Gift of General Dodds

The plundering of Dahomey

Julian Lucas

I was visiting Benin, taking pictures of a palace in Abomey, when a prince with a machete made a grab for my phone. He was shirtless, angry, and wearing a beautiful slumped cap, done in black velvet and embroidered with silver stars. He was speaking Fon, but I could tell that he was angry—not with me but with my guide, who paraphrased their argument in French. Seated just behind him on the motorcycle, two languages removed, I tried to make out the details of our lèse-majesté.

The prince was a groundskeeper—that’s what the machete was for—but he was also accustomed to receiving royalties from visitors. This privilege, recently and without explanation revoked by the Bureau of Tourism, was an inheritance from his ancestor, King Tegbesu. Tegbesu had built the palace that crumbled behind us, now nothing more than a gate with walls, a blood-red heap under the sky’s chalk-dusted blue. Photographing, even just looking at this heirloom, would cost money. So we gave him a few thousand francs and drove off. As he shrank with the walls, I watched him stuff the colorful bills down the front of his pants, leaving, on the sparkling hair below his navel, a smear of orange earth.

• • •

On 16 November 1892, French troops reached Abomey, then capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey. The city was in flames, burned by King Béhanzin when France refused his terms of surrender. He began with his own sprawling compounds, then set fire to the homes of his subjects, compelling everyone to follow his retreat. The blaze was three kilometers wide, and it scorched the city’s sanguine walls to pitch. Guerrilla struggles would follow, but this was the formal conclusion of the Franco-Dahomean Wars, one front in the “scramble for Africa” which by 1914 would leave nearly the entire continent in European hands. The conflict began in 1890, when the French—already master of large swaths of West Africa—turned their pith helmets and howitzers on Dahomey, their partner for centuries in the slave and palm oil trades. Nine months of fighting won them rights to the port city of Cotonou. And in 1892, after a short truce, France came back to take the whole kingdom. The press pitched in before this second war even began. Three months before the start of the campaign, Le Petit Journal printed a color lithograph of King Béhanzin, enthroned among skulls and guarded by a woman warrior. “He doesn’t speak a single European language,” the article remarks. “Our country will easily finish him.”[1]

The man who did the finishing was Colonel Alfred-Amédée Dodds, a Senegalese métis and one of the most experienced officers in the French colonies. Dodds had put down riots on the Indian Ocean island of Réunion, led expeditions against the Serer and Fula in Senegal, and played a decisive role in the capture of what is now Hanoi, Vietnam.[2] Now in Dahomey, less than six months after his arrival, he had all but destroyed West Africa’s most powerful independent state. His troops entered Abomey on the morning of 17 November, setting up their bivouac in the still-smoking ruins of Béhanzin’s palace. They were a mixed bunch—pith-helmeted French marines, Senegalese cavalrymen, allied warriors from the nearby kingdom of Porto-Novo, and hundreds of local porters, two of whom carried Colonel Dodds to the city in a hammock.[3]

