A National Automobile for a National Economy

Monocultures, motorcars, and New Zealand’s Trekka experiment

Michael Stevenson

[New Zealand] has such special economic characteristics as to group it with Sierra Leone, Ghana, Malaysia, Cuba, Bolivia, Chile, Honduras, El Salvador, Venezuela, and some others. The common characteristic of these countries is a dependence on the cultivation, exploitation, and export of one or, at most, two products. Such economies have been called monocultures.

As the years have gone by, New Zealand has increasingly specialized—to such an extent that today 95% of the value of its exports comes from grass which is processed by two animals, the cow and the sheep, to produce four main products, wool, meat, butter, and cheese, and several minor products such as casein, dried milk, hides, skins, tallow, sausage casings, and grass seeds.

—Dr. W. B. Sutch, “Programme for Growth: Industrial Development Conference” (Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Industries and Commerce, 1960)

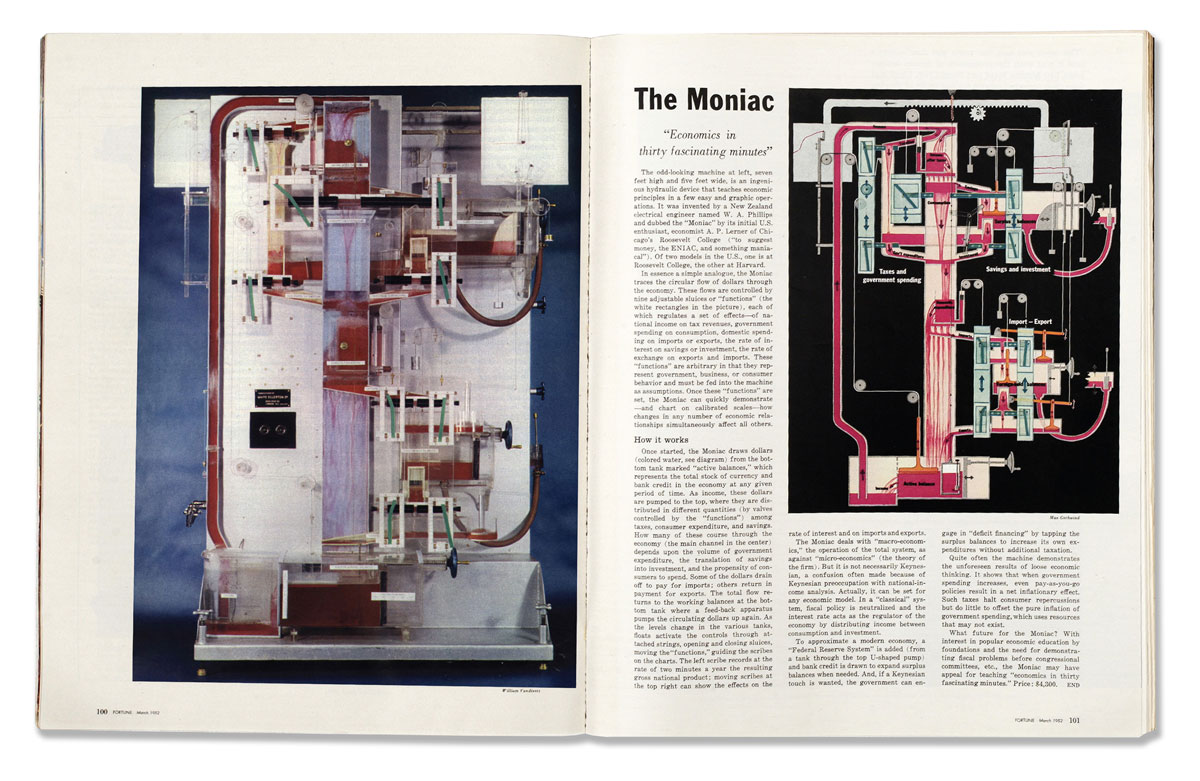

The brilliant yet cumbersome Phillips Machine (known in the United States as the “Moniac”) was invented in 1949 by the New Zealand economist Bill Phillips. This antediluvian calculating machine, in effect a water-powered computer, provided sophisticated analysis of national income and could model an entire national economy. The circulation of fluids through a series of sluices, chambers, and pipes represents the flow of money around the economy. Due to mechanical limitations and Keynesian preoccupations, it modeled the nation as a closed system, paying little regard to larger global realities. In this way it can be seen as the physical representation of the political economy described by Dr. Sutch.

