Some Relics of Childhood

Early works by Auden, Isherwood, Kerouac, Plath, and Shelley

Rodney Phillips

Saved by mothers, fathers, siblings, teachers, and by accident, the letters of children are ubiquitous and almost never interesting. Never, that is unless the child evolved into an adult of genius. Then they seem endlessly fascinating, immediately attractive documents, predicative of the future and redolent with the talent that was to be, or poignant indicators of later tragedy or psychopathology. Paper relics, they sometimes hold an almost holy remembrance of golden ages, better times, funnier faces. “Let each child have that’s in our care/ as much neurosis as the child can bear,” quipped W. H. Auden, who as a wistful grownup was always conscious of his happier childhood as a sort of Eden in limestone. Baudelaire, of course, felt that “genius is no more than childhood recaptured at will, childhood equipped now with man’s physical means to express itself.” Others would look at the relationship between childhood and art (drawing, writing, painting, etc.) as less useful, or even entirely hindering. Samuel Butler, in his appropriately titled The Way of All Flesh, was extreme in his association of childhood with the less-than-perfect: “Could any death be so horrible as birth? Or any decrepitude so awful as childhood in a happy united God-fearing family?” In equally merry misanthropy 300 years later, Dorothy Parker exclaimed: “All those writers who write about their childhood! Gentle God, if I wrote about mine you wouldn’t sit in the same room with me.” In any case, writing and childhood seem inevitably entwined, arising from a common source, which is not quite the same as believing everything is everything. It is much more hopeful.

