The Cinematic Spasm

Lights, camera, achoo!

Aaron Schuster

Rub your hands thrice across your foreheads—blow your noses—cleanse your emunctories—sneeze, my good people!

—Laurence Sterne, Tristram Shandy

Hitchcock was essentially a comic filmmaker. During a 1967 interview, when asked by an audience member why he’d never made a comedy, the director countered, “But every film I make is a comedy.”[2] Along these lines, I believe it is one of Hitchcock’s minor films that provides the key to his oeuvre. The Trouble with Harry, a film about the upheavals caused in a tranquil rural community by the appearance of an inconvenient corpse, exemplifies two of the defining elements of Hitchcock’s cinematic technique: the art of dialectical reversal—the bucolic countryside as the setting for a murder mystery or, in other films, Hitchcock’s penchant for cold blondes who signify fiery sexual passion—and the eminently English capacity for understatement, as when the lady who stops a man dragging a corpse ask matter-of-factly, “What seems to be the trouble?” Even Vertigo, a cinematic version of Freud’s “Mourning and Melancholia” if there ever was one, contains plenty of humorous touches. Think of the droll exchange near the beginning about a brassiere designed by an “aircraft engineer” on the principle of the cantilever bridge—no doubt a reference to the amply bosomed Kim Novak, who replaced the more modestly chested Vera Miles, Hitchcock’s first pick for the role of Madeleine/Judy.[3]

