Goats on Acid

Just say “maaah”

Sasha Archibald

The United States Food and Drug Administration institutionalized laboratory experimentation on animals in 1908. At that time, the FDA’s Drug Division was reorganized into four laboratories, one of which, the Pharmacological Laboratory, stated its purpose as “investigating the physiological effects of drugs on animals.”[1] William Salant, the director of the Laboratory, and Harvey Wiley, the Chief Chemist of the Bureau of Chemistry, shared an interest in the toxicity of caffeine and the rate of its metabolism. Under Salant’s direction, the Pharmacological Laboratory completed several studies investigating the effects of caffeine on rabbits, dogs, cats, frogs, newts, and mice. Salant’s methodology entailed injecting large amounts of caffeine into the thighs of these animals. Following the injection, he recorded the time of death and performed an autopsy.[2] A study of the effect of LSD on an elephant called Tusko done fifty years later in 1962 was hardly more sophisticated. A single intramuscular injection of the highest dose of LSD ever administered to a living being killed the male Asiatic elephant in one hour and forty minutes; after five minutes the animal trumpeted, collapsed, defecated, and began a seizure that continued until its death.[3]

Salant’s work on caffeine was preceded by that of a few other scientists working with animals in the mid-1800s in order to study the effects of morphine, chloral, curara and atoxyl. Nonetheless, the twentieth-century prerogative for animal testing had its impetus in the enormously influential work of the French physiologist Claude Bernard. His seminal work, Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, published in Paris in 1865, affirms the importance of vivisection and laboratory experimentation with animals. Bernard stresses the necessity of using live animals for the advance of science; physiology can only be understood by observation of the living, working inner organism. Animal death is a necessary evil: “To learn how man and animals live, we cannot avoid seeing great numbers of them die, because the mechanisms of life can be unveiled and proved only by the knowledge of the mechanisms of death.”[4]

