The Gothenburg Leviathan

Into the belly of the Malm Whale

Cecilia Grönberg and Jonas J. Magnusson

No family of mammals is more difficult to observe or more incompletely described than whales, wrote zoologist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier in The Animal Kingdom (1817). And even Cuvier, who for a long time dominated the fields of classification and comparative anatomy, could only offer the following partial definition of the creature: “Cetacea consists of animals without hind-limbs.”

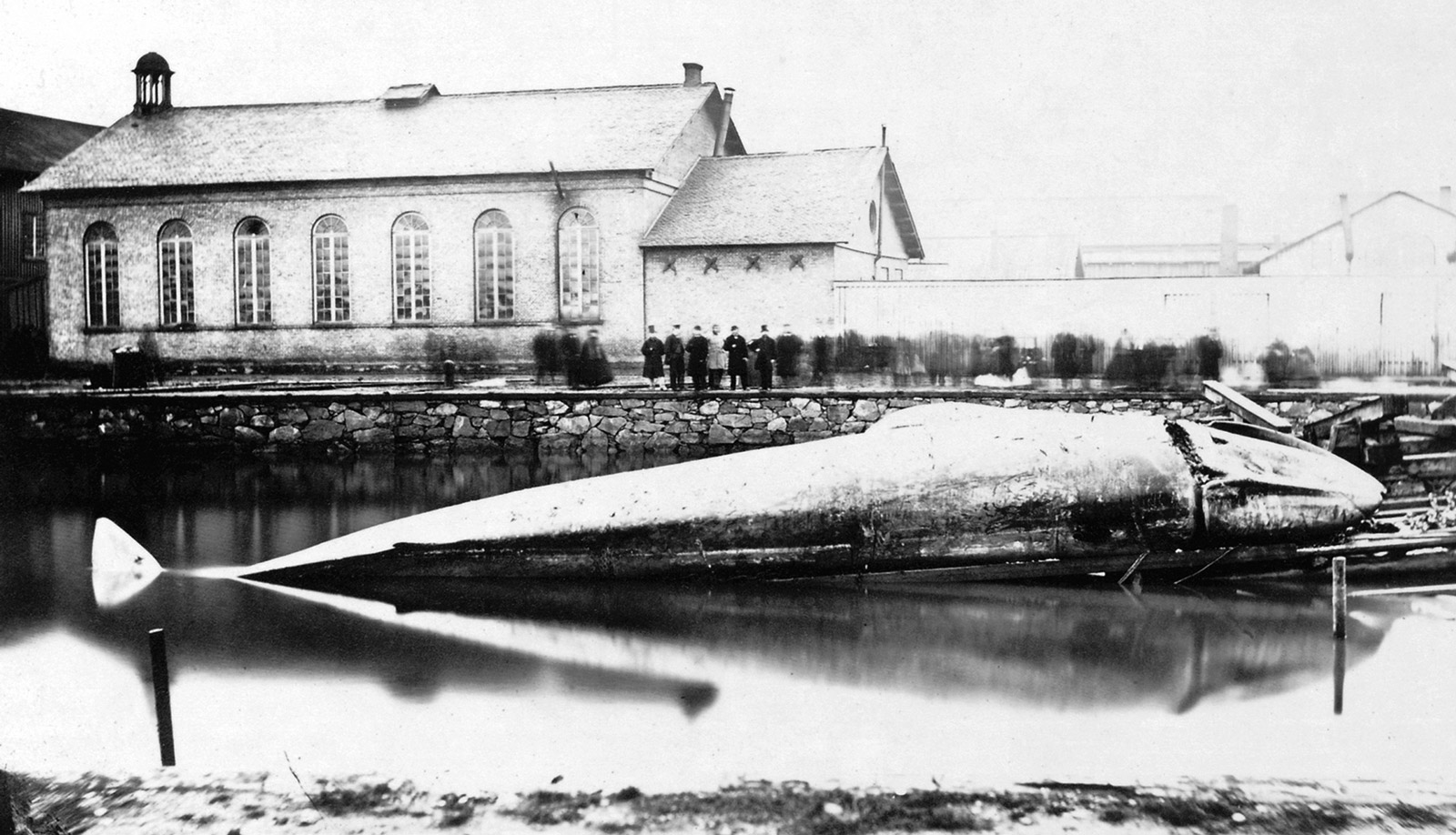

Cuvier’s assertion about the extraordinary difficulty of describing whales could serve as an epigraph for one of the most remarkable, but today largely forgotten, books in the history of both Swedish zoology and photography—Monographie illustrée du baleinoptère trouvé le 29 Octobre 1865 sur la côte occidentale de Suède (Illustrated Monograph on the Balænoptera Whale Found on the West Coast of Sweden on 29 October 1865) by August Wilhelm Malm. This lavishly illustrated 133-page folio, published in 1867, documents the killing, towage into Gothenburg, scientific measurement, and preservation of the seven-month-old, sixteen-meter blue whale that beached outside Näset, south of Gothenburg in 1865. Malm, with great difficulty, transformed this whale into the renowned Malmska valen (“The Malm Whale”), a unique construction that is still the jewel of the Gothenburg Natural History Museum and one of the most popular museum artifacts in Sweden. The Malm Whale is the only stuffed blue whale in the world, and the only one that—thanks to a moveable upper jaw that is still flapping 137 years after the animal’s death—allows the museumgoer to enter the whale’s belly and visit a lounge furnished with benches, red carpeting, and walls lined with blue muslin and decorated with yellow stars. (When the museum commemorated the whale’s hundredth birthday in 1965, more than 11,000 people visited it during the ten-day celebration. The Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet reported that American tourists were especially interested, entering “the belly of the whale for religious reasons—they want to follow in the footsteps of the prophet Jonah, and they have their pictures taken when deep in prayer.”)

Monographie illustrée was a deluxe edition that Malm, curator and taxidermist at the Gothenburg Museum from 1848 until his death in 1882, hoped would secure his reputation in the annals of science. The cost of the book, printed in fifty copies on the finest possible paper, was defrayed by state grants, but Malm, also eager to educate the public, had already published a thinner “people’s version” in 1866 at his own