The Bull Rider and the Ballerina

Toward a taxonomy of falling

Mary Walling Blackburn

In 1810, Heinrich von Kleist, a pre-eminent German Romantic and melancholic by nature, wrote On the Marionette Theatre, a seminal text on how gravity and consciousness can bungle the grace of the body. According to Kleist, dancers labor against gravity’s force, believing that it is possible to attain a state of grace through their movements by eliminating the combined weight of consciousness and physics. Yet Kleist held little stock in the abilities of the skin-and-bone body and posited that, perhaps, the marionette was a more proper template for “proportion, flexibility, and lightness.”[1] For Kleist, one of the few viable paths to a state of grace appeared “most purely in that human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or the God.” Yet, to be suspended between the two proved unbearable. A year later, he and a married young society lady with terminal ovarian cancer checked into a hotel by a small lake, went over a hill, and had tea. Then, as agreed previously, Kleist shot Henriette Vogel in the chest and then himself in the mouth.

To intellectually give up on the body and simply choose to end its labor is qualitatively and politically different than having a body give up on you. I come from a family where labor exhausts the body before the intellect does. The pleasures and privileges of Kleist’s existential torture are foreign to my kin, who replace theoretical gabbing about motion’s relationship to sorrow with narratives of grief. In other words, my mother’s family was too poor for therapy, pharmaceuticals, or academic pontification—that is, they could not afford the treatments for the human preoccupation with heaviness. A homemade grace and redemption was concocted with the body.