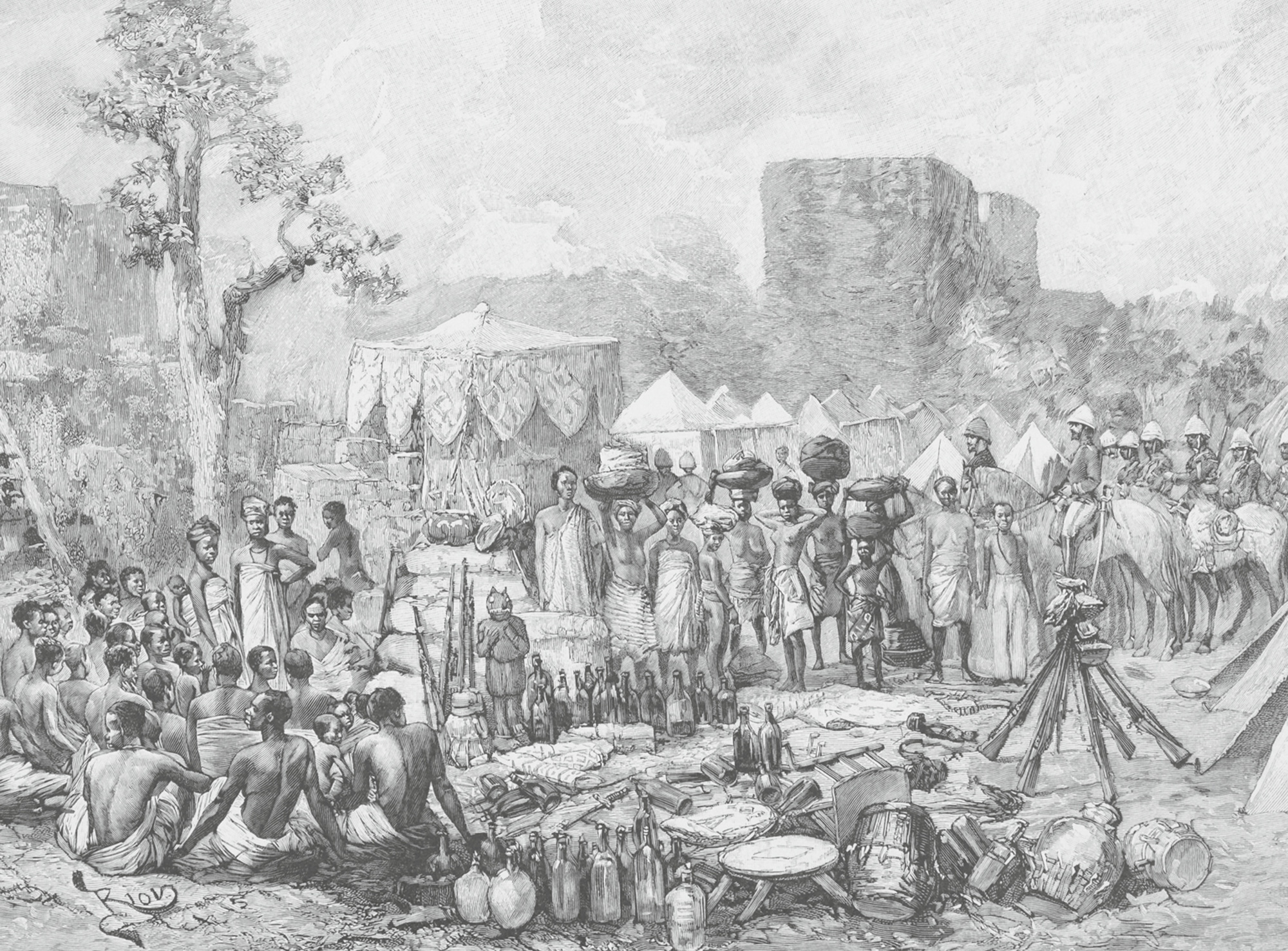

Looting began almost immediately after the French flag was hoisted over Béhanzin’s palace. The invaders, primed by travelers’ tales of Abomey’s wealth, were quickly disappointed by the king’s leavings—mostly alcohol, textiles, and half-functioning guns. But the mood of anticlimax quickly lifted. Soldiers, drunk on the king’s Dutch gin, gamboled through the ruined courtyards in billowing Dahomean skirts, taking shade under the huge appliquéd parasols of courtiers. They turned over the soil, and found under it cannons, blunderbusses, statuettes, bracelets and necklaces of cowrie shell and coral—a city’s worth of hurriedly hidden treasures. The clearing before the colonel’s tent became “a veritable bazaar” of plunder.[4]

