Buster Keaton’s Cure

The long twilight of a silent star

Charlie Fox

“Now, ladies and gentlemen, I have really something of great interest to the public!” The former vaudevillian Ed Wynn is providing the introductory patter to a segment in an episode of his eponymous comedy show, broadcast live in primetime on 9 December 1949. Wynn, who would later voice the Mad Hatter in Disney’s adaptation of Alice In Wonderland (1951), is a jolly host: he looks like a horned owl in a clown costume, plump and bespectacled with a rubbery excitement to his expressions that suggests he’s already half-cartoon. His speech has an avuncular warmth, tumbling with a ringmaster’s glee through his slightly pinched sinuses. The other treats on the show have included a special guest appearance from the famously deadpan actress Virginia O’Brien, nicknamed “Miss Ice Glacier,” who sang “Bird in a Gilded Cage,” and blubbery Ed’s attempt to dance a ballet overture. The curtains behind Wynn that hide the set from the audience are fuzzy, gray, and monstrously thick, looking like nothing so much as a carefully graded spectrum of various sorts of domestic dust; the studio has the acoustics of a damp attic. Wynn tells the audience that they are about to have “the great privilege in seeing for the first time, certainly on television, and alive, almost!”—an odd thing to say, don’t you think?—“one of the greatest of the great comedians of the silent moving-picture days. Mr. Buster Keaton!”

