Language at the End of the World

The undecipherable rongorongo script of Easter Island

Jacob Mikanowski

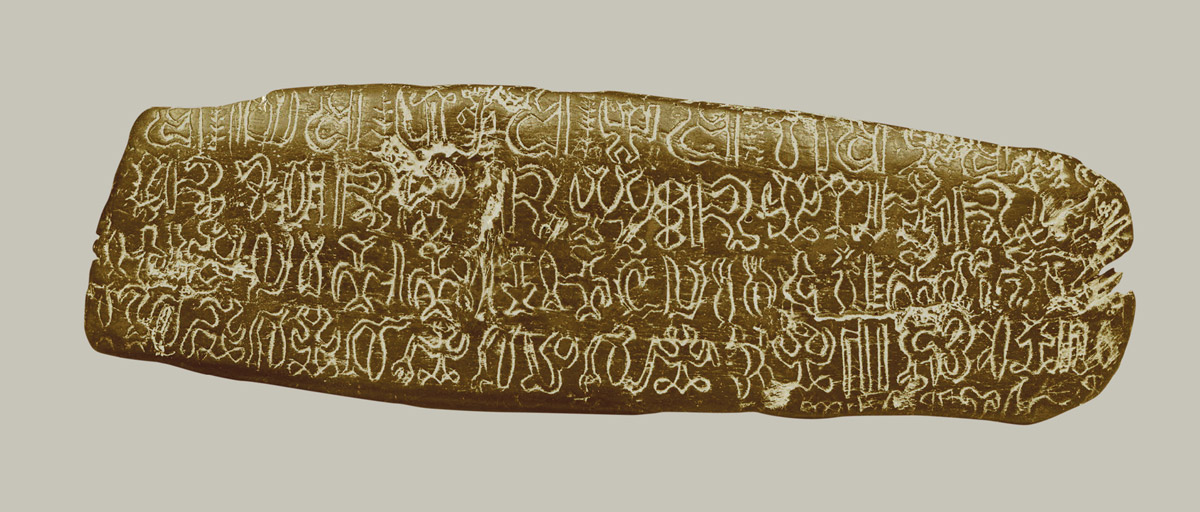

Of all the literatures in the world, the smallest and most enigmatic belongs without question to the people of Easter Island. It is written in a script—rongorongo—that no one can decipher. Experts cannot even agree whether it is an alphabet, a syllabary, a mnemonic, or a rebus. Its entire corpus consists of two dozen texts. The longest, consisting of a few thousand signs, winds its way around a magnificent ceremonial staff. The shortest texts—if they can even be called that—consist of barely more than a single sign. One took the form of a tattoo on a man’s back. Another was carved onto a human skull.

Where did the rongorongo script come from? What do its texts communicate? No one knows for sure. The last Easter Islanders (or Rapanui) familiar with rongorongo died in the nineteenth century. They didn’t live long enough to pass on the secret of their writing system, but they did leave a few tantalizing clues. The island’s spoken language, also called Rapanui, lives on, but today it is written in a Latin script and its relationship to rongorongo is unclear. So far at least, no one has successfully connected one with the other. To this day, rongorongo remains a puzzle, an enigma, and a mirror for the folly of those who try to solve it.

Rongorongo is the only script native to the Pacific. Like so much else, it makes Easter Island unique. It is the most isolated inhabited place in the world; an old name for it, Te Pito ‘o te Henua, means either “navel of the world” or “end of the world.”[1] It is over a thousand miles from the nearest speck of land. The prevailing winds could make a sea voyage to central Polynesia a journey of over ten thousand miles. Only sixty-three square miles, the tiny island is a triangle with a base of fourteen miles and a height of eight. It can be circumambulated in a day. To the people of Easter Island, the universe was an ocean, and the earth a speck of land on top of it. From somewhere to the west came the canoes of the ancestors. From the north and south came great flocks of migrating birds.

