The Origins of Cybex Space

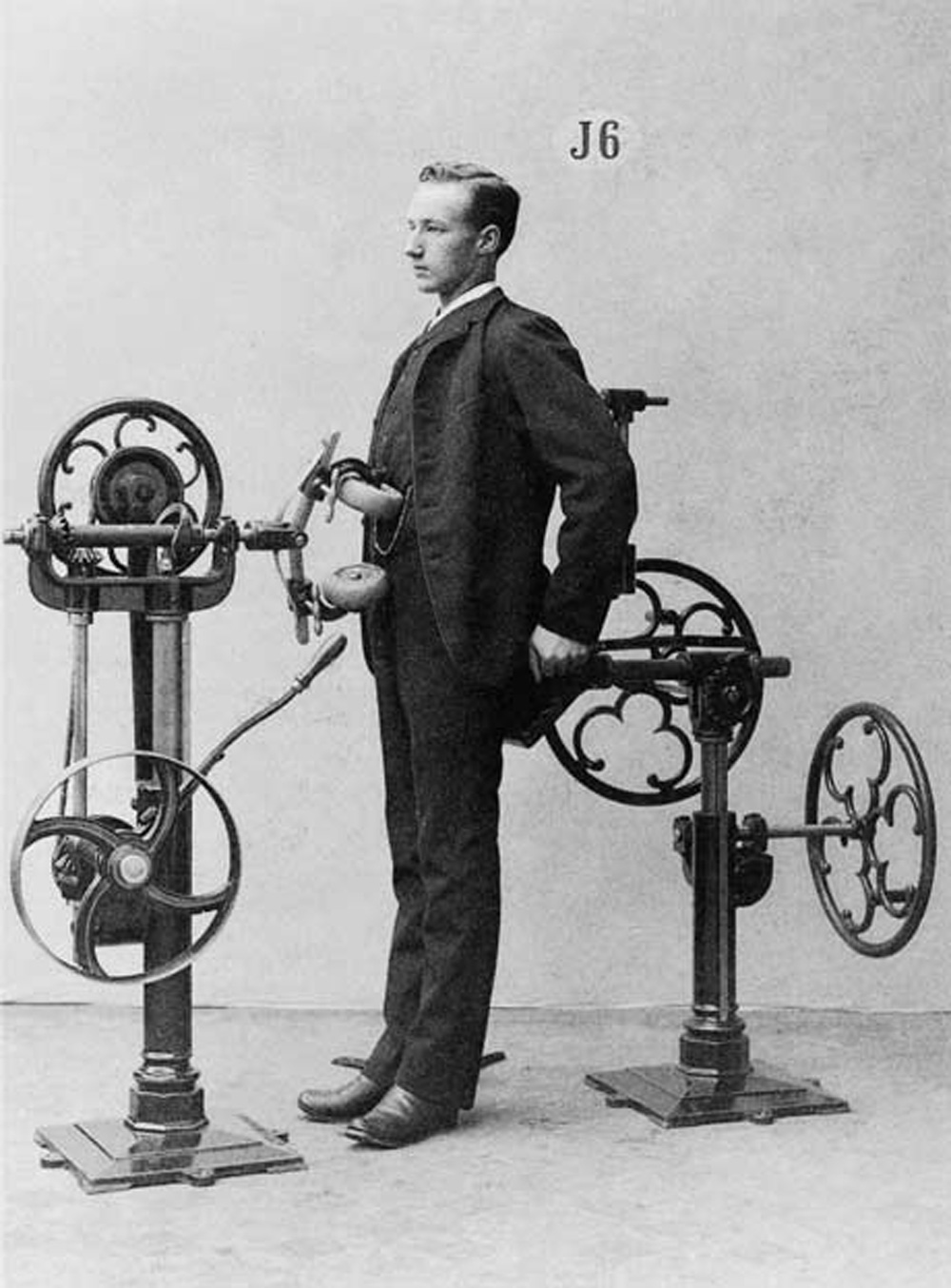

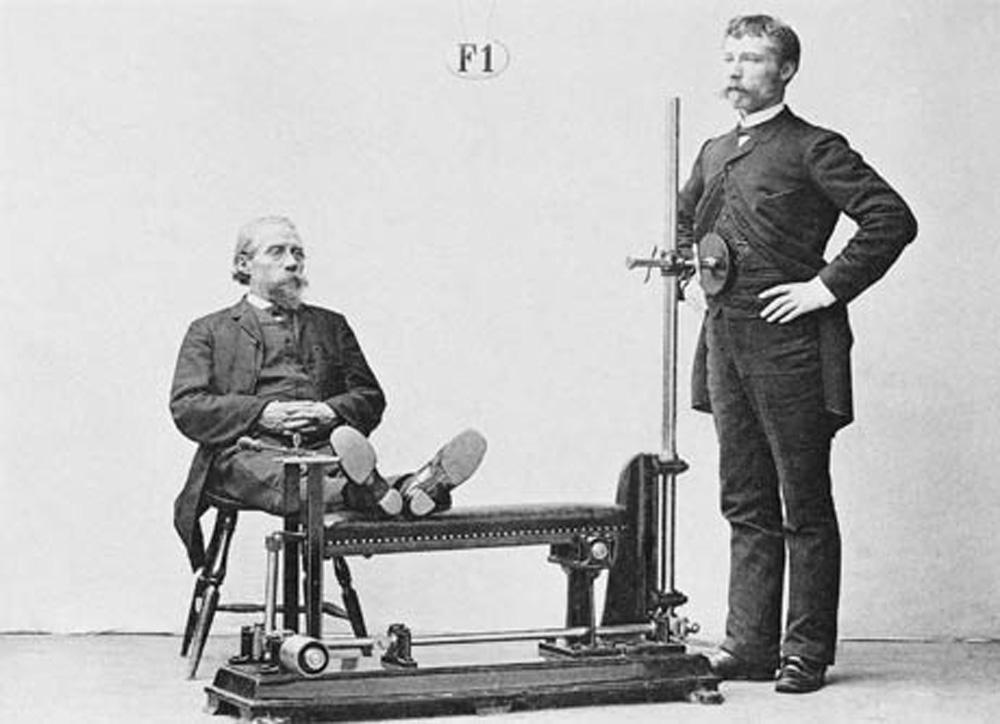

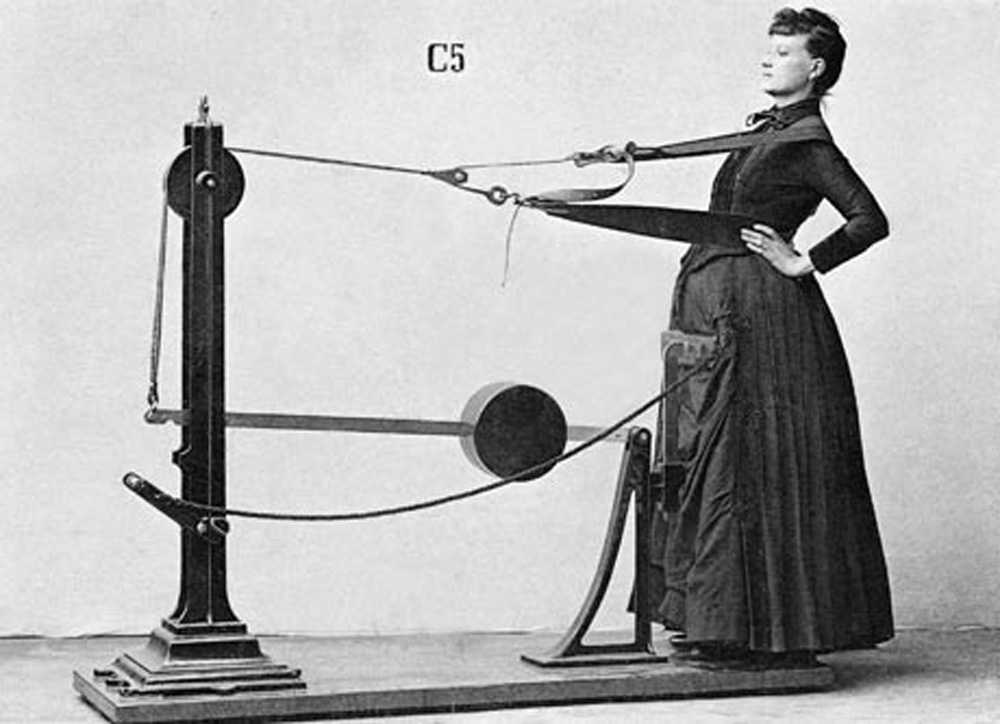

Gustav Zander’s amazing gymnastic devices

Carolyn de la Peña

