Artist Project / The Match Game

Speak, memories

Sasha Chavchavadze

In Speak, Memory, Vladimir Nabokov describes a match game he played as a child with an old general. He recalls with filmic precision the general’s “thickset, uniform-encased body creaking slightly” as he placed the matches end-to-end saying, “This is a sea in calm weather.” He changed them to a zigzag saying, “A stormy sea,” and was abruptly called away with a “flustered grunt” to command the World War I Russian army in the Far East. Years later, after the war and a revolution, in a chance encounter on a bridge, Nabokov’s father met the general again, dressed as a peasant, asking for a cigarette light. “What pleases me is the evolution of the match theme,” Nabokov writes, “those magic ones he had shown me had been trifled with and mislaid, and his armies had also vanished, and everything had fallen through...”

From: S. Chavchavadze

Sent: Sunday, October 06, 2002 1:00 PM

To: D. Chavchavadze

Subject: match game

Can you describe the match game you played when you were a boy? I started to think about it when I read about a match game in Nabokov’s “Speak, Memory,” so I wondered about your matches.

From: D. Chavchavadze

Sent: Sunday, October 06, 2002 4:48 PM

To: S. Chavchavadze

Subject: match game

The match game was invented by me in 1940. In those days there were kitchen matches that could be lit by almost anything, and different companies had different colored match heads. The matches represented individual soldiers, and had insignia of rank. The matches could be put in trenches or foxholes. If it was my turn I fired a BB gun at the enemy’s matches, one shot for each match I had on the front. There was also artillery represented by rocks being lobbed at the enemy. Matches that were knocked down were “wounded” and given a stripe. If a match was lit, it was dead. I have never described this in writing. Would be glad to answer more questions.

My father, David, has decided to travel to Russia for the first time, and has invited me to join him since I have learned to speak Russian. It is 1974 and he goes to the Soviet Embassy in Washington to introduce himself and ask for a visa. He meets with an embassy official and says, “My name is David Chavchavadze. I worked for the CIA for thirty years and I would like to take my daughter to Russia.” The official looks stricken, apparently briefly thinking that David is defecting, and disappears for a few minutes. When he returns he says “Vsyo budyet normal” (“Everything will be normal”).

David once told me that the only accurate depiction of a spy in the movies was the one by Richard Burton in A Spy Who Came in from the Cold, based on the le Carré novel. Unlike James Bond, a real spy has to be completely innocuous, to the point that when he walks into a restaurant nobody notices. Though David is a handsome man, he carries himself in an understated way, wearing a short raincoat and walking with a shuffle. Once I was riding the subway to Brooklyn, drinking a cup of coffee, when I looked up and saw David sitting across the subway car, carrying a small plastic bag, looking at me as if deciding whether to speak. Though retired from the CIA, he was doing contract work, interviewing Soviet émigrés living in Brighton Beach. The plastic bag was part of his cover, making him look like any other guy on the subway.

From: S. Chavchavadze

Sent: Monday, October 07, 2002 5:43

To: D. Chavchavadze

Subject: match game

How did you mark the insignia on the matches — with different colored paint? Or did you cut notches in them? Did you start with fresh matches each time, i.e. new battles, or was it the same war played endlessly with the same old soldiers? What colors were the match heads? These days parents would freak out. Kids don’t have BB guns or play with matches.

When we flew to Moscow together, David’s carry-on luggage was also plastic, a cheap variety of over-the-shoulder tourist bag, white with a logo. Our trip to Russia went smoothly. There was no sense of being followed or watched, though David was convinced that the flowers given to me by a young man in the Leningrad Hotel contained a microphone. He was clearly nervous about going to Russia for the first time; not only had he spent his career as an operative specializing in Soviet affairs, but his grandfather was a Romanov Grand Duke, executed by the Bolsheviks in 1919. David’s parents fled Russia, never to return.

David was born in London in 1923, and raised as a Russian in exile. His mother had played with the Tsar’s children, and was the same age as her cousin, Anastasia, whom she disliked. In her memoirs, she describes a fight she had with Anastasia: “...fists flew, hair was pulled and we scratched and we bit each other. All this went on in complete silence except for sounds of heavy breathing and crashing furniture. ... We emerged disheveled, bleeding and covered with bruises. Oddly enough nothing was ever said to us by the grown-ups and nobody was scolded or punished.”