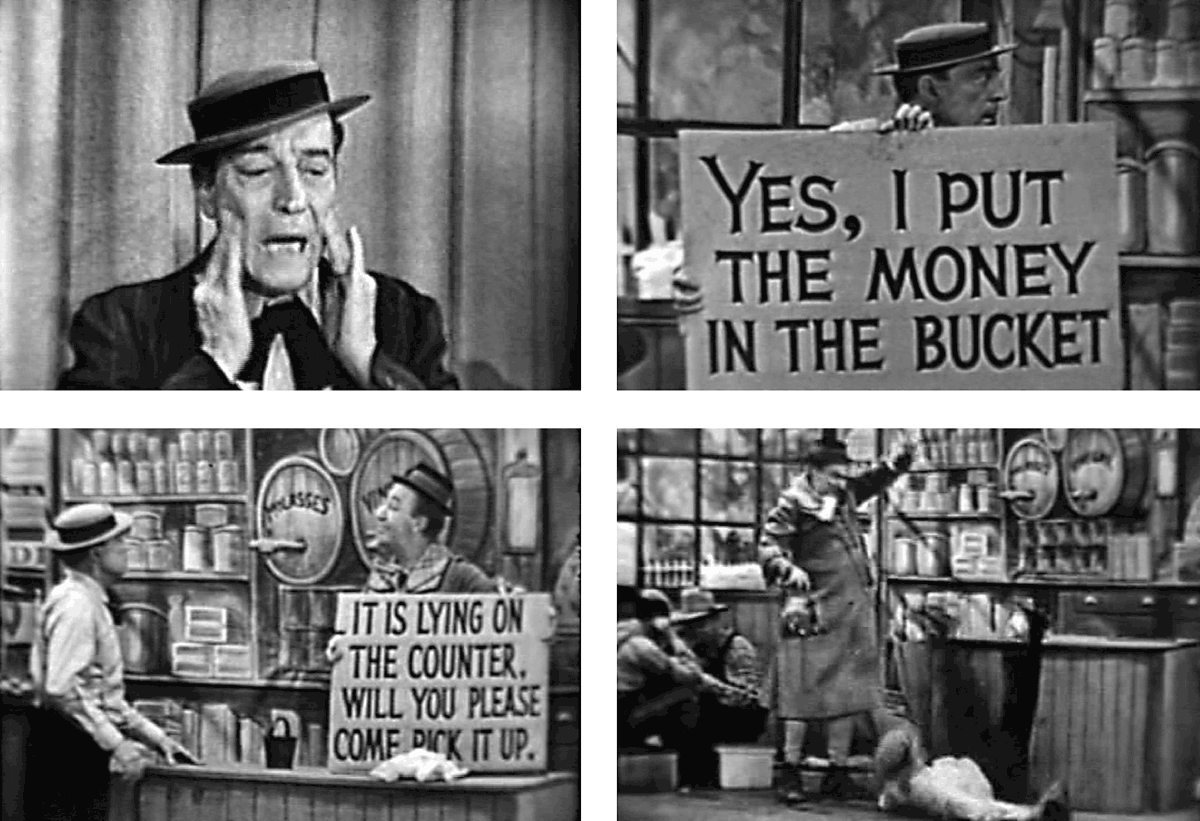

Here he is, a little man in his trademark outfit of porkpie hat and rumpled suit. He ignores all conversational prompts, playing dumb and nodding a little as if out of beat with the situation, mid-daydream. “The American public would like to hear you say something. Would you say something? Go ahead,” Wynn cajoles him, “speak!” And upon these ventriloquist’s orders, Buster commences a routine that looks like a ludic premonition of the anguished choreographies found in Samuel Beckett’s plays. (Shortly before his death, he would appear as the solitary figure in Beckett’s metaphysically queasy 1965 short, Film).[1] Carefully, the voice must be readied—the whole body is involved. He shrugs his shoulders a few times, bends his knees to ensure that he’s suitably limber, then performs some exaggerated respirations that make his chest swell and deflate like a ragged bellows. There’s a mysterious procedure of cheek massage and jaw agitation in which he looks like a gargoyle attempting to reverse the effects of amphetamines. He spritzes something into his mouth, the host looks quizzically on, and what shy laughter there was in the audience has receded like a weak breeze. Then, at last, he says “Hello!” in an eager innocent’s yelp. Wynn is astonished! His owlish eyes go wide, and Buster falls, exhausted, into his arms as the audience chuckles. Television is probably more accommodating to such outbursts of staccato weirdness than any other medium, but Buster’s act is much more than just an odd trick. He isn’t out of shape: a subsequent re-enactment of “the first scene he ever did for a camera” will prove he’s freakishly limber for a fifty-four-year-old and his timing’s still pin-sharp. This impish revision of an old routine about a hatful of black molasses, with Wynn taking the role originally played by Buster’s old pal (and Hollywood outcast) Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle will exaggerate the formal habits of silent film—intertitles and melodramatic expressions—to levels of inspired lunacy. Like in all his best films, the sleepwalking smoothness of his physical antics combines with a preternatural sense of how film itself can be the subject of witty subversions and knowing mischief.

That bewildering joke, which suggests that Buster can only speak after laboriously readying his body, plays on the strange fate of silent film stars in our imagination: silence is a symptom of their magical condition. The more of them you watch, the more difficult it becomes to think of them as possessing voices at all. (Would Theda Bara be mute in public, too?) What breeds in silence is, naturally, a sort of excitable noise: heightened fascination, fantastical lore, and outlandish forms of erotic gossip, all of which conspire to hide the dumbstruck star. The uproarious arrival of sound often led these delicate figures into the long and lonely twilight of their careers. The silence that reigned in the cinema twenty years before seemed unspeakably distant and, like the others, Buster had transformed into a relic, an object suitable for gawking audiences and inducing occasionally lyrical fits of nostalgic reflection. But he was able to stage a return when many had retreated into memory or private darkness. The year of his appearance on The Ed Wynn Show, Clara Bow, the actress who had slinked through the world’s erotic dreamscape for much of the 1920s, had been admitted to a mental hospital with a mistaken diagnosis of schizophrenia, then subjected to aggressive electroshock treatment. Ravaged upon release, she abandoned her family and moved into a bungalow near Los Angeles that she seldom left until her death in 1965. Buster was ruined by a slow fall into alcoholism but returned, and yet his rehabilitation and—let’s go for the hysterical mood of melodrama—resurrection conjure up more ghosts. His alcoholism was seemingly cured by a manic, spuriously medical process, and he didn’t quite vanish in the obscure years before its success. There’s plenty of intoxicating material to be found by studying Buster if you dodge the lustrous peaks of his career in favor of going deep into its gloom and supposed dead ends.

Unfurling this distended postscript without acknowledgement of the astonishing properties of Buster’s art would be unkind. A case study of his childhood might be equally rich, too. Born in 1895, which makes his age exactly synchronous with cinema itself, he was a willing participant in vaudevillian mishegoss as soon as he could walk. According to myths circulated by his father, he had survived a few twirls in the eye of a Kansas tornado when he was three. Alongside his parents, he was part of the Three Keatons, a riotous slapstick act in which his mother played saxophone and his father discoursed on child discipline while hurling Buster about the stage. His education was irregular; his father was an alcoholic. In photographs from this time, he looks like a playful wraith.