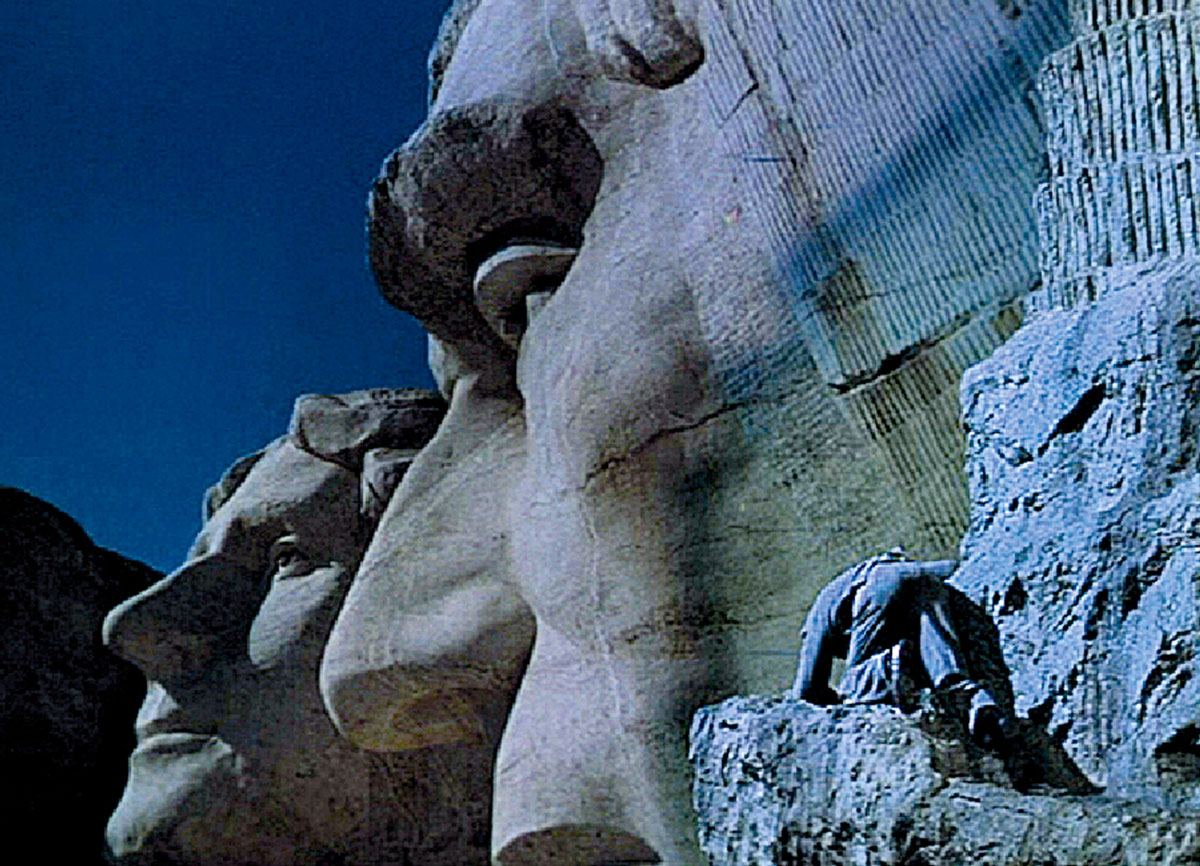

Did the master of suspense have a favorite comic scene? In the same interview we read: “I think one of the funniest films I have ever seen is Laurel and Hardy in a film called Bonnie Scotland. The longest take I have ever seen on the screen comes when the two of them are standing on a Scottish bridge and Laurel is taking snuff. And he sneezes right into the snuff box. And all the snuff goes into Hardy’s face. It was then the longest take I have ever seen before anything happens. And finally, this long sneeze comes. The sneeze is so big that he tilts backwards into the river below. Laurel is left on the bridge and nothing came up but water and fish every few seconds.” Perhaps it was this delightful slapstick sequence, with its impeccable timing and exaggerated gestures—Laurel, still on the bridge, is drenched by water launched by Hardy’s vigorous sneezes (indeed, at one moment the camera itself is drawn into the whirlpool)—that set Hitchcock’s comic imagination into motion. Lehman wanted to write the “Hitchcock picture to end all Hitchcock pictures.” What would it mean to film the ultimate sneeze?

The philosophy of the sneeze can be said to have begun with Aristotle, who in the History of Animals wrote that “sneezing is the only sort of breath that has divinatory significance and is supernatural.”[6] In the section of Problems concerned with the nostrils, the philosopher analyzed questions such as: Why does sneezing stop hiccups? (The violence of the sneeze breaks up the trapped air which causes hiccups); Why does looking at the sun provoke sneezing? (Aristotle attributes what we now call the “photic sneeze reflex”[7] to the heat of the sun evaporating bodily moisture, producing an excess of breath which is then expelled through the nose); Why is sneezing considered divine, but not farting and burping? (The head is the most sacred part of the body); and, Why does man sneeze more than any other animal? (Human beings have a unique combination of wide breath channels and small, short nostrils).

In contrast to this classic systematic approach, Aristotle’s teacher presented the sneeze in a much more playful fashion, as a figure of humor and romance in a dramatic scene. Plato’s Symposium, one of the great texts on love in the Western tradition, is also the site of one of its most profound sneezes, occurring at a crucial turning point in the dialogue.[8] During the speech of Pausanias, Aristophanes suffers from a fit of hiccups, forcing a rearrangement of the order of the speakers (the pure slapstick aspect of the Symposium is highly underappreciated—one has to imagine Pausanias lecturing the half-inebriated party guests about Athenian law on pederasty with Aristophanes all the while hiccupping in the background). Eryximachus, a medical doctor (whose name means hiccup- or belch-fighter), takes Aristophanes’ place after counseling the comedic playwright on various hiccup cures—hold your breath, gargle with some water, or else tickle your nose with something and sneeze. At the end of his discourse, in which love is portrayed as harmony and proper order, the good doctor observes that Aristophanes’ hiccups have finally stopped. “Indeed,” Aristophanes remarks, “[the hiccupping] did cease, yet not before in fact the sneeze was administered to it, so as to cause me to wonder that the orderly part of the body desires the sort of noises and ticklings of which the sneeze itself consists. For [the hiccupping] ceased just as soon as I administered the sneeze to [the orderly part].”[9] Before launching into his tragic theory of love as the search for the missing half, the hiccuping-sneezing episode allows Aristophanes to open with a quick satire of Eryximachus’s medical wisdom: as the sneeze cure would seem to demonstrate, the restoration of order in the body is ironically produced through the combination of two disorders. What else might Plato be telling us if not that, in the case of Eros, only one spasm can “cure” another?