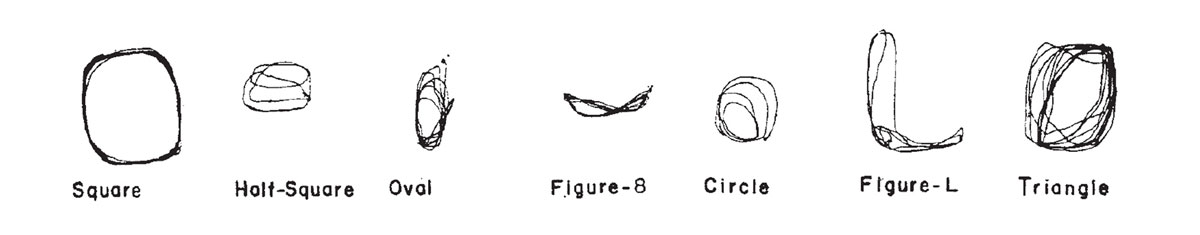

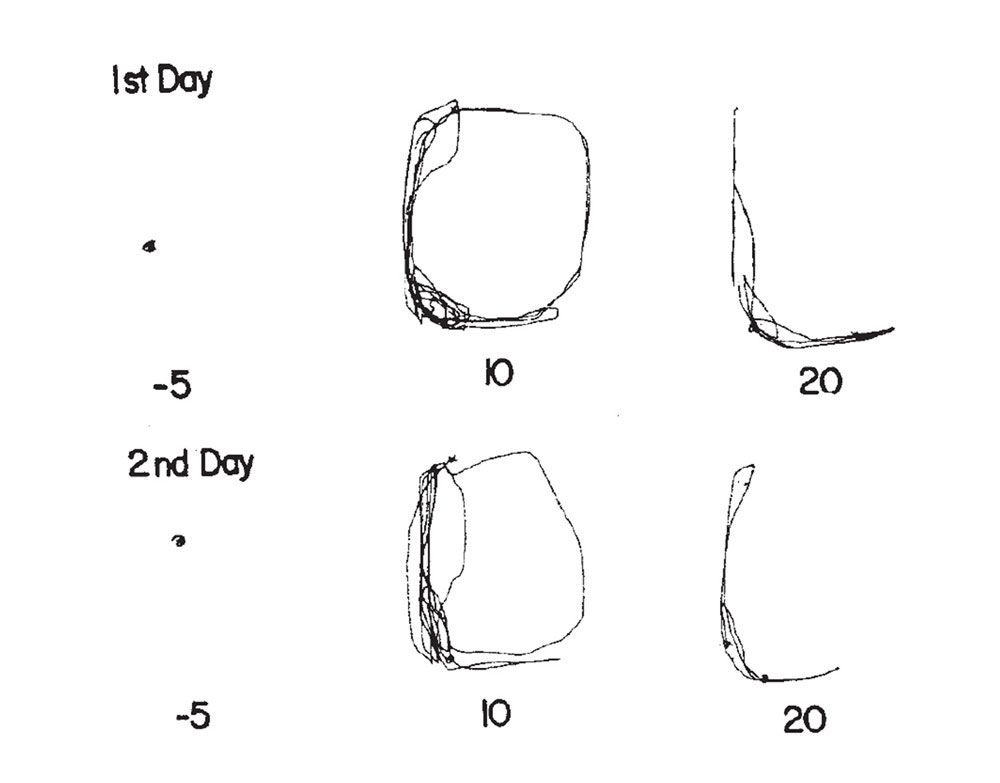

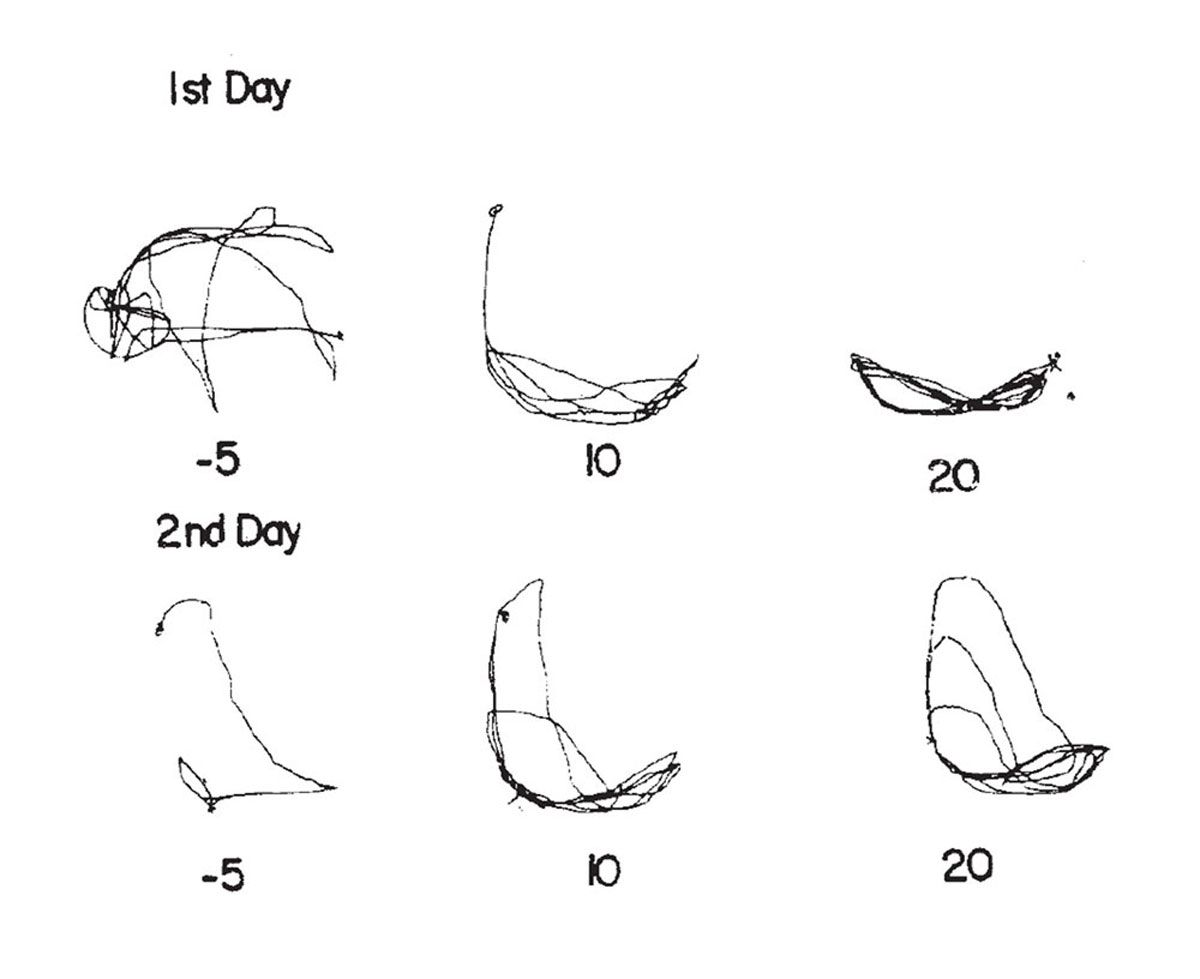

Hallucinogenic drugs were tested on a wide range of animal species in the twentieth century; scientists extensively explored animals’ physiological and behavioral reactions to LSD in particular. Under the influence of LSD, cats, for example, reportedly lose their fear of dogs, bat at the air, and salivate excessively. One LSD-affected baboon or chimpanzee in a group of unaffected animals creates havoc by disregarding the hierarchies of the group. LSD bleaches the skin of newts and toads, causes trout, minnows, goldfish, guppies and Siamese fighting fish to swim in unusual postures, and induces lethargy in hornets.[5] Dolphins become docile and regularize their vocal output at a steady cycle.[6] This last effect may be connected to the finding that affected rats climb a hanging rope at predictable intervals where unaffected rats spontaneously climb.[7] In their study of goats on LSD, Werner P. Koella, Roger F. Beaulieu, and John R. Bergen found that drugged goats walk in predictable geometric patterns, including squares, figure-Ls, and figure-8s. A goat repeatedly induced will always be inclined toward the same pattern.[8] The figures reproduced here show the various geometric shapes of goat walking patterns in response to LSD.