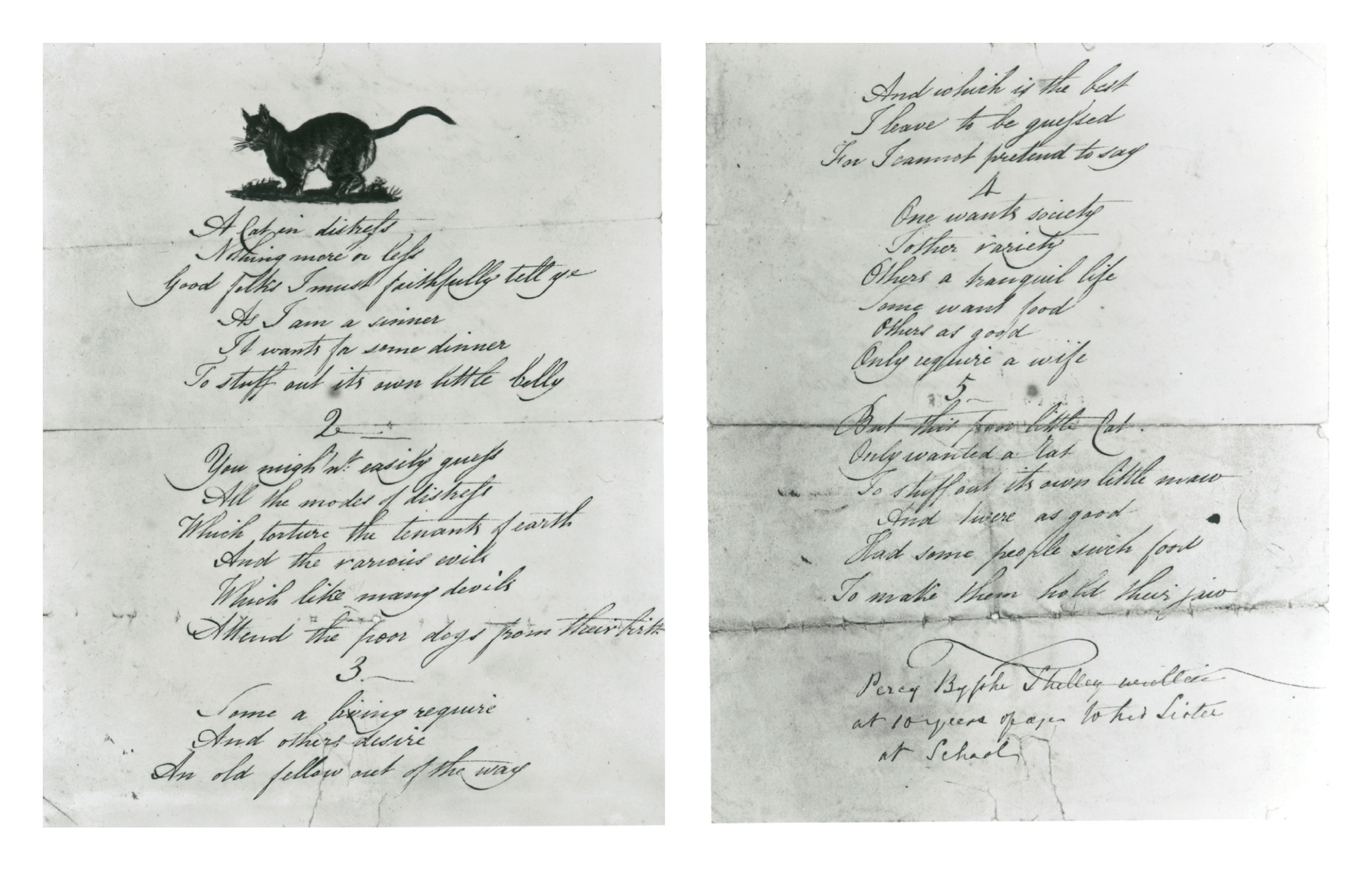

There is probably no more perfect specimen of all this than the child/poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who was indeed a privileged example of both conditions, being the only male among five offspring of Sir Timothy and Elizabeth Shelley, newly wealthy Sussex landowners. Some might claim that Shelley remained a child until his early, tragic death by drowning at age 30. And there are many who would aver that this is a good thing (remaining a child, not dying) and the source of his powerfully affecting art.

The earliest surviving poetry by Shelley is a piece entitled “A Cat in Distress,” written, according to a note on the extant manuscript (penned by his sister Elizabeth), at “10 years of age.” Elizabeth, who would have been eight at the time, drew the illustrating cat as well. The poem comes down to us through a younger sister, Hellen, who described it in a letter to Thomas J. Hogg, Shelley’s friend and early biographer: “I have in my possession a very early effusion of Bysshe’s, with a cat painted on the top of the sheet, I will try and find it: but there is not promise of future excellence in the lines, the versification is defective.” Perhaps, but there is evidence of the themes and variations of his later work, including a somewhat imperious, radical concern with the welfare of the local tenant farmers. The young poet’s interest in the fauna of the country estate is reflected, as are his budding republican feelings.

That this poem was addressed to one sister who copied it in order to give the copy to another sister not only adds charm to the document, but is representative of the of the close-knit family of siblings, of whom Shelley was the oldest. In fact, before the age of 10, when he was sent to a boys’ school at Syon House Academy, Shelley was exclusively in the company of women, in particular his adoring sisters who (like his wife Mary afterward), occasionally collaborated with Shelley on his projects. Elizabeth was the Cazire of the book they published together in 1810, at ages 18 and 16, Original Poetry by Victor and Cazire. Amusements of the young Shelleys included storytelling and ritual fires for ghost summoning. Shelley was also given to using his sisters in a variety of “scientific experiments,” including curing them of colds and flu by passing electricity through their bodies. (Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was inspired, in part, by a parallel interest in galvanism.) In his later years, this prodigy of freethinking was given to writing “democrat, great lover of mankind and atheist” after his name on hotel ledgers.

