Professor Naess’s Alpine Garden

A conversation with the pioneer of deep ecology

David Rothenberg

Arne Naess, 90 years old, may very well be the last surviving member of the Vienna Circle, that erstwhile group of grave philosophers who set the previous century on the steel road to logic and reason. Naess is the only one left to poke his nose into the twenty-first century. Back in 1930, sent to Vienna to become a concert pianist but soon stuck at the roundtable with analytic thinkers like Carnap and Quine, the 18-year-old Norwegian pipsqueak raised his hand to complain, “I think you are spending too much time quoting Wittgenstein. Why can’t I be quoted a bit more?” He has been causing trouble like this his whole life.

A few years later, while his analytic buddies were talking on and on about a philosophy based on “common sense,” without metaphysical flights of fantasy and other forms of continental mush, Naess wrote up a questionnaire and passed it out on the street. There was only one question: “How do you decide what is true?” If there really was such a thing as a common sense notion of truth, everyone would presumably give a similar answer. However, the respondents all gave a range of answers, similar to the various positions held by philosophers throughout history. So much for that theory. What did the other theorists expect? They never thought of going out to ask people what they thought.

Naess has spent a lifetime in many areas of the philosophic enterprise, from working in the wartime Resistance against the Nazis to defining democracy for UNESCO to systematizing the principles of Gandhian nonviolence as a coherent philosophy. What he is best known for today, however, is for coining the phrase “deep ecology” to describe a brand of environmentalism that espouses that we must fundamentally change our ideas about how humanity fits into the natural world before we can dig our way out of the environmental crisis that befalls humankind and the planet. We need to cultivate an identification with the natural world, where all living things have an equal right to live and flourish. We need a sense of human humility, where we never disturb too much. Will we succeed? “I am optimistic,” Naess now muses after a lifetime of trying, “but for the 22nd century, not for this one.”

Deep ecology has often been taken as the guiding philosophy of the worldwide wilderness movement, which believes that pure, wild nature, far from human influence, is the most important part of the planet to preserve. Advocates of this view are often criticized by another kind of ecologist, one that cares most about tending the Earth like a garden, sticking close to our backyards, tilling and shaping the land rather than sealing it off like a pristine temple. These gardening environmentalists sometimes find Naess to be too extreme, unrealistic, and misguided by sequestering nature from the reality of human culture.

