Hydropolis

Testing the waters

Brian Dillon

Have I drunk enough water today? That tumblerful I downed on the way to my desk: was it sufficient to counter what I’m assured are the physiologically shrinking and drying effects of the black coffee at 8 a.m., not to mention last night’s glass and a half of red wine? How ought I factor into the day’s hydration the effects of a forty-minute run first thing in the morning? This incipient throb in my right temple: does it presage a full-blown headache? Are the vessels of the brain starting to contract already, damming up the flow of words and ideas? And what of the skin? Is it supple enough, adequately aquified from day to day, to stave off for a time the signs of middle age? Best not to think, perhaps, of the liver, the kidneys, the soft tissues that for all I know are slowly desiccating as I write, crying out for the moisture that in my ignorance I have neglected to channel their way. Am I, in short, in danger of succumbing to that peculiarly contemporary malaise: dehydration?

Among the many small anxieties that crowd at the edges of one’s physical being in the early years of our century, few are so easily assuaged, so advertisers inform us, as this fear of drying out. A daily liter and a half of the pure element is what it takes, we’re told, to ensure that we don’t shrivel. We should count ourselves historically fortunate that our pseudoscientific imaginary does not demand a more thorough inundation, for this particular millennial craze is in part a curious return to the rigors of the Victorian water cure. In the middle of the nineteenth century, countless unhappy souls submitted themselves to the most alarming irrigations; a virtual archipelago of hydropathic, or hydrotherapeutic, institutions emerged in Europe, and latterly in the US, to restore dried-up, clogged, or plethoric bodies to their properly humid state.[1] They were distinguished from the outset from the already established spa towns and seaside resorts that had flourished in the eighteenth century: hydrotherapy relied on the curative effects of cold water itself, and not on any invigorating minerals that it might contain.