David’s grandfather was executed with his brother, Nicholas, a historian known for his socialist sympathies, whose book on Asian lepidoptera is cited by Vladimir Nabokov as inspiring his passion for butterflies. The brothers knew that revolution was inevitable, and had urged the Tsar to grant a full constitution. Hours before they were executed, the writer, Maxim Gorky, asked Lenin for a stay of execution based on Nicholas’s socialist sympathies, which was granted. Gorky rushed to the Peter and Paul fortress, but arrived too late.

From: D. Chavchavadze

Sent: Tuesday, October 08, 2002 4:44 PM

To: S. Chavchavadze

Subject: match game

My army was Ohio blue tips, blue and light blue. Others were black and white, light blue and red, red and white. Everybody was free to make up their own insignia. Mine was red or black pencil, round lines for officers, chevrons for non-coms. The lower part of the match was for black wound stripes. Fresh matches were introduced to replace those killed, and the wounded were returned to duty in every new game. We did not bother to define wars. This is fun for me, but why all the interest in the match game?

Like many brilliant young men, David was recruited out of Yale into the CIA in 1950. Though his parents mourned the loss of their family members, they were surprisingly uncritical of socialism. They hated the Soviet regime but were sympathetic to the causes that drove the Revolution. They were pacifists, whose friends, American intellectuals like John dos Passos and Edmund Wilson, espoused socialism in the 1920s. Like many second-generation immigrants, David chose a different path from his parents. Always interested in the military as a child, he joined the Knickerbocker Grays, a military program for society boys, where he rose to the rank of colonel, and invented elaborate military games played with matchsticks.

In his memoir, Crowns and Trenchcoats, David recalls his initial difficulty adapting to life in the CIA. “After a couple of weeks my mind became compartmented... There was always the terrible temptation to tell people interesting tidbits, or to hint that I knew something they did not. This would have been a violation of the Great Taboo, an unpardonable sin.” Secrecy, he wrote, eventually became second nature to him, and he soon felt absolutely no temptation to reveal anything.

In the CIA, he was stationed in Berlin before the Wall. He describes the city with its four national demarcation zones. The Soviet Sector was off-limits to the Americans, one of the first manifestations of the Cold War. He spent hours walking the streets, the most effective way of identifying enemy surveillance teams; if you walked long enough, it became clear who was following you. He and his colleagues would stroll in parks with their wives and children, a perfect cover while making contact with agents.

From: S. Chavchavadze

Sent: Wednesday, October 09, 2002 4:24 PM

To: D. Chavchavadze

Subject: match game

Wonderful descriptions about the matches. A friend who grew up in Ohio said you could light Ohio blue tips on your pants zipper or teeth! Do the original matches still exist? I remember you told me you played the game into your fifties with your friends from the agency. I have been trying to recreate the match game. Wooden matches are hard to find. Cigar shops have a brand called “Swan” made in Sweden — short with salmon pink tips — and there are the long red-tipped supermarket variety. I’m always a bit nervous when I buy them in bulk, especially these days of heightened security.

David sits in a darkened room, the lit screen of a reading device in front of him, spending his final years poring over manuscripts, memoirs, and genealogies. He is almost blind, and without this special device, he cannot read at all. On one of my infrequent visits to Washington, he tells me he can hardly see me, that I am a blur. We are sitting, wedged awkwardly across from each other on two pillow-stuffed sofas in the house belonging to his third wife, Genia. I have many questions to ask him but feel somewhat constrained, sensing the same from him. It is as if the physicality of being in the same room with him after all these years is too much for both of us.

As a child I would visit David on weekends, though he was often overseas, sitting in hotel rooms around the world under aliases, directing the movements of his agents. He would show up periodically for short visits on his way back from clandestine trips. On one visit, he signed my scrapbook,“ D. was here, alias the Crooked Sixpence or the Wooden Øre.” In 1970, a Soviet defector stated that there was a mole in the CIA with a Russian name. Director James Jesus Angleton, whose close friend, Kim Philby, had recently been denounced as a spy, went on a witch hunt, implicating a number of people in the agency, including David, who took early retirement soon after.

