Psychoanalysis and the Machines

From Félix Guattari’s A Love of UIQ to Siri and Cortana

Alfie Bown

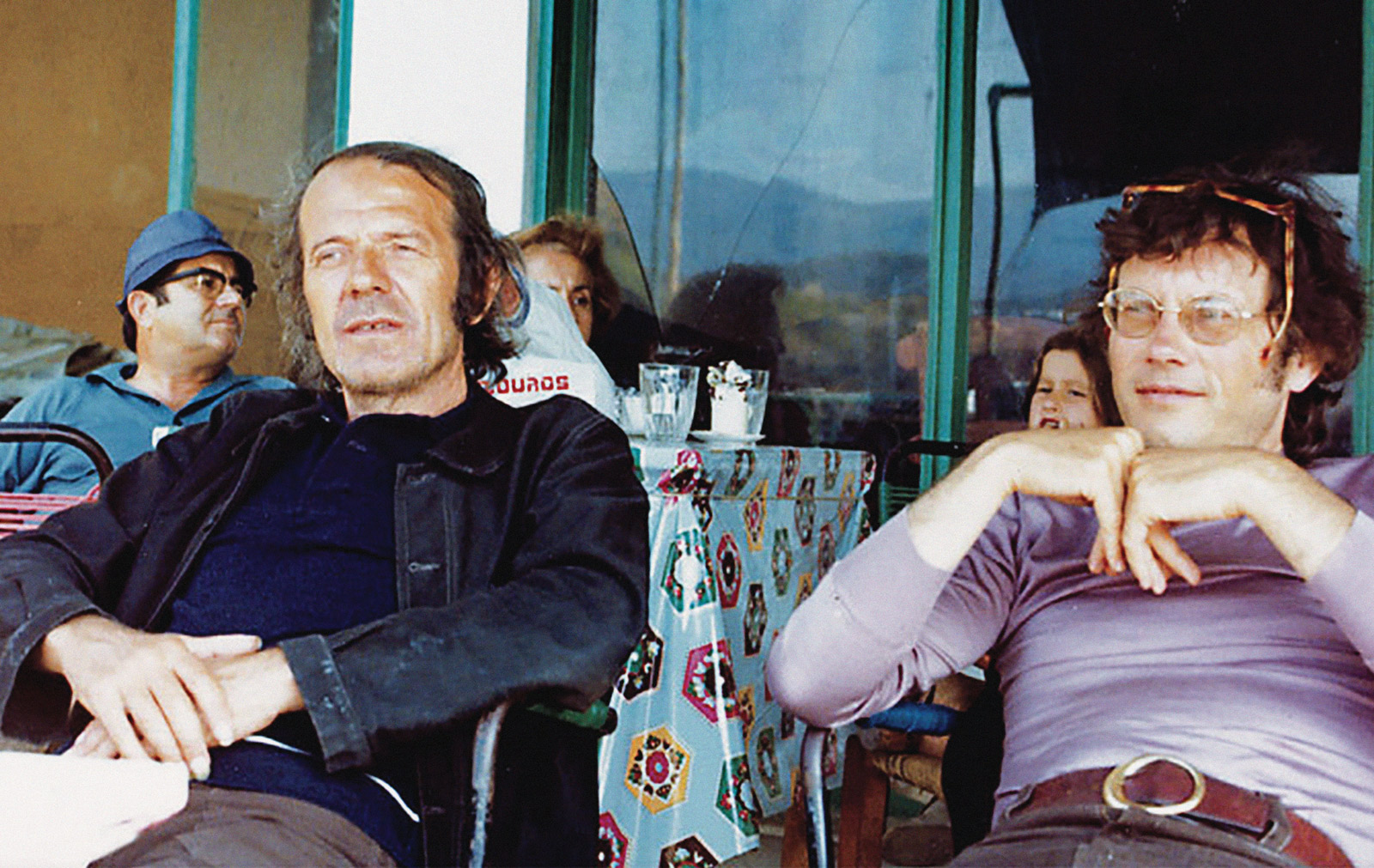

In 1987, with no experience in filmmaking whatsoever, Félix Guattari sent a script for a mad and bizarre science fiction movie called A Love of UIQ to France’s National Center for Cinematography. He attached his CV and hoped (probably even believed) that it would go all the way to Hollywood. Earlier in the decade, he’d even asked the legendary director Michelangelo Antonioni to get involved with the project. Unsurprisingly—and for many reasons—the film was never made. Had it been, we’d have had an early warning about the future power of technology to transform subjectivity, a reality that has now well and truly emerged. Even more importantly, it would have provided a call for a machinic subjectivity to help combat the contemporary identity crises created by technological advances. This machinic subjectivity would finally achieve what Guattari had long hoped to do: render psychoanalysis useless.

In 2016, the first English translation of A Love of UIQ appeared, the most recent of the many Guattari texts published in English over the last two decades (by Continuum, by Semiotext(e), and now by Univocal).[1] Each of these has made a ripple in academic and philosophical discussion, and yet, for most people Guattari is still, first and foremost, Gilles Deleuze’s friend. Even the recent shift in Deleuze studies, which has recovered Deleuze from earlier detractors (and some proponents) and repoliticized his work, has continued to leave Guattari out of it. Perhaps the best of these is Andrew Culp’s recent little book Dark Deleuze, which takes Deleuze back from those who saw him as the philosopher of “joyous affirmation” and who experienced his work (without always admitting it) as vitalist, life affirming, and even positive.[2] Instead such readings have shown the “dark side” of Deleuze: his negativity, his resistance to all things celebratory of nature, impulse, and freedom, and ultimately his embrace of “death.” This argument is not just academic bickering about Deleuze but a vital argument about our politics going forward in the technological age. It hinges on the difference between those who continue to seek experiences that are free of or combative against technological power, and those who feel that there is no way back to an untechnological experience, if such a thing ever existed in the first place, and who embrace the kind of death of the human that will be heralded by our becoming machine. Guattari should remain a vital part of this debate.