The chronic shortage of overseas funds characteristic of a monoculture made the importation of motorcars one of the most contested sectors in 1960s New Zealand. After World War II, the increased standard of living created a high demand for new cars, a demand that exceeded supply. The motorcar industry, like all other private enterprise at the time, was government-regulated right down to the last bolt. Rationing imports was seen as the way for a small economy, dependent on a narrow range of agricultural products for foreign currency, to maintain its position in the Western world. The unrestricted importation of motorcars represented a large strain on these funds.

The Trekka, a simple agricultural utility vehicle, stands out as New Zealand’s only attempt to design and mass-produce a national car. The vehicle’s importance as a visual symbol of Cold War strategizing makes it a particularly interesting case study. New Zealand anticipated a leading role for itself in the event of a nuclear endgame: it would be the island of survival, the only First World country to remain completely untouched. Government planning overlapped with such thinking by favoring import substitution, a model for self-sufficient production that stressed local surrogates as replacements for imported goods. The Trekka was produced in an era when central planning governed much of the productive sector in New Zealand. Its new-car market was the most regulated in the Western world: strict import controls kept new vehicles in short supply; duty and taxes ensured the price to the consumer remained high. As a result, motorcar production, which had defined industrial ascendance in Detroit, was pursued piecemeal in New Zealand some 60 years later as a step towards independence and economic maturity.

