Öyvind Fahlström’s Aviary

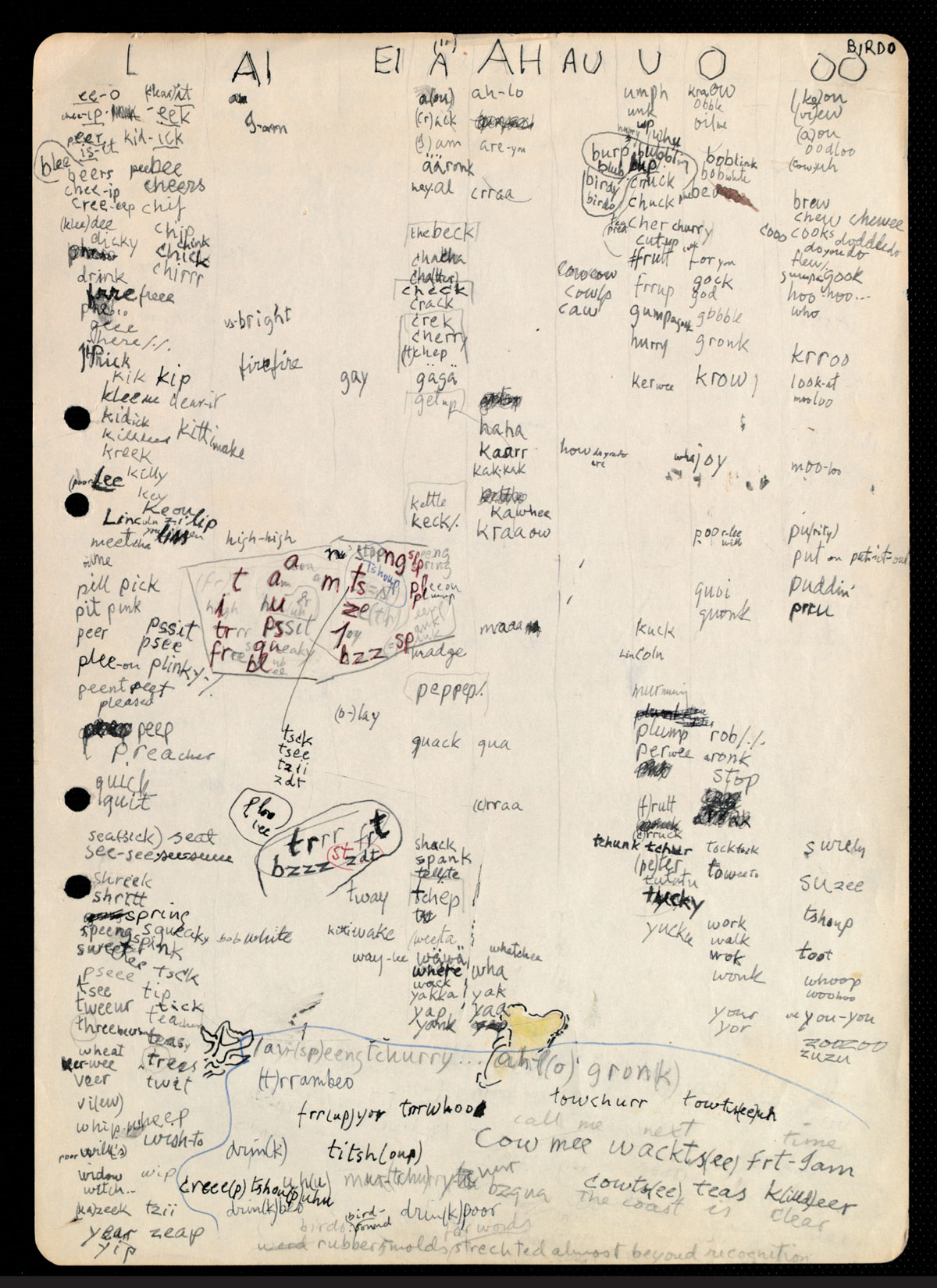

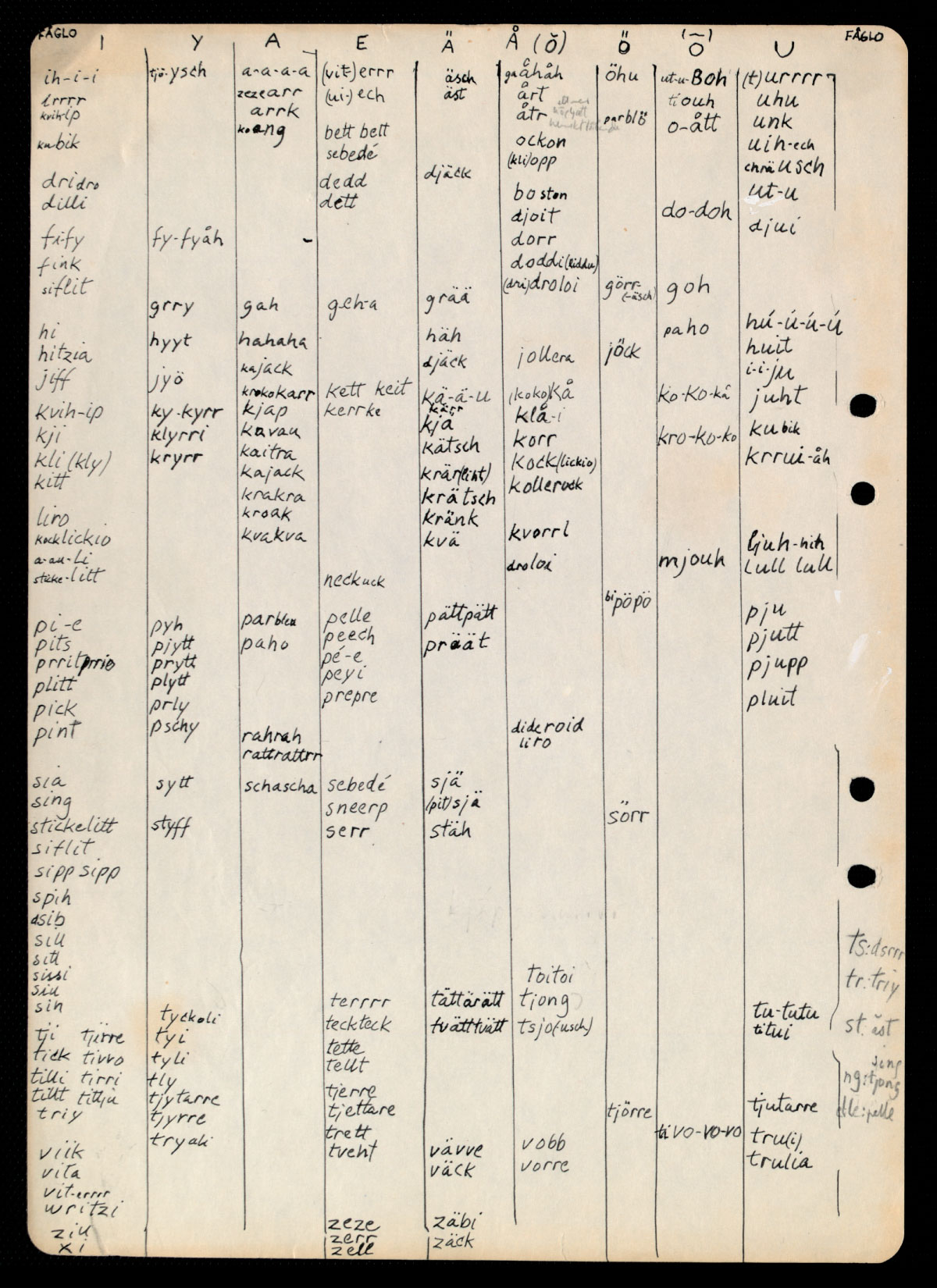

Birdo, Fåglo, Whammo

A. S. Bessa

“Monster languages” is the expression Swedish artist Öyvind Fahlström (1928–1976) used to refer to his experiments in creating new languages: “birdo,” based on American bird sounds; “fåglo,” based on Swedish bird sounds; and “whammo,” based on onomatopoeic expressions in comic books. Of the few works that Fahlström produced employing “monster languages,” the 1963 radio play Fåglar i Sverige [Birds in Sweden][1] is the most ambitious.

The first thing that might strike the listener about Fåglar i Sverige is how lovely it sounds. This is partly a result of its operatic structure, which allows the work to unravel an entire web of references. Opera played a significant role in the work of Fahlström, either because of its combination of words, music, and imagery, the use of dramatic conventions to address historical events, or simply because of its extravagant explorations of language. Its combination of language and music provided Fahlström with a highly complex organizing principle that allowed him to fully explore the perplexity of language and its conflicting elements. Fåglar i Sevrige mimics opera at the same time that it reflects on the genre and expands its vocabulary. The fact that Fahlström needed an organizing principle in order to elaborate his work is evident in the many essays that he wrote on art. It is most clearly outlined in his influential “Manifesto for Concrete Poetry”[2] (1953), the first attempt to adapt Pierre Schaeffer’s[3] ideas on musique concrète to the realm of poetry.