The stillness of this isolation was shattered on Easter Day, 1722, when the island was spotted by the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen. He and his crew came ashore for one day, traded their cloth for chickens, and shot a dozen islanders, including the emissary who had arrived on their ship to welcome them the day before. After five days, they set sail. No other Europeans visited for the next forty-eight years, when a Spanish ship under the command of the viceroy of Peru made a reconnaissance. The Spanish named the island San Carlos, and claimed it in the name of their king, Carlos III. To make the transfer official, the Spanish commander, Felipe González de Haedo, asked the island chiefs to put their mark on a document of cession. The Spaniards surrounded the event with great pomp: drums, fifes, flags. The Rapanui chiefs signed the document as best they could, with sketches of vulvas and frigate birds, signs familiar from the island’s abundant rock art.

Then the Spanish left. Their claim, and the name San Carlos, were both swiftly forgotten. But their short stay left a profound impression on the Rapanui. After the visits of the Europeans, they began to construct “earth ships,” mounds the size and shape of a boat, surrounded by a ditch that, when filled with water, gave the impression of a ship floating at sea. Katherine Routledge, a pioneering ethnographer of Easter Island life, was told by her informants that the Rapanui would use these earth ships to “gather and act the part of a European crew, one taking the lead and giving orders to the other.”[2] In this way, they communed with “the men who came from far away” who “had pink cheeks and said they were gods.”[3]

