Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Severed Head

Any way you slice it, it’s not cut-and-dried

Mark Dery

Such scenarios were all in good, mean fun. When I was truly depressed, bummed by a life grown way too complicated in the midst of what was supposed to be the endless summer of a California boyhood, I’d daydream about decapitation. Twilight Zone comics, read by flashlight, under the covers, and the Aurora “Monster Scenes” model kits in the hobby shop window (among them a working, 1:15-scale guillotine whose plastic blade stood poised to decapitate the little victim that came with it) provided the raw material for imaginary beheadings whose symbolism was groaningly obvious: what better pain reliever for a loner who practically lived at the local library and whose grade-school head was already a wasp’s nest of hopes, dreams, fears, and insecurities, not to mention the fascinating factlets I was gleaning from all the books I was reading? Sometimes, it felt as if my skull was about to explode from the hyperbaric pressure of too much thinking.

My status as an only child compounded such problems. Solipsism is a singleton’s birthright, and I lived with a nonstop monologue inside my head—an ever-present voiceover that converted the world (the Not-Me) into the Me through an act of philosophical data-processing: the instant, reflexive categorization and critiquing of everything around me. It was alienating, this internal voice, turning me into a neurotic loner from a Bergman film who had somehow ended up in laid-back Southern California, harshing everyone’s buzz. In the SoCal of my youth, brooding existentialists in black turtlenecks were sentenced to re-education in Disneyland, The Happiest Place on Earth. To be sure, a Marcuse-ian critical distance was all that stood between me and the intellectual horrors of being mellowed to death, in the real-life Margaritaville of San Diego where I grew up. Nonetheless, there is such a thing as too much critical distance, and the little me inside my skull, the garrulous homunculus that insinuated its hyper-intellectual interpretations between me and everything I experienced, made me want to take a load off my shoulders with an axe, sometimes. If only I could lose my head, I thought, I’d be mindless—a happy camper at last.