Duchamp’s assisted readymade, Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy? (1921), consisting of blocks of marble shaped like sugar cubes, a thermometer, and a cuttlebone shut inside a birdcage, all painted white, is one of the stranger of his constructions, doing for sneezes what his jagged cubist painting did for staircase-descending nudes. “Of course the title seems weird to you,” Duchamp remarked, “since there’s really no connection between the sugar cubes and a sneeze. First of all there’s the dissociational gap between the idea of sneezing and the idea of Why not sneeze? because after all, you don’t sneeze at will; you usually sneeze in spite of your will. So, the answer to the question, Why not sneeze? is simply that you can’t sneeze at will!”[10] If the first part of the title plays on the involuntary nature of the sneeze,[11] the second conjures its erotic quality: Rose Sélavy is a wordplay on Eros c’est la vie, “Eros is life,” and the pseudonym adopted by Duchamp in the 1920s, which he later spelled Rrose to underline the pun. If Rose/Eros does not sneeze, it is perhaps because, true to her nature as the child of Lack and Craftiness, the final satisfying release is left in abeyance.[12]

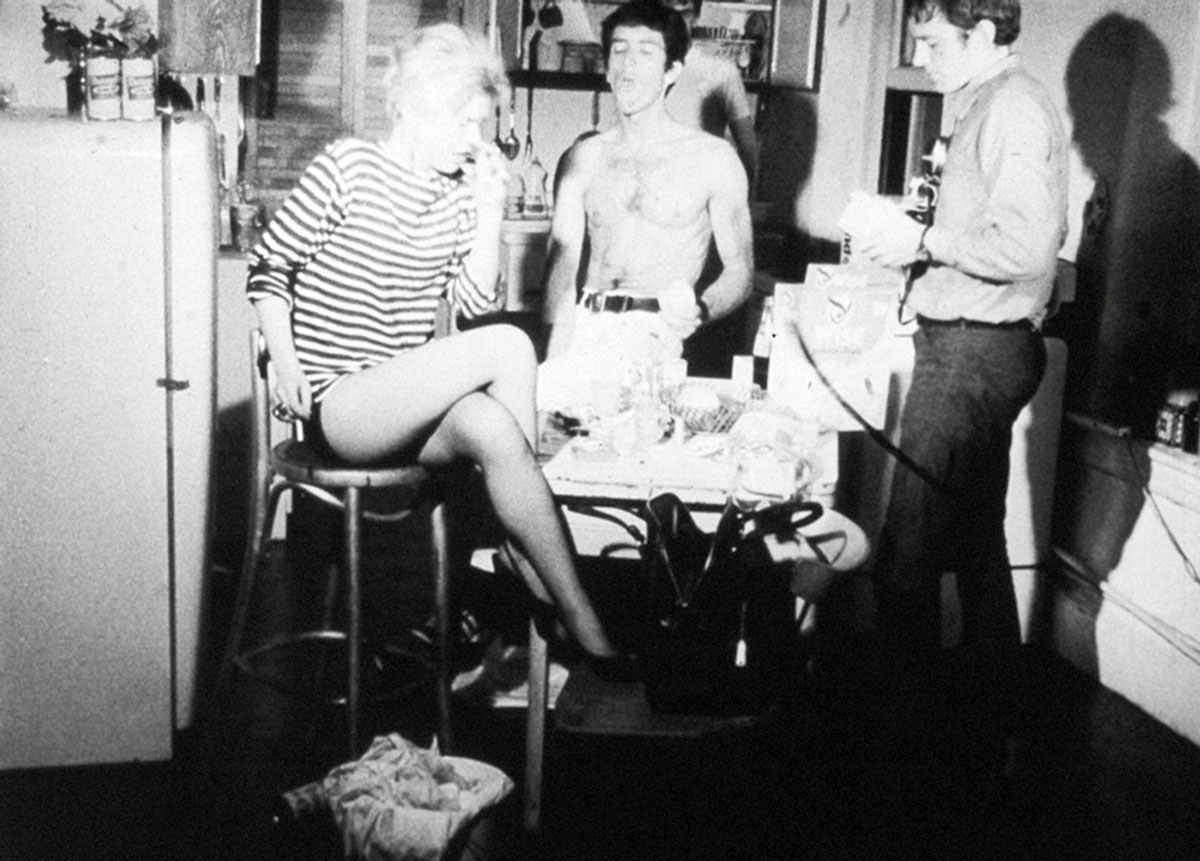

But there’s more: “And then there’s the literary side if I may call it that, but ‘literary’ is such a stupid word, it doesn’t mean anything … but at any rate there’s the marble with its coldness, and this meant that you can even say you’re cold, because of the marble, and all of the associations are permissible.”[13] Like perhaps catching a cold (if I may be allowed this association, which does not, however, work in the original French)? This brings us to Warhol’s Kitchen (1965), a film meant as a vehicle for Factory superstar Edie Sedgwick, and scripted by Theater of the Ridiculous inventor and key Warhol collaborator Ronald Tavel. Kitchen is one of the artist’s lesser-known films, and it is still difficult to see a copy today; a year later, Tavel and Warhol would make the more renowned Chelsea Girls. Despite its obscurity, Kitchen is noteworthy for its aimless witty dialogue and its claustrophobic atmosphere. Norman Mailer enthused that “one hundred years from now they will look at Kitchen and see the essence of every boring, dead day one’s ever had in a city and say, ‘Yes, that is the way it was in the late Fifties, early Sixties in America. That’s why they had the war in Vietnam. … That’s why the horror came down.’ Kitchen shows that better than any other work of that time.”