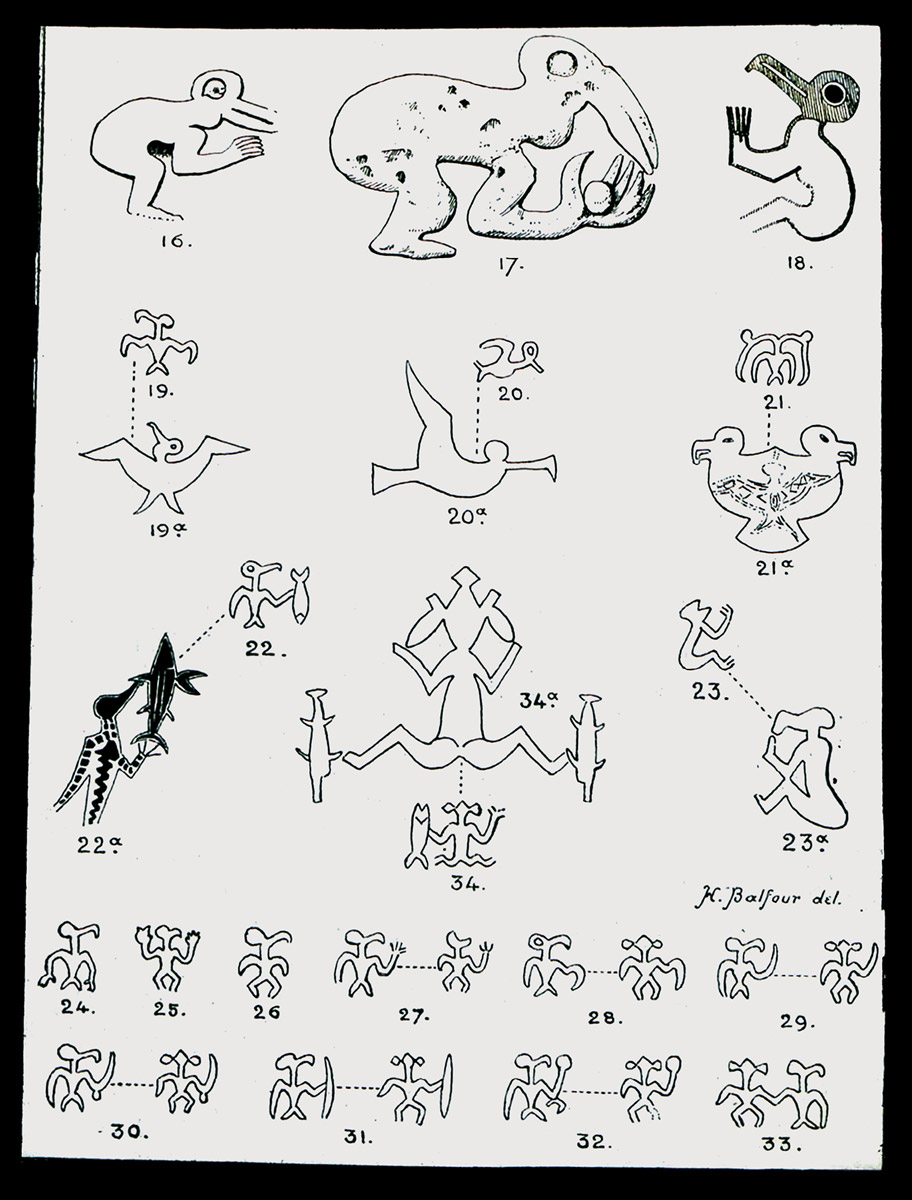

The earth ships appear to have been an attempt by the Easter Islanders to duplicate foreign technology in the form of magic. Something similar may have happened with rongorongo. The Rapanui seem to have intuited the concept of writing, and the power of literacy that came with it, and then set about creating a system of their own. When they did so, they began entirely afresh, building it from first principles and local materials. As a consequence, it resembles no other writing system on Earth. The signs they chose come largely from items familiar to the island. Some come from animal life: fish, squid, sea turtles, crayfish, frigate birds, caterpillars. A few seem to represent plants or human figures, sitting and eating. Others are simple geometric forms: a circle, a cross, stacks of lozenges.

The glyphs of rongorongo are unique. So is the manner in which it was written and read. In fact, it was not written, but carved. Its scribes used shark’s teeth to inscribe its symbols on wooden tablets. Wood is scarce on Easter Island, and most of these inscriptions were made on pieces of driftwood. One decorated an oar. A second, a beam. A third, a statue of a bird. However, most of the surviving examples of rongorongo decorate square tablets. These appear to have been written from bottom to top, and were read following a pattern called the reverse boustrophedon. Boustrophedon is a Greek word meaning “in the manner of an ox,” and scripts written in it move like an ox plowing a field, reversing direction with each line.

How did the Rapanui go from signing their names to a bogus document of annexation with simple drawings to creating a complex writing system incorporating hundreds of signs? We will most likely never know. First contact with Europeans was a trauma, one to which the Rapanui responded with incredible creativity and cultural ferment. But peering into the history of how this happened is unfortunately almost impossible, for it means looking through the scrim drawn by a holocaust.

The trouble began in 1861, when a Dubliner named Joseph Charles Byrne arrived in Peru with a proposal to cure that country’s labor shortage. He suggested that instead of searching the world for willing immigrants, they trade in indentures, and use the vast pool of humanity on their doorstep. What this really meant was the wholesale enslavement of Pacific islanders. In 1862, the first of the large-scale slave raids arrived. Within the span of a few years, most of the island’s population was deported and enslaved. Some of the surviving Rapanui ended up on Tahiti, where they succumbed to disease and starvation. By 1871, approximately 94 percent of Easter Island’s population had been forced to move elsewhere or had died. Only a little over a hundred people remained, the majority of whom had been forced to work on sheep farms. It was, in the words of one historian, “one of the greatest human losses registered anywhere in the Pacific at this time.”[4]

Buzzards came to feast on what remained. In the 1870s, a French rancher, Jean-Baptiste Doutrou-Bornier, attempted to purchase the entire island. A megalomaniac and a sadist, he nearly succeeded. He drove off Catholic missionaries with fire, surrounded himself with kidnapped consorts, and declared himself a king. After a few years, he owned 80 percent of the island’s land and over four thousand sheep. A year later, he was killed in an ambush. Other pirates came to take his place. Easter Island became a prison, a work camp for the few people who hadn’t been kidnapped or driven away. The old ways, and especially the arts of literacy, held by a narrow elite, all vanished. However small as a speck of land, the island had been home to a full-fledged civilization, with its own architecture, myths, rulers, and rites. Now all was in ruins.

