The Tattoo Solution

A zag, a zig, a beast, a grid, a swirl, a sword, a word, a Lord

George Prochnik

The universality of tattooing is a curious subject for speculation.

—Captain James Cook

That much is obvious. Human beings believe the ecology between what’s outside and inside is off and the epidermis is the best place to begin redressing this imbalance. The universality of tattooing Cook pointed to reflects the universality of the knowledge that we are not made in our own image. Whatever we might be, we look down at our bare skin and know there’s been a mistake, an omission. This unruly fabric in which we’re so wrapped up—this, anyway, is not it.

The truly radical step taken by the Hebrew Bible was not to posit that there was one God—the short-lived monotheistic worship of the sun god Aten in Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty is only the best-known precedent—but to notify all Adam and Eve’s brood: “You’re right, you don’t look like yourself. You look like Me.” We are all made in God’s image. It sounds considerate and democratic, but what it means in practice is that our skin is not private property. The surface of our flesh is like the plot of grass in front of some corporate headquarters. In relation to our skin, we are all but franchisees of Yahweh, Inc. Which helps explain why the rabbis introduced the world’s first proscription against self-mutilation. As does the fact that the surrounding idolaters were riddled with tattoos, and that the ancient Israelites had become enamored of cutting themselves as a sign of mourning.

Countless other examples of very early tattoos exist everywhere from the North Pole to the jungles. It’s as hopeless to try and determine when tattooing started as it is to pinpoint where it originated—it began wherever and whenever people began behaving more or less like we do. “I am that which I am,” God drily quipped. We fire back from the Tattoo Parlor of Babel: “I am that which I am not.”

Some historians of tattoos opine that the practice developed from body painting—which in turn began when primitive peoples, observing how a creature’s animation drained away with its blood, sought to cake their bodies with this vitality. The first instances of permanent body marking were probably brought about through scarification, which might have evolved as an effort to freight with meaning, or at least aestheticize, scars caused by the preferred forms of prehistoric medical treatment: blood-letting and related extractive operations (cutting, burning, cupping) to remove demons and the like. Or—apropos the Iceman’s corpse—the primordial tattoos may themselves represent a form of medical therapy. Early in the twentieth century, the American Anthropologist averred that tattooing began with the treatment of wounds “by rubbing in soot, ashes, drawing thread through the opening made by a needle. … Out of this came rubbing color-substances and finally the process of tattooing as we have it.”[2]

But the question is less one of process than purpose. Medical, magical, religious, aesthetic, punitive, mnemonic, or for sheer sport—when it comes to tattooing the answer is always all of the above. There are so many reasons people put forward for why they tattoo themselves that eventually they all start to sound like justifications after the fact. If the blank canvas drives the artist crazy, blank skin brings out the artist, or at least the graffitist in everyone. We tag ourselves to show we were here.

The barbarians [Picts] usually swim in these swamps or run along in them, submerged up to the waist. Of course, they are practically naked and do not mind the mud because they are unfamiliar with the use of clothing ... They also tattoo their bodies with various patterns and pictures of all sorts of animals. Hence the reason why they do not wear clothes, so as not to cover the pictures on their bodies. They are very fierce and dangerous fighters ... Because of the thick mist which rises from the marshes, the atmosphere in this region is always gloomy.[3]

But the whole scene smacks of theatrical shivers. Gangs of naked warriors who cared so much about showing off their bestiary of body art that they’d rather freeze than toss on a furry pelt while sprinting through the bitter fog rising off primeval Britannia’s icy bogs? Who could have seen anything in such a mist? Any self-respecting Roman’s take-away from the scene would be simply, “Get me back to sweet Trastevere.”

In fact, Herodian was writing two hundred years after the events he describes, and he himself never set foot near brutal old Britannia. Maybe the Picts were pricked. Maybe not. Either way, we can say with confidence that they didn’t start any fad for tattoos. Scratch the Caledonian solution. Jump forward 1,800 years. Now the fogs begin to lift.

