Welcome to the Molly-House: An Interview with Randolph Trumbach

The gay male subculture of eighteenth-century London

Amanda Bailey and Randolph Trumbach

Randolph Trumbach was the first historian to argue that there was a thriving, gay male subculture in eighteenth-century London. The public life of this subculture revolved around certain coffee-houses or alehouses that catered to so-called “sodomites.” These molly-houses, as they came to be known, provided a protected environment where men could drink, dance, and have sex with one another. While an established molly-house such as Mother Clap’s served as many as forty men on any given night and provided a back room for more illicit activities, a molly-house could be as informal as someone’s private room in an otherwise “straight” public house. Amanda Bailey met with Trumbach to discuss the history of the first gay coffee-houses.

Amanda Bailey: How did your research on molly-houses come about?

Randolph Trumbach: I was actually finishing my thesis on the aristocratic family and looking for material on the history of sexuality. As I started reading eighteenth-century newspapers, I began to see arrests of men in public, in public houses, and so on, and it suddenly struck me that it seemed relatively similar to the Chicago gay male subculture that I was just discovering at that point.

Was this before or after Stonewall?

It was in 1969, the year of Stonewall, that I was doing this research. I was at that point just coming out, and so as I discovered the twentieth-century subculture, I saw something that looked rather like it in the newspapers from the 1720s. I started gathering the material and went on to find evidence of trial accounts, and that’s when I put the newspapers and trial accounts together.

Mother or Margaret Clap’s molly-house, one of the most famous ones—in fact, a play about this particular molly-house (Mother Clap’s Molly House) had a recent run at the Barbican in London—is described by its proprietor as a “coffee-house.” Your research shows that patrons did more than drink coffee at Mother Clap’s.

Coffee-house was a very general term in the eighteenth century. Occasionally, you find a house of female prostitution described as a “coffee-house,” and it is not clear to me whether coffeehouses literally sold coffee as well as alcohol. The all-sodomitical coffee-house or molly-house was a safe space where sodomites could meet. Some molly-houses, though, were extremely simple—for instance, nothing more than somebody’s room where men met each other, in which case the owner of the room would supply containers of ale. In some cases, a molly-house was a room in a standard drinking establishment such as the backroom of a tavern, where men and women of the neighborhood would come to drink.

So there would be patrons who frequented the coffee-house or the tavern who, presumably, had no idea that it was serving multiple functions or multiple populations.

It was possible that if you were a man who was interested in straight young men or boys, you could bring a partner to a house that was otherwise a standard drinking establishment. If, say, you picked up a soldier in the street and brought him back to a standard house—as did Charles Hitchen, the Under Marshall of London—you would rent a private room. If you picked up a teenage boy on the street and brought him back to a tavern, you might discover that what you thought was a secluded corner was not so secluded after all. In fact, it was quite likely in these instances that other customers, men and women who were using the house otherwise, could peer in on your illicit activities, perhaps through a hole in the wall. Meetings in conventional public houses were very risky for this reason, and a meeting in a private space reduced the likelihood that patrons would rush in and arrest you. Those who could not afford to rent a private room could bring soldiers or young boys to a molly-house. Mother Clap’s molly-house, for example, had security at the door to ensure that the men who came in could be vouched for as sodomites.

