IPA Review, March 2008, p. 49, www.ipa.org.au

To download this article as a PDF (160 KB), click here

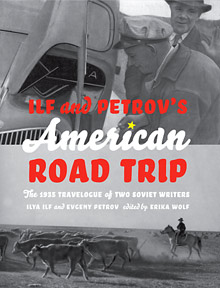

Ilf and Petrov’s Excellent Adventure by Chris Berg

In 1931, some 10,000 American tourists travelled to the Soviet Union in order to see what the great Soviet Experiment could offer their depression ravaged country.

But the tourist traffic heading the other direction was much lighter. Ilf and Petrov’s American Road Trip is the travelogue of two Soviet satirists, Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov, as they crossed the United States, scribbling reports for Pravda readers back home. Like the American fellow-travellers who were merrily shuttled from Potemkin village to Potemkin village, the report of their journey reveals more about their home country and culture than the country they ostensibly went to investigate.

The resulting photoessay, which was originally published in the Russian magazine Ogonek, (roughly equivalent to Life) reproduced the snapshots taken by Ilya Ilf on their journey with their satirical impressions of their trip. American Road Trip is a delightfully naïve interpretation of American society in the depression era.

In this book edited by Erika Wolf, a historian of Soviet art, Ilf’s photographs are affectionately reproduced for the first time in an English language publication.

Ilf’s photographs are more happy-snaps than Ansell Adams. Many photos appear to have been taken by sticking the camera out of the windows of their car. The book is full of slightly askew pictures of things the two Russians found interesting, or at least notable—some ‘handsome and unusually elaborate’ species of cactus, the childhood home of Mark Twain, an advertisement for whiskey that incorporated a statue of a horse, and a sign that notified visitors they were entering the little town of Moscow, Ohio.

There are some photographs of more political importance. A swaying sign in the street with the lettering ‘REVOLUTION IS A FORM OF GOVERNMENT ABROAD’ is, to Ilf and Petrov, bourgeois intimidation of the working class. (As Erika Wolf notes, the joke was on the Russians—the sign was instead an advertisement for a popular humour anthology illustrated by Dr Seuss. Ilf and Petrov were the foremost satirists of the Soviet Union, but they were unable to recognise the work of their American colleagues.)

For the most part, Ilf’s camera is non-political. Indeed, American Road Trip generally avoids direct political criticism. Ilf and Petrov are obviously fond of the country they are studying. They are fascinated by the advertising they see plastered across their trip, and direct much of their satirical energy towards Coca-Cola and cigarette advertising:

The fiery writing burns all night long above America and all day long the garish billboards hurt your eyes: ‘The Best in the World! Toasted Cigarettes! They Bring You Success! The Best in the Solar System!’

When we read how foreign the most basic and innocuous advertising seems to the two Russians—they are surprised that that towns advertise themselves on billboards beside the highway—we don’t gain a better picture of the United States in the 1930s, but of the Soviet Union.

They are highly sympathetic to the Native Americans living on reservations, predictably seeing them as remnants of a social structure in opposition to the dynamic capitalism of the east and west coasts. (Although as Erika Wolf notes, Ilf and Petrov are once again tricked, as a Native American who pretends to be unaware of civilisation was actually a famous photographer and clown dancer on tour.) Similarly, a trip through North Carolina confirms their Soviet views about American race relations—deep in the Jim Crow era, it is fair to say they had a point.

What does surprise the modern reader is the unfocused rage they direct towards American filmmaking. ‘We watched at least a hundred picture shows and were simply depressed by the amount of vulgarity, stupidity and lies’. Certainly, it would be hard to defend the vast piles of films which were produced to fulfil contractual obligations in the studio system during Hollywood’s Golden Age, but cheaply written and produced movies are hardly a unique feature of American cinema. The cookie-cutter productions of Soviet cinema during the ideologically rigid Stalin era are, on average, of a far lower quality than comparable American films, and have certainly held up worse over time. Ilf and Petrov may have been outraged more by the ideological content of Hollywood films than their quality.

American Road Trip is certainly at the margins of Soviet culture in the 1930s, but it is more than a historical curiosity. Satire was a major part of Russian culture before and after the October Revolution. The lives of Illya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov illustrate how mixed the bureaucratic approach to political satire could be. Their 1928 novel The Twelve Chairs flirts with political criticism, but they remained in favour—other well-known satirists, such as those in OBERIU literary collective, were killed in Stalin’s purges for sedition.

Ilf and Petrov do little more than reflect dominant Soviet thinking about their ideological opponent, but they are never heavy handed or propagandistic. American Road Trip purports to be a study of the United States, but instead fascinatingly reveals the strength of Soviet ideology and the Russian mindset.