expense: Några blad om hvaldjur i allmänhet och Balænoptera carolinæ i synnerhet (Some Notes on Whales in General and on Balænoptera carolinæ in Particular). This popular handbook sold for only twenty-five öre when the whale was exhibited in Gothenburg and Stockholm, and a German version was produced to accompany the international tour that was planned for Copenhagen, Hamburg, Berlin, Paris, and London among other cities, but which ran aground in Germany.

In Några blad, Malm describes his whale as belonging to a “previously unknown species,” and christens it Balænoptera carolinæ after his wife. What Malm does not know is that the whale is not a new species, but simply a young blue whale (Balænoptera musculus) whose body and skeleton have not yet undergone the dramatic changes in proportion that occur with maturity. Malm is mistaken about the whale, but at the same time he becomes the originator of a historically singular creation, a taxidermically unique specimen. His outsized vision—of salvaging not only the skeleton, but the entire whale—requires that Malm risk everything, privately and professionally.

As he himself puts it, rather immodestly, in Några blad om hvaldjur:

Despite the favorable location of the whale, I immediately realized that little was to be harvested for science or for the museum, if the work was undertaken in situ. For me, such a procedure would however have been more convenient, considering my certainly not strong constitution; and if I would have contented myself to salvage as much as my predecessors had rescued, which, in case I would have wanted to proceed on such a path, easily would have been possible to do already on the first day, by means of chopping off one part or another from the body. But I was not going to content myself with such trifles, even if the value of what was salvaged could have amounted to 4–6 times the cost of the purchase. No, no matter what the cost, I would have the colossus, still un-mutilated, up on shore! It was not until then that I ... would be able to claim to “have the entire whale in my power.” Not until then would the whale be fully available to science; of value for an attempt to reproduce the animal in its entirety.[1]In his popular handbook, Malm, as the title suggests, wants to move from the general to the specific, from talking about whales in toto to exclusively talking about one whale, the one that ran ashore outside Gothenburg in 1865. This is the whale of his life, and in Monographie illustrée Malm gives in to his obsession and treats this lost creature with a thoroughness that defies all expectation, resulting in a descriptive excess that becomes a piece of involuntary literature.