Like Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?, the movie takes place entirely in its own cramped little “cage”: sound- and cameraman Buddy Wirtschafter’s wholly white SoHo loft kitchen. The “mollusk-memoried” actress (in the words of Tavel) had trouble learning her lines, so parts of the script were hidden strategically throughout the set, and the starlet was told to sneeze whenever she didn’t know the text. This made Sedgwick seem like she had a cold, and her many sneezes ended up providing the film with an unexpected comic dimension, punctuating the half-improvised, disjointed conversations bathed in blasé sexuality and downtown disaffection. Between the suspended sneeze of Rose Sélavy and the flurry of them let loose by the sniffling “It girl” lies the sneeze as object of modern conceptual cool.

The exaggerated explosiveness of the sneeze was also exploited for comic effect by the Marx Brothers. In fact, Harpo’s only onscreen “line,” occurring in At The Circus (1939), is a thunderous “Achoo!” which sends the furniture flying across a cramped little room. But That Fatal Sneeze goes one giant sternutation further. At the very end of the film, the poor man literally sneezes himself into oblivion, exploding in a cloud of white smoke—an optical illusion created by stopping the camera and replacing the actor with a small smoke pot. This scene may be viewed as staging a fundamental nasal fantasy: the supreme sneeze is a lethal one. And indeed, there is a long history connecting sneezing with death.

In the Middle Ages, the Bubonic Plague lent an aura of evil to the sneeze; Pope Pelagius II allegedly perished from the disease while sneezing. During the same period, the common practice of blessing a person after sneezing gained a new urgency; Pope Gregory VII enjoined his followers to say “May God bless you” as an equivalent to “I hope you may rid yourself of the bacillus.”[14] The Greeks considered sneezes to be miraculous signs; in the Odyssey, Penelope interprets her son’s sneeze as a divine confirmation of her death wish against her suitors. Sneezes without prophetic relevance, on the other hand, were viewed as a disturbance of the gaseous or windy life-soul—the Greek word for soul is etymologically related to the word for blowing—and following a sneeze it was customary to say, “Zeus, save me.”[15] The Romans similarly saw sneezing as a potentially dangerous departure of life-spirit from the head, the passing away of what they called genius. In the Jewish tradition, there is an old belief that before the time of Jacob, the first man to perish from illness, sneezing was instantly fatal: a strong nasal blast expelled the life force from the body, reversing the movement of divine animation recounted in Genesis 2:7, “God blew into Adam’s nostrils the soul of life.” Such was the “surprising” nature of human mortality in ancient times: no sickness, no debility, no warning signs of any kind, just one sneeze and you’re done for.