In most accounts, the pair’s return to England with their tattoo tales, tattooed Maori heads, and perhaps a tattooed fellow sailor or two, triggered the western trend. They’re also credited with having introduced tattoo into the English language, as a derivation of ta, which means “to knock” or “to strike” in many Polynesian dialects. The catch is that tattoo in the sense of a military display had been in use in England since the mid-seventeenth century, deriving from the Dutch taptoe, meaning “tap to,” literally “turn off the tap”—the signal that beer barrels were shut and soldiers at the tavern had to return to their quarters for the night.

Nonetheless, there’s no question that after Cook’s voyage, the tattooed sailor became a transatlantic commonplace. The marks began as seductive travel souvenirs and amulets against ill fortune, but soon expanded to encompass a wide repertory of icons. Melville writes in White-Jacket, his novel about serving in the US Navy, of how among the ship’s company there were invariably those who “excelled in tattooing, or pricking, as it is called in a man-of-war. ... Each had a small box full of tools and coloring matter; and they charged so high for their services, that at the end of the cruise they were supposed to have cleared upward of four hundred dollars. They would prick you to order a palm-tree, an anchor, a crucifix, a lady, a lion, an eagle, or any thing else you might want.”[5]

By the early twentieth century, the US Navy was forced to expend volumes of ink on hygiene manuals prepping medical officers for the task of notating sailors’ tattoos on ID cards. The instructions suggest an elaborately proliferating stock of designs. “In the case of devices composed of two or more figures, the component parts should be named, e.g., ‘Heart, cross, and anchor,’ not ‘Faith, hope, and charity.’ ‘Clasped hands,’ not ‘Friendship’” begins article f of the appendix; while article h explains the imperative of detailing “costume, posture, and relationship to other devices” in tattooed representations of men and women—“e.g., ‘Woman clinging to a cross;’ ‘Man and woman embracing, houses, lighthouse and ship in the background;’ ‘Sailor standing by a tombstone, weeping willow overhead, cap in right hand, words IN MEMORY OF MY MOTHER on stone.”[6]

