Old Rags, Some Grand

George M. Cohan’s flag-waving refrains

Scott A. Sandage

“These Colors Don’t Run,” I keep reading. Small wonder, after six months holding on by a thread to a speeding Eddie Bauer Ford Explorer. There used to be some rule about burning a flag when it gets torn or dirty. Does this mean it would be patriotic to torch a sport utility vehicle?

By spring, the flags of September 11 looked like veterans of Ground Zero. Even Presidents’ Day sales could not move overstocks of red, white, and blue stickers, magnets, mugs, and mittens. Twenty-six stripes for the price of thirteen! Patriotism’s pan had flashed. Again.

Up in the Bronx, George M. Cohan turned in his grave, or rather in his tiffany-windowed granite mausoleum at Woodlawn Cemetery—the house that flag-waving built. Let’s hope they buried Broadway’s ur-hoofer in his tap shoes.

Any American who grew up in the twentieth century learned the songs of George M. “I’m a Yankee Doodle Dandy” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag!” rang out at scout jamborees and on fourth-grade field trips to cheer up the nursing home: “Every heart beats time, for the mud, soot, and grime.”

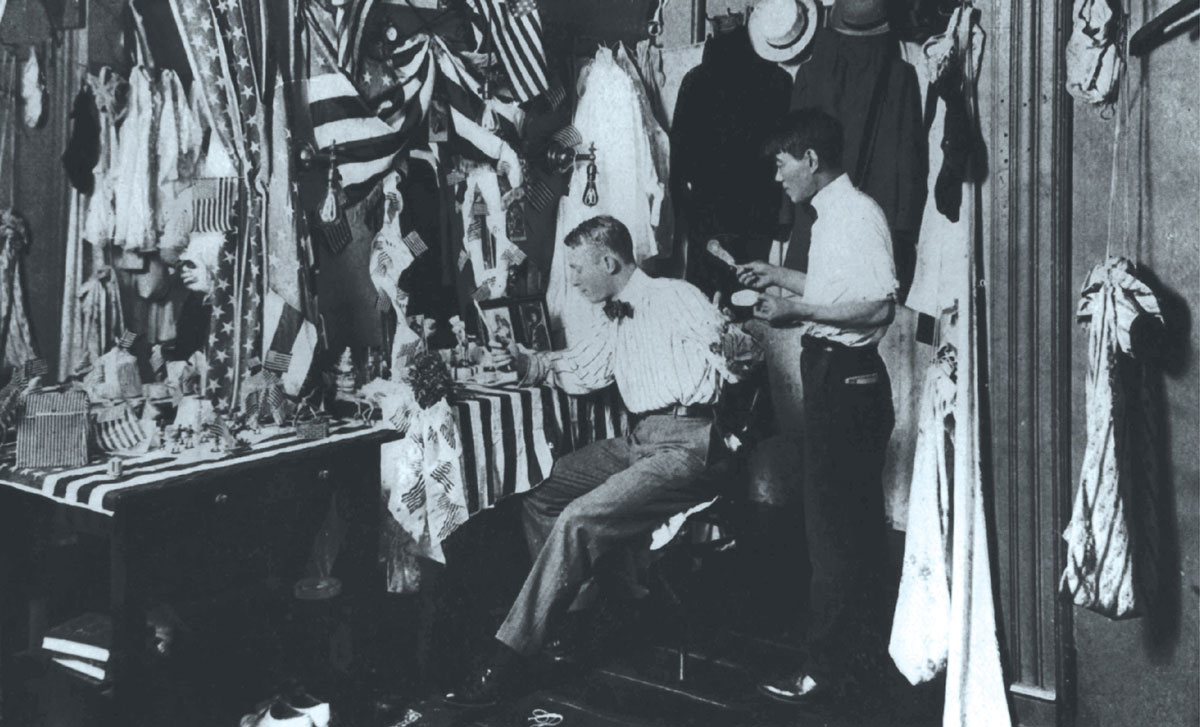

A century ago, Cohan invented patriotism as we know it: loud, brash, mass-market fervor at so much per stripe. Scion of a vaudeville family, he made his Broadway debut in February 1901 in a musical called The Governor’s Son. Fifty-some plays followed over three decades. To approximate his versatility, imagine the talents of Irving Berlin, Neil Simon, Spencer Tracy, Robert Preston, Gene Kelly, Bill Irwin, Groucho Marx, Bob Fosse, Hal Prince, and David Merrick—all in the body of a racehorse jockey. Cohan found major success as a composer, lyricist, playwright, actor (light and dramatic), singer, dancer, clown, comedian, choreographer, director, and producer.

And flag-waver. Yet, commodified patriotism was merely an element in Cohan’s greater invention: American musical comedy. Half a century before Rodgers and Hammerstein got the credit, Cohan used songs and dances to tell integrated stories. His patriotism was sincere, but he also knew how to milk applause. “Many a bum show,” he once said, “was saved by the flag.”