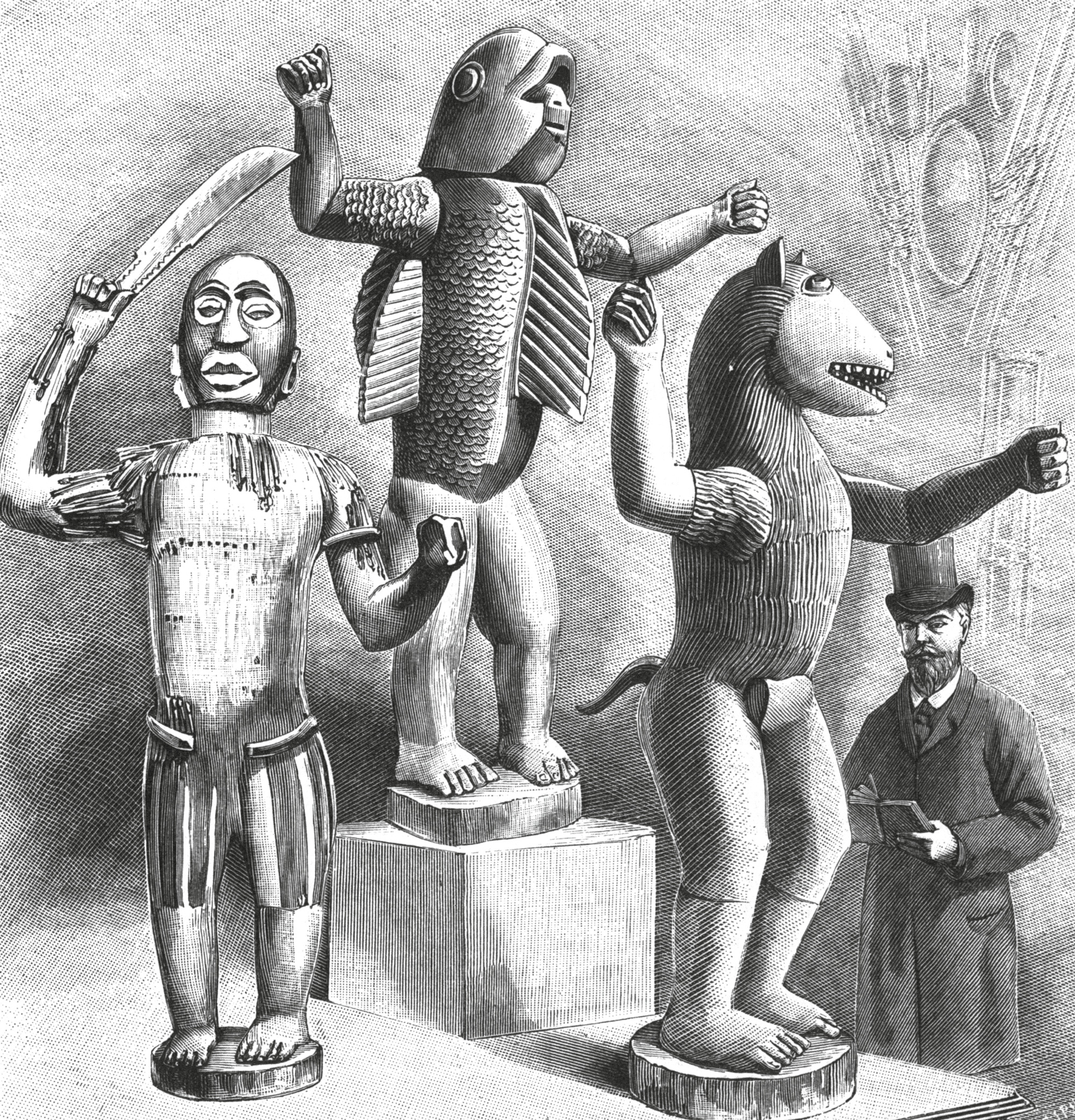

The ordinary soldiers took what they could, anxiously watching the bulging parcels of their officers, whom they suspected of requisitioning the best of the loot. They were right. Dodds, promoted by telegram to the rank of general, had amassed a collection of artifacts including silver scepters, ancestral altars, intricately carved palace doors, and King Béhanzin’s golden throne. But the real prize was a set of three therianthropic statues, life-sized half-man, half-animal portraits of Dahomean kings. These were the royal bocio, magic battle standards hewn by the court carver, Sosa Adede, from the trunks of trees. A sword in each hand, looming over the troops, the bocio were wheeled to the front lines of battles. They were expected, in urgent circumstances, to come alive and fight.[5]