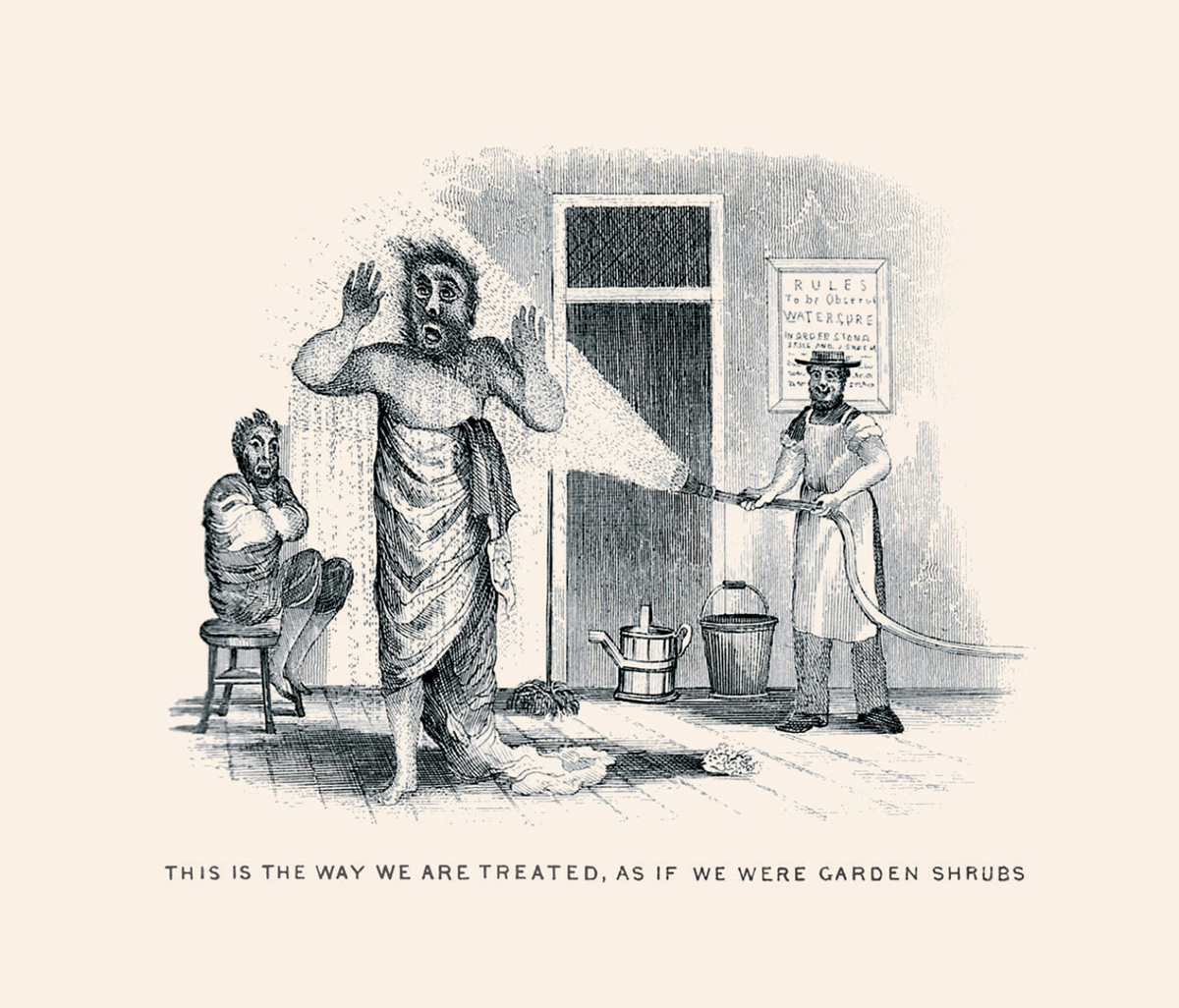

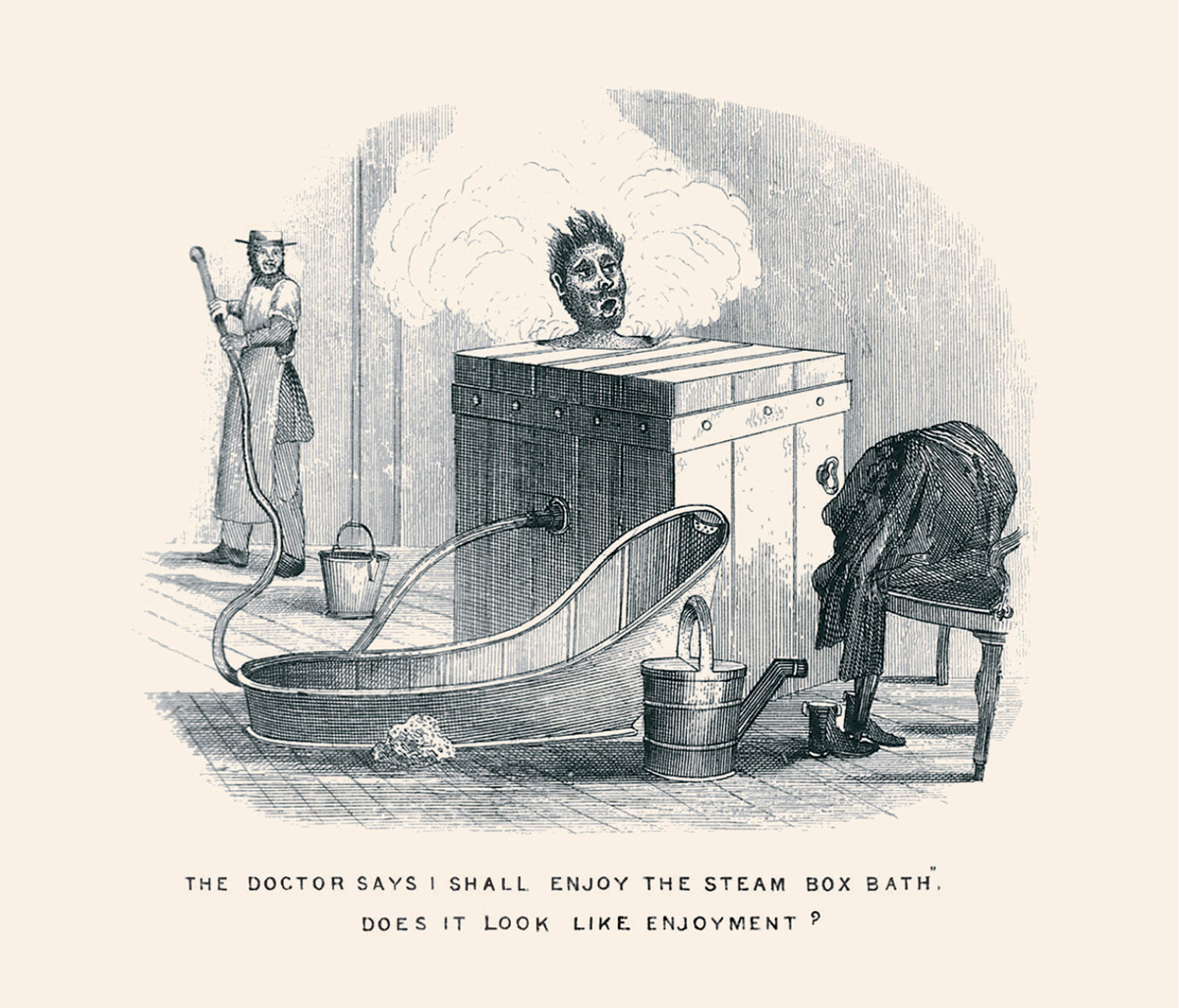

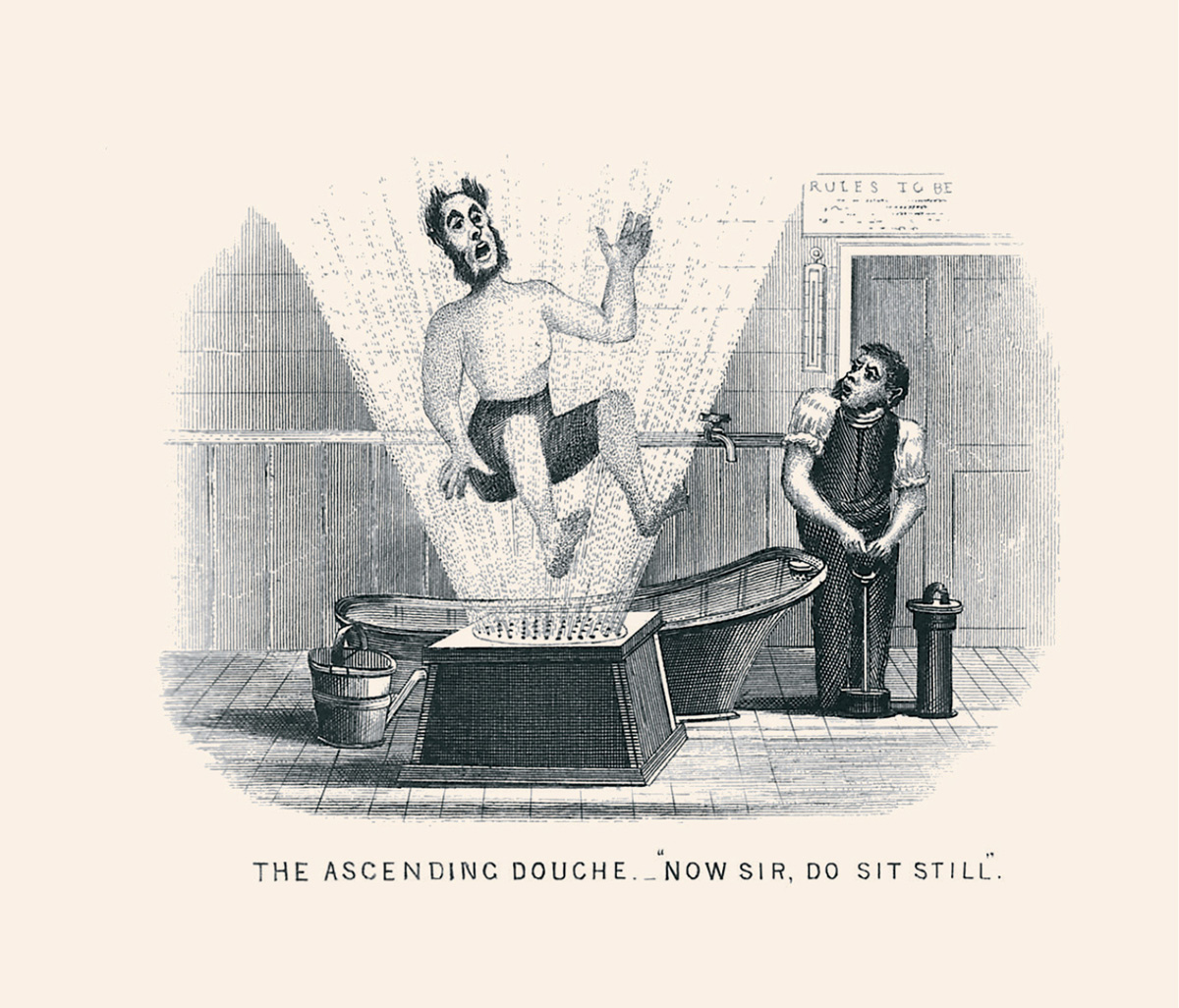

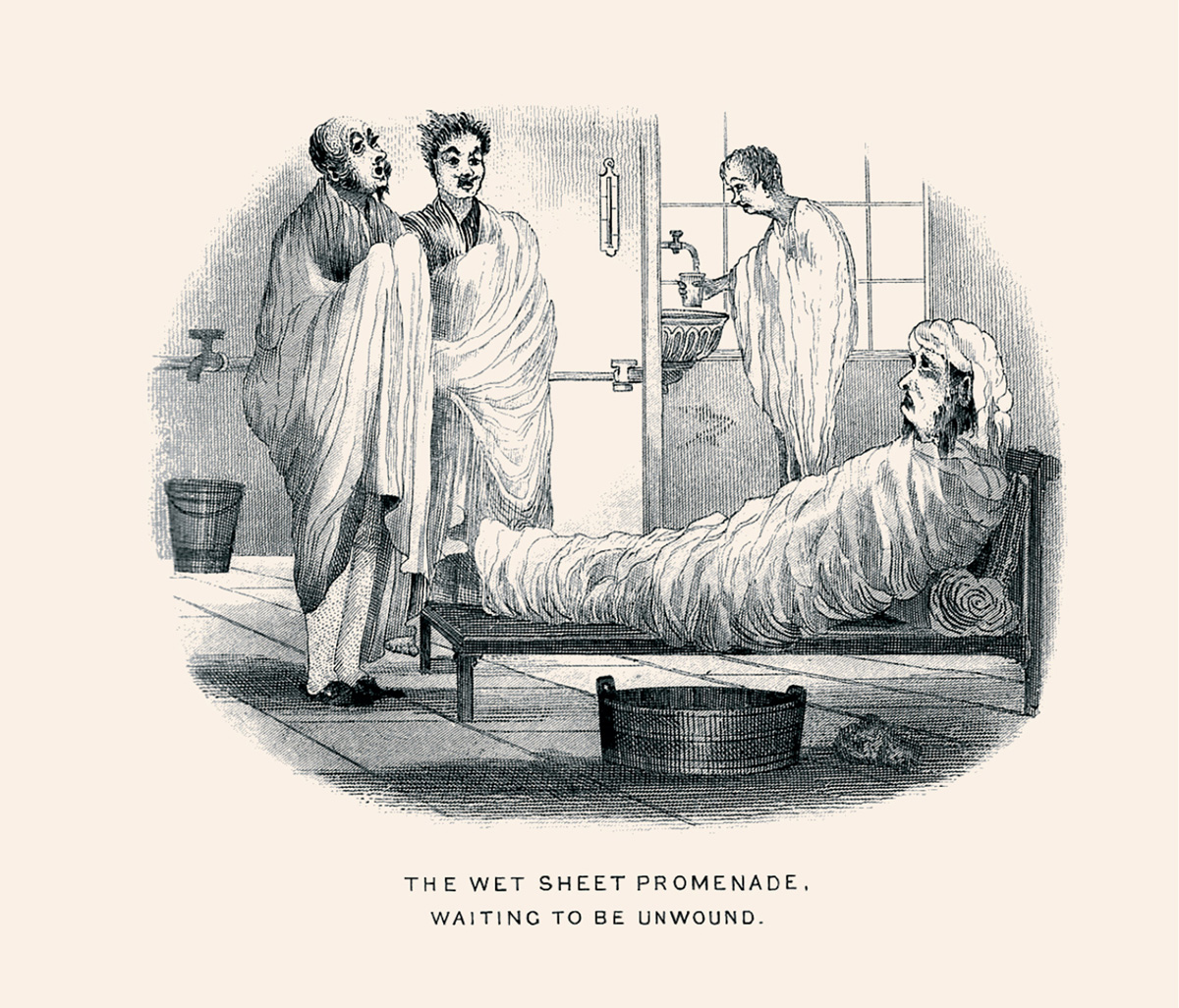

By mid-century, the methods and machinery differed little from one establishment to another; the unwell were sluiced, inside and out, according to accepted techniques. In the early days of hydrotherapy, the patient might merely be rubbed down with a cold, wet sponge, but this soon gave way to more exacting treatments. The wet sheet was the most basic: the individual was wrapped in sopping linen, in turn swaddled in a thick quilt, then overlaid by a feather bed, until only his or her anxious face was visible. As the treatment could last for several hours, a drinking tap was often placed at