• • •

The story told in Monographie illustrée begins with the fisherman Olof Larsson, who is hunting small game outside the village of Näset on a windy Sunday morning in October 1865. Around nine, he catches sight of “something unusual” not far from the shore. At first it appears to be the remains of a wrecked ship, but when he reaches the shore where the object lies some forty meters out in the sea, he discovers a live animal, visible about twenty-five centimeters above the surface and struggling to get loose. Larsson has never seen a whale before, but nevertheless he recognizes the creature. He hurries to fetch his brother-in-law, Carl Hansson, who lives two and a half kilometers away, and returns directly to the whale. Two days later, when Malm arrives on the scene, Carl Hansson explains what happened next:

Since my brother-in-law said that “the whale was lying there struggling with all its strength and loudly spouting water high into the air,” and since I, on my travels on the North Sea, had seen a couple of these dreadful beasts, I chose a large boat thinking that if the whale wanted to swallow it, it would not succeed. … We approached by tacking toward the monster until we were eighty to ninety feet from it, so that we could observe it. … Olof then saw something shiny on the side of the whale’s head, two inches above the surface of the water. Occasionally the whale moved this shiny thing, in the same way a human would. It was obvious that it was the eye. The whale was blinking its eye, and we decided to poke it out so it would not be able to see us. After that we reckoned we would succeed in killing it. The knife was stuck in and the boat hook [to which the knife was attached] sank in two feet. The blood was gushing a couple of inches above the surface of the water; it then poured like this for half an hour, in the same way as when one punches a hole in a barrel of beer. … With the help of harpoons and rope, we managed to attach one end of the hawser to the skin on the side of the head of the beast. In this way we held the whale back when it tried to get loose, and I believe this contributed to bringing it even closer to the shore. … I then climbed up on its enormous head, and with an axe I cut a gash behind the two holes it was breathing through. … The whale was very slippery to hold on to, and since it was twitching violently, … I had to get back into the boat again on several occasions. … I cut it like this with the axe from ten o’clock until half past three in the afternoon. … Now it was evening. We returned home, but did not tell anyone about our find. …When we arrived … the next morning, the water had sunk considerably, so that the whale was visible more than one foot above the surface of the water. … I stabbed it with a scythe deep in the eye and belly. … It was easy to see that the whale was losing more and more strength. … It was eleven o’clock in the morning. The whale was immobile, and still bleeding at three in the afternoon, but then it gave us dramatic evidence of its strength. Suddenly it raised its body, leaning on its head and tail, like an arc, altogether over the surface of the water. It then threw itself back on the bottom, so that the water was divided with a terrible rumble. Due to this motion the whale moved another eighteen feet closer to the shore; and then it did not move any more.[2]

After this follows Malm’s report of his own encounter with what he has been led to believe (based on a description supplied by Carl Hansson, who was looking for a buyer for his find) is a minke whale but which, to his great joy, turns out to be a “colossal Balænoptera.” He examines, measures, and makes drawings of the still fresh animal and registers that it has, in addition to the cuts and wounds inflicted by the brothers-in-law, also been manhandled by spectators who have taken “souvenirs” home. He finds one of its eyes in the sea, whose icy temperature (in combination with the fact that “the blood had been pumped out, just as the intestinal canal had been emptied during the long death struggle”) had contributed to slowing down the process of decomposition.

Malm decides to purchase the colossus and visits the Gothenburg magnate James Robertson Dickson in an attempt to obtain the 1,500 crowns that its killers are demanding. In the evening, he performs a microscopic investigation of samples of skin, muscle fiber, blood, and other elements that he has brought home with him. The day after, November 1st, the deal is closed, and Malm immediately gives an engineer at Lindholmens Mekaniska Verkstad the assignment to “take all necessary measures to pull the whale loose, transport it to the city, and haul it up on the Lindholmen slipway.” Two steamboats and two coal barges are sent to the place, but it is not until two days later, with the help of a third and more powerful steamboat, that they finally succeed in getting the now stinking whale afloat. It is towed into Gothenburg and arrives, followed by hundreds of curious onlookers in small boats, at Lindholmen at two in the afternoon. Encouraged by the enthusiastic public, Malm climbs up on the back of the carcass and gives a short lecture on the most important episodes in the history of whales, seizing the opportunity to illustrate his speech “with the aid of the colossus itself.”

