Ingestion / Culinary Landscapes

Antonin Carême, the Palladio of cuisine

Allen S. Weiss

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

One of the seminal texts in the history of European landscape architecture is the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili of Francesco Colonna, published in Venice in 1499. The tale consists of the phantasmatic quest of Poliphilus, presented as an initiatory drama couched in the form of a dream, recounting his experiences and tribulations as he searches for his beloved Polia. Beginning in the anguished solitude of a wild, dark, labyrinthine forest, he finally emerges, by invoking divine guidance, into a beautiful, sunny landscape of absolute perfection. Here he discovers a scene filled with gardens and palaces, containing enigmatic and emblematic monumental sculptures and ruins representing the arts of the ancient cultures of Egypt, Greece, and Rome, such as pyramids, obelisks, and temples, all evincing a perfection lost in the contemporary epoch. The archaic is brought into the service of the arcane. The allegory then thickens as Poliphilus continues his neo-Platonic quest toward love and truth, encountering five girls representing the five senses, a queen symbolizing free will, and finally two young women symbolizing reason and volition. After visiting the palace, he is taken to the three palace gardens, which are the ultimate expressions of human artifice: gardens of glass, silk, and gold. The craftsmanship was truly marvelous: “All along the walls were flower-beds in the form of tubs, in which were planted a mix of box-trees and cypress, one cypress between two box-trees, the trunks and branches of solid gold, and the leaves of glass so perfectly imitated that one would have taken them for natural. [...] There were also herbs and flowers of diverse colors, forms and species, all made of glass, all perfectly resembling the originals.”[1] The brilliance and genius of this pure artifice incite Poliphilus’s admiration and wonder; mimesis is revealed for its inherent artificiality. This imaginary garden of glass established a major aesthetic sensibility, serving as a model for the interweaving of two arts that had only recently received their muses: landscape architecture and cuisine. For while such a garden of spun glass might never have actually been created, the history of cuisine attests to its influence in the fabulous inventions of pièces montées of spun sugar, pastry, and candy which evoke such fragile fantasy worlds.[2]

Culinary history abounds in examples of such constructions, even predating Colonna. We might recall the details of a great feast given by Amédée VIII, Duc de Savoie, as recounted in the 1420 manuscript dictated by his chef de cuisine, Maître Chiquart. The meal was an amazing spectacle, with the main course presenting a centerpiece formed by a miniature castle with a fountain of Love spouting rose water and white wine at the center of the courtyard, and a different dish at the foot of each tower. Every animal was highly decorated and spitting fire: a huge gilded boar, ornamented with the guests’ coats of arms; a suckling pig; a roast swan, replumed with its own feathers; and, there was, as described in detail, a huge pike cooked in three manners, the tail end fried, the middle boiled, and the head roasted, served with three different sauces. This dish, as well as the centerpiece that adorns the table, constitutes both a secular feast and a cosmic symbol, synthesizing incompatible victuals, contradictory modes of cooking, and heterogeneous symbols into a flamboyant totality. The taste for miracles and marvels certainly does not avoid its culinary instances, though one might suspect that the pleasures of mirabile dictu far surpassed, in many such cases, those of the palate.

Very often, the visual aspect of a pièce montée surpasses the gastronomic value of the dish itself, however antithetical this might seem regarding the gustatory goals of cuisine. For the most celebrated of French chefs, Antonin Carême (1783-1833), the decorative values of cuisine always existed on an equal level with its gustatory qualities. Indeed, Carême’s decorative perfectionism often transcended his culinary aspirations, as when he created pièces montées using inedible binding materials to guarantee their longevity; or even more radically, as expressed in the avertissement to the third edition of his Le Pâtissier Pittoresque, he notes the extent of his passion for architecture per se: “I would have ceased being a pastry-chef, had I blindly abandoned myself to my natural taste for the picturesque genre, such as I conceived it for the embellishment of princes’ parks and private gardens.” This architect manqué would sublimate his untried passion into the some of the greatest manifestations of spun sugar edifices in the history of French cuisine. Consider, for example, his extraordinary “moss-decorated grotto,” described in Le Pâtissier Parisien: “The effect of this large centerpiece is very picturesque. It is round in shape and has four arcades. It is made of hard sweetmeat à la reine, which must also be glazed: one part with rose-colored sugar, one with caramelized sugar, and the rest with lump sugar to which you add saffron; but in removing the hard sweetmeats from the saucepan, you form groups from five to eight and from ten to twelve, over which you sprinkle coarse sugar and chopped pistachios. The rock forms four arcades, which are made up of ring biscuits of almond puff pastry (which you powder with fine sugar sifted through silk). You simply line up these ring biscuits without attaching them at the vertical joints, which in no time produces a nice ridge of rocks. You surround it with meringues glazed and garnished with vanilla cream. The pedestal is made of German waffles; the garnish is Genoese pastries in rings, studded with sugar pearls. The bower is crowned with a small waterfall in silvery spun sugar.”[3] This miniature landscape certainly bears comparison with the Grotte de Thétis in the gardens of Versailles, or the blue grotto at Linderhof created for the mad King Ludwig of Bavaria.