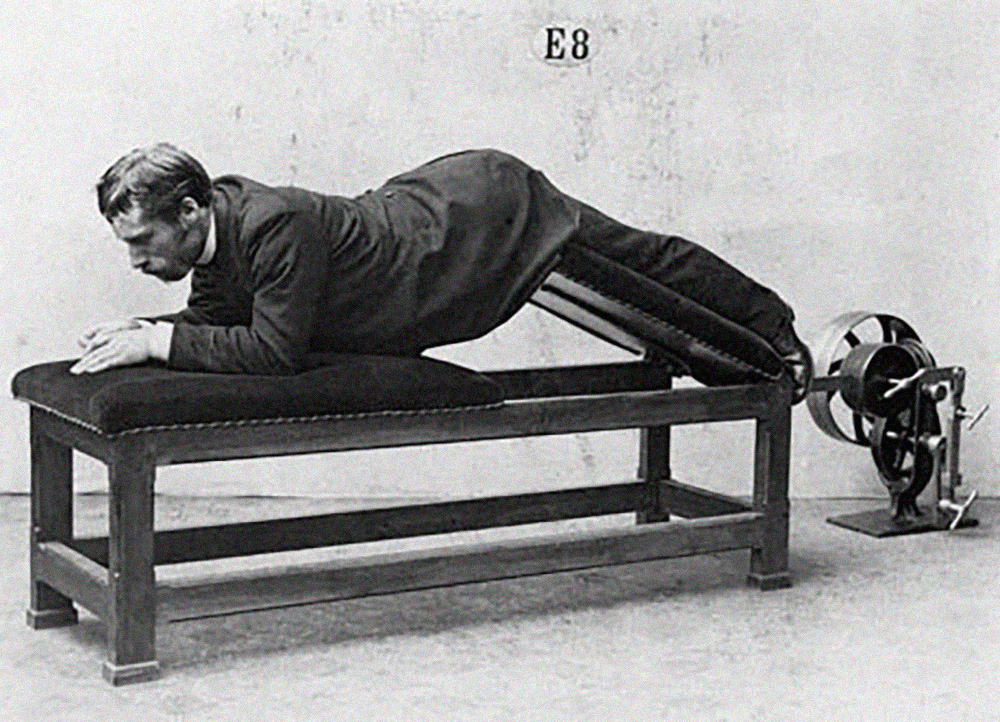

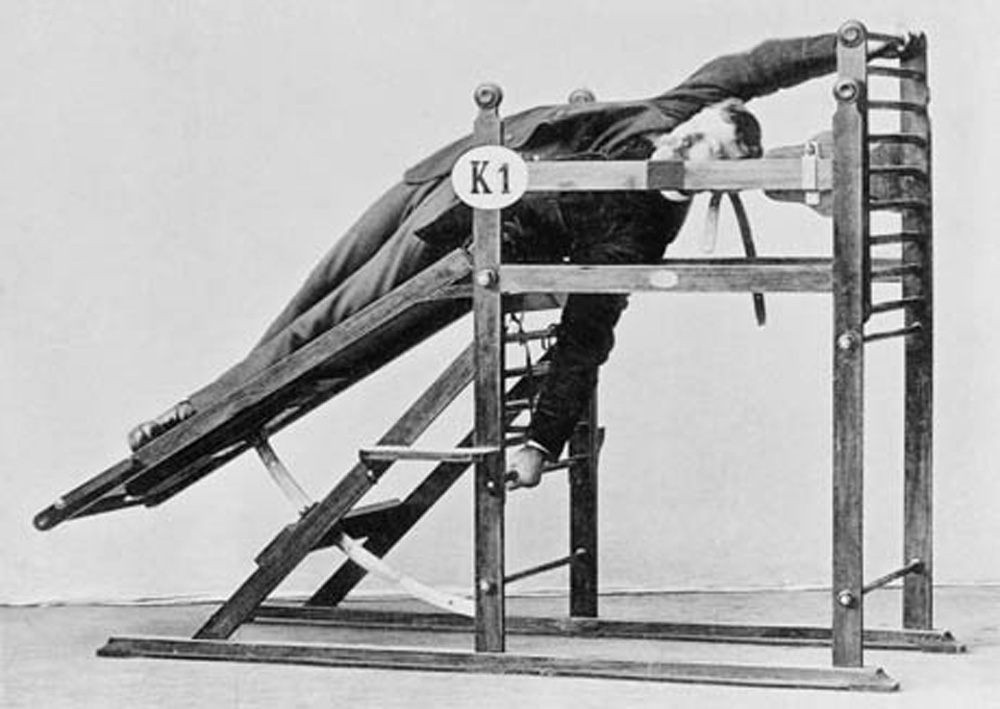

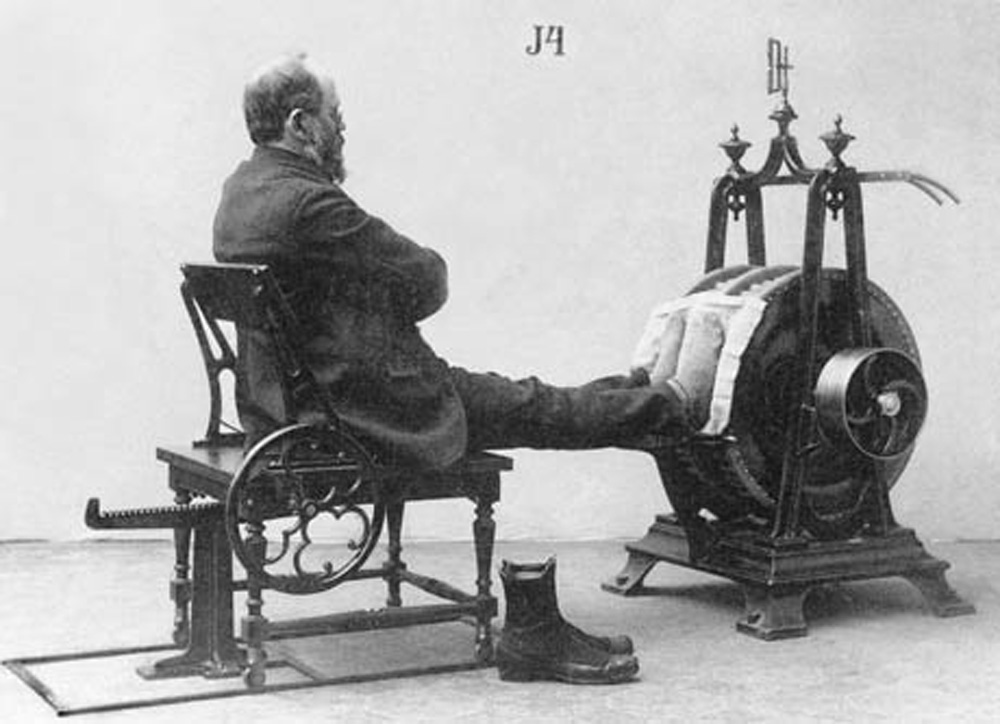

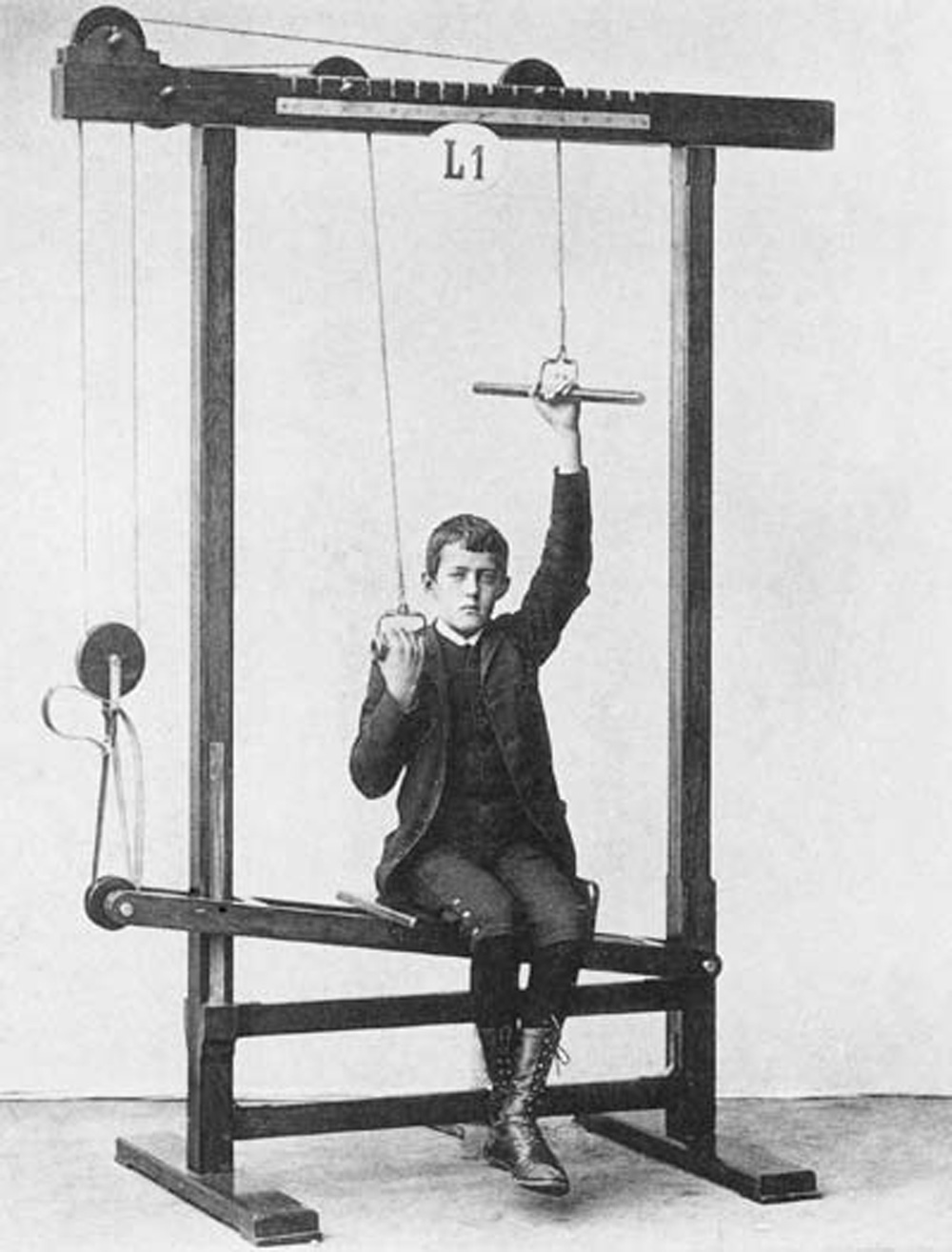

The Swedish physician Gustav Zander’s institute in Stockholm, founded in the late nineteenth century and stocked with twenty-seven of his custom-built machines, was the first “gym” in the sense that we know the word today. His mechanical horse was an early version of the Stairmaster, a contraption for cardiovascular fitness designed to imitate a “natural” activity. His stomach-punching apparatus evokes contemporary “ab-crunching” machines. What makes Zander so important, for anyone trying to trace the Cybex family tree, is what happened when his machines, created in a European cultural context, immigrated to the US in the early twentieth century. They are prototypes of the workout equipment now ubiquitous in American life.