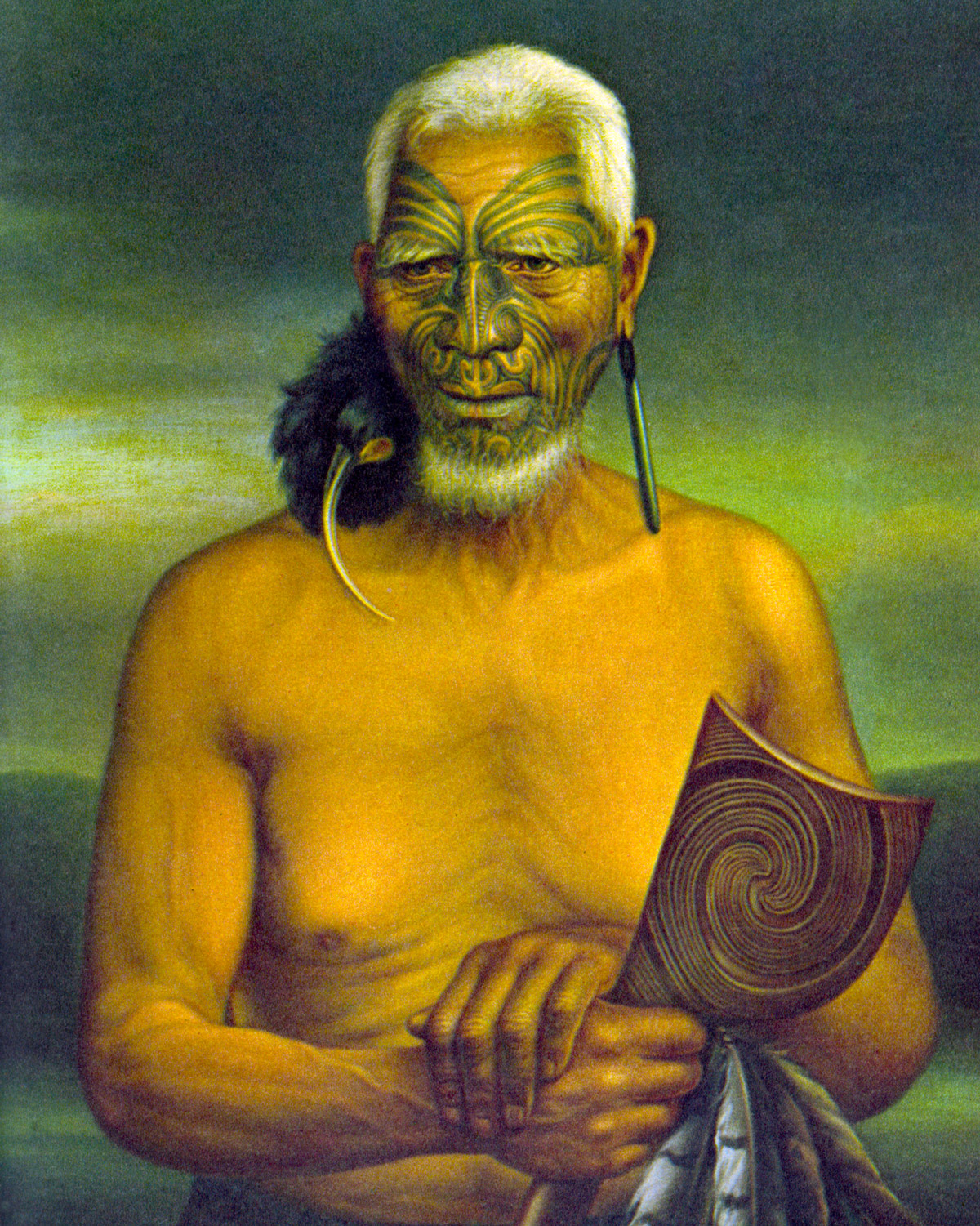

Along with the popularity of tattoos among seamen, after Cook’s second voyage—when he brought back to England two Polynesian islanders—tattooed indigenous people became fodder for public display, eventually finding their way into freak sideshows, dime museums, and other popular exhibitions. Some good Christians would go to world’s fairs specifically to study tattooed natives as preparation for embarking on faraway missions aimed at bringing the gospel to the heathens. Perhaps Tennyson’s renowned tattoo reverie echoed in their minds as they contemplated these spectacles:

The planets: then the monster, then the man;Tattooed or woaded, winter-clad in skins,

Raw from the prime, and crushing down his mate;

As yet we find in barbarous isles,—and here

Among the lowest.[7]

And so, from crude beginnings among worldly sailors and remote savages, over time more and more people started getting tattoos until today when blah blah blah. The End.

The only problem with this official version is that it omits the actual story of the introduction of tattoos to the west, abundant evidence suggesting that it long predates Cook’s voyage—and that it arose from the most sanctified, even sanctimonious, impulses of civilized society.

An Armenian known as “Prickly Jack” haunted hotels in the vicinity of the Holy Sepulcher, presenting certificates of endorsement from former clients to every traveler he could accost. One of these read: “This old fellow picked my arm until it was ‘deeply, darkly, beautifully blue,’ thereby giving me a deep and everlasting impression of Jerusalem.” Pairs of men hovered in the doorways of churches inquiring among passing pilgrims whether they would like to have the representation of a sacred object pricked into them. Young ladies pleaded with their fathers to approve their getting inked and suffered distress of mind as to where to place the mark so that it would neither stain the effect of a sleeveless décolleté costume, nor prove too inconveniently concealed to flash to a friend. When fathers objected, the maiden petitioner would counter, “Why, Mrs. So-and-So, and Lady So-and-So, and the Prince of Wales were tattooed.” It was the latter’s decision to have gotten a tattoo in Jerusalem during his visit in 1862 that gave punch to the appeal. As one observer noted, “By the time paterfamilias has a day or two of this, he usually gives in, and not only allows his fair teasers to follow the illustrious example of England’s future king, but like as not goes through the same operation himself.”[8]

The city’s tattoo shops, centered near the Holy Sepulcher, did the bulk of their business in the high pilgrimage season, and were only open in winter and spring. The workers were mostly Armenian and Syrian Christians, along with a smattering of gypsies and barbers of almost any faith.