the upper extremity, and a urinal of some sort inserted at the lower. Released at length from this damp chrysalis, patients submitted, depending on symptoms and strength of constitution, to one of several sorts of bath: they dipped themselves in the plunge bath, sat up to their waists in the sitz bath, or inserted only their limbs in the arm and leg bath. Sturdier patients stood under the douche: a column of water descended from a variable height (sometimes up to twenty feet) and the subject gripped a horizontal pole lest he or she should be knocked to the ground as the cataract pounded on the head and shoulders. In a potentially traumatic variation on the simple descending douche, an ascending version was trained from below on the genital area. Throughout the course of treatment—which might last weeks or months, and invariably required certain dietary restrictions—copious amounts of cold water were ingested daily.

The list of ailments that hydrotherapists claimed to treat was impressively various, though it exempted some common killers of the era, such as consumption. Nor could it remove the non-lethal agony of gout. (Both the gouty and the consumptive, however, were said to derive some comfort and alleviation of their symptoms from cold water, even if it stopped short of a cure.) The conditions that responded to a protracted and comprehensive soaking included asthma, pleurisy, measles, scarlatina, smallpox, rheumatic fevers, scrofula, hernia, ringworm, tic douloureux, tumors of the heart, liver, and various glands, syphilis, and mercury poisoning. These last two commonly went together, and it has been estimated that up to half the clients of the first hydropathic establishments may have been syphilitics whose prior treatment with mercury had proven almost as debilitating as the disease itself. In all cases, what the hydropathist hoped for was a visible crisis of the patient’s system in the form of boils, itching, eczema, and efflorescence of the skin: all of these were said to result from prolonged use of cold water, and signaled the body’s efforts to rid itself of the corruptions within. If the skin failed to erupt, the purification might be effected instead via the bowels: the shivering, underfed patient was meant to rejoice at the onset of diarrhea.