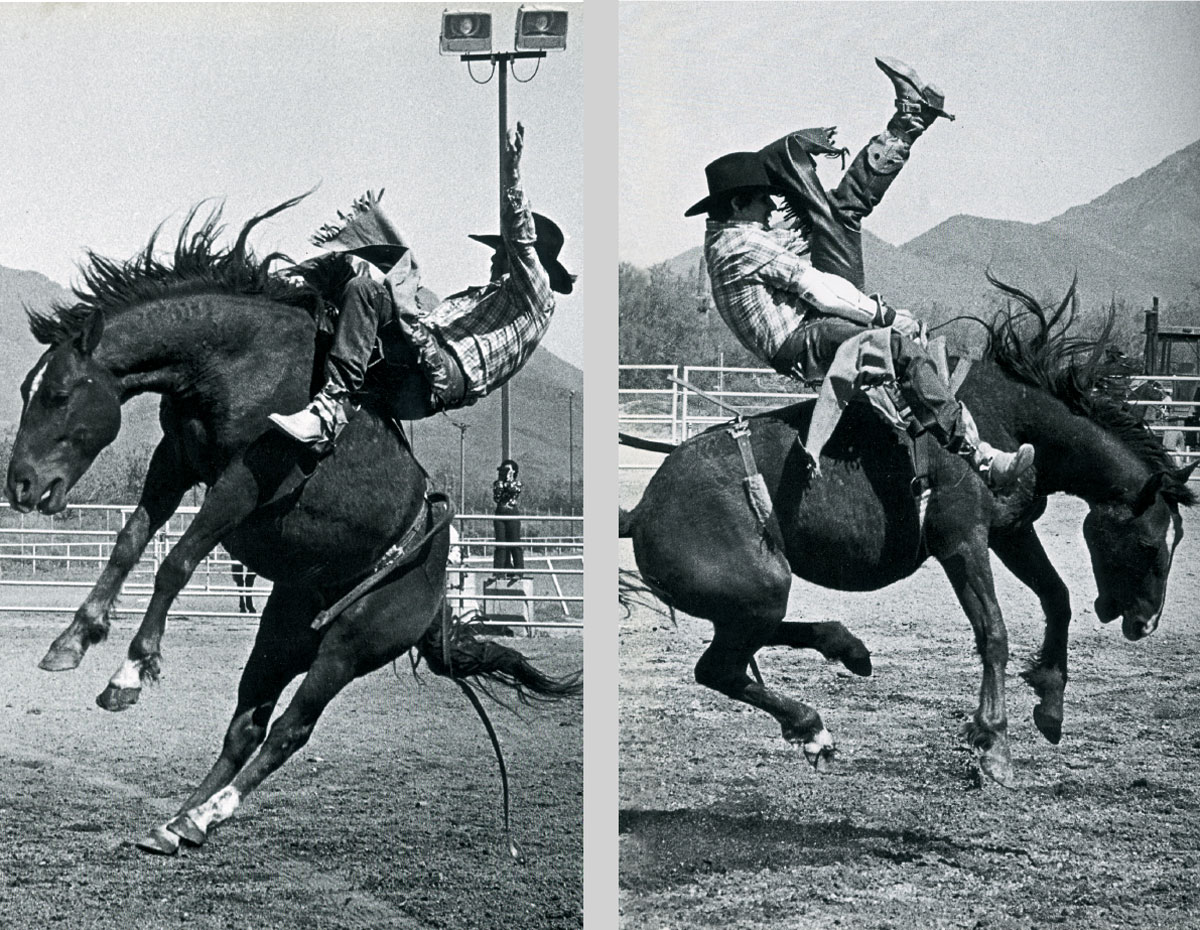

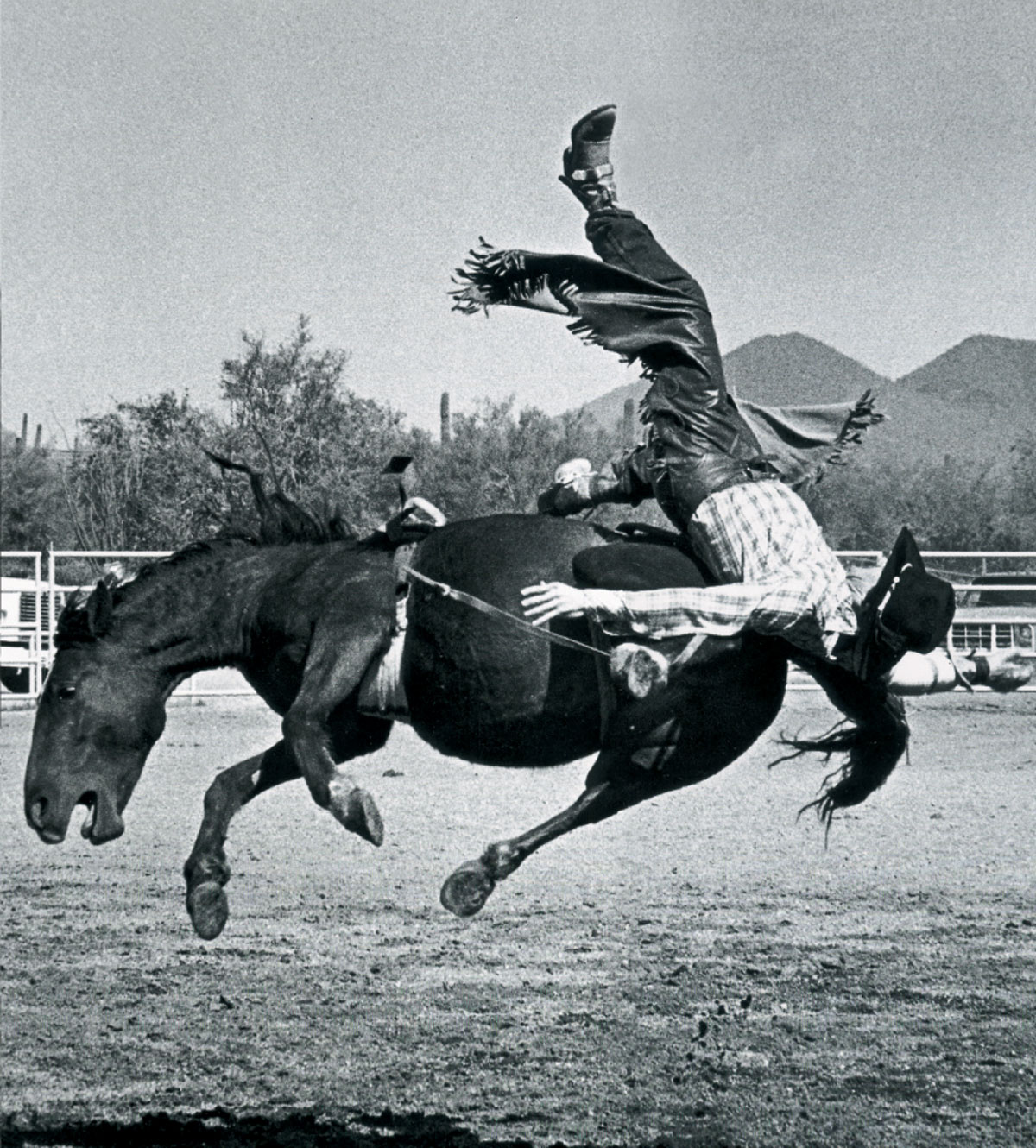

My mother’s father was a bull rider and a bronc buster, and in my family his body is often described as beautiful. With his slow long lope and his fancy-shirted cowboy torso, his body was beautiful from labor (read: ranch work) and broken by leisure made into labor (read: the work of the ranch made into the antics of rodeo). The nervous energy and despair that characterized his untreated manic depression can be likened to vertigo’s alternating sensations of falling and flying. He self-medicated by drinking and by beating the many women who fell in love with him; by throwing his body away and away again, in the forgetfulness and grace of being at the mercy of another animal’s body, be it bull or horse, and by having another human’s body at his will, be it woman beneath him or bar brawler beside him. And in these moments, how does one determine which body is falling and which is flying, which is crushed and which is crushing? What is the choreography of release?

Kleist’s favored false body, the gravity-free marionette, is ultimately alien in a wooden performance dictated by the flesh of another. It fails to provide a model that offers a physical and intellectual reconciliation with our workaday crises. The classical dancer, whose physical iterations of ontological floundering have at least some trace of the human, provides a more recognizable form. Generally, the classical dancer was exhorted to pretend that the earth did not exist, or in the words of Kleist, to believe “the force which raises them into the air is greater than the one which draws them to the ground.” In the early 1700s, the heels were shorn off classical court dancing shoes, after danse basse enthusiast Marie Ann Cupis de Camargo decided that a heel-less shoe would improve the fetterless leap and the airborne arch, as well as help her to better her dancing rival, Marie Salle. By 1832, Marie Taglioni was the first major ballerina to dance en pointe. She was generally credited with the development of this technique, which hastened the proliferation of endlessly