The most common symbol was the Jerusalem Cross (one big crucifix with four tiny crosses set inside its right angles). The Star of Bethlehem—composed of a star, its rays, and three dots signifying the Holy Trinity—was also popular, though Christian visitors to Jerusalem could also choose to be inscribed with birds, fish, or fabulous animals. Muslims favored tattoos of names and sentences from the Koran, sometimes with a sword or anchor embellishing the inscription.

Documentation of the Jerusalem practice goes back at least to 1680, when a Lutheran theologian wrote that Christians from all over Europe making pilgrimages to the Holy Sepulcher would procure marks on their bodies “because of the special sacred awe associated with the place and because of the desire to prove that they had been there.”[9] Henry Maundrell’s famous 1697 account of traveling to Jerusalem includes a description of an idle Saturday morning that “gave many of the pilgrims leisure to have their arms mark’d with the usual ensigns of Jerusalem. The artists, who undertake the operation, do it in this manner. They have stamps in wood of any figure that you desire, which they first print off upon your arm with powder of charcoal: Then taking two very fine needles ty’d close together, and dipping them often, like a pen, in certain ink, compounded, as I was informed, of gunpowder and ox-gall, they make with them small punctures all along the lines of the figure which they have printed; and then washing the part in wine, conclude the work.”[10]

The legendary roots of the Jerusalem tattoo ritual lay in an incident in the life of King David. After David slept with Bathsheba, and dispensed with her husband Uriah by sending him to battle, he became seized with remorse. Anticipating Kafka’s In the Penal Colony, David arranged for the tale of his treachery to be pricked upon his arms and legs with a sharp iron stylus so that his crime would be constantly recalled to him. Even if not quite so ancient, the practice almost certainly began before the seventeenth century, and some believe that returning Crusaders were the first to import tattoos to Europe in a manner that became contagious.

Despite the archaic tie between tattooing and guilt, in Jerusalem’s latter-day tattoo vogue its associations were with spiritual invigoration. Tattoos were a device for bringing the spirit of the city back home in the body. A link was drawn between the act of tattooing and pilgrimage as such. The Armenian word for pilgrim is mahedesi—mah, “death”; desi, “I saw.” The term came to be applied to any tattoo mark created in Jerusalem, a mark of renewal by way of the tomb for western visitors, a token of their time spent in the holy city—a game with the reaper pricked out on the rippled canvas of the flesh. Yet if there’s such clear evidence for the existence of this rich, alternative history of the westward spread of tattoos, why has it been almost universally repressed? The solution to this mystery may lie neither with old sailors, nor South Sea Islanders, but with a new breed of biologists.

In 1863, Cesare Lombroso had the revelation that launched him on the path to becoming a criminologist. As a military physician bivouacked with a regiment in Calabria, he noted, “I beguiled my ample leisure with a series of studies on the Italian soldier. From the very beginning I was struck by a characteristic that distinguished the honest soldier from his vicious comrade: the extent to which the latter was tattooed and the indecency of the designs that covered his body.”[11] This realization inspired Lombroso to embark on what became probably the most extensive, and influential, study of tattoos yet undertaken. Indeed, Lombroso’s investigation into tattooed criminals remained a touchstone well into the twentieth century, when the seminal histories of tattoos were being written.

Using statistical tables that correlated numbers and types of tattoos with individual criminal histories, Lombroso revealed that that recidivist criminals were five times more likely to be tattooed than one-time offenders; he also noted that murderers and other violent criminals were almost twice as likely to be tattooed as forgers and swindlers. Arthur MacDonald, one of Lombroso’s followers, suggested that this resulted from the superior intelligence of the latter types of criminals, which enabled them “to see the disadvantage of tattooing.” The reasons Lombroso’s subjects had acquired their tattoos included “religion,” “the spirit of vengeance,” “laziness,” “vanity,” “feeling of association and of sect,” and “noble passions,” but the most prevalent were “atavism and erotic passions.”[12] Indeed, Lombroso proclaimed, tattoos represented “an atavistic compulsion.”[13] In a Popular Science Monthly article published in 1896, Lombroso chastised those women of London society who had adopted the fashion of tattooing their arms (probably with religious insignia): “The taste for this style is not a good indication of the refinement and delicacy of the English ladies,” he declared. “First, it indicates an inferior sensitiveness, for one has to be obtuse to pain to submit to this wholly savage operation … and it is contrary to progress.” Expanding on this idea, he concluded, “Nothing is more natural than to see a usage so widespread among savages and prehistoric peoples reappear in classes which, as the deep-sea bottoms retain the same temperature, have preserved the customs and superstitions … and who have, like them, violent passions, a blunted sensibility, a puerile vanity, long-standing habits of inaction, and very often nudity.”[14]