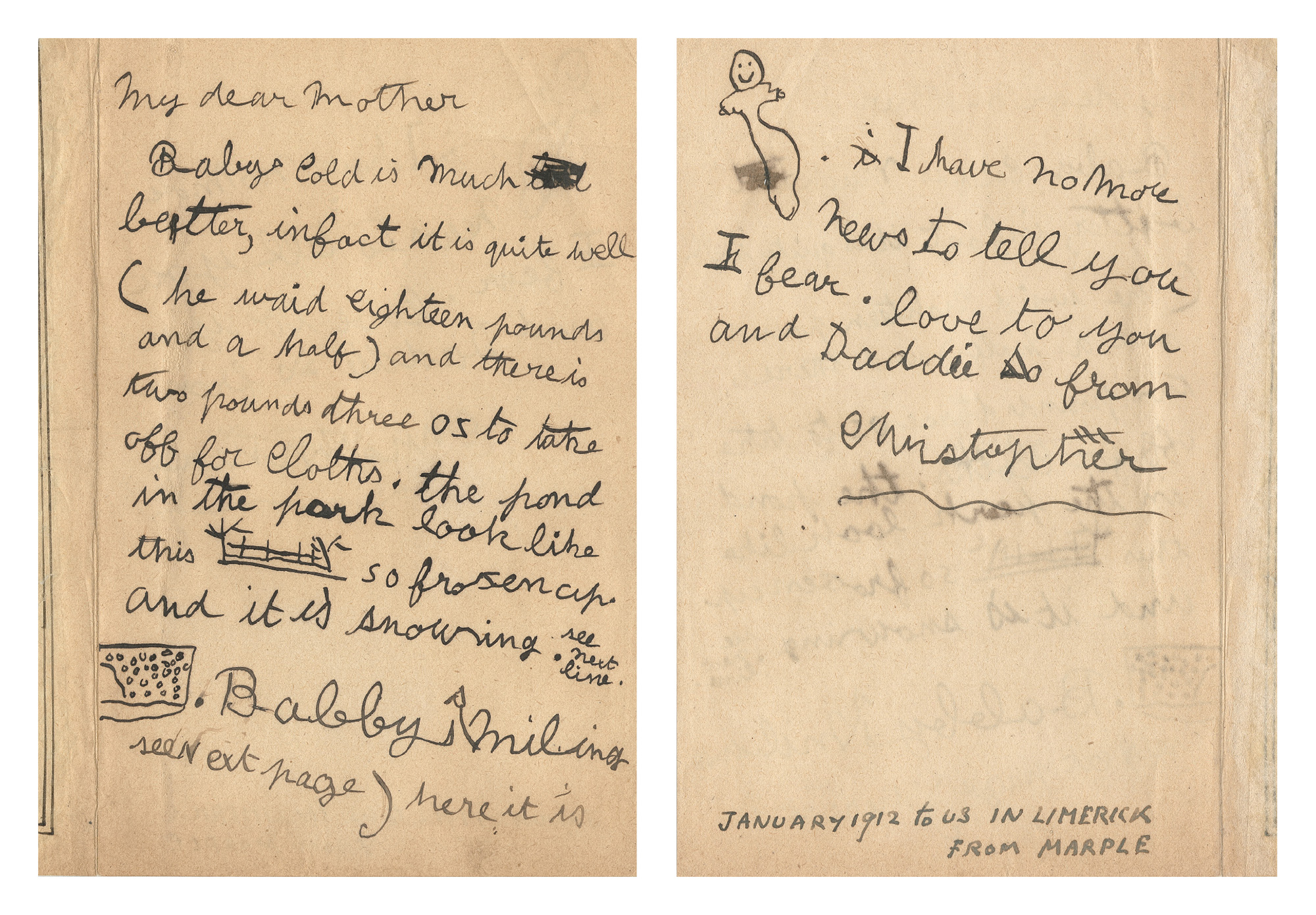

It’s not a great leap from Shelley to Christopher Isherwood, as Isherwood’s childhood was in many ways similar to Shelley’s, including adoring parents, an Elizabethan mansion, and education at elite boarding schools. Like Shelley’s, Isherwood’s childhood was beset by visitations of ghostly figures and a secret, haunted attic. Perhaps this explains the eerie drawing of his baby brother, Richard, in Christopher’s letter of January 1912 to his mother. The eight-year-old was writing from Marple, his grandparents’ estate, where at least two of his early visions occurred. His landscapes of the frozen park are smartly, if a little dissonantly placed to liven up the letter to his mother, who was presumably visiting Isherwood’s father at the military base in Ireland where the family was soon to move. In 1914, Christopher left Ireland to attend St. Edmunds Preparatory School in Surrey, where the next year he met the “grubby” Wystan Auden.

