The Art of Laughter

Three ways to be funny

Jim Holt

It involves the contraction of some fifteen facial muscles, along with the simultaneous stimulation of the muscles of inspiration and those of expiration, resulting in a series of respiratory spasms accompanied by a burst of vowel-based notes. Healthful side-effects of this experience are believed to include oxygenation of the blood, reduction in stress hormones, and a bolstering of the immune system through heightened T-cell activity. If the experience is sufficiently intense, however, cataplexy can set in, leading to muscular collapse and possible injury. In rare cases the consequences are graver still. Anthony Trollope had a stroke while undergoing this experience in response to the now-forgotten nineteenth-century novel Vice Versa. And, according to tradition, the ancient Greek painter Zeuxis, reacting to the portrait of a hag he had just made, actually died of it.

What I have been describing, of course, is laughter. What is it about the humorous situation that evokes this response? Why should a certain kind of cerebral activity issue in such a peculiar behavioral reflex—a “luxury” reflex, moreover, that serves no obvious evolutionary purpose? As Voltaire mockingly observed in the entry under “Laughter” in his Dictionnaire philosophique (1764), “Those who know why this kind of joy that kindles laughter should draw the zygomatic muscle ... back toward the ears are knowing indeed.”

It is an oft-registered complaint that philosophers do not devote enough attention to laughter and humor. In the Oxford Companion to Philosophy (1995), for example, the entry under “Humour” opens, “Although laughter, like language, is often cited as one of the distinguishing features of human beings, philosophers have spent only a small proportion of their time and pages on it and on the allied topic of amusement when compared with the volumes devoted to the philosophy of language.” The entry under “Laughter” concludes by noting that “The topic deserves more attention in the philosophy of mind.” Scattered aperçus can be found throughout the Western philosophical canon; Plato deemed the proper object of laughter to be human vice and folly, and Aristotle declared the laughable to be a species of the ugly. Spinoza—a rather agelastic fellow himself, according to contemporaries—observed in his Ethics (1677) that “Laughter is merely pleasure” and, as such, is “in itself good.” Hobbes, Kant, and Schopenhauer all hazarded somewhat elliptical theories of humor as asides in major writings. Only Henri Bergson devoted an entire treatise to the subject; in Le rire (1899), he defined the comic as “the encrustation of the mechanical on the living”—the paradigm case, disappointingly, being a man slipping on a banana peel.

Yet no figure in the philosophical tradition has produced a sustained account of humor and laughter that bears comparison with Sigmund Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905). Freud’s interest in the problem of humor was not primarily philosophical. Rather, he was specifically attracted to jokes—a subgenre of the humorous—because of their many likenesses to dreams. (When Wilhelm Fleiss was reading the proofs of The Interpretation of Dreams in the fall of 1899, he complained to Freud that the dreams seem to contain an awful lot of jokes.) In both jokes and dreams, Freud observed, meanings are condensed and displaced; things are represented indirectly or by their opposites; fallacious reasoning trumps logic. Jokes, like dreams, arise involuntarily (and, also like dreams, tend to be swiftly forgotten). From these similarities, Freud inferred that jokes and dreams share a common origin in the unconscious and are both essentially means of outwitting the inner “censor.” Yet there is a critical difference, he added. Jokes are meant to be understood; indeed, this is crucial to their success. Dreams, by contrast, remain unintelligible even to the dreamer, and are therefore totally uninteresting to other people. In a sense, a dream is a failed joke.

There are three competing theories of jokes. The “superiority theory,” which can be traced back to Plato and Aristotle, holds that we find something risible when we feel superior to it. The classic statement of this theory was supplied in the seventeeth century by Hobbes, who declared that laughter expressed “a sudden glory arising from some conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others.” On this theory all humor is at root mockery and derision, all laughter a slightly spiritualized snarl.