As a child, silent cinema was a ghost house I had to explore. My sense of reality was already perilously vague and the thought of these films that would allow me to watch the mischief of specters—everyone in them was, by the time of my childhood, decidedly dead—was a deep and wicked thrill. Whole days disappeared in the attempt to cast the shadow of Nosferatu on the wall as I climbed the stairs again and again. (I failed: it was very tough to get the head correct, my skull lacking the required Expressionist jags.) I remember chancing across Buster’s face in a film history book one monochrome morning and feeling the peculiar sensation that this haunted boy knew I was looking at him. Wholly at odds with the wild-eyed mania that silent film acting often promised, his presence was gentle and radiated an unmistakable sadness. He had the dreamy, lonesome look of a stray dog. His eyes would widen in moments of moonstruck goofing or genuine enchantment, then look on the edge of sleep when he was puzzled. Nobody else’s body yielded so smoothly to the sublime mindlessness that the best physical comedy requires, and he was beautiful in a way that, say, a clerical nebbish like Harold Lloyd would never match. On film, even in flashes of jackrabbit energy, he’s airily nimble and weirdly aided by the jittery accelerations and diminuendos of silent film speed that can make him seem too limber in his skittering or too light in his falls to be made of flesh and bone. At those moments he’s closer to a bewitched marionette.

In 1928, Buster was talked into giving up his own studio, where he made his finest films, and switching to the ascendant MGM. Bad contracts were signed; dark clouds began to settle in his head. His subsequent drift into alcoholism looks like a commonplace response to the baleful state of Hollywood and deep marital discord. Seven years before, Buster had married Natalie Talmadge, a delicate, fawn-like beauty of seemingly untrammelled malevolence who banished him from their bedroom once he had supplied her with the two sons (and the mansion) she required, reported him for kidnapping when he took the boys for a weekend jaunt, and refused to hear his name in her presence until she died in 1969 after years blasted on painkillers and hopelessly soaked in booze. She appears to have dreamed of transforming Buster into a bland mixture of benefactor and milquetoast, though let’s note that as the far less successful middle sister of two wildly famous actresses, Norma and Constance, she was never able to tell her own story, skewed and vituperative as it might have been. Natalie’s chief occupation was perfecting the girlish swirls of her sisters’ signatures on an endless cascade of publicity stills. In a photograph taken on their wedding day, Buster stands in between the three sisters in a spotlight of May sunshine, looking like a man about to be led to the gallows. Norma and Constance retired with the advent of the talkies. Norma was reputedly the inspiration for Lina Lamont in Singin’ in the Rain (1952), the starlet of uncommon radiance destroyed by the arrival of sound, which reveals to the world that she’s in possession of the shrill, needling voice of a Brooklyn chipmunk. The reclusive, gone-to-ruin silent movie heroine played by Gloria Swanson in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950) is also an acidulous portrait of Norma. Like her sister, she suffered an unhappy fate, fleeing to Las Vegas, gorging on painkillers, seeing no one, and drinking all the time until she died there on Christmas Eve in 1957. (Much the same happened to Constance: they made a tragic trio).

As the marriage dissolved, Buster tumbled toward oblivion, too, succumbing to the song of what he called his “inner Bacchus” in order to escape domestic pressures. He became estranged from his sons, whose last names were changed so that they were suddenly Talmadge property. The pleasures of drinking had long since faded into the delirious routine of everyday alcoholism as he got drunk from sunrise until he blacked out. As he recalls in his autobiography, My Wonderful World of Slapstick (1960), “all my weekends were lost weekends.”[2] He left the mansion and drifted around Hollywood in a land yacht, “a fancy house on wheels that had twin motors in the chassis of a Fifth Avenue bus, contained two drawing rooms, a galley, an observation deck and slept eight persons.” By way of melancholy endorsement, he notes, “I had as much fun with my land yacht as a man can whose purpose is to forget his whole private world has fallen apart.” In a drunken blur one Monday afternoon, he staggered down to the MGM lot and befriended an extra—“I could not say today whether she was a blonde, brunette or a redhead”—took her home, and let her have her pick of the contents of Natalie’s enormous wardrobe, heaping up piles of cocktail dresses, fur coats, gowns, and sparkling shoes. He appeared in What? No Beer! (1933), a dismal but hugely successful talkie with the antic Jimmy Durante in which this mismatched double act accidentally become beer barons as Prohibition’s on the wane. Buster plays a taxidermist and suitably moves with the shambling gait of a bear half-stuffed with wool. When shooting was over one night, he tried to drink himself into unconsciousness but failed and came reeling into the studio the next morning, only to promptly pass out.