For his part, the young W. H. Auden was an inveterate rambler and hiker in the landscapes of Surrey. In any number of photographs of the young Auden and his brother, they are posed in a field, near a tree, beside a cliff or in another natural environment. Auden’s childhood was, like Isherwood’s, generally happy, and included a mother who kept journals and notes about her children. She was a great encourager of her son, writing down his first “works” (The Adventures of a Daddie and Mummie: I and II) for him when he was four and five years old. In another journal, written in the spring of 1917 on a trip to the Isle of Wright with her two sons, Constance Rosalie Bicknell Auden has pasted her handmade “Programme for a Grand Concert.” on 24 April 1917. The program includes a series of piano works, played by the ten-year-old Auden, and several duets with his mother. The earliest extant piece of Auden’s writing is also in the same notebook.

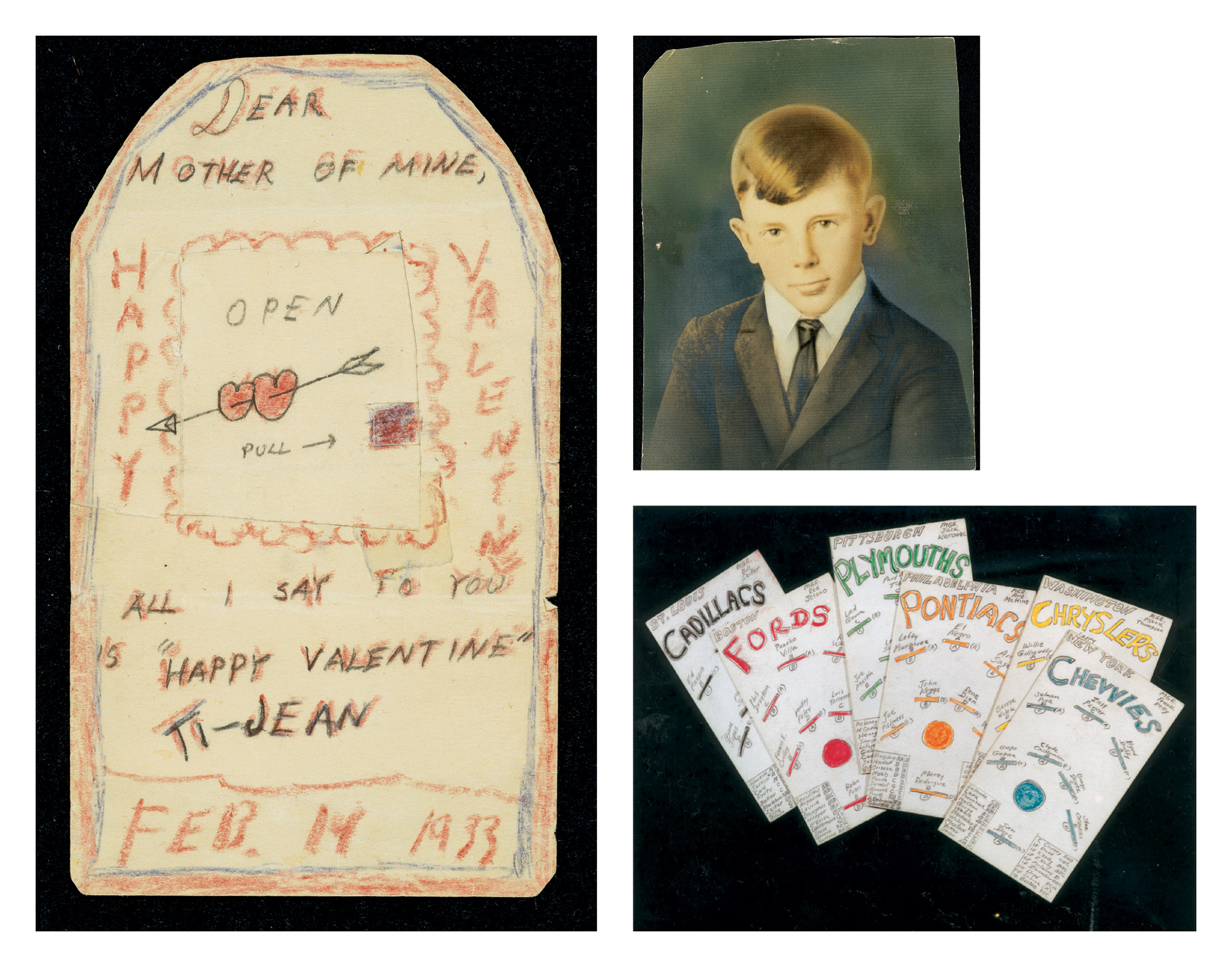

On another plane altogether, the childhood of Jean-Louis “Ti Jean” Kerouac in Lowell, Massachusetts seems gruesomely American. The child of French-Canadians Leo and Gabrielle Kerouac, his upbringing was strictly working class. Kerouac wrote his first “novel” at age 11, probably in February 1933. He also created horse-racing newspapers and a complex group of records and statistics surrounding his own fantasy baseball league.

Obsessively devoted to his mother, to whom he sent many handmade valentines, Kerouac describes his relationship with her and his brother in the introduction to Lonesome Traveler, a collection of road-trip related pieces: “Influenced by older brother Gerard Kerouac who died at age 9 in 1926 when I was 4, was great painter and drawer in childhood (he was)—(also said to be saint by nuns)—(recorded in novel Visions of Gerard).—My father was completely honest man full of gaiety; soured in last years over Roosevelt and World War II and died of cancer of the spleen.—Mother still living, I live with her a kind of monastic life that has enabled me to write as much as I did.”

The earliest surviving example of his writing is a crayon valentine to his mother, February 14, 1933. He was 11, the age at which he wrote his first “novel.” He also created horse-racing newspapers and a complex collection of records surrounding his own fantasy baseball league. These include a group of team cards, drawn in pencil and colored pencil on paper sometime in 1936. Kerouac was 14 when he created these cards, but had been playing the game for years, and was to play it until the end of his life. The names of the players, like those of the teams, appear to be fictional—except for Pancho Villa, whom Kerouac placed on the Boston Fords in center field. His story about a rookie pitcher, “Ronnie on the Mound,” which appeared in Esquire in May of 1958, even included names of fantasy baseball league players and managers.