Early the next day, Malm begins to study the whale in earnest. There is no time to waste, since the curious crowd will be back in an hour or two. With the aid of a goniometer and other instruments, he measures every part of the whale. Around ten, the photographing of the whale begins, and it continues as long as the light allows. The day is coming to an end, and it is high time to quarter the animal (the abdomen and lower part of the head are already swollen as a result of decomposition). Malm is, however, content to open the body in different places in order to release gas and water mingled with blood; the smell is unspeakably sickening, and for a moment makes the pressing crowd withdraw. Darkness falls, and everyone, except for the hired watchmen, leaves for home.

The following day, Malm is back early, followed by “ten strong butcher’s assistants and more than twice as many other workers,” in order to “cut up the magnificent beast before the decomposition progresses further.” It is now Sunday again, one week after the discovery. Malm and his “army,” which has been promised free access to distilled beverages, is faced with the problem of how to cut the animal up. Malm knows very well what he must do, but where should he begin? It is on this decision that “the richness or poorness which will be harvested for science depends.” It is above all a question of the skin, “shining like a mirror and beautifully marbled.” At first, Malm intends to take only a couple of feet of the skin to preserve a memory of the exterior of the whale, but at the very last moment, standing on a ladder between the back of the whale and the left fin, he makes a fateful decision—to preserve everything.

Malm himself makes the first incision with a scalpel, and then the butchers take over with their big knives. The skin-blubber mass, with a thickness ranging from124 to 298 millimeters, is quickly removed, and the butchers then work their way smoothly inwards (along the spine, the warm meat has the consistency of purée). The intestines are removed and cleaned with a fire pump, and after this follows a pause for half an hour while the internal parts of the whale are photographed. Then the knives are taken up again.

Around three in the afternoon, an exhausted Malm is overcome by severe nausea. After supervising one last photograph, he is compelled to leave the scene—an absence that proves fateful. It is now that several parts of the whale disappear, never to be found again. On the whole, these are small losses, but painful for someone who wanted everything. To keep the onlookers, who have paid twenty-five öre each to be there, at a respectful distance from the whale, Malm has put up posters, but neither they nor the police on the scene are capable of preventing thefts of pieces of bone and skin. The crowd approaches the whale for other reasons as well. Two ladies throw themselves forward, “driven by an uncontrollable desire to verify if the passage of Jonah through the throat of the whale was actually possible.” A candidate in theology questions whether it is appropriate to be working on a day of rest; Malm, aware that cutting up the animal could not have been postponed, can only answer “Yes.” By now, night has fallen, and the remains of the whale are loaded onto barges in the dark.

The long strips of skin and blubber are transported, along with the tail, arms, and intestines, to the Gothenburg Museum (the intestines are kept in barrels in the yard, where the tail and fins are arranged on stools and boxes and photographed). Parts of the whale, including the heart, one eye, larynx, rectum, and parts of the intestines, are preserved with glycerine and alcohol. The pieces of skin are stored on the floor according to an elaborate system, while the skeleton is being boiled at another location. Back in the museum, eight fishermen remove 3,400 kilograms of blubber from the skin, which is hung up on wooden frames. The skin is then treated with specially manufactured brushes (“a radical way to make the skin evenly thick and to tear away the cellular tissue and remove a large part of the oil, without causing the skin to lose anything essential of its strength”) to reach a thickness of roughly a centimeter—a process that will take almost three weeks. Simultaneously, an equal number of fishermen are working in the yard of the museum to clean the boiled skeleton. Every part is labeled with copper and brass pins so that it can be put back in the right place. In the museum, the baleens are salted while waiting for the wooden jaw in which they will be mounted. A sculptor produces a tail and fins of wood, which are dressed with the processed version of the skin. This initial phase is completed on the evening of 22 November.

Using the numerous measurements, photographs, and sketches that he has made, Malm makes a 1:10 scale drawing of the animal and then, working for three weeks with an engineer and a sculptor, produces a model in clay. In the middle of December, Malm orders a workshop to use the model to produce the smithwork necessary for an actual-scale frame to be built out of spruce; the patched-up skin is then to be drawn over this construction. To facilitate future transport of the reorganized whale, this construction is made in four detachable sections (ranging from three to five meters in length). The head is a veritable sculpture, to which the baleens have been attached. The neck is equipped with hinges, allowing the jaw to be opened “so that one can approach and closely observe the baleens from the inside, as well as the rest of the interior of the mouth.” And, “since many people might find it interesting to advance all the way into the belly, which is three meters high, some decorations and installments are made for the comfort of the visitor.” The skin, which over the winter has been processed with salt, fat-absorbing sawdust, and pulverized pipe clay, is rinsed with water, coated on the inside with a saturated arsenic solution, and finally fixed to the wooden frame with the aid of 30,000 zinc and copper pins. By mid-April, the skin has begun to dry, and it is coated with arsenic. As the crowning glory, an additional layer of mercury chloride is added, and then a layer of transparent copal varnish.