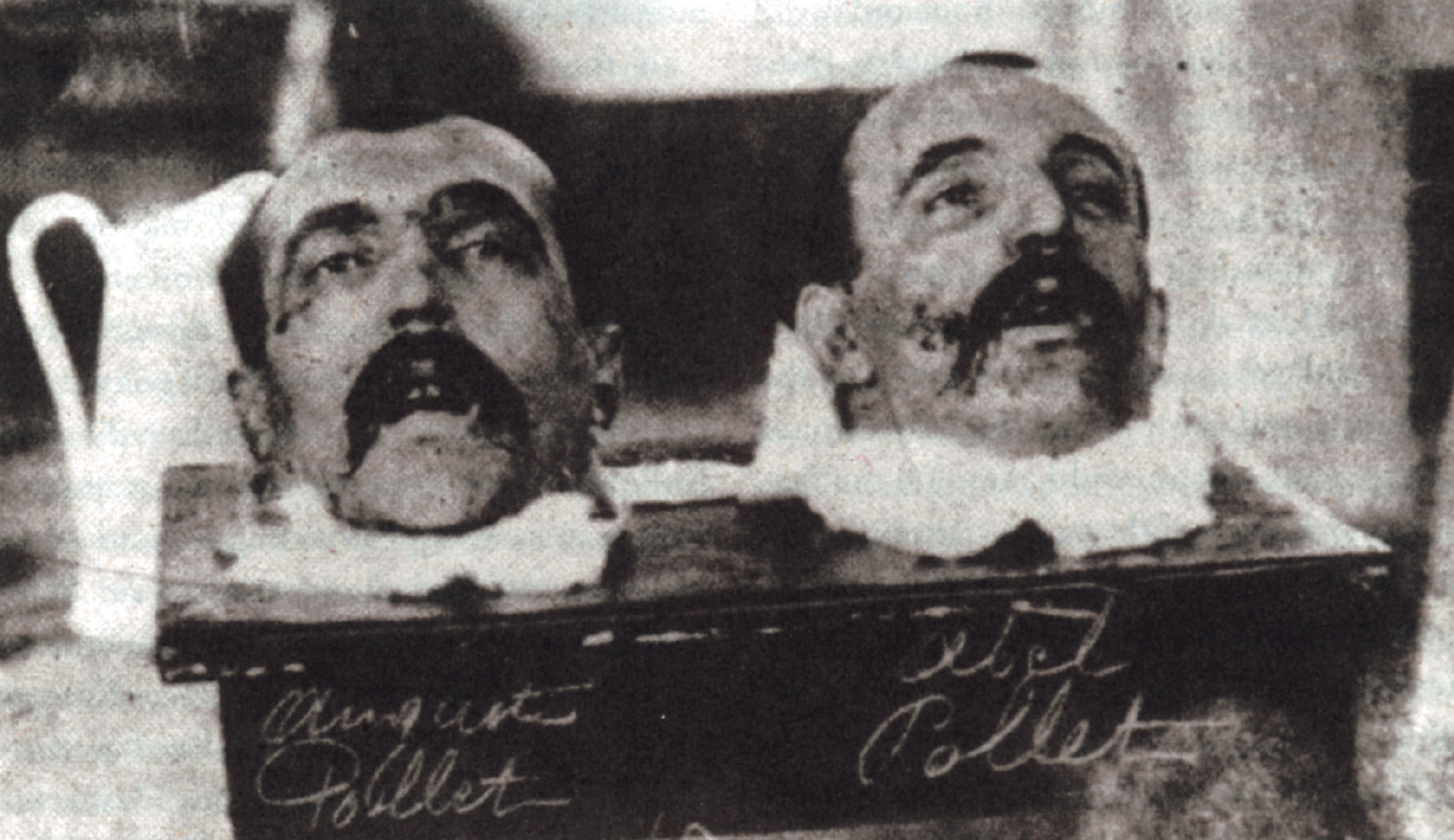

Typically, we see politicians, pundits, and the rest of the chattering class on TV, from the neck up, as talking heads—a term rich in symbolism. Listening to the just-shoot-me vacuities of bantering news anchors and Sunday morning pundits, one can’t help but wonder if they’re positive proof of the theory, propounded by some of the doctors who experimented on freshly guillotined heads in revolutionary France, that consciousness survives decapitation. The history of Dr. Guillotin’s ingenious machine abounds in gothic tales of severed heads that responded to the sound of their own names, a head transfused with the blood from a living dog (reportedly, its lips quivered and its eyelids fluttered), and the heads of rival members of the National Assembly which, when tossed into the same sack, sank their teeth into each other so tenaciously that they couldn’t be separated.[2] A Dr. Séguret claimed that heads whose open eyes were exposed to the sun “promptly closed, of their own accord, and with an aliveness that was both abrupt and startling,” while a head whose tongue was pricked with a lancet retracted it immediately, “the facial features [grimacing] as if in pain.”[3]

The evidence for the survival of awareness (as opposed to brain activity) after decapitation remains inconclusive. According to Dr. Ron Wright, a forensic pathologist and former chief medical examiner of Broward County Florida, “After your head is cut off by a guillotine, you have 13 seconds of consciousness (+/- 1 or 2). [...] The 13 seconds is the amount of high energy phosphates that the cytochromes in the brain have to keep going without new oxygen and glucose.”[4] Naturally, electrochemical activity is no guarantor of conscious thought, although as Wright notes, there are alleged instances of disembodied heads blinking in response to questions, “two for yes and one for no.”[5]

If bodiless heads can think, what about headless bodies? Mike the Headless Wonder Chicken springs immediately to mind. On September 10, 1945, Fruita, Colorado resident Lloyd Olsen sent—or attempted to send—Mike the way of all fryers with a well-aimed whack. Amazingly, the rooster survived his beheading; the next morning, Olsen discovered him pecking and preening (phantom head syndrome?), his reflex actions intact, thanks to a brainstem that had miraculously escaped the vorpal blade. Sustained by grain and water dripped into his exposed esophagus, Mike went on to sideshow fame. He lived for another 18 months before succumbing, at last, to decapitation-related complications.[6]