Leave it to Americans to forget the artistic innovation and keep the gimmick. Despite (or because of) tributes by James Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942) and Joel Grey in the 1968 Broadway play George M!, if Cohan is remembered at all, it is as a professional flag-waver. In fact, Cohan’s flag-waving got him in trouble twice—both times prefiguring today’s climate of thug patriotism and constitutional flag-protection amendments.

In 1905, the toast of Broadway was grand marshal of a parade for Civil War veterans. Riding next to a graybeard who cradled a battle-torn flag in his lap, Cohan asked about it. After a few words about Gettysburg, the old soldier looked down and said, “She’s a grand old rag.” With ragtime all the rage, a song called “You’re a Grand Old Rag” seemed just the thing for Cohan’s next musical. Songsheets and Edison cylinder recordings were already on sale when the show (audaciously entitled “George Washington, Jr.”) opened to scandal. The Daughters of the American Revolution (knee-jerk, even then), and blowhards like President Teddy Roosevelt, accused the star of desecration. In a rare retreat for the headstrong showman, Cohan recalled the sheets and cylinders (missing a few that collectors prize today) and rewrote the song into the piece of cheese most of us learned too well. The 1905 incident proved a rule that George M. coined: there’s no such thing as bad publicity. But the events of 1941 ended differently.

At 63, Cohan was battling abdominal cancer. More than ever, he needed the help of his longtime valet, Michio “Mike” Hirano. A Japanese immigrant from Shizuoka Prefecture, he had been the showman’s gatekeeper and confidante for decades. When Hirano was busy, Cohan delighted in answering the telephone in a heavy Japanese accent, to screen his own calls and frustrate the press. George M. even wrote a part for Mike in a 1936 Broadway play. Hirano had only one line, but it stopped the show nightly by breaking Cohan into fits of laughter. By 1941, Hirano enjoyed minor Broadway celebrity as the star’s ever-present sidekick, backstage and at hangouts like the Oak Room at the Plaza (where a bronze plaque still marks Cohan’s secluded corner table).

Soon after Pearl Harbor, Hirano’s visibility caught him in the backlash against Nisei and Issei: immigrants and citizens of Japanese heritage. Intelligence agents pronounced both groups harmless, and not one case of espionage ever stuck. Yet, as Greg Robinson relates in his new book, By Order of the President, Franklin D. Roosevelt imprisoned more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans during the war, in what a classic government euphemism termed “internment camps.”

Cohan tried to rescue Mike. On 18 December 1941, he sent a long, urgent telegram to Attorney General Francis Biddle, writing “I will personally vouch for Mike Hirano.” But this was one string the ailing showman could not pull, despite renewed fame. The war brought his music back in style, after its eclipse by that of Cole Porter and the Gershwins. Franklin D. Roosevelt presented him with a Congressional Gold Medal in a White House meeting that framed James Cagney’s cinematic flashbacks in Yankee Doodle Dandy. Of course, the film did not portray Michio Hirano, not even for one line. Onscreen and in life, Hirano simply vanished. Some said he went into the camps; others, that he escaped to freedom, of a sort, in the sweatshops of wartime New York.

The nation’s preeminent patriot died in November 1942. He lived long enough to watch his life in the movies and to see something more important. With the loss of Mike, Cohan finally made the connection between jingoism and prejudice. “He felt very bad about that,” his son George M. Cohan, Jr., told me in a 1988 interview. Never one for self-criticism, the old flag-waver saw his own hand in Mike’s fate.

The Cohan children had grown up with Hirano and looked for him after the war, but in vain. They hoped he would show up when a statue of George M. was dedicated on Times Square in 1959, but he did not. As late as the 1970s, reported sightings had Mike selling oriental kitsch in Chelsea or upholstering furniture on the Upper West Side.

Cohan’s star still rises during wartime and on his birthday, the Fourth of July, before burning out as quickly as a dime-store sparkler. At less fervent moments, were it not for dinner theaters and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, nobody would remember Cohan at all.

And of course, nobody does remember Michio Hirano. I make an effort to think of him in parking lots and at tollgates, when I see a shredded, sooty flag dangling from a gas-guzzling Leviathan. And I can’t help but think of Mike when today’s Attorney General or some other song-and-dance man uses September 11 to defend ethnic profiling, arbitrary detentions, and invasions of privacy. But I also think of Cohan and wish that he had never rewritten the song we all learned in school: “Should auld acquaintance be forgot, keep your eye on that grand old rag!”

Note: A recording of “You’re a Grand Old Rag” is available on the CD accompanying this issue.

Scott A. Sandage is associate professor in the Department of History at Carnegie Mellon University. His book Forgotten Men: Failure in American Culture, 1819–1893 is forthcoming from Harvard University Press.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.