In order for “persons who are not initiated in science to see what is false,” Malm chooses to replace the parts of the skin that have been ruined by Larsson and Hansson (as well as by “the animal itself during the struggle,” the process of getting it afloat, not to mention indiscreet bystanders) with wood, instead of a more skin-like material. This decision might make Malm seem radical for his time, but it could have simply been a maneuver to divert attention from the real crack in the construction, something that Malm simply mentions in passing as “a small strip of wood” on the belly of the whale. Malm attributes this to the fact that the skin “had shrunk a little, … so that it was only by applying force that it would have been possible to bring the pieces together.” This is a qualified truth, for in fact it seems that dressing the whale with skin, which Malm presents as a more or less smooth process, is actually a source of huge friction. Malm certainly measures the animal minutely, but since it is not possible to turn the giant around, the girdle measurement can only be taken on one side, from the center of the back to the center of the belly. This should give half the circumference. But the whale has flattened on the underside and swelled on the upper side, possibly due in part to the gases released by putrefaction. The half-girdle measurement is thus a little too big. Nobody reflects upon this when the armature is later built. But when this expensive wooden construction, on which the processed skin will be mounted, is finally set up, the whole project almost sinks. Malm starts to attach the skin, but it then turns out that the fin on one side is situated far too low, while the other fin appears far too high up, on its back. The body is too wide over the abdominal part and the skin does not suffice. Malm despairs and gets a fever. But then A. J. Malmgren, a practical fellow who is a taxidermist at the museum and a former seaman, asks if he can give it a try. He starts out from the center of the back, which indeed causes the fins to sit a little high, and leaves a gap, five meters long and sixty-five centimeters wide, under the belly between the skin on the left side and the skin on the right. But on the whole it looks symmetrical, and the slit in the belly is then filled with paneling.

This gap can be easily seen even today; all the more peculiar, then, that newspaper reports from the time about the preparation of the Malm Whale are so reticent regarding the error in the construction. “All measurements,” Norra Hallands Tidning declares on 21 March 1866, “were so precisely taken and the model executed with such precision, that when the skin, which first went through a tanning process, was put over the wooden frame, the dimensions corresponded completely.” This amounts to a veritable “cover-up”—in reality there is still this undeniable black rift, a crack of darkness through which all the light leaks into infinite abysses.

This article is a revised excerpt from Leviatan från Göteborg. Paracetologiska digressioner: Malmska valen, Göteborgsvitsen, Jona-komplexet och Moby Dick (Glänta Produktion, 2002).

- August Wilhelm Malm, Några blad om hvaldjur i allmänhet och Balænoptera Carolinæ i synnerhet (Gothenburg: self-published, 1866), pp. 16–18.

- August Wilhelm Malm, Monographie illustrée du baleinoptère trouvé le 29 Octobre 1865 sur la côte occidentale de Suède (Stockholm: P. A. Norstedt & Söner, 1867), pp. 1–3. All further citations are from this book.

Cecilia Grönberg is a Swedish photographer. She is the co-author of Leviatan från Göteborg (Glänta Produktion, 2002), Omkopplingar (Glänta Produktion, 2006), and Witz-bomber och foto-sken (Glänta Produktion, forthcoming). She is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in the Faculty of Fine Arts at Gothenburg University, working on a dissertation on photography, montage, layers, and copying.

Jonas J. Magnusson is a Swedish writer and translator. His books include Jag skriver i dina ord (Lejd, 2000), Leviatan från Göteborg (Glänta Produktion, 2002), Omkopplingar (Glänta Produktion, 2006), and Witz-bomber och foto-sken (Glänta Produktion, forthcoming). He is one of the editors-in-chief of the Swedish magazine OEI www.oei.nu.