Cinematic interest in this highly charged reflex may be traced back to the very dawn of filmmaking. One of the first copyrighted motion pictures, inspired by Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic studies of motion, was in fact a study of a sneeze. Made by W. K. L. Dickson at the Edison Laboratory and composed of eighty-one frames, this filmic “primal scene” features Fred Ott, an Edison employee who had a penchant for practical jokes. The film, titled Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze, or simply Fred Ott’s Sneeze, developed a kind of mythical status, in part due to Ott’s tireless self-promotion as the world’s “first” movie star, with the sneeze footage put forward as the world’s “first” movie. Like all origin stories, this one is mired in exaggerations and half-truths, which were eventually debunked by film historian Gordon Hendricks in a short article published in Adolfas and Jonas Mekas’s avant-garde journal Film Culture. As Hendricks explains, the movie began as the brainchild of Barnet Phillips, a contributor to Harper’s Weekly who proposed to Thomas Edison to write an article about the new peephole kinetoscope for which the journalist wanted the recording of a sneeze. The publicity-savvy Edison replied that he would be happy to furnish the requested footage. Two months later, after additional prompting by Phillips, Edison asked his assistant Dickson to shoot Sneeze. The film was copyrighted on 9 January 1894, not quite the first of its kind, as Dickson had already copyrighted several other short subjects in the previous months. Phillips’s article, “Record of a Sneeze,” appeared in Harper’s Weekly on 24 March, accompanied by a reproduction of the entire footage. An excerpt of the article reads: “The Edison kinetoscope gives the entire record of a sneeze from the first taking of a pinch of snuff to the recovery. As seen in this wonderful mechanical device of Mr. Edison's invention, when he exhibits the series of photographs the figure actually sneezes, and the phonograph as an accompanist sounds the precise ‘as–shew’. The illusion is so perfect that you involuntarily say, ‘Bless you!’” One crucial detail: in the original proposal for the film, the sneezer was meant to be not the ruddy mustachioed Ott but “some nice-looking young person,” “a woman.” To paraphrase Godard: all you need to make a movie is a girl and a pinch of snuff.

In reference to Fred Ott’s Sneeze, Mary Ann Doane writes that “contortions of the body and especially its involuntary and violent movement were perceived as particularly cinematic.”[16] It is the unique capacity of cinema to capture and break down movement, to reveal the secrets of normally imperceptible transitions and variations, that makes the sneeze such an attractive filmic subject. In his article, Phillips analyzed the roughly two-second gesture (“this curious gamut of a grimace”) into ten constituent stages, each one identified with a corresponding frame: priming, nascent sensation, first distortion, expectancy, premeditation, preparation, beatitude, oblivion, explosion, and recovery. This remarkable phenomenology—practically indistinguishable from a description of religious or sexual ecstasy—again highlights the erotic character of the sneeze, and in her study of pornography, Linda Williams claims that the film ought to be situated between “the prehistoric scientific motion studies of Muybridge and the sensationalist later spectacles that were to mark the more advanced stages of primitive cinema and the primitive hard core.”[17]In effect, Edison’s film is a rudimentary “money shot” that may be seen as part of the then-emerging scientia sexualis which aimed at revealing the secrets of bodily pleasure—especially female pleasure—through the use of photography and clinical observation.

A final cinematic reference makes this link between sneezing and feminine jouissance explicit in a totally ridiculous way: in a scene from the Steve Martin romantic comedy The Lonely Guy (1984), Larry (played by Martin) finally beds his love interest Iris, who confides that she has never had a “you know what.” Larry’s initial amorous advances produce no effect, until an inadvertent sneeze sends an ecstatic shudder through Iris’s body. Capitalizing on this discovery, the hapless lover performs a series of sneezes in order to induce pleasure in the woman, thereby reversing the standard cultural obsession about female simulation. In this case, man has fake sneezes, woman has real orgasms.

