Leftovers / These Were Once Kings and Queens in Wax

After the fire at Madame Tussaud’s

David Serlin

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

On 20 March 1925, the Manchester Guardian published an account of a massive fire that almost completely destroyed Madame Tussaud’s famous wax museum on Marylebone Road in central London.[1] The fire, which began at 10:30 pm on 19 March, raged through the galleries until early the next morning, despite firefighters’ attempts to contain it. Witnesses to the catastrophe spoke of “red and golden flames” leaping fifty feet into the air as the fire descended deeper into the bowels of the building. According to the Guardian, “the wax models could be distinctly heard sizzling.”

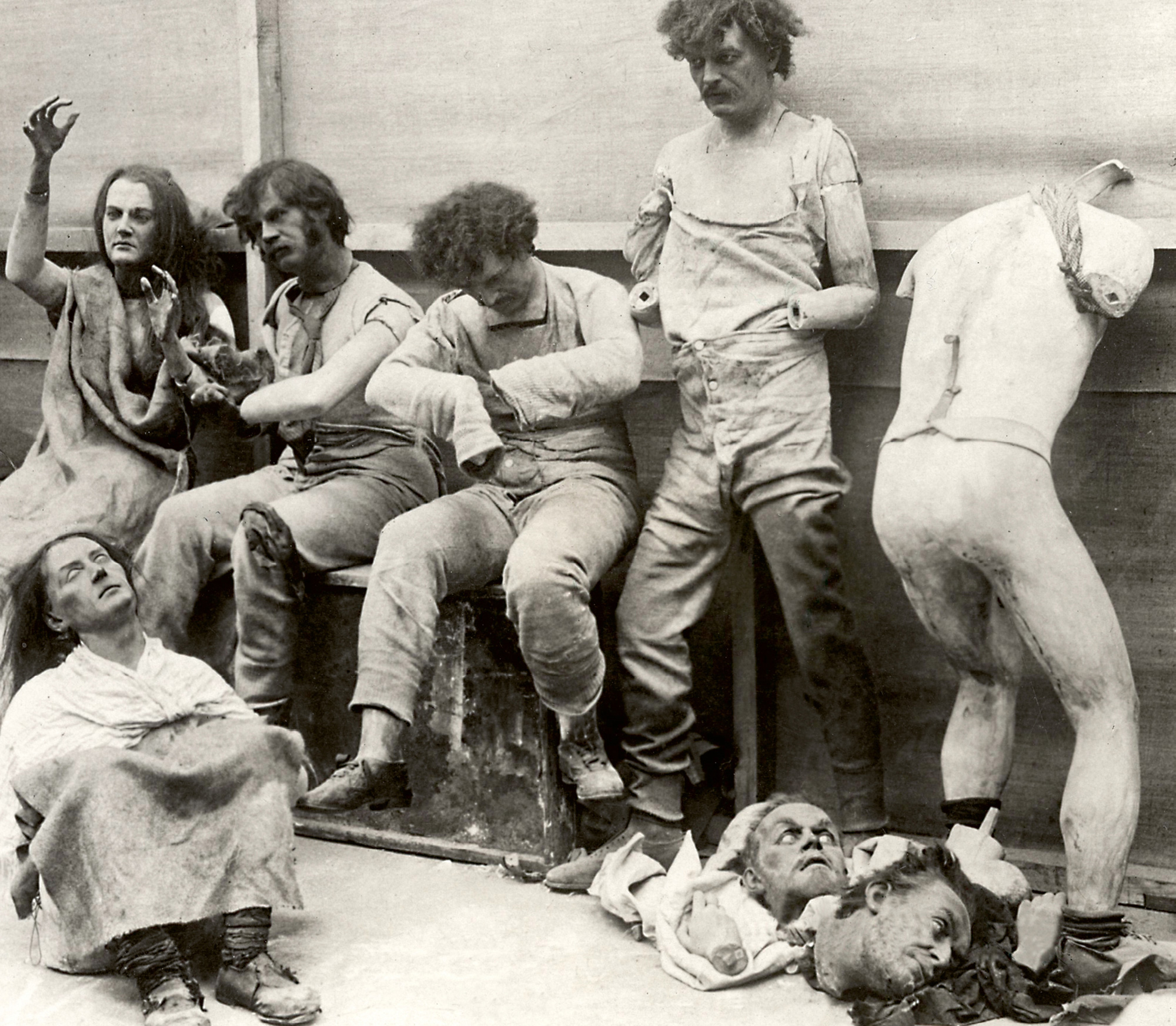

Like the reputation of the museum itself, the fire at Tussaud’s was international news. Het Leven (“Life”), for example, the premier Dutch weekly magazine, ran its news feature about the fire with an image of a small group of wax figures that had been rescued, remarkably, from the flames that had engulfed the building. While the fire at Tussaud’s destroyed as many as four hundred waxworks and countless real-life relics, including a bloodstained shirt worn by Henry IV and a stagecoach used by Napoleon, the photograph depicts a few of the figures that escaped a fiery end, not through any anthropomorphic act of willful survival but through the sheer luck of the draw. Almost nothing in the museum went undamaged: political leaders poised in heroic contemplation found themselves on equal footing with murderers and thieves awaiting judgment for all eternity. The fortunate waxworks in the photograph, however, remained sufficiently unaffected to be propped up, albeit gingerly, against a wall, or seated on a trunk that had apparently been set down for their comfort. Bearing only modest evidence of the previous evening’s conflagration, they resemble nothing so much as inebriated libertines.

The Het Leven image exists as a curiously bright star in a firmament of surviving media that document the dreadful aftermath of that fateful night. A minute-long silent newsreel, for example, distributed by British Pathé four days after the Tussaud fire, breathlessly surveys the basement level as if it were a battlefield, invoking grim memories of the Great War as well as presaging the images of firebombed neighborhoods that Londoners would come to know fifteen years later.[2] In another newsreel, by the Paris-based Gaumont, the material and psychic damage to the museum is conveyed in staccato bursts of corrupted décor—disjointed staircases at broken angles, a shattered glass chandelier, a burned copper dome bleakly revealing open sky—that resemble the gilded detritus scavenged from the wreckage of a doomed ocean liner.[3] A pan across the charred expanse of blackened body parts in a ground floor gallery is preceded by the caption, “THESE WERE ONCE KINGS AND QUEENS—IN WAX.”