Although Fåglar i Sverige was performed by Fahlström in the radio studio with the aid of a sound technician, it still comprises several “voices.” These voices are mainly recordings (of Basil Rathbone, Jan Lindblad, and a sample from Puccini’s Suor Angelica) that complement Fahlström’s narration. They add color by contrasting with the flatness of Fahlström’s narrative and are thus the equivalent of arias, duets, and recitatives. While Fåglar i Sverige also makes two clear references to operas (Suor Angelica and Wagner’s Siegfried), it is impossible to read a coherent story into this work. The action jumps back and forth between places that are only suggested, and the characters, if we can accept them as such, are equally obscurely defined.

One gets the sense that in Fåglar i Sverige Fahlström grasped a concept too huge for him to communicate in an orderly way, that the syntax available to him was inadequate to address his subject, hence the recourse to a collage of sound. The principle of collage (splicing, sampling, quoting) will then become the very syntax of this work as well as part of its subject matter. Thus, everything in Fåglar i Sverige is borrowed from other sources.

Within this structure of collage in Fåglar i Sverige, there are hints of birds becoming machines, of machines as extensions of natural organisms, and, ultimately, of nature being superseded by technology. This mimicry becomes particularly disturbing during “The Raven” section due to the encoded meaning that Fahlström extracts from a specific group of words. This operation is twofold: In the first part Fahlström isolates a cluster of words from Edgar Allen Poe’s The Raven and translates it into one “whammo.” “Whammo,” like its sister “monster languages,” is basically the translation of each syllable of a word into its onomatopoeic simile. For instance the word “Re-mem-ber” becomes “ring-munch-brru(p).” In this process each word is then distorted and morphed into an entirely new word through the mere mimicry of its sound:

December

ember

floor

morrow

borrow

sorrow

Lenore

evermore

dringsmekbrru(p)

hm-brru(p)

f(e)h-oww

mmmrrrowroww

brr(p)rrowroww

zzzrrrowroww

kli(p)unghoww

wham-moo-oww

However, new words are not allowed to remain meaningless indefinitely. The next phase strives to restore their signification. Each new word is translated again, but this time into sounds recognized by the listener, with each word corresponding to a composite of two or three “natural” sounds, one for each syllable:

dringsmekbrru(p)

hm-brru(p)

f(e)h-oww

mmmrrrowroww

brr(p)rrowroww

zzzrrrowroww

kli(p)unghoww

wham-moo-oww

telephone-smacking-machine gun

humming-machine gun

snow shoveling-elephant

kissing-cat-elephant

machine gun-cat-elephant

snoring/sniffing-cat-elephant

bowling-groan-elephant

car crash-cow-elephant

Although Fåglar i Sverige delivers no specific message, it does reveal the operation of a system of messages that is hilarious and touching, half intuitive and half constructed, part natural and part historical. The lack of one unequivocal message in the piece does not imply that there is nothing in it for the listener. Once past the disorienting sheen of its initial impression, the listener is suddenly drawn into a sphere where language operates in an almost purely mechanical way—where repetition, sampling, and quoting engender misreading, decontextualizing, and hybridization. The general structure is primarily related to opera, but it also draws from radio dramatization in the tradition of Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds, and from documentary styles. From the start, Fahlström borrows studio technical devices such as “sound effects” and sampling to create atmosphere, and “real” information in the form of reportage. To complicate things further, he distorts these elements with complete disregard for the conventions of each style.

Fåglar i Sverige is a highly allegorical work that performs its narrative while linking our cultural past to our contemporaneous technological environment. The replacements and displacements performed on The Raven are carried out in order to illustrate the process through which words mutate. On the other hand, they also are the technique by which Fåglar i Sverige is constructed. In the double mirror that is Fåglar i Sverige, not even the image of the poet is left out of the frame. Hence Fahlström’s image emerges as “the operator,” camouflaged as a DJ in a studio of the Swedish Radio performing, sampling, cutting, splicing, scratching, mimicking in bird language the major works of other poets.

Samples of Fåglar i Sverige can be found here.

- A bilingual book-plus-CD edition of Fåglar i Sverige has recently been released in conjunction with excerpts from another radio-play, Den Helige Torsten Nilssen. See Teddy Hultberg, Öyvind Fahlström i etern—Manipulera världen / Öyvind Fahlström on the Air: Manipulating the World (Stockholm: Sveriges Radios Förlag & Fylkingen, 1999).

- An English translation of the “Manifesto for Concrete Poetry” is available at www.ubu.com/papers/fahlstrom01.html. The term concrete poetry was coined simultaneously and independently in the early 1950s by Eugen Gomringer in Switzerland and by Fahlström.

- Pierre Schaeffer (1910–1995) was the inventor of musique concrète, which he first performed publicly in 1950 in Paris.

A. S. Bessa is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn, New York. He is co-editor of poetry for fahlström.com and is also writing a book on concretism in the work of Öyvind Fahlström.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.