- Alfred Hitchcock and François Truffaut, Hitchcock/Truffaut (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983), p. 102.

- Alfred Hitchcock, interviewed by Bryan Forbes, the National Film Theatre,1967, available at www.bfi.org.uk/features/interviews/hitchcock.html [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 26 November 2010.

- It was during the filming of The Outlaw in 1941 that famed aviator Howard Hughes, putting his knowledge of aeronautical engineering to good use, invented the underwire push-up bra for his star Jane Russell. Russell’s emphasized décolletage resulted in The Outlaw being kept out of cinemas for three years by Hollywood’s Production Code Administration.

- I refer to Wilson D. Wallis’s wonderfully titled study “The Romance and the Tragedy of Sneezing,” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 9, no. 6 (December 1919).

- There are also significant literary treatments of the sneeze. In Anton Chekhov’s short story “The Death of a Government Clerk,” a low-level bureaucrat accidentally sneezes on the back of the neck of a civilian transport general one night at the opera. He spends the rest of the story trying to apologize for involuntarily spattering the general, but his many attempts to excuse himself are coldly rebuffed; the injured party prefers not to even acknowledge the occurrence of the unfortunate episode. In the end, the hero, exhausted and unforgiven, lies down on his couch and expires, as if (to paraphrase the closing line from Kafka’s The Trial) the shame of the sneeze will eternally outlive him.

- Aristotle, Historia Animalium, trans. A.L. Peck (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 1965), 1.11.492b.

- Otherwise known as the ACHOO (autosomal dominant compelling helio-ophthalmic outburst) syndrome.

- Incidentally, Plutarch reports a theory that considered Socrates’ daimon to be only a sneeze. See Arthur Stanley Pease, “The Omen of Sneezing,” Classical Philology, vol. 6, no. 4 (Oct 1911), p. 430.

- Plato, Symposium, trans. W. R. M. Lamb (Cambridge: Loeb Classical Library, 1925), 189a. At one point during his commentary on the Symposium in his seminar on “Transference” (1960–1961), Jacques Lacan reports Alexandre Kojève telling him that he will never understand the Symposium until he can explain why Aristophanes gets the hiccups. He should have added: and sneezes.

- Jean-Marie Drot, “Jeu d’Échecs avec Marcel Duchamp,” unpublished interview for the soundtrack of a film made by ORTF television, 1963. Quoted in Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Delano Greenidge, 1997), p. 487.

- As a counterpoint, consider the case of comedian Billy Gilbert, famous for his sneeze routines, who worked with Laurel and Hardy in the 1930s and provided the voice for Sneezy in the Disney production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: Gilbert was famous for his remarkable ability to sneeze on cue. This seemingly miraculous mastery over the involuntary recalls the story of Guy de Maupassant, who, among his many talents, was reportedly able to make his member rise at will.

- As Jerrold Seigel writes, “R[r]ose prefers the state of permanent anticipation that is not sneezing to the release of tension the small explosion would bring: because eros is desire, delay is the only state in which it survives undiminished.” The Private Worlds of Marcel Duchamp: Desire, Liberation, and the Self in Modern Culture (Berkeley: University of California, 1995), p. 171. In the Symposium, Plato recounts the myth of Eros’s birth from the union of Poros (Craftiness or Resourcefulness) and Penia (Lack).

- Arturo Schwarz, op. cit., p. 487.

- See J . J. M. Askenasy, “The History of Sneezing,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, vol. 66 (1990), p. 549.

- I draw here, and in what follows, on Richard Broxton Onians, The Origins of European Thought: About the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time, and Fate (Cambridge: Cambridge University, 1951), pp. 103–105, 132, and passim.

- Mary Ann Doane, The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, The Archive (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, 2002), p. 177.

- Linda Williams, Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the “Frenzy of the Visible” (Berkeley: University of California, 1989), p. 52. See also Marjorie Garber, Symptoms of Culture (London: Penguin, 1998), pp. 221–225.

Aaron Schuster is a writer based in Berlin, where he is a fellow at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry. He completed a PhD in philosophy at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, in 2010.