In Stockholm, Zander’s institute primarily treated children and male workers. Supported by the state, it was equally accessible to those with and without means. The complex mechanized system was believed uniquely capable of correcting physical impairments brought about both by accidents of birth and by hard labor. A follower of Per Hendrik Ling’s movement cure, Zander argued that the key to health was not blood letting, purging, or strenuous acrobatics (other allopathic “cures” of the time). Instead, one needed to practice “progressive exertion,” the controlled, systematic engagement of the body’s muscles in order to build strength.

In the US, however, Zander sought and found a very different clientele. His award at the 1876 Centennial and International Exposition in Philadelphia for best mechanical design provided a launching pad for marketing Zander machines as upscale devices for the rising American business class. His machines offered, Zander explained to an American audience, “a preventative against the evils engendered by a sedentary life and the seclusion of the office.” In fact, Zander claimed, there was no treatment quite so appropriate for these emerging white-collar men (and their wives) as his mechanized system. While doctors’ pills and potions might be easier to procure and quicker to ingest, the “increased well-being and capacity for work” gained by those who used his machines, he argued, was “rich compensation for the time bestowed on them.”

By the early twentieth century, extensive collections of Zander machines could be found at elite health spas such as Homestead in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and at private institutes such as the one Zander set up near Central Park in New York. Access to these health machines was a mark of status at the turn of the century. Health spas and gymnasia were not subsidized by the state as they were in Sweden, and the American working class would not have been able to afford the fees required to receive Zander treatments. Nor were the working class thought to need such treatments; their “hearty” bodies were not yet impaired by the sedentary habits of affluent modern life. In mechanized workouts, white-collar Americans pumped up their own superiority. By declaring that “fitness” equaled a perfectly balanced physique, rather than the ability to perform actual physical tasks, body power was shifted from laborers to loungers.

If to our twenty-first-century eye, Zander’s horse rider hardly looks “fit,” one must see her in context. Not only is she riding a horse (itself a mark of status), but one whose rhythms had been perfected by science. Her mechanical horse, hooked up to an engine, delivered a precise set of trots per second and provided her with a workout that had no equal. The same applies to the suited gentleman receiving his requisite abdominal punches. Once “health” was separated from tasks and turned into “tone,” machines became a way for those with means to define their bodies as superior.

In this respect, Zander’s machines do resemble our contemporary Stairmasters, Cybexes, and Pilates devices. Consider how much you pay, if you do pay, to go to the gym. Consider that complicated regimen that the instructor puts you on at your first “complimentary” consultation: fifteen reps on the thigh extender, thirteen on the bicep pulleys, two sets of ten on the abdominal flexers. Consider the ways in which gyms, especially elite gyms, still function as pick-up joints for the affluent and beautiful. Of course, gyms are far more available—and affordable—than they were in Zander’s day. Even so, the time to spend working on each muscle and the ability to separate muscular labor from actual physical work continues to bestow a particular superior status on those who sculpt at the gym over those who are merely strong. We are, in other words, still “suiting up” by going to the gym.

It’s in the expressions worn by the people in Zander’s advertisements that the real distinction between workouts of 1908 and workouts of 2008 can be found. Take the horse rider. She sits casually astride the machine, one arm out holding the “reins” on her anthropomorphized device. Her body leans slightly back. Her eyes gaze up at the camera, almost ecstatic, head thrown to the right a bit, a slight smirk on her face. She wears hose and heels, and the strap of her dress has fallen off the shoulder. The abdominal man is more formal but equally relaxed: though his posture is erect, he looks straight ahead, expressionless. His toes extend slightly in the air, revealing that he is actually somewhat reclined—his weight sinks into the device behind him.