It was in the midst of this disaster that the world became aware of rongorongo. In 1864, Joseph-Eugène Eyraud, a member of the Catholic mission on the island, noticed in all the houses tablets and staffs inscribed in an unknown script. He did not succeed in learning what it expressed. Curiously, no previous visitor to the island had ever observed them, perhaps because of a taboo. Four years later, the bishop of Tahiti, Florentin-Étienne Jaussen, received a piece of polished rosewood, wrapped in human hair, from one of his parishioners, a Rapanui convert. He was amazed to discover that it was covered in an unknown form of hieroglyphs. He immediately wrote to the Catholic mission on the island, asking them to search for more examples of the unknown script. They were only able to turn up a few. One man questioned by the bishop confessed “that there was nobody left on the island who knew how to read the characters since the Peruvians had brought about the deaths of all the wise men.”[5] The tablets had thus lost all their potency. In the absence of literacy, the tablets, once objects of sacred power, became simply pieces of wood. They were burned for heat and used as reels for fishing lines. According to rumor, one Rapanui man even cobbled together a canoe out of them.

For the next two decades, little more was learned about rongorongo script. One potential breakthrough came in 1886, when Ure Va‘e Iko, a steward of the last paramount chief of Easter Island, “read” one of the tablets for a visiting American naval officer, William Judah Thompson. Ure took some convincing. Now Christian, and not wanting to do something forbidden by the priests, he initially refused payment and fled to the hills. Eventually, though, he was made to comply.

It isn’t clear whether Ure was reading from the tablet, or whether he even knew the rongorongo script. It seems he may have known it at one point, but had forgotten it by the time he met with Thompson. One of the chants he delivered, a “procreation chant,” details a series of paradoxical and, indeed, baffling couplings: “Itchiness copulated with Badness: There issued forth the kape taro”; “Parental God copulated with the Slimy Vagina of God: There issued forth the deep sea”; “God Parent copulated with Compacted Sand: There issued forth the tree”; “The fish Rat-Tail copulated with Maggoty Hina: There issued forth the whale.”[6]

Ure’s words appear to be unconnected to any specific tablet. Instead, they are the words of a traditional chant, the first thing students in rongorongo schools memorized before they proceeded to master the script. Still, it gives some sense of the flavor of what the tablets might contain. (Indeed, according to the leading modern scholar of rongorongo, it is the key to deciphering them all). But in the 130 years since Ure delivered his recitation, very little progress has been made in decoding rongorongo. Undeciphered scripts work like Rorschach blots. Lacking a defined meaning, their inscrutability allows their would-be interpreters to project all their fantasies, wishes, and desires onto the blank space they hope to fill in. This was the case with Egyptian hieroglyphics before Champollion, and with Mayan glyphs before Knorozov. It remains the case with rongorongo.

The process of fantastical translation began early, with one Dr. Allen Carroll, a Sydney physician who may have been the illegitimate son of the Duke of Norfolk and who believed the tablets to be the work of pre-Inca South Americans. Carroll’s translations take the form of fulsome paeans to unnamed gods, and sound a bit like bowdlerized versions of the rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam: “To those who are our Guardians, oh give ear to us in your temple. You are our protectors. … Ye gods.”[7]

Carroll was the father of the so-called “rongorongo fringe.” Many more followed in his footsteps. Most share a single, driving idea: the conviction that the Rapanui could not have invented their script on their own. The islanders’ writing was necessarily the mark of an older, greater civilization, they believed. All agreed it must have come from somewhere else. Where exactly it came from was the only thing left to debate.

Erich von Hornbostel saw connections with the pictographs of the Panamanian Cuña and the unintelligible signs of the Yü Pei.[8] Guillaume de Hevesy, a Hungarian engineer resident in Paris, sparked an uproar in the 1930s when he discerned a genetic link between rongorongo and the equally undecipherable Indus script found at Mohenjo Daro. An industrious, though confused, Argentine professor tried to fit it into a graphic system spanning the entire Indo-Pacific. A German paleontologist found traces of rongorongo glyphs in the patterns of Sumatran ship fabrics. Peter Lanyon-Orgill, a polyglot and possibly insane Cornishman, found hints of them everywhere from Land’s End to Zimbabwe, and created his own journal to publicize his findings. One Swiss scholar believed they represented the remains of a Pacific empire that had sunk into the sea. A psychologist at Bard was convinced it arrived in Easter Island from Egypt, via the “Asiatic Script Bridge.” The Polish folklorist Henryka Romanska discerned in one of the tablets a hymn to the sun god Ra. In her rendering, it sounds strangely like a pastoral composed by an Edwardian author with repetition compulsion: “The bird gladly with the flower flies / The bird gladly with the fruit flies.”[9]

The members of this group, with their errant but earnest efforts to link rongorongo to real events in human antiquity, seem positively levelheaded compared with what came next: fifty years of speculation about aliens, giant tidal waves, shipwrecked Spaniards, and the lost continent of Mu. But while the fantasists were at work, a body of rongorongo-related scholarship more grounded in reality arose as well.