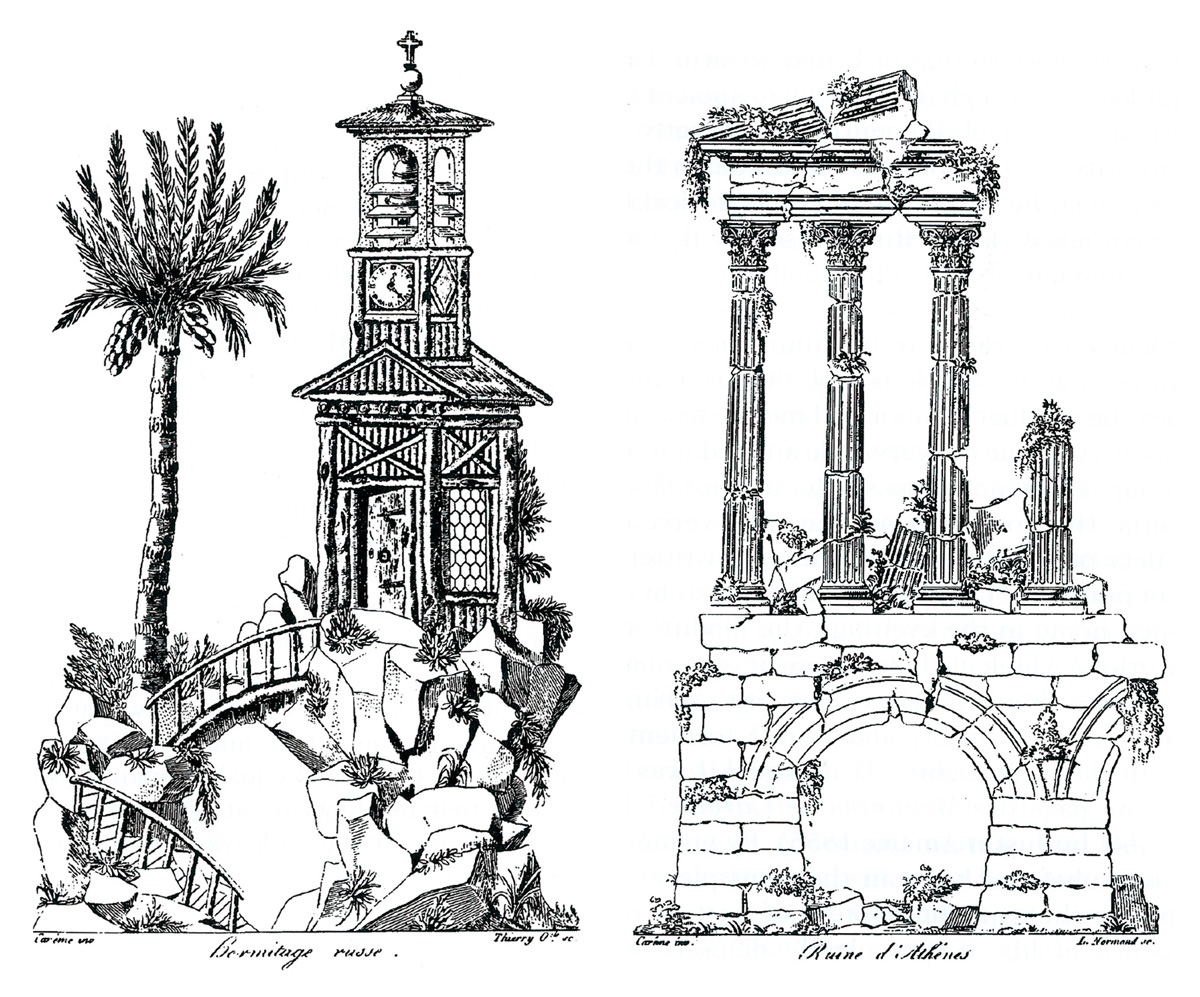

Carême, the architectural autodidact whom one gastronome referred to as “the Palladio of cuisine,” spent untold hours studying drawing, architecture, and garden design (notably works on garden folies) at the cabinet des estampes of the Bibliothèque Nationale (Royale) in Paris. This is attested to by his volumes Le Pâtissier Pittoresque (1815) and Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien (1815), where it is evident that his inspiration was both classical and romantic, though his classicism syncretically responded to the aesthetics of many civilizations. His spun sugar creations in the forms of pavilions, rotundas, temples, towers, fortresses, mills, hermitages, and ruins of all sorts, were created in a great diversity of styles: Italian, Turkish, Islamic, Russian, Polish, Venetian, Chinese, Irish, Gallic, Egyptian, and so forth. All this was finally combined in an imaginative mélange whose results would transgress the historical limits of both architecture and cuisine. This conflation of styles and epochs is, in the case of both landscape architect and pastry chef, a fantasized, stylized reduction of historical detail to imaginative decorative fancy.