Lombroso and his disciples made the instinct to acquire a tattoo—even apart from the image—symptomatic of a regressive character. And they did so right at the time when the lineage of the tattoo was being charted by anthropologists and general historians. The hugely popular, centuries-old tradition of pilgrims to Jerusalem getting inked simply did not jibe with Lombroso’s notion of what tattoo-hunger signified. And this disjunction helped form a blind spot inherited by histories of tattoos down to the present day. What must have been, ever since Cook’s expedition, a tricky coexistence between tattoo typologies became unsustainable with the specter of atavism.

At least in theory. For, notwithstanding the narrative gap, the habit itself continued to prove irresistible—thriving in Jerusalem throughout most of the twentieth century. And one family remains as testimony to the continuity of the Jerusalem tattoo trade through all the changes in western attitudes toward tattooing.

Two hundred years later, an English scholar visiting Jerusalem happened upon the shop of a coffin maker and tattooer by the name of Jacob Razzouk who had a collection of 168 wooden blocks carved in heavy relief featuring unique designs. Most but not all of the patterns were Coptic, and on investigating further, one block was found dating back to 1749. Jacob proved to be a descendent of Jersius. The Razzouk family had been passing down their art in a continuous line ever since their arrival in Jerusalem. Jacob himself had introduced the first electric tattoo needle to Jerusalem, powered by a car battery. Long lines of people would unspool from the door of his shop, singing and dancing. British troops and Haile Selassie were among his clients. People hovered over Jacob ululating while he worked. He was kept so busy, his son Anton later recounted, that he didn’t eat.

Anton and his sister Georgette were trained by their father using slabs of meat on which they practiced how to pull the skin just tight enough and how deep to insert the needle. Their dyes were concocted from a secret recipe of oil-lamp soot and high-quality red wine that made the tattoos bright. They built their own electric needle from two metal doorbells.

By the time Anton began reminiscing about the heyday of his father’s career, he himself was in his late fifties. Several articles published about the Razzouks around 2002 are bitterly elegiac. Even though Anton defended the proverbial belief that tattoos were the “key to heaven”—declaring “If I have a cross or a picture of Jesus on my hand and I am about to reach out and steal, I see it, and it reminds me not to”—the key was getting awfully rusty.[15]

Whereas his father would tattoo as many as five thousand pilgrims in two weeks, Anton claimed, he himself was lucky to get two hundred in a year. Crosses and virgins had been replaced by butterflies and roses. He complained about the young people worried over AIDS who objected when he told them that he would often reuse the same needle a hundred times. “Changing the needle takes time, and they will not accept it when I tell them the alcohol I use and the dyes are enough,” Anton lamented.[16] To top off his woes, his son didn’t like the sight of blood. The Razzouk tattooing dynasty, active in Jerusalem for 250 years, seemed to have reached an end.

But the Lord of Tattoos works in mysterious and surprisingly good-humored ways. Lo and behold, in 2010, the Facebook page of Wassim Razzouk—Jacob’s grandson—went live. In his profile photo, Wassim stands before a black sports car in a leather jacket, jeans, red shirt, and sunglasses, looking like a somewhat more relaxed version of Sylvester Stallone. He studied hotel management and has worked at the Foundation for Law and Government. But Wassim has taken up the needle again with a passion. His profile touts his family’s lineage in the business with pride and concludes, “My father has been teaching me as his father has taught him, and I have decided to carry over the tradition and the heritage and hopefully, one day, teach it to my sons.”

The 188 online photos of Wassim’s most recent creations are a dizzying ecumenical delight. The first is a psychedelic snail wearing a keffiyeh, the second is the Hebrew word for “enjoy” inscribed on someone’s palm. There are crosses and dragonflies, musical notes, portraits of Che and Arafat, phrases in Arabic beneath olive trees, lines in Hebrew, Roman numerals, and heavy-metal goblins framed by battle axes.