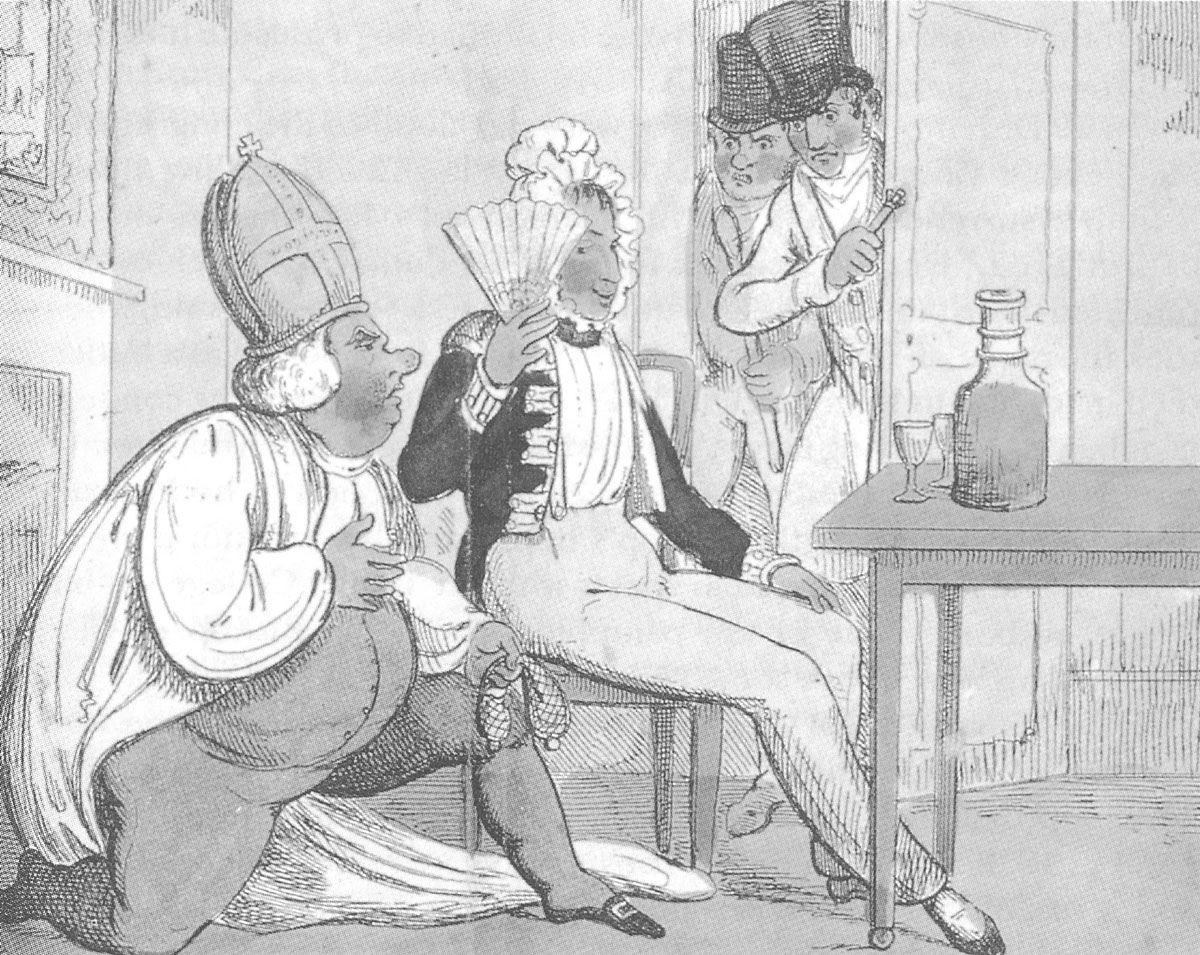

Molly-houses like Clap’s also had backrooms where men went to have sex and this backroom was called the chapel. There are descriptions from eighteenth-century sources of elaborate transvestitism, mock male marriages, and even mock births, in which a molly would deliver a wooden doll that was then baptized. In the molly-house there would typically be a good deal of what we now call “camping.”

Marilyn Monroe I’d understand, but giving birth?

It is interesting that the camp performances in twentieth-century gay clubs and bars focus on men dressing and acting like seductive women, whereas in the eighteenth century the mollies simulated marriage and performed mock births. Mollies even played the roles of the gossips or other women who typically assisted the childbearing “woman.” To understand the difference between eighteenth- and twentieth-century drag, I think we need to understand that the eighteenth century was a period in which love and marriage based upon romantic attraction and the tender care of children was increasingly becoming the standard of family life for all members of the culture. In this period, though, it would have been almost impossible for two unmarried men to set up house together. There are, however, exceptions. French and Dutch sources from the late eighteenth century provide examples of men living together in something like marriage, and in the 1880s one of the male couples in Oscar Wilde’s circle who set up house together went so far as to put on a wedding breakfast. I would presume that mollies were affected by the same desire for domesticity as everyone else, and that the camp performance of having children tells us something about how difficult it was in the eighteenth century for men to live with other men in domestic arrangements.

The word house in molly-house speaks to the need for domesticity, and when we think of domesticity we think of a private and protected domain, but how safe was the molly-house for the men who went there?

The manuscripts document about 17 molly-house raids from 1726 to 1727. Other than the raids of the 1720s, though, the molly-houses were rarely raided. It was difficult for police to get into the houses and if they did, I suspect that they would likely have been met with great resistance. The molly-house was a safe space because, like the brothel for female prostitutes, it provided an enclosed space. Mollies could go to the molly-house to socialize with other mollies, but they could also leave the molly-house and troll the streets for straight boys or soldiers to have sex with, who they then could bring back to the molly-house.