Historical flashbacks to a decapitated chicken who lives to strut another day, and to guillotined heads who seem to recognize the sound of their names, bring us full circle to meditations on TV’s talking heads. The symbolic resonances between severed heads (and the headless bodies they imply) and the ubiquitous image of the disembodied and seemingly brainless pol, pundit, or newsdroid, floating onscreen like a pickled head in a bell jar, reverberate in “Headless Reporter Continues Work,” a wire-service report from the future brought to you by the humor website futurefeedforward.com.[7]

Datelined 4 March 2005, the story is an account of an event that hasn’t happened yet, but will, according to the site’s revolutionary Temporal Networking Technologies. Apparently, 20/20 reporter John Stossel (widely reviled in progressive media circles as a flack for corporate interests) was—er, will be—decapitated while filming a skeptical look at alternative energy when a wind turbine whirs unexpectedly to life. Doctors act quickly, sealing off Stossel’s neck and leaving his “‘enteric nervous system’ or ‘gut brain’” in command of his mouth and mind.[8] In no time flat, he’s back in action and ready to kick tree-hugger butt, talking tough “through a vocoder linked to special contact microphones affixed to his neck”:

Responding angrily to questions about his decision to forego use of a prosthetic head, Stossel noted that he felt no embarrassment about being headless and that colleagues at ABC agreed that he has done some of his best work in years since the accident: “Do I wish it hadn’t happened? Sure. Am I any less of a reporter just because I haven’t got a head? No way.”[9]

The pay-per-view website The Fantasy Decapitation Channel (not to be confused with The Fantasy Hanging Channel) is all beheading, all the time. For $24.95 a month, subscribers can savor grand guignol photoplays such as “Lover’s Block” (“Two babes go naked on the block!”), “Annabelle’s Head on a Platter,” and “Double Decap Delight,” all of which feature women, nude but for panties, messily beheaded by swords, axes, and scarily convincing guillotines.[11] The executioners are usually men—though occasionally they’re goth babes in latex fetish gear—but the victims are always female.

In this weirdly chaste torture garden, a sort of soap-opera De Sade, the men are always clothed, and maintain a respectful distance from the female victim; male desire is displaced onto the falling blade, which penetrates her soft, virginal neck in a Freudian metaphor that’s as subtle as a bag of axes. Where most hetero-guy porn sites obsess over double-“D” cups, The Fantasy Decapitation Channel rejoices in double decaps; here, the climactic moment comes when a jet of gore geysers out of the neck stump of some sweet young thing—a necrophilic parody of ejaculation depicted with obsessive realism, thanks to the sleight-of-eye made possible by image-manipulating software.

In lustmord porn like the stories archived at Chez Marquis, death by decapitation is the ultimate erotic buzz; here, as in the autoerotic asphyxiations endlessly replayed in the novels of William S. Burroughs, death is precisely synched to the split second of orgasm. To the authors of such fantasies, it is an ecstatic agony, beautiful as the chance meeting, on a chopping block, of sex and death. In “A Rolling Head Gathers No Moss,” by the pseudonymous Marquis of Chez Marquis, the supermodel Kate Moss has “the best sex of her life on the guillotine where Madonna died.”[12] In the Marquis’s story, the death-blow and the “little death,” as the French call orgasm, come together in an emotional crescendo of exquisite pain:

His cock twitched inside me, ready to deposit its final load. I took a deep breath—my last—and pressed the button. The blade fell flawlessly, as I had known it would. It sliced through my neck like a hot knife through butter. There was no pain. The world tumbled, then righted itself as my head landed in the basket. My headless corpse reared up on the table, in the throes of an ecstasy, a passion so complete that it defies words. And as red faded quickly to black, the last thing I saw was my lover’s face, and on it a look of purest pleasure.[13]

Here, Marquis lives up to his namesake, who re-imagined murder as an erotic thrill beyond all others. To the Sadean imagination, power—power without limit, unbound by conscience—is the ultimate high. It extends the ego, godlike, to the edge of infinity, transforming everything within its sphere into the raw material of the lord and master’s pleasure. A casebook example of sadism, decap fantasies draw their voltage from the utter subjugation of the other, her (almost always her) reduction to a paraphilic object—a mute, manipulable toy on which the author of the fantasy can exhaust his desires. At its most extreme, this objectification refunctions the head—metonym for the human and repository of the psyche, of all that makes us unique, thinking beings—into a pocket vagina, as in the Chez Marquis story “Giving Head”:

I gasped as I fucked her dying, disembodied head. [...] To my astonishment I realized that I had gone all the way through her. The top four or five inches of my erection emerged from the bloody stump of her neck.