Le Petit Journal had published lithographs of other “garish … painted gods,” captured in an earlier battle, whose powers had failed to save them from “our heroic little soldiers.” But it might be nice, an editorialist mused, if the marines brought “us back some of these spiteful guardians of the Dahomeans … they won’t miss the wood.”[6] The writer got his wish. In 1893, Dodds donated his finest finds, including the three bocio, to Paris’s Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. Since then, the three royal bocio have been almost continuously on display in Paris—first as trophies, then as ethnographic curiosities, and finally as works of art. Millions of people have seen them, including Pablo Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire, who visited them at the Trocadéro before it closed in 1935.[7] They were then moved to the ethnographic Musée de l’Homme.

Since 2006, they have been held by the Musée du quai Branly, a controversial rebranding of France’s larcenous legacy as a broad-minded homage to non-Western art. The Dahomean bocio are mounted on three high cylinders in the main collections hall. Guezo, broad-chested and iron-colored, leaning back as though about to strike; Glele, the lion, his blunt snout snapping with tiny, filed teeth; and Béhanzin, the shark, green as a tank and missing a portion of his fearsome jaw. Frozen in the bent-legged, forearm-out posture of fencers, the statues stand back-to-back in a defensive huddle—staring, as though encircled, at the dimly lit expanse. At the base of each figure, a small plaque reads, “Gift of General Dodds.”

• • •

The plunder of art is now recognized as a crime under international law. A latter-day Dodds would have to contend with more than half a century of treaties, the most important of which, the 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property, was adopted after the looting of European museums and private collections during World War II.[8] This convention and the treaties that followed it have frequently been observed, even by powerful occupiers with little incentive to do so.[9] But the treasures of Dahomey, stolen sixty years too early, are still subject to the “finders keepers” convention. Excepting the occasional “loan” of smaller pieces to museums in Benin, they seem likely to remain where they are, if not without objection.[10] In 2013, Nicéphore Soglo, former president of Benin, and Louis-George Tin, head of CRAN (the representative council of black associations in France), called for the return of France’s “biens mal acquis” (ill-gotten gains) in a strident editorial for Le Monde.[11] It was about as effective as Béhanzin’s bocio were on the battlefield—which is to say, not at all.

But one can dream. In Ishmael Reed’s satirical novel Mumbo Jumbo (1972), a multinational cell of art thieves called the Mu’tafikah orchestrate an elaborate plan to liberate the “Ikons of aesthetically victimized civilizations” from “Centers of Art Detention” across Europe and America. The masterstroke in their worldwide effort is a heist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they plan to seize a massive Olmec head from Mexico. Art world warriors from every continent, the members of the Mu’tafikah plan not just to return what was stolen, but to create “renewed enthusiasms” for non-Western traditions.[12] Restoration is not merely a remedy for past injustice, but the beginning of new creation.

One Beninese artist who would make a good Mu’tafikah is Romuald Hazoumè, who recently exhibited an unusual egungun at the Fondation Zinsou gallery in Cotonou. This sacred Yoruba masquerade, a representative from ancestral spirits, is traditionally a sumptuous, sequined costume, veiled in a long fall of cowrie shells. But Hazoumè’s, no less elaborate, is made of street trash, assembled from the kerosene canisters that litter every corner of motorcycle-choked Cotonou. Garishly red, blue, yellow, and black, it trails its greasy skirts before the reverent crowd—a gathering of canister faces arranged in a semicircle around it. These are only surrogates for the work’s ultimate audience. Hazoumè has offered the mask, and others like it, in exchange for the real Yoruba egungun detained in Western museums. But he has received no answer. From the world’s Centers of Art Detention has come only that sound so familiar to their visitors—silence.