• • •

Hydrotherapy had its origins in the small mountain town of Gräfenberg, two thousand feet up in Austrian Silesia. Various explanations circulated as to how Vincent Priessnitz, a farmer’s son born in 1799, had come to discover the water cure. It was said that as a young boy he had happened upon a roe, recently shot by a hunter, dipping its wounds in a spring until it had recovered. At the age of thirteen, claimed an alternative founding myth, he had hurt his wrist and thumb while trying to catch a bird, and applied a wet bandage which caused a skin rash as the injury healed. At eighteen, according to another narrative, he was run over by a wagon; several physicians despaired of his recovery, but Priessnitz rose from his bed, pushed his broken ribs back into place against a windowsill, and had himself wrapped in cold wet bandages. After a year, he had almost completely recovered.

Whatever his humble backstory, by the 1820s Priessnitz’s fame as a healer was such that, at the instigation of local doctors, the regional authorities tried him for unlawful medical practice. His sponges were subject to careful scrutiny, but no drugs were found and he was acquitted. Several such cases followed, but the “Water Demon of Gräfenberg” only drew more attention and acclaim, and in 1839 a commission sent from the Imperial Home Office in Vienna approved Priessnitz’s controversial practice. Despite the austere accommodation available to visitors, sometimes shared with local livestock, the “hydropathic university” began to attract a respectable clientele: royalty, aristocracy, military officers, civil servants, clergymen, and even physicians and apothecaries. On arriving at Gräfenberg, after pausing to admire a fountain dedicated to “The Genius of Cold Water” (erected by some satisfied patients from Moldavia and Wallachia), they were observed during their first ablutions by Priessnitz himself. Having read from the patient’s skin the state of his or her constitution, he recommended to his bathmen a particular course of treatment: some combination, perhaps, of the head bath, the sweating blanket, and the rubbing wet sheet. This last, recalled one visitor, was “dexterously thrown over the head so as to create surprise and a slight shock.”[2] The patients’ days were strictly regulated: they rose at 4 a.m., were divested of any extraneous flannel garments or mufflers that might cocoon them against the bracing cold, and took strenuous exercise in the mountain air.

By 1842, there were at least fifty hydropathic institutions in Germany, and many more elsewhere.[3] They tended to refer back to the original for their authority—Bridge of Allan was the Scottish Gräfenberg, Blarney the Irish Gräfenberg—and to rely on the fame of the founder. Priessnitz, however, was the Socrates of hydrotherapeutic theory: he wrote nothing himself—nor did he read, lest he damage his brain—and left the elaboration of his ideas to colleagues and successors. Two such acolytes were the founders of the English Gräfenberg, Dr. James Wilson and Dr. James Manby Gully. Wilson claimed to have been the first English physician to visit Priessnitz’s establishment, where he took 500 cold baths, 2400 sitz baths, spent 480 hours in wet sheets, and drank 3500 glasses of cold water. In 1842, he and Gully—a graduate of the University of Edinburgh and the École de Médecine in Paris, and lately, like Wilson, a physician in London—each set up their own establishment at Malvern, a spa town in Worcestershire noted for the purity of its springs. A decade later, it was rumored that each doctor earned £10,000 a year; among their patients were some of the most anxious Victorian dyspeptics and hypochondriacs: Charles Dickens, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Thomas Carlyle. “Here we are,” wrote Carlyle to Ralph Waldo Emerson in the summer of 1851, “assiduously walking on the sunny mountains, drinking of the clear wells, not to speak of wet wrappages, solitary sad steepages and other singular procedures.”[4]

