the most promising alternative to gunpowder. In the summer of that year, an explosion killed twenty-one workers. (In the days following the accident, certain unscrupulous persons along the coast at Whitstable charged locals a few pence to view body parts plucked from surrounding fields.) Manufacture of the new explosive was for the time being abandoned. The complex, however, continued to grow, and in 1873 the Cotton Powder Company (CPC) began producing guncotton again, this time at Uplees.