- See Jean Bayol, “Behanzin: Roi du Dahomey,” Le Petit Journal: Supplément Illustré, 23 April 1892. The original reads: “Il ne parle aucune langue européene. … Notre pays viendra facilement à bout.” The entire run of the newspaper is available online at catalogue.bnf.fr.

- For biographical information about Alfred-Amédée Dodds, see François Desplantes, Le général Dodds et l’expédition du Dahomey (Rouen: Mégard et Cie, 1894).

- Meanwhile, Béhanzin retreated to the Couffo river, where he became so distraught that he cut off his elderly mother’s head. She was to bring the kingdom’s pleas for help to her deceased husband, King Glele; the hoped-for ancestral intercession never arrived. Béhanzin would soon be captured and exiled to Martinique. See Edna Bay, Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012), p. 304.

- Alexandre L. d’Albéca, La France au Dahomey (Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1895), p. 111. The original reads: “Au bout de quelques jours, devant la tente du général, on a un véritable bazar.” For other soldiers’ accounts, see Jules Poirier, Campagne du Dahomey (Paris: Imprimerie Librairie Militaire, 1895); François Michel and Jacques Serre, La campagne du Dahomey, 1893–1894: La réddition de Béhanzin (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2001).

- For an analysis of royal bocio, see Suzanne Preston Blier, “Power, Art, and the Mysteries of Rule,” in African Vodun: Art, Psychology, and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), pp. 315–346.

- See “Au Dahomey,” Le Petit Journal: Supplément Illustré, 26 November 1892. The original reads: “J‘espère qu’ils nous rapporteront en revenant quelques-uns de ces mauvais protecteurs des Dahoméens; ceux-ci d’ailleurs seront quittes pour en tailler d’autres; le bois ne leur manque pas.” Exhibiting more of the same venomous curiosity, the paper later published an engraving of their fallen enemies’ incinerated corpses. The writer of “Crémation des cadavres dahoméens” in the 3 December 1892 edition of Le Petit Journal: Supplément Illustré notes: “Curious detail: After their death, the skin of the Dahomeans flakes off and becomes less black.” The original reads: “Détail curieux: Après leur mort, la peau des Dahoméens s’écaille et devient moins noire.”

- For the reception history of the bocio, see Julia Kelly, “‘Dahomey!, Dahomey!’: The Reception of Dahomean Art in France in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries,” Journal of Art Historiography, no. 12 (June 2015), pp. 1–19; Gaëlle Beaujean-Baltzer, “Du trophée à l’œuvre: Parcours de cinq artefacts du royaume d’Abomey,” Gradhiva, no. 6 (November 2007), pp. 70–85.

- No similar outrage was occasioned by the expropriation of art from the overseas colonies of European countries, evidence for Martiniquan writer Aimé Césaire’s claim that Hitler was unforgivable because he did to Europe what until then had only been done to Europe’s colonial subjects. See Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), p. 36.

- Carol A. Roehrenbeck, “Repatriation of Cultural Property—Who Owns the Past? An Introduction to Approaches and to Selected Statutory Instruments,” International Journal of Legal Information, vol. 38, no. 2 (Summer 2010), p. 199. After the invasion of Afghanistan, coalition governments returned tens of thousands of stolen artifacts to Kabul’s National Museum.

- To commemorate the centennial of King Béhanzin’s death, in 2006 the Musée du quai Branly loaned Beninese museums several small artifacts from its Benin collection. Béhanzin’s throne and bocio were not among them.

- Louis-Georges Tin and Nicéphore Soglo, “Appel concernant les biens mal acquis de la France,” Le Monde, 10 December 2013.

- All quotations from Ishmael Reed are from Mumbo Jumbo (New York: Scribner Paperback Fiction, 1996), p. 15.

Julian Lucas is a writer from New Jersey and associate editor of Cabinet. He has published in the New York Review of Books and the Harvard Advocate, where he edited the 2015 “Possession” issue. He is currently working on a series of essays about historical reenactments, computer games, and the Underground Railroad.