In the 1940s, Alfred Métraux proved conclusively that the Easter Island script had no connection to the civilizations of the Indus. A querulous, foul-tempered Frenchman, he stepped in to lead a scientific expedition to the island when its original leader died of pneumonia off Cape Horn. Some twenty years later, his body was found near the Château de la Madeleine in the Vallée de Chevreuse. In his journal, he wrote that he died “like Socrates.”[10] The true culprit appears to have been a love affair gone awry.

The most sustained effort to decipher rongorongo rooted in professional linguistics took place in St. Petersburg. The dogged work of the Russian school helped to sort the script into a clear inventory of signs. Through the use of internal analysis and statistical comparison, its members hoped to place the study of the script on a firm scientific basis. But their careful analysis yields results that nonetheless sound insane—in Irina Fedorova’s translation, one text ends: “yam, yam, taro, taro, he cut a tuber of yam, he took a tuber of taro, a tuber, a tuber, he dug up, he cut, he cut, taro, turi sugar-cane.”[11]

For all the effort that has gone into them, none of the translations done so far provides a reliable guide to what the rongorongo tablets actually contained. Ure Va‘e Iko’s recitation to Thompson offers a possible thread, but it may say more about the Rapanui oral tradition than the written one. We do know that the oral tradition was vast, and varied. Most of it was sung. According to one early commentator, Rapanui songs expressed “the surprise of being alive and also the sadness of life.”[12] Whether the tablets do the same remains to be seem. Our best indication of what the rongorongo script was used for comes, however, not from songs or attempts at deciphering, but from ethnographic data, especially that gathered by Katherine Routledge in 1914 from some of the few Rapanui elders who survived the holocaust of the 1860s.

Routledge was a remarkable woman, who has been unjustly forgotten. She was the daughter of a wealthy Quaker family, which made a fortune manufacturing brick in northern England. She showed an independent streak early on, graduating from Oxford with a degree in modern history and traveling to South Africa as part of an investigative committee after the Second Boer War. In 1906, she married an Australian adventurer named William Scoresby Routledge. Together, they settled in Kenya, where Katherine studied the customs of the Kikuyu and Scoresby quarreled with everyone he met. In 1910, they decided to head to Easter Island to learn what they could about its monumental statues. They had a yacht specially built for this purpose, and hired a crew of eager young Englishmen, most of whom quit during the year it took to sail to Easter Island. They arrived in 1914, in the midst of a diplomatic crisis caused by the outbreak of World War I. While German cruisers rendezvoused offshore, Katherine immersed herself in the culture of the island. Together with her husband, she explored caves and documented fallen statues. Her most valuable work, though, came from speaking with the few old people who remembered life on the island before the arrival of the Peruvian slavers. Her best informants were two elders, Kirimuti and Tomenika, confined to a leper colony in the north of the island.

Their memories reached back to the 1850s, when the island was still ruled by Nga‘ara, an ‘ariki mau, or paramount chief. King Nga‘ara, as he is sometimes called, reigned from sometime in the mid-1830s to the time of his death in 1859. During this time, he elevated literacy to almost the status of a religion. He seems to have considered the teaching and learning of rongorongo as one of his most important tasks. He spent his days traveling around the island, visiting the various rongorongo schools and interrogating their pupils about their progress in the script. He would hold a tablet up and make a student read it. If they did well, he would clap loudly and give rongorongo artifacts to their teacher. If they did poorly, he would blame the teacher and confiscate their tablets.

The cult of literacy culminated every year at the annual ‘Anakena festival. Held on a sacred beach, said to be the first place the original migrants to the island put to shore, the festival drew hundreds of people in a celebration of reading and recitation. All day, rongorongo experts would read their tablets in front of a crowd waiting to applaud their successes and jeer their failures. At the end of the day, the king would mount a platform held aloft by eight men and lecture the bards on their duty to perform well. Then he would give each man a chicken.