Before I leave Washington, we exchange email addresses, something we have both just learned to do. When I get back to New York, I email him a question and, to my surprise, receive an immediate answer with great detail and a flourish of humorous anecdotes. We begin an almost daily communication; nothing heavy, mostly memories and stories, although once I ask him, “Have you really cared about me all these years?” to which he emails back an immediate assent. It was as if the sheer physicality of the older modes of communication, the voice of the telephone, and the hand of the letter, never worked. The great void of the Internet matched the silence that had grown up between us. Its lack of physicality, its detachment, almost clandestine in nature, enabled us to break the silence of forty-nine years.

From: D. Chavchavadze

Sent: October 24, 2004 5:04 PM

To: S. Chavchavadze

Subject: army found!

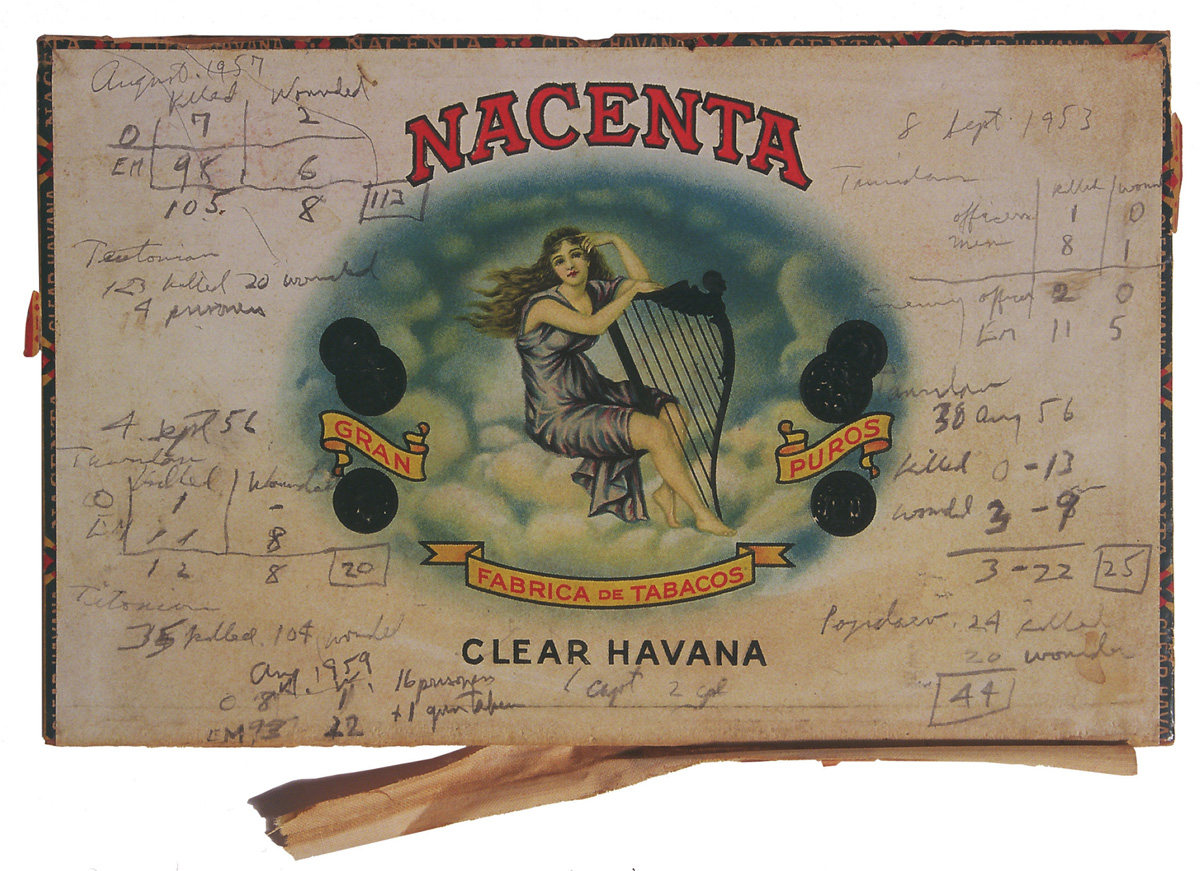

in a cigar box, I am happy to report — the entire original Tauridan Army (blue and light blue matches) and Cenraurian Army (red and white) are in the box, along with accounts of battles, a match-sized battle flag penetrated by several BB holes, and lots of ammunition. I will present them for your inspection whenever you appear.

Sasha Chavchavdze is an artist working on “The Museum of Matches,” an interdisciplinary project including installations and a book. She had a recent solo exhibit at the Kentler International Drawing Space in Brooklyn.