A second traditional theory of humor, the “incongruity theory,” was hinted at by Aristotle (in the Rhetoric he observed that a good way to get a laugh was to set up your audience to expect one thing and then to hit them with a surprising punchline) and worked out in detail by Kant in his Critique of Judgment (1790), and by Schopenhauer in The World as Will and Representation (1819). The gist of the incongruity theory is that we laugh when two things normally kept in separate compartments in our mind are unexpectedly yanked together. On this rather intellectualist account, a joke forces us to perceive incongruities: between the decorous and the low, the ideal and the actual, the logical and the absurd.

Finally there is the “relief theory” of humor, which was pioneered by Herbert Spencer and given its most elaborate statement by Freud. Laughter, Freud submitted in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, is essentially a release of excess energy. Where does this energy come from? From the temporary lifting of an inhibition. Keeping down forbidden impulses, Freud held, requires an expenditure of psychic effort. When the cunning devices of a joke force such a thought or feeling to be entertained (by presenting it in an outwardly innocent guise), the energy used to maintain the inhibition against it suddenly becomes superfluous. It is therefore available to be discharged through the facial and respiratory muscles in the form of laughter.

Of these three theories of humor, it is the incongruity theory that is taken most seriously by philosophers today. It too, however, is open to objections. Why should incongruity be a source of pleasure? Shouldn’t the asymmetrical, the disorderly, and the absurd cause bewilderment and anxiety in rational creatures like ourselves, not merriment? The nineteenth-century philosopher Alexander Bain observed, “There are many incongruities that may produce anything but a laugh. A decrepit man under a heavy burden, five loaves and two fishes among a multitude, and all unfitness and gross disproportion; an instrument out of tune, a fly in ointment, snow in May, Archimedes studying geometry in a siege, and all discordant things; a wolf in sheep’s clothing, a breach of bargain, and falsehood in general; the multitude taking the law into their own hands, and everything of the nature of disorder; a corpse at a feast, parental cruelty, filial ingratitude, and whatever is unnatural; the entire catalogue of vanities given by Solomon—are all incongruous, but they cause feelings of pain, anger, sadness, loathing, rather than mirth.” (Bain was a Victorian with little capacity for the darker forms of humor, but there is something to his point.)

• • •

The idea that all jocularity was harmful to moral character was widespread at the beginning of the Victorian era. The reason for this disapproval is not hard to fathom: by long tradition, laughter had been associated with blasphemy, with scorn for the outcast and infirm, and, above all, with obscenity. As folklorists have documented, the vast majority of jokes in oral circulation have always been about sex. Such “dirty jokes” served to lure the innocent into sexual degradation, it was believed. Women, in particular, were supposed to be too good to laugh. Only slightly less corrupting was the sort of pitiless laughter directed at the misfortunes and vices of others, at the drunkard, the cripple, the cuckold, the foreigner. It was the duty of the decent, charitable man to refrain from jests directed at such butts. (This sentiment, by the way, was not confined to the priggish Victorians. Baudelaire, in his essay “De l’essence du rire”, denounced laughter as springing from “the idea of one’s superiority— a satanic idea, if ever there was one!”)

In the mid nineteenth century, however, a shift in attitude can be detected. The joke impulse—once seen as actuated by feelings of superiority, aggression, and lust—came to acquire something of an intellectual aura. Comic theorists like Coleridge, Leigh Hunt, and Sidney Smith, taking a leaf from Kant and Schopenhauer, began to put witty paradox at the heart of jocularity. It is significant that the meaning of “wit” has evolved from referring to intellect in general, to the ability to perceive connections between ideas, to a quickness at perceiving incongruous resemblances that evoke delighted surprise. A really good witticism reveals a discrepancy between the ideal and the real, it was argued; laughter had a kind of logical power to destroy solemn untruths, allowing truth, in all its robustness, to survive. It was a powerful weapon against bigotry and false enthusiasm. Joke-making ceased to be thought of as entirely disreputable, and susceptibility to jokes, at least those of the drier, more cerebral sort, became a social plus. Leslie Stephen, writing in the Cornhill Magazine in 1876, remarked that “a fashion has sprung up of late years regarding the sense of humour as one of the cardinal virtues.” A few decades later, Max Beerbohm observed that a man would sooner confess to lacking a sense of beauty than to lacking a sense of humor.