When he awoke, he found a letter from the studio bosses telling him he was fired. Buster had become a drunk at a time when alcohol was a source of immense moral panic. (William Burroughs’s grandmother had the motto, “I’d rather a son o’ mine came home dead than drunk!”) Grimmest of all, he had fallen for whiskey, which, as he said later, was popularly regarded as “pure evil, apparently being distilled in hell itself.”

Throughout the early 1930s, the backdrops shuffled like a collection of old postcards as Buster appeared in cheap slapstick short films shot in Mexico, France, and England. He read the “idiot cards” that rendered lines in foreign languages into phonetic English, repeating his dialogue over and over again for different territories to save on the expense of dubbing. Drinking was a useless form of self-sabotage—even knockout drunk, he was still able to perform his stunts.

Whenever he sobered up, he was stricken with delirium tremens. In the nightmarish hallucinations that typically accompany this condition, he was attacked by bloodthirsty squirrels. According to rumor, he escaped from his straitjacket while in a psychiatric hospital, performing the great trick he had learned from Harry Houdini as a boy. In 1933, somebody sent him to dry out in the seclusion of Arrowhead Springs in San Bernardino, a nurse called Mae Scriven in tow to supply “the right amounts of whiskey so I wouldn’t go nuts and hypodermics to put me to sleep.” After a week of enforced temperance, he absconded to Mexico and married Scriven in accordance with some drunken, japing impulse. (Marrying your nurse must always be a sign of full-scale psychoanalytic catastrophe.) They soon divorced.

The screwball humor that came in the dust of the Depression and after the end of silent cinema often revels irrepressibly in the sound of speech itself: puns, comic accents, wolf whistles, sly one-liners, devilish loquacity, seductions sung with tongue in cheek, anarchic contortions of flirtatious, professorial, and gangster talk. You can find all of this friskily embodied in the verbal shenanigans of Groucho Marx and even in the to-and-fro routines of lesser lights like Abbott and Costello. Against that, Buster’s humor can look glassy, slow, and luminously strange, like ballet.

Dreaming of Buster’s voice is a natural activity. Some peculiar flutter in the mind always makes you lend voices to silent things. A sudden pall of sadness is perhaps natural, too, on hearing it for the first time, as he doesn’t produce the angelic mumble you might imagine but the parched groan of something that lives in the dark. In a high-spirited moment from Doughboys (1930), he sings and plays ukulele with two other soldiers before lights out, providing a basso punctuation of rhythmic gibberish while one of his pals takes the lead with an utterly bewildering and ecstatic outburst of half-drowned scat singing that suggests the yowling of a hungry cat.