The antics of her headless body were comic, but also deeply erotic. Her hands reached up to feel around for a head that wasn’t there any more.[14]

“Comic” in the sense that the sight of the human reduced to a witless, herky-jerky mechanism is always comical, as Bergson famously argued in Laughter (1900); erotic in the sense that the willful mind reduced to the purely animal—a fuck puppet who lives to serve your every perverse whim—is erotic.

When she loses her head, the victim of “Giving Head” is reduced to a hot bod without all that troublesome thinking to get in the way, like the decapitated (but still spunky) Devil Girl who becomes Flakey Foont’s living sex doll in R. Crumb’s mind-bendingly misogynistic comic, “A Bitchin’ Bod.” As Mr. Natural, who performed the operation, tells a speechless Foont, “So I got to thinkin’ an’ figurin’—why not just get rid of th’ head? Th’ body is what we’re mainly interested in, right?”[15]

For straight men (and decap fantasies seem to be straight men’s meat), eroticized beheading, especially by guillotine, is a double-edged pleasure. Ostensibly a fever-dream vision of dominance and submission in which a Sadean male penetrates a powerless babe with his steely blade, decap snuff is haunted by the homoerotic gothic. The dark dreams of Marquis and others like him are shadowed by homophobic fears of the Queer Within: beheading is at once eroticized castration, ejaculation (with the spurting neck-stump as grotesque parody of the squirting penis), and sublimated frottage (decapitation rubs one phallic symbol, the blade, against another—the neck, which stands in for the penile shaft).

At the same time, the severed female head invokes what the feminist film critic Barbara Creed calls the monstrous feminine, that Gorgonian archetype whose stony glare and grinning gape mock the almighty phallus into shriveled impotence. The ur-text on this subject is of course Freud’s over-the-top essay, “Medusa’s Head” (1922), in which he asserts, “To decapitate = to castrate. The terror of Medusa is thus the terror of castration that is linked to the sight of something.”[16] For a young boy, that something is that unforgettable first glimpse of the awesome female pubes, most likely his mother’s, with their snaky tangle of hair. To Freud’s terrified little boy, mom’s you-know-what is at once a fearful wound where the penis used to be and a shaggy maw, waiting to gobble up his organ as well. Medusa’s serpentine locks are the severed members of her Bobbit-ized victims.

What would the Jewish father of psychoanalysis have made of Hitler, had he known that the Führer was fascinated by decapitation? The man who vowed that heads would “roll in the sand” when he came to power, and who once remarked that German justice should consist of “either acquittal or beheading,” wasted no time bringing the guillotine back from history’s prop room.[17] According to Daniel Gerould’s Guillotine: Its Legend and Lore, an estimated 16,500 enemies of the Reich were murdered with the machine.[18]

Tellingly, the Führer was “infatuated,” in the words of Hitler scholar Robert L. Waite, with the beheaded Medusa, she of the “piercing eyes that could render others impotent.”[19] Franz von Stuck’s gothic painting of the Gorgon cast an eerie spell on the Nazi leader—“Those eyes! Those are the eyes of my mother!,” he reportedly exclaimed, on seeing the painting for the first time—and a carving of the Medusa’s baleful head decorated the front of the massive desk he designed for his office in the Chancellery. Furthermore, Hitler was inordinately proud of his own penetrating gaze and often “practiced ’piercing stares’ in front of the mirror,” according to Waite. Freud theorized the “substitutive relation between the eye and the male member which is seen to exist in dreams and myths and phantasies,” and Waite, ever the Freudian, traces Hitler’s Medusa fixation to sublimated castration anxiety, inspired by an allegedly undescended testicle.[20] “In order to help master the anxiety engendered by the anatomical defect, disturbed monorchid boys favor symbolic substitutes for the missing testicle,” asserts Waite, who notes that such patients “may be excessively concerned about eyes.” Reportedly, Hitler exulted in staring people down. “In effect,” writes Waite, “he may have been saying to them and to himself, ‘See, I do have two powerful (potent) testicles, and I can penetrate and dominate others.’”[21] And if piercing eyes could serve as a potent surrogate for a missing testicle, might not bodiless heads represent the severed member—phallic talismans obsessively collected by a monorchid haunted by the unconscious fear that he was “half a man?” It’s a theory, anyway, as laughably hyperbolic yet satisfyingly neat in its narrative closure, as Freudian readings always are.