Where does the word molly-house come from? The slang term molly was originally used to refer to a female prostitute in the seventeenth century. Was the molly a particular kind of sodomite?

By the 1750s, the idea of the sodomite as a distinct kind of person was well established. The sodomite-molly in the public’s mind was always going to show some sign of effeminacy. It might have simply been in the way he walked, the way he talked, the way he dressed, with excessive elegance. The idea that one could be recognized by his mannerisms or style of dress is corroborated by reports of people trying to catch someone by running down the street calling, “Stop! A Sodomite! Stop! A Sodomite!” and of a crowd gathering to assist them. There were also some mollies who dressed as women. From what I can tell, in the eighteenth century most of these transvestite mollies were involved in prostitution. Trial accounts suggest that mollies who dressed as women were often very convincing, which, of course, created difficulties for their heterosexual customers.

This notion of types is very interesting because what happens, I would argue, is that in the early eighteenth century the world for the first time splits into a heterosexual majority and a homosexual minority. A world in which men like boys and women is a world that no longer exists after 1700 in Western Europe. One of the last English examples of acceptable bi-sexuality was Lord Rochester, who had female mistresses and a wife but also openly liked boys. In a famous poem he says to one of his female mistresses, “Nor shall our love-fits, Chloris, be forgot, / When each the well-looked link boy strove to enjoy, / And the best was the deciding lot / Whether the boy fucked you, or I the boy.” The world where an adult woman and an adult man share the sexual favors of an adolescent male is one that disappears circa 1700.

As you move into the eighteenth century, sodomitical desire is articulated in three different forms. You have, first of all, the group that likes other sodomites and whose sexual preference is for an attractive male around 20 or 30. You then have a second group made up of those who prefer adolescent males between 15 and 19. Then there is a third group of men who want heterosexual males. These three forms of homosexual or sodomitical desire in the eighteenth century were not yet sharply differentiated in the public mind, but I suspect that it is very likely that this differentiation did exist in the minds of individual sodomites.

It seems that the distinguishing feature of the molly, then, was not so much the age or sexual orientation of his object choice but rather his effeminacy.

The public was convinced that the molly was always easily recognizable by his behavior, dress, or gait. There was, though, a tradition continuing right through the eighteenth century of male foppery in dress, which some other people would look at and say was effeminate.

There is an instructive case from eighteenth-century Paris. Two young Parisian sodomites were mobbed in the street and identified as being effeminate, but their effeminacy became apparent only because they were trying to dress like gentlemen. Apparently, when they adopted a gentlemanly manner, it looked effeminate to the working-class eye in the Parisian street. Upper-class manners, as practiced by aristocrats, were always more elaborate, more formal, and therefore, as in the version practiced by these two men, shaded into effeminacy. Ned Ward, a stout, hardy Englishman from the early eighteenth century, described the male aristocrats whom he observed in the park as faining and submissive and as not properly assertive over the women they were with. To some degree, working-class men tried to use elegance to mask their effeminacy. Sometimes this worked, but sometimes it didn’t.

Upper-class men also attempted to hide behind elegance. There has been a big debate about whether Horace Walpole, the great letter writer, was gay or not. It is clear that Walpole was gay; there is no doubt about it. Both straight men and women instantly spotted Walpole and his circle of friends as gay. In the 1790s, one member of their circle wrote in her diary that Sir Horace Mann, one of Walpole’s correspondents and friends, was “you know, one of the finger twirlers.” There are comments in the appendix of Walpole’s letters that their whole circle was effeminate, but Walpole and his friends are convinced that they could disguise the fact that they were gay by taking on the mask of elegance.

Were men who were “elegant” or extravagantly dressed and who registered as “effeminate” always thought of by the general public as involved in sodomitical activities?

Those who were close enough and in the know could spot the place where one slipped from acceptable heterosexual elegance into the elegance associated with a homosexual coterie. Old-style or aristocratic effeminacy, and new-style, let’s call it sodomitical, effeminacy were not always distinguishable, but I think old-style effeminacy was becoming more and more controversial because if you pushed it just a slight bit, you could say it was really sodomitical.