The most famous resident at Tudor House, home to Gully’s Hydropathic Establishment, was Charles Darwin. In March 1849, having appraised himself of the fees, Darwin took his wife Emma and their six children, as well as a governess and servants, to Malvern. Installed in a rented house, he gave himself up daily to the aquatic ministrations of Gully’s staff. He rose, he wrote to his sister Susan, at a quarter to seven, and was immediately scrubbed with a wet towel for two or three minutes: his personal “washerman” scrubbed from behind, Darwin himself in front. He then drank a tumbler of water, dressed himself, and walked for twenty minutes: “I like all this very much.” He alludes to a wet compress worn throughout the day—it was refreshed by dipping in cold water every two hours—but does not say where exactly about his person it was placed. Darwin felt the beneficial effect of Gully’s personality before that of his treatment: “I like Dr. Gully much—he is certainly an able man. … He is very kind and attentive.” Before long he also reported himself feeling stronger, and his stomach, the seat of the illness that had sent him to Malvern, somewhat improved: “I expect fully that the system will greatly benefit me, and certainly the regular Doctors could do nothing. … Physiologically it is most curious how the violent excitement of the skin produced by simple water has acted on all my internal organs.”[5]

• • •

In 1846, Gully had published a book entitled The Water-Cure in Chronic Disease, and it is in these pages that we can properly discern the nature of the medical and cultural fantasy to which patients like Darwin responded. Central to Gully’s apologia for his profession is the notion of a natural sympathy between one organ of the body and another. According to this doctrine, the brain, for example, may be adversely affected by physical events elsewhere. Irritation of the stomach leads to stimulation of the blood vessels of the brain: these become congested or plethoric, resulting in a feeling of fullness in the head, impatience and irritability of temper, “apoplectic congestion,” “paralytic congestion,” hypochondriasis, and, in the worst cases, insanity or “drivelling imbecility.”[6] Pains in the shoulders or the head; chronic irritation of the liver; tic douloureux of the face, arms, fingers, or thighs; asthma or consumption; tetter, scurf, acne, psoriasis, and dandruff; tenderness and swelling of the feet; the exquisite pain of gout: all of these and many more may be blamed on the sympathetic effect of the ailing stomach upon the body and mind of the patient. At the furthest extreme of his acute new sensitivity, he may become so tender and transparent that he can actually feel a cloud passing in the sky; he may report changes in the wind during the night, or predict snowfalls ten or twelve hours before any other sign appears.

The action of cold water upon the body of such a patient consists precisely in setting up a kind of relay or feedback system between the inner organs and the skin. Water draws the blood away from lethargic or shiftless organs and towards the surface of the body. There the excess blood is dissolved, and the remainder returns revivified and ready to flush out the morbid matter that has blocked the body’s fine conduits and culverts. The same effect may be had, writes Gully, by adhering to a healthy diet, taking regular exercise in the fresh air, and refraining from intellectual activity. (Like Priessnitz, Gully seems to have considered reading and writing especially injurious to the brain, which perhaps explains why so much of his book is made up of lengthy quotations from certain pamphlets by his colleague Wilson.) Cold water, however, ensures a speedier recovery:

The appetite, rendered keen by the ensemble of the plan pursued, and especially by the water drinking, leads to the digestion of good food, for the processes all tend to the reduction of irritation in the digestive organs; the life in the open air perfects the blood formed from the food; all the processes tend to draw that blood towards the exterior surface and relieve the interior organs; the water drinking and exercise increase the chemico-vital changes of the blood which waste it; and, as the old morbid fluid dissipates, improved digestion is making a better, which is to bring about a healthier nutrition of the frame. It will be seen that the parallel [with diet, air, and exercise] is complete: and as the means of the water cure are only, as it were, an exaggeration and systematization of those to be found in the natural agents—food, air, and so forth, it may very properly be denominated the hygienic water treatment.[7]