elevated arabesques. Supposedly, this cobbled lightness and grace inspired certain Russian fans to douse her old slippers with a sauce and consume them. Bodies broke in the process of shucking off gravity, yet the illusion of flying prevailed. The ballerina pretends that the twenty-six bones in her foot have evaporated or that, at the least, they are exempt from the impact of banging into the earth at high speeds and odd angles.

However, there is something precious and doubly alienating in the lauding of the ballerina as a contemporary vehicle for release from the discomfort of existence. The middle-class aspirations and “high feminine” regulations of the art form conjure weird associations of reptilian thinness, feminine deodorant spray, and middle school bitchiness. Perhaps I reveal myself too much here: a failed child ballerina, the granddaughter of a bull rider, a prep school graduate, a recipient of government cheese—in short, when it comes to class-based affiliations, I am a displaced person. Finding another visual representation of gravity and grace that does not cater to middle-and upper-class sensibilities becomes personally complicated. Is there one that is still obsessed with a body-based redemption but does not cotton to capitalist concerns; one that does not endlessly ascend but acknowledges and values the collapse as well?

I asked my mother to articulate what my grandfather wouldn’t and Kleist doesn’t—to tell a true story about how grace and redemption can be forged in this struggle against the gravity/force of other living bodies and the earth itself. I asked her to write what she could about my grandfather being a rider for the American and South American rodeo circuit. I thought that perhaps the tenuous orchestration of limb and lightness in the motions of the American bull rider would offer a modern working-class rehash of the Kleistian marionette. Weeks went by and she failed to write the logarithms of her dad’s work against gravity. He is dead and she was unsure as to how she would emotionally approach him in writing—the dad deferred, the handsome bull rider gone permanently horizontal.