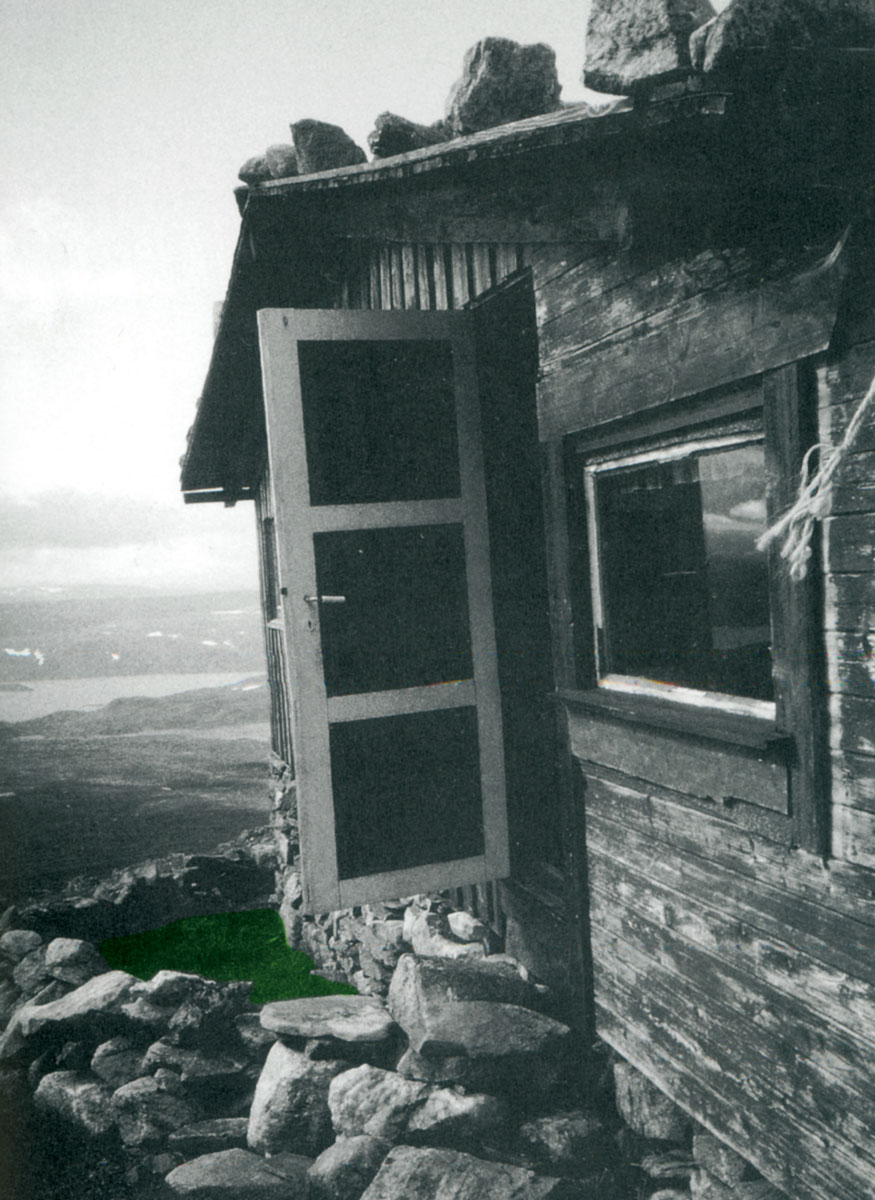

Now Naess responds by pointing out that there is no schism between those who want to save the garden and those who love wild places. His favorite place in the world is at his mountain hut far above the timberline beneath the whale-shaped Hallingskarvet mountain in central Norway. The hut is a three-hour walk uphill through the tundra from the train station at Ustaoset. He built it in 1936, and it still feels “six thousand feet above men and time,” as Nietszche once said. The cabin is called “Tvergastein,” which means “crossing the stones.”

Inside the cabin is an intellectual world brightened by humor and curiosity. The library, inside a room the size of a large closet, is impressive—the complete works of Aristotle and Plato; handbooks of chemistry and physics; novels of Dostoyevsky; teach-yourself manuals for Rumanian, Icelandic, and Chinese; the most extensive Sanskrit-English dictionaries available; Buddhist logic; Marxist rhetoric. It once housed the complete edition of Auguste Comte in French, until it was burned for fuel on a particularly cold winter night. There are generations of rock climbing equipment, from heavy leather boots and steel pitons to light carabiners and high-tech nylon shoes. There are personal contraptions only the master understands: kerosene lamps that heat tea and soup at the same time, solar-powered reading lights that work even if the sun doesn’t shine for weeks.

And just outside the door is a tiny grassy space, ringed with a small stone wall. “Watch out,” Naess warns all visitors. “Don’t step there, stay on the rocks. That’s my garden.” Here is how Naess described life in this garden in a series of interviews I did with him in 1992.[1]

Arne Naess: If a flower in a botany text is described as being from ten to thirty centimeters tall, you might find the same flower here at Tvergastein, elevation six thousand feet, and it’s only five centimeters tall, or even less. But the flower is complete. In a dry summertime like this one you have this Arctic gentian and it’s only one centimeter high, but still a fantastic flower.... I have sat here in the eight-meter square garden and just tried to count all the thousands of plants that blossom there. The task is endless, and there is no need to wish to finish it.

David Rothenberg: A microcosm of the country.

A microcosmos, and it is fantastic to see the changes. I have learned an admiration for the minute, to say very simply: Where others see adversity, a harsh and tough climate, I see the Self-realization of tiny beings in nature.

How did this move over into a philosophical focus on ecology and environmental problems?

That should be quite clear. There is a kind of equal status of organisms at extremely different levels of development. You get to appreciate this one small ecosystem, and you see yourself as part of this ecosystem. I found a kind of rational basis for this feeling of belonging to this rich world of animals and plants and rocks. Humans do not depend on nature by minding it, trying to dominate more and more and be less dependent; you see the dependence as a plus, because it means an interrelation, whereby you yourself get to be tremendously greater, reaching from macroworld to microworld and back again. Feeling extremely small in the dimensions of the cosmos, you yourself get somehow widened and deeper, and you accept with joy this thing that others might perceive as a duty: to take care of the planet....

But concern for nature does not preclude concern for people.

Get rid of that dualism! The term ‘environmentalism’ is meaningless because it implies a very artificial kind of cleavage between humans and everything else. From our individual selves we look out toward the Self of the world.

How does one care best for a tiny garden of miniscule plants and grasses peaking through sheltered spaces between stones? Easy. Just be sure to piss in the right direction as you kick open the door on a bright summer night and hope that the wind is with you.

- David Rothenberg, Is It Painful to Think? Conversations with Arne Naess (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992), pp. 64-66.

David Rothenberg spent several years in the 1980s working closely with Arne Naess in Norway. His latest books are Blue Cliff Record: Zen Echoes and Sudden Music: Improvisation, Sound, Nature. The latter includes a CD of his music. He is professor of philosophy at the New Jersey Institute of Technology.