The word effeminacy in the eighteenth century was still used in its traditional sense of being weak rather than effeminate in the sense of being connected to homosexual desire. I think that the traditional use of effeminacy in the eighteenth century as weak was becoming contaminated, though, by the fact that effeminacy was increasingly tied to the issue of sexual desire exclusively for other males. By the twentieth century, there is a presumption that effeminacy has always been tied to the desire for other males, but in the eighteenth century, the connection between effeminacy and homosexual desire was not as strongly forged.

According to the conventional point of the view, effeminacy, homosexual desire, and sodomitical behavior were inextricably linked, but did mollies themselves understand these terms as mutually implicated?

Some sodomites were trying to avoid effeminacy in their partners. I would speculate that those homosexual men who were more masculine in their behavior tended to prefer adolescent males, because it allowed them to bypass the issue of adult male effeminacy. You can achieve the sexual subordination of a male partner through his age and vulnerability, rather than through his effeminate mannerisms.

So, you find someone like the eighteenth century author William Beckford, one of the wealthiest men in London, who when he was 19 met an extremely beautiful boy of 10. Beckford called the boy, whose real name was William Courtenay, “Kitty,” because he was like a kitty; soft, pretty, and all the rest of it. It then turned out that by the time boy turned 16, when puberty occurs, “Kitty” began to show all the signs of being an effeminate sodomite. Beckford describes these signs of effeminacy in terms of the young man’s taste in clothes. He says, “it’s all balloon hats and silver sashes.” In other words, according to Beckford the young man was dressing so extravagantly and elegantly that he was displaying all the obvious signs of an effeminate sodomite. Beckford was totally turned off. Once it was clear that Kitty had turned into an adult sodomite, Beckford described him as a berdache, that is, a passive sodomite who decks himself out like a milliner’s dummy and paints his face like a whore. Beckford liked young boys because for him they didn’t raise the specter of effeminacy.

Beckford himself, however, is described as singing with a eunuch’s voice. To the outside world, once they knew, or thought that they knew that he was a sodomite, they saw effeminacy in him whether it was there or not, because that was what you were supposed to see.

What about men who frequented the molly-houses? What kind of men would one expect to find there?

You presumably know that you will find males who are primarily interested in other mollies at the molly-house, and, presumably, mollies who like other mollies are attracted to their effeminacy. You are not going to find adolescent boys or straight soldiers there, since these are men one is more likely to pick up on the streets or at the pissing posts and bring back to the molly-house since these men did not see themselves as sodomites.

It seems to me that one way to pursue the history of gay male subcultures in the West is to track the various ways over time that gay men have sexualized public space.

After the 1950s, gay men become identified as the persons who sexualize public space, whether it is bars, parks, or public toilets. But that is a very recent development, because throughout the 18th, 19th, and even the early 20th centuries, heterosexual males were also likely to use the same public spaces—bars, parks, public toilets, darkened streets, theaters—for sex with female prostitutes.

After the 1950s, public sex with female prostitutes declines as a significant form of sexual activity for straight men. It is in this period that there is, what I would argue, the acquisition by heterosexual women of something more like a male heterosexual identity, which grows out of the new freedoms afforded by birth control. Straight men can now have sex with their girlfriends in the privacy of their apartments. After the 1950s, only gay men are left having sex in public places.

How do gay men today use public spaces like cafés, bars, theaters, parks? Do they use these spaces differently than their heterosexual counterparts?

The New York City café seems to have had a revival. You can now certainly have coffee in more places in New York, and you can sit down and socialize. I know that the coffee bars in New York City bookstores have become pick-up places for gay men. I presume the endless number of Starbucks are probably similarly used.

In our era, the use of public space for sex has increasingly declined, and, I suspect, this trend is going to continue. In the eighteenth century, the coffeehouse was the site of pick-up and sexual activity for female prostitutes and for male sodomites. Today, you can still use public space for pick-up, but as gay men become increasingly domesticated—which seems to be the wave of the future—their use of public space for sexual activity rather than for pick-up becomes more and more limited. In this respect, gay men are moving in the direction that heterosexuals have gone.

Randolph Trumbach is a professor of British history at CUNY Baruch. He has published widely on the history of sexuality and queer subcultures in eighteenth-century London.

Amanda Bailey writes about street life, fashion, and sexuality in the early modern period. She is currently completing a book on late sixteenth-century subcultures of style entitled Flaunting It! A Cultural History of Style in the English Renaissance.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.