But Freud holds no patent on the psychosexual subtext of decapitation. As Daniel Gerould points out in Guillotine: Its Legend and Lore, “Severed male heads and decapitated bodies play a prominent role in the decadent art and literature of the late 19th century, particularly in the biblical stories of Judith and Salome. Flaubert, Huysmans, Laforgue, and Wilde in literature, and Moreau, Klimt, Beardsley, and Munch in painting are the best known of a whole host of male fin-de-siecle artists obsessed by visions of vengeful, headhunting, ‘demonic’ women.”[22] Think of “The Climax,” Beardsley’s drawing of Wilde’s lascivious Salome, pursing her lips to kiss the severed, still dripping head of John the Baptist.

Meanwhile, the gentle sex was hunting heads in actual fact. The huge crowds that flocked to public guillotinings in 19th century France included a significant number of women who, as one of the characters in Henri Monnier’s 1829 short story The Execution notes, reportedly found the spectacle more titillating than men did.[23] Nor was the arousal of female bloodlust in the presence of the National Razor, as the French called their decapitation machine, unique to the 19th century: In a note to his novel Justine (1791), de Sade observes that “whenever there is a public assassination ... almost always women are in the majority” because “they are more inclined to cruelty than we are,” a predilection the Divine Marquis attributes, curiously, to the fact that “they have a more delicate nervous system.”[24]

Fittingly, the guillotine itself was mythologized, in the mass imagination, as a man-eating Black Widow, yet another manifestation of the Romantic archetype of the femme fatale. Gendered feminine in French (“la guillotine”), the machine was referred to as Guillotin’s daughter, and soon acquired nicknames such as “Dame Guillotine” and “The Widow.” Her white wood not yet stained, a guillotine was known as a “virgin” until she had tasted her first blood. Taking one’s place on a virgin machine—lying flat on one’s belly on the plank known as the bascule, head in the pillory-like lunette that holds it in place so the blade can do its work—was called “mounting Mademoiselle.” After her ritual deflowering, a guillotine was painted red; lying on her was known as “mounting Madame.”[25] In the same spirit, the Scottish decapitation machine, the precursor of the guillotine, was called the Maiden. According to Regina Janes, a specialist in 18th century culture, “The last man to die by the Maiden, the earl of Argyle in 1685, declared ‘as he pressed his lips on the block, that it was the sweetest maiden he had ever kissed.’”[26]

I’m looking at the photographer Scott Lindgren’s portrait of a breathtakingly lifelike sculpture of a decapitated Chinese head, which appears in the 2000 calendar of the Mütter Museum at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Presented to the Museum by Dr. Charles D. Hart in 1896, it may be Japanese in origin, and is made of unknown materials, although X-rays have revealed that it has a wooden armature. “Its purpose is unknown,” the photo caption notes, “whether to serve as a substitute for a real trophy head, or as a stage prop.”[27]

For my purposes, the Mütter head will serve as an alas-poor-Yorick aid to contemplation, a disquieting muse. Studying its soulless eyes, brow knitted in pain; the braided pigtail looped around its neck-stump; the trickle of blood oozing from one nostril, and the weirdly labial folds of the horrific gash in one cheek (did the executioner miss on first try?), I think of the severed head as a signpost at the edge of the modern world, marking our border-crossing into precivilized times. Sad, battered, and bloody, the Chinese head in the Mütter calendar looks like the gruesome relic of a more barbarous age, like the infamous woodcut of Vlad the Impaler having dinner amid a forest of spears writhing with impaled victims or the eye-curdling 1905 photo, reproduced in The Tears of Eros by George Bataille, of the murderer tortured to death in the unspeakable Chinese punishment known as the “Hundred Pieces.”[28]