Darwin, musing in the Descent of Man on the intense similarity between men of all races in “tastes, dispositions and habits,” remarked that this similarity was shown “by the pleasure which they all take in dancing, rude music, acting, painting, tattooing, and otherwise decorating themselves; in their mutual comprehension of gesture language, by the same expression in their features, and by the same inarticulate cries, when excited by the same emotions.”[17]

Ultimately, perhaps, the universality of this drive to scramble the given pattern of our flesh might conjure another kind of avatar than the one Lombroso spooked us with. More, even, than a practice of self-expression, we could look on these lines the hue of blood still in the veins as clues to some half-forgotten scene of common yearning—mnemonics of the hour before the cut of race, the carve of caste, and the prick of ideology left their own marks on us.

It’s true that tattoos have also been inscribed precisely to establish tribal and gang affiliations. However, this form of branding is but a phase in the tattoo’s own evolution. Like the butterflies and oriental insignia that so many contemporaries engraved into their ankles and biceps at some impulsive hour—now aging into little uniform blue clouds—the designs of even the most sectarian tattoos tend in the fullness of time to smear and blur. Born of a universal urge, the tattoo mark itself aspires to universality.

- Archibald Ross Colquhoun, Amongst the Shans (New York: Scribner & Welford, 1885), pp. 208, 211.

- American Anthropologist, vol. 10 (1908), p. 687.

- Herodian, History of the Empire: Books 1–4, Book III, chapter 14, sections 6–8, trans. C. R. Whittaker (Cambridge, Mass.: Loeb Classical Library, 1969), pp. 359–361.

- Joseph Banks, Journal of the Right Hon. Sir Joseph Banks, ed. Sir Joseph D. Hooker (New York: Macmillan, 1896), pp. 128–129.

- Herman Melville, Redburn, White-Jacket, Moby-Dick (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., 1983), p. 525.

- Manual of the Medical Department, United States Navy (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906), p. 62.

- Alfred Tennyson, The Princess (Boston: The Athenaeum Press, 1897), p. 105.

- Albert Rhodes, Jerusalem As It Is (London: John Maxwell and Company, 1865), p. 424.

- Quoted in Celean Jacobson, “Long Tradition of Pilgrim Tattoos a Dying Art in Jerusalem,” Southeast Missourian, 8 August 2002, available at semissourian.com/story/84306.html. Accessed 18 June 2012.

- Henry Maundrell, A Journey from Aleppo to Jerusalem, at Easter, A.D. 1697 (London: J. White and Co. and J. Nunn, 1810), p. 100. Spelling modified.

- Quoted in Jane Caplan, “‘One of the Strangest Relics of a Former State’: Tattoos and the Discourses of Criminality in Europe, 1880–1920,” in Criminals and their Scientists: The History of Criminology in International Perspective, eds. Peter Becker and Richard F. Wetzell (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), p. 337.

- Arthur MacDonald, Statistics of Crime, Suicide, Insanity, and other Forms of Abnormality (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1903), p. 66.

- Lombroso quoted in Jane Caplan, op. cit., p. 346.

- Cesare Lombroso, “The Savage Origin of Tattooing,” The Popular Science Monthly, vol. 48 (1896), pp. 793–803.

- See, for example, Danielle Haas, “‘Key to Heaven’ Fades from Body and Memory,” The San Francisco Chronicle, 29 November 2002; Celean Jacobson, “Long Tradition of Pilgrim Tattoos a Dying Art in Jerusalem,” op. cit.; and Wassim A. Razzouk, “Razzouk Tattoo Art Heritage,” available at facebook.com/notes/wassim-a-razzouk/razzouk-tattoo-art-heritage/124321697602327?ref=nf. Accessed 5 June 2010.

- Danielle Haas, “‘Key to Heaven’ Fades from Body and Memory,” op. cit.

- Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1876), p. 178.

George Prochnik is a New York–based writer. His most recent book is In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise (Doubleday, 2010). He is currently writing a book on Stefan Zweig and exile that will be published by Other Press.