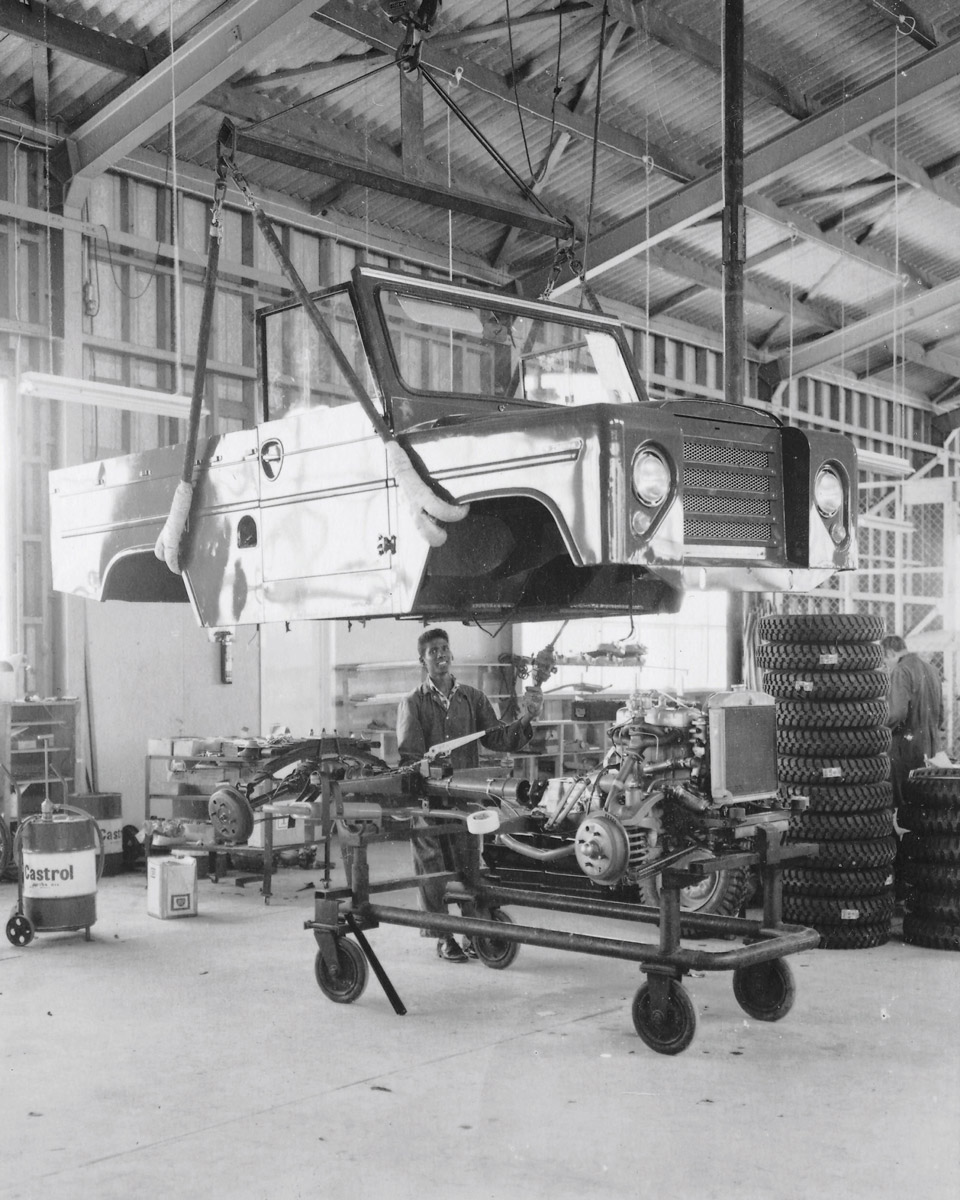

The first Trekka rolled off the production line in 1966 and, in its five years of production, a total of 2400 were manufactured. The Trekka was an unlikely symbol for a nation with industrial aspirations. The result of an ambitious car-assembly industry, it was not entirely made in New Zealand but fabricated around existing Czechoslovakian mechanical components in a partnership deal with the CSSR state trade agency Motokov. Skoda motors and chassis were packed as kits and exported to New Zealand where Trekka bodies were simply bolted on. The totalizing methods of Fordism contrasted with New Zealand’s backyard construction; a mesh of deals was minutely cobbled around import restrictions, state-directed global commodity trading, and case-by-case, state-sanctioned industrial expansion. In this climate, a national car could be produced without ever manufacturing mechanical parts.

This venture was made possible by the entrepreneurial expertise and international travel of an ingenious antipodean businessman, Noel Turner, otherwise known as the “Communist Millionaire.” Operating in the private sector as the president of his own company, Motor Holdings, Turner brilliantly negotiated the government-regulated game of import substitution to his own advantage. He was a socialist, but contemporaries saw this stance, at least in part, as a convenient way to realize his brand of economic nationalism. He was, above all, a wheeler-dealer, and bartering across Iron Curtain barriers became a natural extension of this philosophy. Anticipating later New Zealand Dairy Board transactions in Eastern Europe, he offered sheepskins for Skoda parts. He also once famously clinched a Trekka deal with sausage casings, a by-product of the grass economy and particularly scarce in the East Bloc. Brokering such “double-agent” deals was mostly overlooked in car-starved New Zealand; in short, the appetite for new vehicles meant the nation cared little about the origin of mechanical parts.

Yet Trekka production attracted international interest in unusual ways. The New Zealand/Czechoslovakia partnership drew the interest of intelligence officers from both sides. Czechoslovakian “party minders” arrived in New Zealand for the purposes of “engineering updates.” New Zealand Security Intelligence Service agents also kept files on the movements and associates of the entire Trekka management. A small number of vehicles were sent as medical transport to war-torn South Vietnam to fight the spread of communism. The Trekka also gained attention in developing nations such as Indonesia. Several hundred vehicles in kit form were shipped from New Zealand to Jakarta where they were assembled under license from Trekka and Skoda.

Nations such as Pakistan, Zambia, and the Philippines were also interested in producing the vehicle where rudimentary motorcar production seemed particularly well suited to local manufacturing conditions. The story of the Trekka thus positioned New Zealand within an unusual constellation of alliances and trading partners. It was an enterprise only possible from the extreme end of global supply lines, be they Soviet or capitalist. Aspirations to produce a motorcar at this time were as visionary as they were backward in that they prefigured a new place for the nation within a pragmatic kind of globalism.

As part of my contribution to the 2003 Venice Biennale, the Trekka took on a new role as national representative for New Zealand in a large installation that resembled a trade fair from the 1960s. New Zealand participated this year only for the second time, having first arrived in Venice in 2001 some 100 years after the inception of the Biennale. Locked out of the Giardini, it has long tried to come to terms with its Second World status. Constrained and out of step with global cultural economies, New Zealand is nevertheless keen to engage with and be recognized by First World countries. And so the project—the production of a national car in New Zealand in the 1960s—becomes an elegiac metaphor for a country’s search for artistic autonomy.

Michael Stevenson, a Berlin-based artist, represented New Zealand at the 2003 Venice Biennale. He shows his work in New York at Lombard-Freid Fine Arts.