Later in life, Katherine Routledge went mad. Her family blamed the malign influence of a Rapanui prophetess named Angata, with whom she was close. More likely, she succumbed to the paranoid schizophrenia that afflicted her brother. She spent her last days in an asylum, and her notes were left in the archive of the Royal Geographic Society, where they were mostly forgotten.[13] Combined with testimonies gathered by a few other researchers, they allow us to piece together a rough inventory of the various uses to which rongorongo tablets were put. Some were hymns in praise of chiefs. Some listed the names of people killed in battle. A great many of the inscriptions were charms. The written word was a conduit of magical power, which could be harnessed for various ends. Some tablets could save people from danger. Others dealt with vengeance: a timo tablet had the power to kill a murderer. A pure tablet could enhance fertility. Songs incised on artifacts could increase the harvest or the size of a catch. This may explain why they went unseen before Joseph-Eugène Eyraud’s arrival in 1864. The most significant piece of information, though, from Routledge’s informants might be the detail about the schools. It took pupils only a few months to master rongorongo. As Steven Fischer, the current leading student of the script writes, “If the little Rapanui children could learn it,” then “so can we.”[14]

Fischer thinks he has the rongorongo problem scotched. In his reading, the various tablets are all procreation texts—endless series of begats and begettings, tying living Easter Islanders to their mythical ancestors. As is usual in the tiny, querulous world of rongorongo studies, his opponents disagree, accusing him of misreadings, false assumptions, and other methodological inadequacies. Fischer remains convinced that he is right, but one thing does give the self-proclaimed “glyphbreaker” (the title of his autobiography) pause. As he notes in his vast scholarly tome on the script, one of Routledge’s informants told her that her husband used to stay up at night reading his cache of rongorongo tablets. She used to hear him reading, and when he did so, he would periodically “stop in the middle and chuckle.”[15]

What was he laughing at? It seems unlikely to have been a ritual formula. Whatever the rongorongo texts really say, they upend all our expectations of the nature of literacy. It was created in a place without cities, or even, really, commerce. Its inscriptions had the force of magic, but their meanings were not in themselves sacred. It is an unbreakable cipher, yet it could be mastered by children. Best of all, by refusing to be decoded, rongorongo mocks the primacy of Western reason. May it forever remain a riddle we can’t parse, a joke whose punchline is forever slipping from our grasp.

- Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo, The Statues That Walked: Unraveling the Mystery of Easter Island (New York: Free Press, 2011), p. 4.

- Ibid., p. 154.

- Ibid., p. 155.

- Steven Roger Fischer, Island at the End of the World (London: Reaktion Books, 2005), p. 86.

- Stéphen-Chauvet, L’île de Pâques et ses mystères (Paris: Éditions Tel, 1935), p. 381.

- Steven Roger Fischer, Rongorongo: The Easter Island Script (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), pp. 97–99.

- Ibid., p. 111.

- Ibid., p. 144.

- Ibid., p. 241.

- Ibid., p. 171.

- Cited in Igor Pozdniakov and Konstantin Pozdniakov, “Rapanui Writing and the Rapanui Language: Preliminary Results of a Statistical Analysis,” Forum for Anthropology and Culture, no. 3 (2006), p. 96. A PDF of this article, albeit with different pagination, is available at pozdniakov.free.fr/publications/2007_Rapanui_Writing_and_the_Rapanui_Language.pdf. In this document, the quotation appears on page 10.

- Steven Roger Fischer, Rongorongo, p. 303.

- Most of the information in this paragraph and the one above is derived from Jo Anne Van Tilburg, Among Stone Giants: The Life of Katherine Routledge and Her Remarkable Expedition to Easter Island (New York: Scribner, 2003).

- Steven Roger Fischer, Rongorongo, p. 347.

- Ibid., p. 282.

Jacob Mikanowski is a writer and critic based in Berkeley, California. His work has appeared in publications including Aeon, the Atlantic, the Guardian, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the New York Times, and Slate. Previously, he studied and taught European history and anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.