The findings of Koella and his colleagues, like many other investigative studies of animals on drugs, were doomed to obscurity. The results were never taken up in subsequent experiments and each of the scientists quickly moved to different fields of research. Interest in the psycho-therapeutic and potentially utopian possibilities of LSD waned in the 1970s and funding was redirected toward more fashionable drugs.

- Donna Hamilton, “A Brief History of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research,” available here. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- William Salant and J. P. Reiger, “The Toxicity of Caffeine: An Experimental Study on Different Species of Animals,” United States Bureau of Chemistry Bulletin, no. 148 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912).

- L. J. West, C. M. Pierce, and W. D. Thomas, Science, no. 138 (1962), pp. 1100–1102.

- Claude Bernard, An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, trans. Henry Copley Greene (New York: Dover Publications Inc, 1957), p. 99.

- Peter N. Witt, “Effects on Insects and Lower Organisms,” in D. V. Siva Sanka, ed., LSD: A Total Study (Westbury, NY: PJD Publications, 1975).

- John C. Lilly, “Dolphin-Human Relation and LSD 25,” in Harold A. Abramson, ed., The Use of LSD in Psychotheraphy and Alcoholism (New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1967).

- Witt, “Effects on Insects,” p. 467.

- Werner P. Koella, Roger F. Beaulieu, and John R. Bergen, “Stereotyped Behavior and Cyclic Changes in Response Produced by LSD in Goats,” International Journal of Neuropharmacology, no. 3 (1964), pp. 397–403.

Sasha Archibald is a graduate student at New York University and lives in Brooklyn. She is a research assistant at Cabinet.