Perhaps the reason it is so hard to pin down the essence of jokes is that it doesn’t hold still. It is not an unchanging Platonic form, but something that evolves over time. Born of lewdness and aggression, the jocular impulse aspires to the delicate perception of pure incongruity. At what rarefied telos is this evolutionary process aiming? Why, the Jewish joke, of course—or, to be more precise, the Talmudic joke. The abiding themes of Jewish humor are not sex and superiority, but logic and language. Take this rather feeble specimen cited (and explicated at some length!) by Freud: Two Jews met in the neighborhood of the bath-house. “Have you taken a bath?” asked one of them. “What?” asked the other in return, “is there one missing?”

Jewish humor deploys crazy logic as a way of coping with the incomprehensible. This places the Jewish joke very close to another jocular genre of great rarefaction, the philosophical joke. The best philosophical jokes tend to be evoked by the most persistent incomprehensibilities. Take the question that Martin Heidegger deemed the deepest and darkest in all of philosophy: Why is there something rather than nothing? When I posed it to the Columbia philosopher Arthur Danto a few years ago, he replied rather sharply, “Who says there’s not nothing?” On another occasion I pressed Danto’s colleague, (the recently deceased) Sidney Morgenbesser with the same question. “Even if there was nothing,” Morgenbesser wearily said, “you still wouldn’t be satisfied!” Many years ago, the Oxford philosopher J.L. Austin was delivering a paper about language to a big audience at a conference. In the course of his address, Austin raised the matter of the double negative. “In some languages,” he observed, (here I paraphrase) “a double negative yields an affirmative; in others, it yields a more emphatic negative. But in no language, natural or artificial, does a double affirmative yield a negative.” At which point Morgenbesser piped up from the back of the room, “Yeah, yeah.”

One can imagine the wave of Homeric laughter that must have spread through the audience on this occasion. But what, exactly, did it express? Albert Rapp, in The Origins of Wit and Humor (1951), argued that all human laughter evolved from a pre-linguistic “roar of triumph in an ancient jungle duel,” a roar that would pass contagiously from the victorious combatant to his kin standing on the sideline. Are we to suppose, then, that the laughter evoked by Morgenbesser’s quip was a collective roar of superiority at the slaying of an opponent by a philosophical counterexample? Or are we to suppose, with Freud, that it was a mass discharge of psychic energy freed up by the temporary lifting of an inhibition against being frivolous at academic conferences? If we assume, as the incongruity theory would have it, that the philosophers were simply relishing an especially neat inversion of logic, then why all the noisy and convulsive chest-heaving? How did such a peculiar motor response get attached to the aesthetic enjoyment of the incongruous?