The extreme instance of this architectural passion was not, however, restricted to the art of pastry making. Between 1821 and 1826 he published Projets d’Architecture, which included projects designed for the embellishment of both Paris and Saint Petersburg. For example, he proposed, for the place du Carrousel in Paris, a temple dedicated to glory of the French nation, which would display 48 lions’ heads, 12 trophies, 8 statues, and a pantheon of the names of the country’s great heroes. In fact, these projects are as much in keeping with the utopian architectural fantasies of Boullée, Ledoux, and Lequeue as they are with the art of pastry decoration. The actual gardens of the 18th and 19th century offered precisely the sorts of folies, pagodas, gazebos, kiosks, pavilions, belvederes, temples and minarets that inspired the books and the pièces montées of Carême. And yet, however fantastic these projects may seem, Carême’s books remain practical guides to pièces montées, one which, it is hoped, may inspire some readers to create their own contemporary follies.

A striking example of such architectural fantasy reveals a strange modernity at the core of Carême’s classicism, one based on a curious hybrid of styles, materials and natural orders. In a dreamlike evocation, he describes, in Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien, pièces montées that would represent rivers, cascades, and the waves of the sea. This might be compared with another fantasy of edible architecture, eccentric and fascinating, from a text by Salvador Dali, “De la beauté terrifiante et comestible de l’architecture modern style,” which celebrates the oneiric and troubling nature of certain architectural creations, stressing an inexorable desire to “to eat the object of desire.” Specifically, describing two Art Nouveau houses that Gaudi designed on the Paseo de Gracia in Barcelona, he explains how one was inspired by the ocean’s waves during a tempest, and the other by the tranquil waters of a lake. “These are real buildings, veritable sculptures of the reflections of crepuscular clouds in water, made possible by recourse to an immense and mad, multicolored and gleaming mosaic of the pointillist iridescence from which emerge forms of poured water, forms of spreading water, forms of stagnant water, forms of mirroring water, forms of water curled by the wind, all these forms of water constellated in an asymmetric and dynamic-instantaneous succession of bicyncopated, interlaced reliefs, melted by the ‘naturalist-stylized’ nunuphars and nympheas concretized in impure and annihilating excentric convergences, thick protuberances of fear bursting from the incredible facade, simultaneously twisted by all the insane suffering and by all the latent and infinitesimally soft calmness equaled only by that of the horrifying ripe and apotheosic flakes ready to be eaten with a spoon—with the bloody, greasy, soft spoon of gamey meat that approaches.”[4] However surreal and nightmarish, this passage is an archetypally modernist continuation of the imaginary conflation of architecture and cuisine. In this context, we might note that, as befits his art, never does Carême actually describe the state of his pièces montées after the meal is finished, veritable ruins of ruins! For to do so would be tantamount to admitting the temporal and fragile nature of his art, as well as the inexorably mortal side of cuisine. One cannot help but remember the outstanding role of the table, often depicted in a state of extreme chaos, in pictorial representations of vanitas.

- Translated from Francesco Colonna, Le Songe de Poliphile (Venice 1499; Paris, 1546; Reprint: Paris, Imprimerie Nationale Éditions, 1994), edited and prefaced by Gilles Polizzi; 120. See Allen S. Weiss, “Syncretism and Style,” in Unnatural Horizons: Paradox and Contradiction in Landscape Architecture (New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), pp. 9–42.

- There exists a small museum of spun-sugar art attached to a restaurant, Le Grand Écuyer, in Cordes-sur-ciel (Tarn, France).

- Antonin Carême, Le Pâtissier Royal Parisien (1815), cited in Jean-Claude Bonnet, “Carême, or the Last Sparks of Decorative Cuisine,” trans. Sophie Hawkes, in Allen S. Weiss, ed., Taste, Nostalgia (New York, Lusitania, 1997), pp. 176-77. Bonnet’s article is an excellent introduction to Carême.

- Salvador Dali, “De la beauté terrifiante et comestible de l’architecture modern style,” Minotaure, no. 3–4 (1933), p. 74.

Allen S. Weiss has been working hard on ingestion: he recently co-edited French Food (Routledge), and his Feast and Folly is forthcoming (SUNY).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.