In fact, decapitation is still with us, perpetuated by totalitarian regimes, fanatical sects, lone psychopaths and anyone else in need of a particularly humiliating slap in his victim’s face, an indignity that heaps desecration on death. It’s especially popular among Islamist terrorists such as the Abu Sayyaf guerrillas in the Philippines or the Pakistani group that cut off Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl’s head after killing him. Beheading is voguish, too, in nations under Koranic law, such as Iraq and Saudi Arabia, where according to Amnesty International, the accused are routinely decapitated after confessions extorted under torture, for “apostasy, witchcraft, sexual offenses, and crimes involving both hard and soft drugs.”[29] In the age of biotech, nanotech, cloned sheep, and the cracking of the genomic code, there are corners of the world where the Reign of Terror never ended. Heads (often women’s) roll in the noonday sun, their blood lapped up by thirsty sand.

(Lest I be accused of stooping to Orientalist caricature in my evocations of Muslim cruelty, I’ll take time to point out the obvious, namely that the kinder, gentler slaughterbench of American capital punishment is hardly more humane in its methods, with the possible exception of lethal injection. Decapitation, Saudi-style, is unquestionably more gory, but it’s also swifter, and closer to a painless end, than our more civilized methods of strangulation by hanging, asphyxiation by gas, death by firing squad, and, most notoriously, being fried alive in the electric chair. Accounts of the botched 1997 electrocution of convicted killer Pedro Medina describe flames shooting out of Medina’s facemask and smoke that stank of burned flesh, making the Saudi sword seem like sweet relief by comparison.[30])

Staring at the anonymous Mütter head, I think, too, of decapitation as political protest, from Renaissance Florentines’ embrace of the Biblical story of Judith as a metaphor for their righteous resistance to Medici rule, to “Margaret on the Guillotine,” an anti-Thatcher tune on Morrissey’s 1988 record, Viva Hate (a politically incorrect fantasy, complete with guillotine-clang sound effect, that earned the pop star a visit from the police), to Paul Kelleher’s ritual decapitation, in 2002, of a statue of Lady Thatcher. Kelleher said he believed the ideology of conservatives like Thatcher was doing “irreparable damage” to the world in which his two-year-old son was growing up. “I haven’t really hurt anybody,” he said. “It’s just a statue, an idol we seem to be worshipping.”[31]

But somewhere behind the cloud of meanings conjured up by the severed head lies a severed head—a pathetic, flesh-and-blood being who experienced the mind/body split at its most cruelly literal. What must it feel like to be a thinking, feeling, seeing, hearing being one instant and, with the flash of a blade, a heap of dead meat the next? And how can we imagine the unimaginable—that 13-second eternity when your body twitches, headless, on the bascule and your head sits in the sawdust-strewn basket, staring skyward, still thinking, thinking of what? Do you squint into the glare of the sun before your consciousness flickers into nothingness? Do you wrinkle your nose when a fly walks across it? Does 13 seconds stretch into a frozen moment, as it does in the movies, time enough to rewind and fast-forward through a life? Does your severed head experience a sort of phantom limb—or, rather, ghost body—syndrome? Where are you when you lose your head?

In his gothic fantasia, Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head, the 19th-century Belgian romantic painter Antoine Weirtz puts our heads in the lunette and drops the blade:

A horrible noise is buzzing in his head.

This is the noise of the blade coming down.

The executed prisoner believes that he has been struck by lightning, not by the blade. Incredible! The head is here, under the scaffold, but it is convinced that it is still up above, a part of the body waiting all the while for the blow that must separate it from the trunk. ...

...The eyes of the condemned prisoner roll in their bloody sockets.

...They stare fixedly toward the sky, he thinks he sees the immense canopy of the sky tear in two and two parts draw apart like huge curtains. In the infinite depths behind, there appears a blazing furnace, where the stars seem engulfed and consumed forever.[32]

Here is where words wink out like dying stars, lost in the endless night of the unthinkable. Shorn of the organ that makes meaning, the decapitated never ask what a severed head means. Or, perhaps, by losing their heads, they find out at last, but cannot tell us. Their lips tremble, their eyelids flutter, two for yes and one for no, but 13 seconds is too brief an eternity to tell the living the meaning of life.