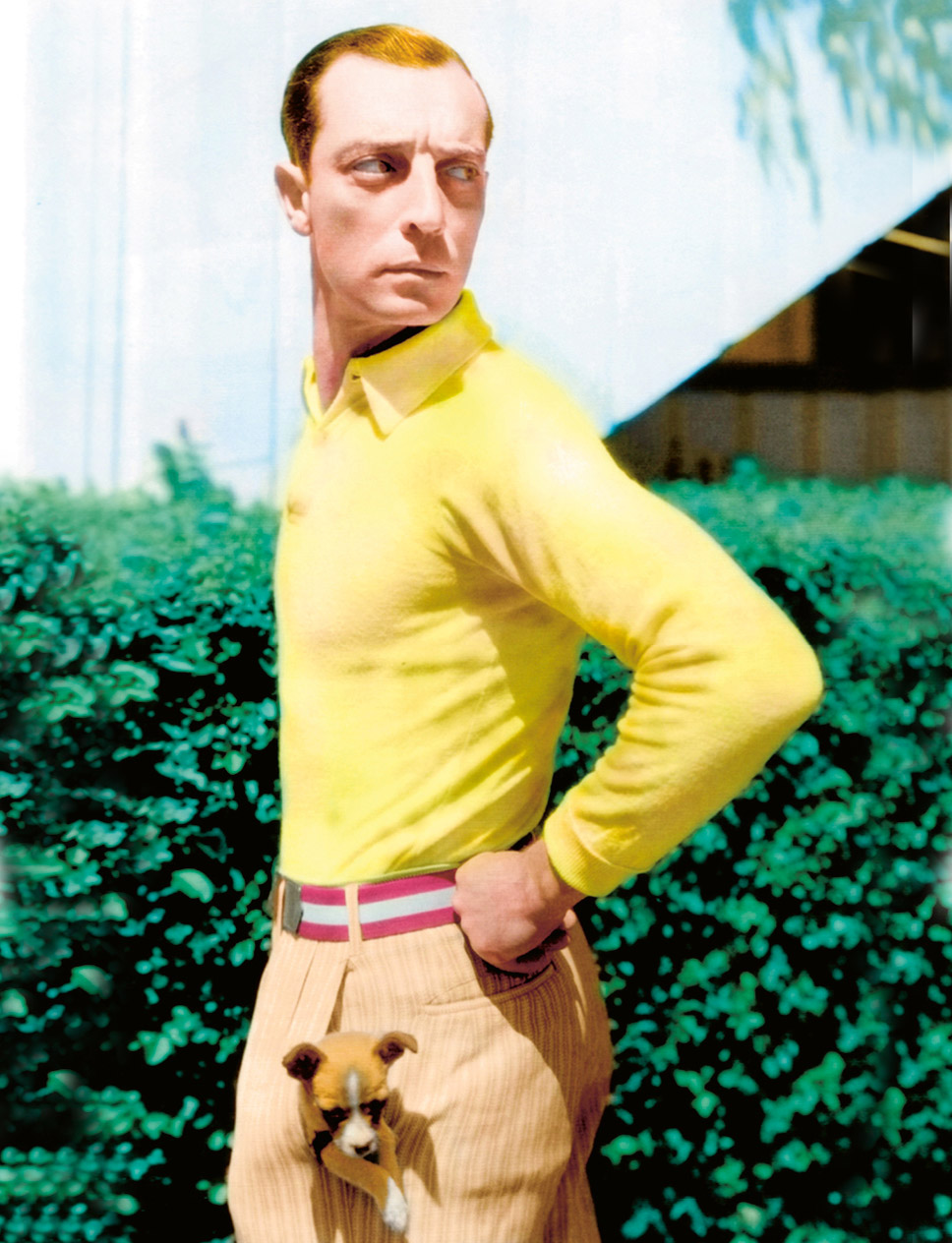

If you collect photographs of Buster, you soon notice how rare it is to see him in color. In those you can find, he looks as if he’s the subject of one of those fin-de-siècle hand-tinted portraits of a dead body that Victorian families cherished so intensely. There’s a ghoulishly thrilling painted snapshot from 1930: clown make-up drools exuberantly over his tragic face while Lon Chaney (who died that year) looks at him askance from his own portrait like a mean-spirited saint. In another shot from the same sequence, Buster appears in a vest—athletic, aglow, like he’s escaped from the pages of a fantasia by Jean Genet.

Between jobs during this bleak period in the 1930s, he was taking pratfalls on the streets for cash and drinking with tramps. In another sanatorium, he was subjected to “a reasonable facsimile” of the Keeley Cure: “Nurses and doctors do nothing but pour liquor into you, giving you a drink every half-hour on the half-hour. You get your favorite snort all right, but never twice in a row. Instead they start you off with whiskey and on succeeding rounds give you gin, rum, beer, brandy, wine—before they get around to the whiskey again. … When you plead, ‘Oh, no! Take it away please!’ all you get from your bartenders and barmaids in white coats is a friendly smile. ‘Please take it away,’ you repeat, ‘it hurts my stomach.’ ‘Just one more,’ they say, for their purpose is to make the hurt in your stomach grow until it becomes unforgettable.” There’s a blackly comic rhythm to this episode of aversion therapy that’s uncannily close to the circumstances in some of his films. All those doctors recall the hundreds of policemen pursuing poor Buster in Cops (1922), the wicked two-reeler that concludes with him locked up and his porkpie hat lying on a tombstone. In Hard Luck (1921), heartbroken and penniless, he repeatedly attempts to kill himself but always fails. On a darkened road he lies in the path of two looming headlights only for it to be revealed that the beams belong to a pair of motorcycles. In a rich man’s kitchen, he spies a bottle marked “Poison,” not knowing that a crafty dipsomaniac waiter has filled it with whiskey. As soon as he guzzles down that favorite snort, he swaggers off, then gets lost in the wilderness. The lurid horrors of his round-the-clock drinking in the sanatorium acquire an extra brutal kick when you learn that drenching the patient in alcohol was meant as only one part of the Keeley Cure, a turn-of-the-century treatment that seems to have been concocted in a medicine show performance of vulpine promise and pharmacological make-believe.