One might plausibly assume that hygiene is at the heart of the hydropathic imagination, that it is the very purity of the water with which the patient is drenched within and without that ensures his or her recovery. But cleanliness as such is not exactly the metaphoric ideal to which the water cure aspires. Rather, it seems that it is the action or movement of water, rather than its rinsing or laving effects, that practitioner and patient hope to promote and to obscurely emulate, even ultimately embody. For sure, water as substance is symbolically opposed to the turbid, at worst alluvial, thickness of blood. It is contrasted too to all manner of oily or unctuous substances: in The Metropolis of the Water Cure, an anonymous account of a treatment at Malvern published by “a restored invalid” in 1858, we are told “there is nothing so likely to draw the gravy out of a man as the lamp bath. It is for all the world like being a fat goose before a slow fire.” A bathman attending one such patient, recalls the author, regularly wiped up “rich unctuous drops of spermaceous alderman.” But the fantasy at work in hydropathy is not strictly to do with the purity or corruption of a liquid: it is rather a question of how that substance moves within and around the body, and how that flow or filtration allows us to figure the body as an almost inorganic entity. The body is imagined as a medium through which water trickles, percolates, and seethes. It is pictured, in other words, as a kind of geology: composed of uniform strata rather than the gross entanglement of vessels and organs, a medium that can be soaked through and retain its integrity and strength. It is a vision that survives in the tiny schematic drawings of underground springs and gravel beds that appear on the labels of bottled water. We are not meant merely to admire the pure source of the product—we are also asked to believe that our bodies are as solid, porous, and consistent as a hillside somewhere in Yorkshire, Colorado, or Provence.

• • •

By the 1870s, the vogue for hydrotherapy had declined to the extent that it was only the eccentric and the elderly who still resorted to its rigors. For many of its early enthusiasts and later adopters, the treatment manifestly did not work. But the reasons for the slump are also inherent in the brief popular success of the practice: as hydropathic establishments flourished in the 1850s, they began to offer several sorts of ancillary treatment and diversion, such as mesmerism, homeopathy, clairvoyance, and electrical stimulation. Restrictions on diet and alcohol intake were gradually lifted, and even the temperature of the water used was subject to negotiation. Dr. Gully railed against the slipping of standards; in his Guide to Domestic Hydrotherapy of 1869, he wrote: “I have known a medical practitioner treat—and amuse—his lady patients by putting them into a tepid sitz bath containing a wine glass of port wine! varied occasionally by the addition of oatmeal.” In the end, however, it was Gully himself who finally and irredeemably corrupted the reputation of hydropathy. In 1876, aged sixty-eight, he was questioned at an inquest into the death by poisoning of a barrister, Charles Bravo. Gully and Mrs. Bravo had previously had an affair, while she was married to a man called Ricardo. Both Gully and the Bravos had settled in the town of Balham. A verdict was returned of murder by a person or persons unknown, but James Manby Gully’s reputation was in ruins. The Times opined: “a more distressing picture of the consequences of indulging unlawful passion has never been drawn.” Gully’s name was struck from the registers of all the medical societies to which he belonged.

- The terms hydropathy and hydrotherapy were used more or less interchangeably. “Hydropathy,” The Lancet pointed out regularly as the water cure grew in popularity, was an etymological absurdity—it denoted, literally, “water death.”

- E. S. Turner, Taking the Cure (London: Michael Joseph, 1967), p. 148.

- Their spread did not go unchallenged: in March 1842, The Lancet condemned hydrotherapy as having originated in “that hotbed of absurdities, Austria, where the crushed minds of men that cannot bear the healthful fruits of free investigation run riot in the extravagances of fantastic credulity or ignorantly strive to breathe life into the dead superstitions and one-idead theories of the Middle Ages.”

- Ibid., pp. 174–175.

- Ralph Colp, To Be an Invalid: The Illness of Charles Darwin (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1977), p. 41.

- James Manby Gully, The Water-Cure in Chronic Disease (New York: Samuel R. Wells, 1873), p. 19.

- Ibid., pp. 302–303.

Brian Dillon is UK editor of Cabinet and the author of a memoir, In the Dark Room (Penguin, 2005), which won the Irish Book Awards non-fiction prize. His writing appears regularly in such publications as Frieze, Art Review, Modern Painters, the London Review of Books, the Times Literary Supplement and the Wire. He is working on Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives, to be published in 2009.