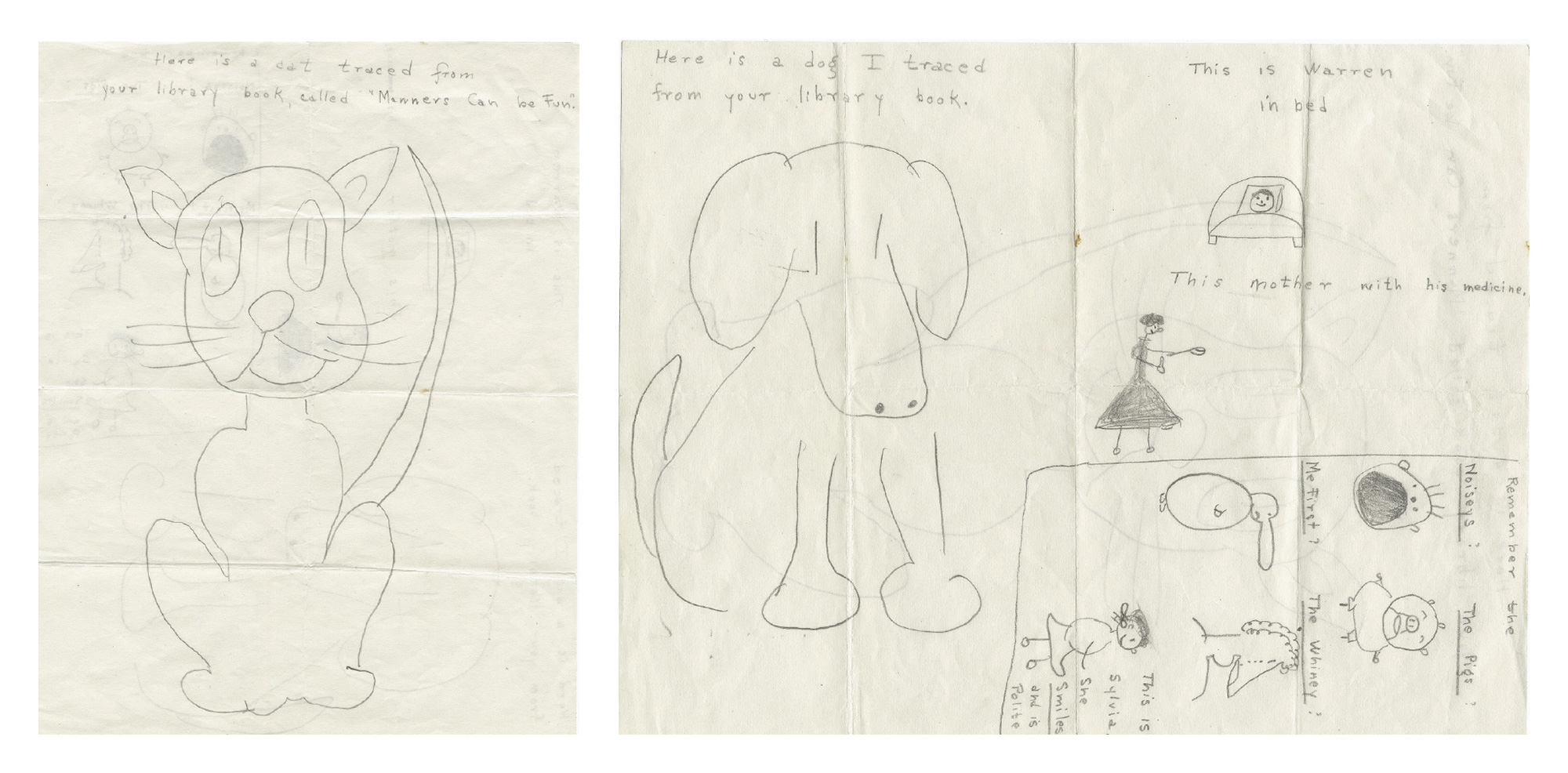

Kerouac’s obsession with the Fords and Cadillacs seems to fit his literary personality, but it is hard to imagine Sylvia Plath as a child drawing large cats. The cat and dog she drew (at an age between 10 and 12) for her brother Warren, who was apparently sick in bed, seem neither comforting nor comfortable. On the other hand, there is ironic awareness in her self-caricature as one who “smiles and is polite.” She was at this point, still the perfect A student and perfect daughter, despite that her father’s death in October of 1940 must have nearly destroyed her childhood world, transmuting her early years into a “beautiful, inaccessible, obsolete, a fine white flying myth.” This drawing was made sometime during the period when the Plath family lived in Wellesley, probably the most difficult time of Sylvia’s childhood. Her mother had her put back a grade, believing that she didn’t make friends easily and was too intense in her studies. Of course the five-foot-nine-inch fifth grader was taller than most of the boys in her class, and she went on to a triumphant series of accomplishments during her years at Philips Junior High School and Bradford High School. But the neurotic child remained, to reach her apotheosis as Ariel.

Sources

W. H. Auden, “Letter to Lord Byron,” The English Auden: Poems, Essays, and Dramatic Writings, 1927–1939 (New York: Random House, 1978).

Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life,” section 3, L’Art Romantique (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1885).

Samuel Butler, The Way of All Flesh, first published 1903, (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1964).

Thomas Jefferson Hogg, The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley (London: Edward Moxon, 1858).

Jack Kerouac, Lonesome Traveller (New York: Grove/Atlantic, 1972).

Dorothy Parker, interview in Writers at Work, First Series, ed. Malcolm Cowley (New York: Paris Review, 1958).

Sylvia Plath, “Ocean 1212-W,” 1962, first published in Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams (London: Faber and Faber, 1977).

Rodney Phillips is director of humanities and social sciences at the New York Public Library. He is the author, with Steve Clay, of A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980 (Granary Books/NYPL, 1998), and his chapbook of poems, made in collaboration with the painter John Jurayj, has just been released by Granary Books. His poems have appeared in numerous journals, including the Paris Review and Fence. He lives in New York City.