Their experiences bear little resemblance to what happened to me at the gym this morning. My twenty minutes on the elliptical trainer were anything but relaxed, reclined, or serene. Instead, I struggled to keep pace, manically following the “terrain” ahead that was mapped out on the monitor (hill climb; level four, two minutes; level six, five minutes; level eight, etc.) as I clumsily followed instructions to move my arms forward and back while my legs were told to go in the opposite direction. Next to me, on all sides, were other people similarly focused on fulfilling the demands of their machines. Stair climbers, treadmills, reclined bikes, erect bikes, elliptical trainers with movable rowing arms, elliptical trainers without arms. In all, there were eight different machines to choose from just among the cardio devices. And each had an intricate, and individual, set of demands it required from users.

Why do our machines demand so much of us? And how might Zander’s, placed in their own cultural moment, help us understand our apparent desire to capitulate to their demands? In fact, Zander’s machines succeeded precisely because they demanded little of their users. “All you need to do is sit down in the saddle,” explained the first American guide to Zander’s “horse,” “and the mechanical steed gallops away with you.” The electrically driven abdominal and horse machines were designed to administer force to users, not to require force from them. In part, this vogue for passive machines can be attributed to the American desire for convenience. This was not limited to mechanized exercise: Mark Twain wrote of his enthusiasm for osteopathy (the systematic manipulation of the bones and muscles) because, “it is vigorous exercise, and others do it for you.”

More important, however, was an understanding of the body as a system of potential energy, energy that could be released only by regular and perfectly controlled force. This was the theory behind massage, commonly used at Dr. John Harvey Kellogg’s Institute at Battle Creek to revitalize worn nerves and tired muscles. Human variability, however, prevented perfect uniform force from reaching the body: one masseur might be stronger than another, one might tire while treating the legs before reaching the feet. Zander’s machines eliminated those threats: the machine never tired. As the brochure for the abdominal machine explained, the true benefit of being hit by a set of perfectly rhythmic oscillating leather disks was that “sunken vital energy is raised.”

But was it? Massage, which is what these machines provided, can relax and invigorate, but it does not actually release hidden energy in the body and bring it to the surface. Muscle tone was improved, but not dramatically given the passive pose struck by most patients. The true benefit of Zander’s machines, I would argue, was what one promoter termed their “mental effect.” This, explained one American brochure, was “produced by the huge and complicated machines,” which it described as “a valuable adjunct.” In an age of “gears and girders,” the opportunity to put one’s body in the path of new, large, and powerful electric machines may in fact have been part of the benefit. Technology was anxiety-provoking, unreliable, and mysterious. In this context, stepping in front of a mechanical punching partner and riding the trotting horse—and emerging not only safe but “healthy”—would have been a rush. Zander’s patrons derive their serene pleasure from placing themselves at the mercy of the machine.

Zander’s bulky machines disappeared by the 1930s, replaced by smaller, more compact equipment and eclipsed by new priorities brought by war and depression. Today, we find ourselves sweating away on our own updated “Zander machines.” Is it possible that when we select from complex menus of simulated terrain options, struggle to keep pace with the machine’s demands, and precariously balance on multiple moving parts, that we are needlessly complicating our own mechanical interactions for similar “mental effects”? In an age of iPod soundtracks, customized Amazon suggestion lists, and OnStar GPS that enables vehicles to practically drive themselves, might we be looking for active complexity for the same reasons our Zander predecessors sought to be passively content?

See press on “The Origins of Cybex Space” on Livestrong.com, Preliminary Study: RSI – T, and The Atlantic.

Carolyn de la Peña directs the Davis Humanities Institute at the University of California, Davis, as well as the school’s Program in American Studies. Her research and teaching interests focus on popular technology and science, material and business cultures, gender, and food. She is the author of The Body Electric: How Strange Machines Built the Modern American (New York University Press, 2003) and the co-author of Rewiring the “Nation”: The Place of Technology in American Studies (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.