- In the age of Ashcroft, when as White House spokesman Ari Fleischer helpfully reminds us, “all Americans ... need to watch what they say,” cultural critics who wonder aloud how the president’s head would look in a basket are asking for an all-expenses-paid stay in a re-education camp or a midnight knock from the secret service. Thus this disclaimer: my remark that George W. Bush looks as if he deserves to lose his head is politically incorrect whimsy only, and is not intended as a threat to, nor as an incitement to violence against, any actual person, living, dead, or illegitimately enthroned by a jackleg judiciary.

- See Daniel Gerould, Guillotine: Its Legend and Lore (New York: Blast Books, 1992), pp. 54–56.

- Quoted in Daniel Gerould, Guillotine, p. 54.

- Quoted in Robert Wilde, “Does The Head of a Guillotined Individual Remain Briefly Alive?,” 2001, available at europeanhistory.about.com/library/bldyk10.htm?terms=Wright [link defunct—Eds.]. The Wright quote appears in full at www.urbanlegends.com/medical/decapitated%5Fhead%5Fblinking.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- Ibid.

- See “All About Mike,” at www.miketheheadlesschicken.org [link defunct—Eds.].

- “Headless Reporter Continues Work,” at www.futurefeedforward.com [link defunct—Eds.].

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Links listed at cuddlynecrobabes.com/promo2/home04.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- “Lover’s Block” at www.fantasy-decapitation-channel.com/Free%20Samples/ Oh%20yeah!/Loversblock.jpg; “Annabelle’s Head” at www.fantasy-decapitation-channel.com/Thumbs%2035.htm [links defunct—Eds.].

- Marquis, “A Rolling Head Gathers No Moss,” at www.scrye/com/~marquis/kate.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- Ibid.

- Marquis, “Giving Head.”

- R. Crumb, “A Bitchin’ Bod,” in The R. Crumb Coffee Table Art Book (Boston: Kitchen Sink Press / Little, Brown and Company, 1997), p. 233.

- Sigmund Freud. “Medusa’s Head” [1922], in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. & trans. James Strachey, vol. XVIII (London: The Hogarth Press, 1955), p. 273.

- John Toland, Adolf Hitler, Volume 1 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co.., 1976), p. 143.

- See Daniel Gerould, Guillotine, p. 240.

- Robert G. L. Waite, The Psychopathic God: Adolf Hitler (New York: Basic Books, 1977), p. 157.

- Sigmund Freud, “The ‘Uncanny,’” in On Creativity and the Unconscious (New York: Harper & Row, 1958), pp. 137–138. For more on the case of the missing testicle, see Robert G. L. Waite, The Psychopathic God, pp. 18–22.

- Robert G. L. Waite, The Psychopathic God, p. 157.

- Daniel Gerould, Guillotine, p. 182.

- Ibid., p. 99.

- Ibid., p. 183.

- Ibid., p. 182.

- Regina Janes, “Beheadings,” in Sarah Webster Goodwin and Elisabeth Bronfen, eds., Death and Representation (Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993), p. 255.

- “October,” in The Mütter Museum 2000 Calendar (Philadelphia: The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, 2000).

- Georges Bataille, The Tears of Eros (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1989), pp. 204–206.

- Norman Kempster, “Oil-Hungry U.S. Ignores Human Rights Abuses of Saudi Arabia,” The Los Angeles Times, 28 March 2000. Reprinted at www.commondreams.org/headlines/032800-01.htm [link defunct—Eds.].

- Susan Candiotti, “Botched Execution Prompts More Electric-Chair Scrutiny,” CNN.com, 26 March 1997. Available at www.cnn.com/US/9703/26/execution/index.html.

- Steven Morris, “Thatcher Accused Says: I’m No Criminal,” The Guardian, 5 July 2002. Available at www.guardian.co.uk/arts/news/story/0,11711,749923,00.html.

- Quoted in Gerould, Guillotine, pp. 109–111.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic. A frequent commentator

on new media, fringe thought, and unpopular culture, he is the editor of

Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture and the author of Escape Velocity:

Cyberculture at the End of the Century. His most recent book is the essay

collection The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.