Where do the similarities between the ballerina and bull rider begin and end? The classical ballerina and the American bull rider, in their shared struggle towards verticality, are similarly clad: the elevation of the cowboy boot and the en pointe ballet slipper, the unnecessary frill and thrill of the chaps and tutu, the glinting tiara, the sparkling winner’s belt. Both fetishize the instruments of their making: feverish loyalties to specific ballet slippers, engrained predilections for certain resins for waxing the rope that provides the rider’s handhold. The ballerina flits across the dimly lit proscenium; the cowboy flies through the fluorescent-lit dust of the roofed rodeo stadium. Both consistently break their bodies in their pursuit of defying gravity: the ballerina selects slow crippling in the form of permanent bone damage and the internal ravages of starvation diets, while the bull rider makes good on a fast death by way of concussions, busted ribs, broken noses, and alcohol as painkiller. It is only recently that a helmet in the shape of a cowboy hat has been worn by certain bull riders—a preventative measure that leaves physically intact spectators guffawing. One wonders if rapture and redemption are dependent on the risk of shattered craniums.

My mother finally writes what she can recall of a beautiful body in dangerous motion:

My Dad grew up with horses and worked on ranches from an early age. I remember he would travel around following the rodeo circuit ... Indian reservation circuit ... South American circuit ... San Joaquin Valley. … He was six feet tall and slender—strong—muscular in a lean way—always in cowboy boots or his socks—same high cheekbones as you and me. He often had cracked ribs and bruises from bull riding and the occasional broken nose or limb. However he often had similar injuries from getting in bar fights. The last time I saw him his ribs were wrapped.The bull rider’s center of gravity is located in the stomach, and his arms, legs, neck, and head are flung into position after position in what could be deemed a gut-based choreography. The rodeo crowd desires the flat-out loveliness of the cowboy’s limbs aligning with the center of his gravity and the motion of the beast beneath him. If he is a good rider, he will relax within the constraints of the ride—one hand gripping, one hand free, body tilted slightly forward, boots lightly spurring flank, and eight seconds to hold against all motion moving against him. And like Kleist’s description of the marionette, “When the centre of gravity is moved in a straight line, the limbs describe curves. Often shaken in a purely haphazard way, the puppet falls into a kind of rhythmic movement which resembles dance.” In this measured flail of the rider—measured because he will be disqualified if any part of his body touches any other part of his body or the bull—one can sometimes see the port de bras of the ballerina, the fineness of the wrist’s angle, the specific positioning of the feet.

Yet unlike the ballet enthusiast, the rodeo spectator desires the fall as much as the flight; the bull rider’s performance can serve as a rough-and-ready remedy for one’s own wounds. In a process akin to homeopathy, failure heals failure. The collapsing cowboy takes the literal fall echoed in his working class constituents’ daily protocol. And the down and out are soothed by the sheer fact of a breakdown outside of themselves, that they are not the only ones who break under duress while in the throes of gravity. Like in many a country western caterwaul, the spectators indulge in the sorrows of others in order to defer the trauma of their own grief. Metaphors pile up in the form of bodies that cannot hold on—to sweethearts, to jobs, or to the saddle horn.

Ultimately both bodies, ballerina and bull rider, exhibit an intimate struggle with gravity within the collapsed spatial context of this article; their dual performances offer comparative crystallizations of gender. But in the end, where the ballerina appears to be capable of only ascent and the bull rider skillfully encapsulates flight and fall, I begin to wonder if it is the taxonomy of flying or the taxonomy of falling that we are really after when we begin to break down the pleasures of a body temporarily released from rigors of gravity. Like Kleist’s protagonist in the conclusive paragraph of On the Marionette Theatre, “we see that in the organic world, as thought grows dimmer and weaker, grace emerges more brilliantly and decisively.” There is a hunch and a hope that failing at theorizing the flight and the fall could lead one back into the proverbial grace of the body.

- All quotes from Heinrich Kleist’s “On the Marionette Theatre” (1810) are from Idris Parry’s 1978 translation for the London Times Literary Supplement. Available at southerncrossreview.org.

Mary Walling Blackburn was born in Orange, California, in 1972. She is an artist and writer. She lives in New York City.