Leslie Keeley’s “Gold Cure” was struck upon as a commercial enterprise in 1879, claiming to conquer tobacco habits, opium addiction, alcoholism, and neurasthenia. “Fatty” Arbuckle might have submitted to a similar treatment when he beat his morphine addiction during World War I. The cure was a tonic of mysterious provenance that contained “Double Chloride of Gold,” strychnine—commonly purveyed as rat poison—and apomorphine. This mixture supposedly replenished the cells that had grown dependent on the addict’s favorite substance. The tonic could be purchased through mail order for patients who wished to kick their habit at home, but it was more often administered by injection, four times a day, at a Keeley Institute. By the end of the nineteenth century, every state in America had one of these institutes for the treatment of addiction and some had as many as three.[3] Upon admission, alcoholic patients were supplied with as much drink as they could stomach before being inducted into a four-week program of temperance and strictly regimented calm that forecasts the pastoral conditions of modern rehabilitation centers.

But Buster was subjected to a maimed version of the cure that sounds especially sadistic and effectively dragged him through the wild terror of a waking nightmare. Aversion therapy attempts to infect the patient’s memory with dark associations between what they crave and its effects so that, eventually, out of sheer revulsion, the desire might be conquered. Rates of relapse were high among those who underwent the Keeley Cure in its proper form, even if contemporary accounts sound breezily triumphant or like so much circus barking: “They went away sots and returned gentlemen!”[4] Buster was obliterated by the warped version of the cure he received twice in quick succession, and the second attempt was successful but not in the supernatural fashion that Keeley’s huckster advertising often claimed. Straight out of the sanatorium, he performed an act of private significance: “I walked to the bar and ordered two manhattans. I drank them one after the other. … I did not touch a drop of whiskey or any other alcoholic drink for five years.”

He resumed drinking at a gentler tempo after that. When he met Beckett in New York before the shooting of Film started, he was drinking beer and watching a baseball game on TV. He didn’t offer Beckett a drink—“maybe he thought a man like Beckett didn’t drink beer”[5]—and said almost nothing throughout their encounter, asking only if he could wear his familiar hat in the film.

As he aged, he grew bald, gristly, marble-eyed, hangdog, though rough traces of his youthful beauty remained. His job became making quick appearances in unexpected places. Always, in these later performances, he arrives from and returns to a becalmed region of the past. He appeared in Sunset Boulevard as one of “the waxworks” playing in Gloria Swanson’s bridge game. Television had kept the formats and rhythms of vaudeville alive so he was at home there. The audience’s applause at the end of these spots congratulated him for surviving. Greta Garbo went into the regal isolation that would continue until her death in 1990; Chaplin abandoned America for Switzerland. Buster stayed in Los Angeles, watched a lot of TV, and kept working up until his death from lung cancer in 1966. (One last, late snapshot: Old Buster smoking in a borrowed tuxedo, with a pensive macaque under his arm.) As you chase Buster’s ghost down these mysterious corridors, you never quite reach him, but it seems strangely resonant to note that he always had a very quiet voice.

- Beckett once received a request for permission to mount a Broadway production of Waiting for Godot where Marlon Brando would play Estragon and Keaton undertake the role of Vladimir. Nothing came of it. Keaton would have made a brilliant Lucky, the terrified serf whose role is almost entirely mute.

- All of Keaton’s quotes are taken from Buster Keaton and Charles Samuels, My Wonderful World of Slapstick (New York: Da Capo Press, 1982).

- See Mark Edward Lender and James Kirby Martin, Drinking in America: A History (New York: The Free Press, 1987), p. 123.

- This is the awed response of Joseph Medill, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, who initially did not believe the treatment would be efficacious. Quoted in William L. White, Slaying The Dragon: The History of Addiction Treatment and Recovery in America (Normal, IL: Chester Health Systems/Lighthouse Institute, 1998), p. 51.

- Alan Schneider, Beckett’s friend and director of Film, quoted in Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett (London: Bloomsbury, 1997), p. 512.

Charlie Fox is a writer based in London. He is currently at work on a book about recluses.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.