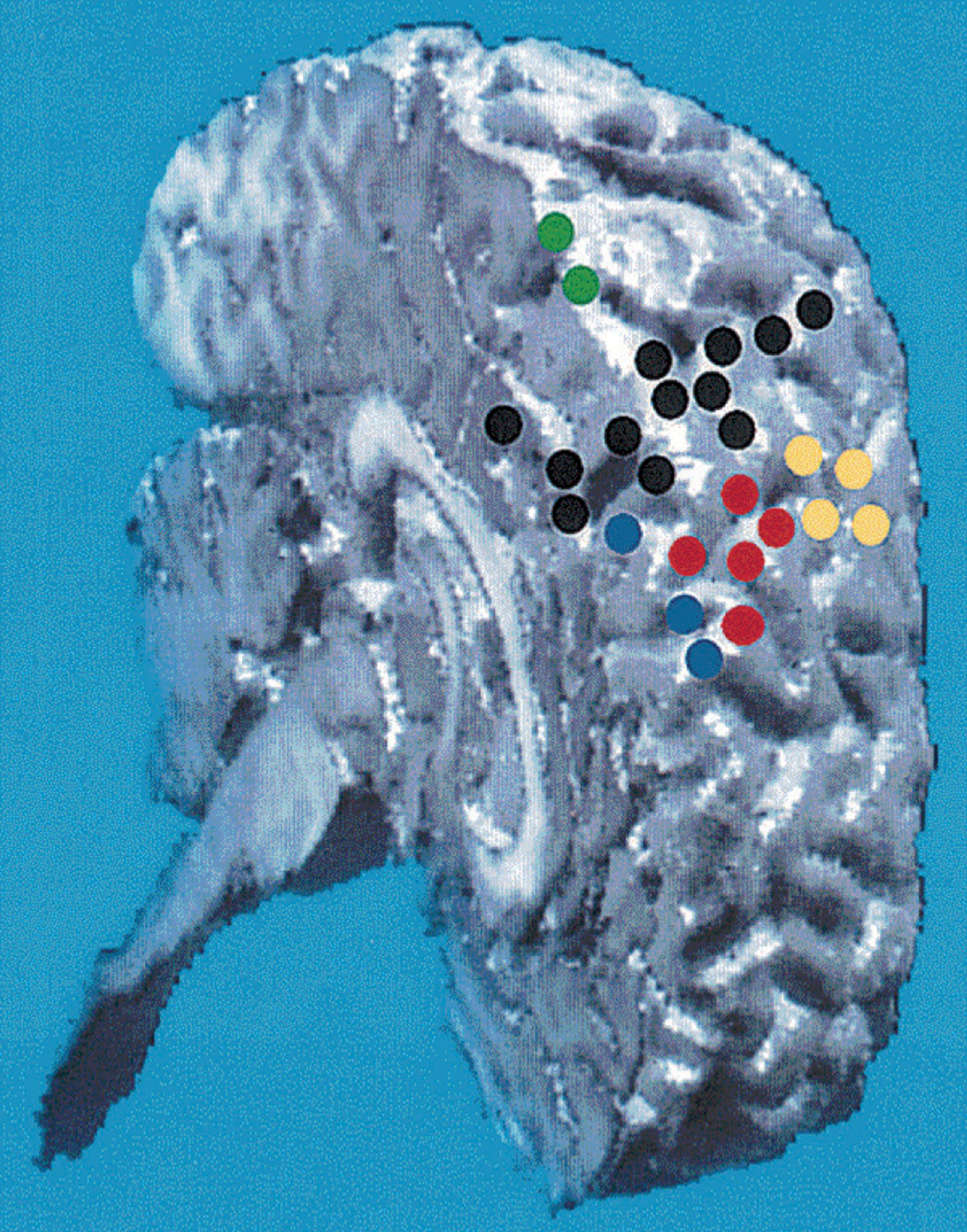

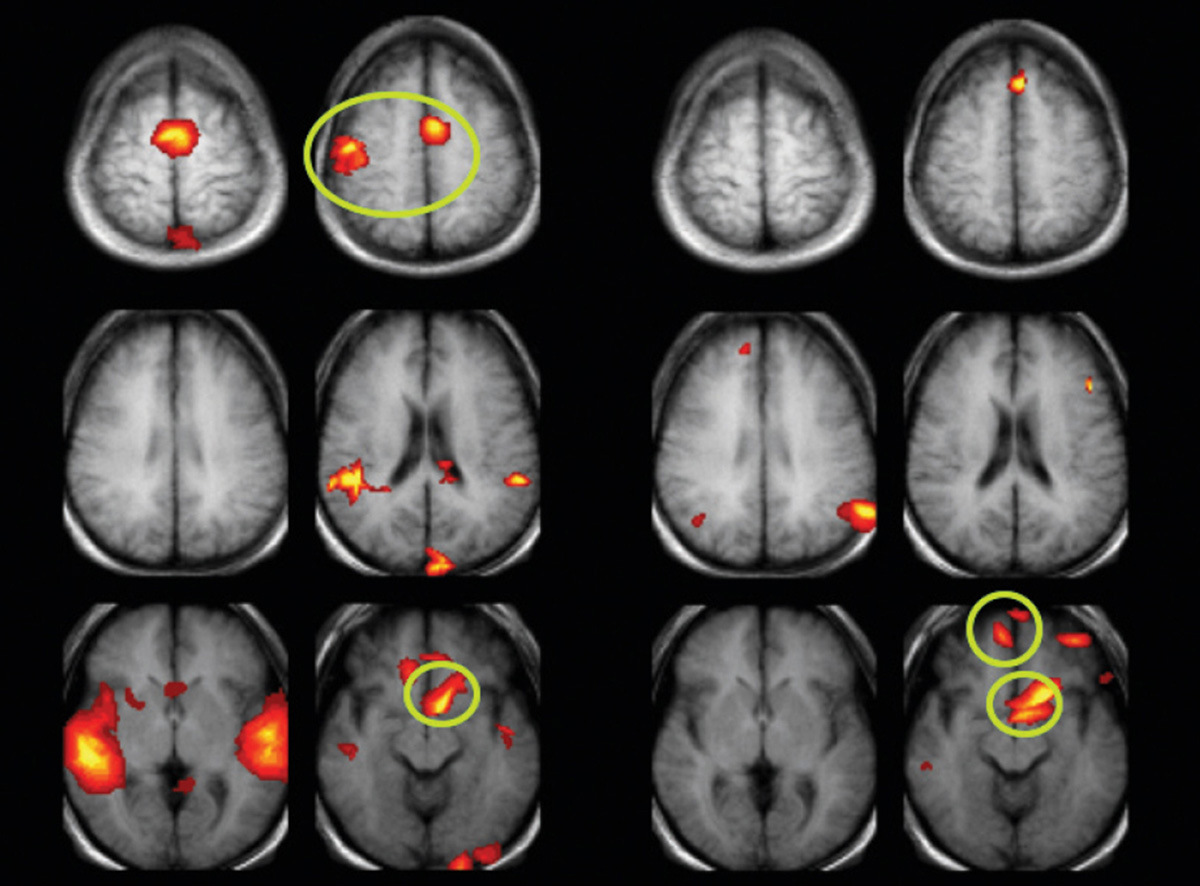

Though it takes place in the most recently evolved part of the human brain—the higher cortices—amusement at the contrived absurdities of jokes taps into more primitive circuitry that we share with our apish cousins and thereby produce laughter. Brain damage can rob you of your sense of humor, just as surely as it can impair your ability to grasp metaphors and make creative connections. It appears to be the right frontal lobe that is crucial for “getting” jokes. Patients with lesions in this area have a terrible time distinguishing humorous from neutral statements (humorous example: a sign in a Tokyo hotel—GUESTS ARE INVITED TO TAKE ADVANTAGE OF THE CHAMBERMAID), and are little inclined to laugh.

Jokes are products of human ingenuity that, at their driest and most refined, fall within the domain of art. Yet I know many people who abhor them—even people blessed with a rich sense of humor. Perhaps that has to do with the origins of most jokes. Freud claimed that the most compulsive jokesmiths are neurotics, because they are most plagued with strong impulses from their unconscious. Sociologically speaking, the most fecund sources for jokes would seem to be Wall Street traders and inmates of prisons. We have all been tortured by amateur comics who cannot repress the urge to tell jokes, and some have even been tortured by being made to tell jokes. Evelyn Waugh, convinced that his son James had no sense of humor, forced the poor child to tell him a new joke every day as a kind of remedial therapy. “In desperation,” Waugh’s biographer Selina Hastings tells us, “James bought a book of a thousand and one American jokes, and stammered through each day’s installment at lunchtime, while his father sat stony-faced, refusing to laugh.”

See press about “The Art of Laughter” in Abece Azorro.

Jim Holt is a gossip columnist for New York Magazine. He also writes about philosophy and science for the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and Slate.